A Network of Necessity Discovering Centuries-old Trails in a Swiss Canton

Words by Andrew Findlay | Photos by Kari Medig

A single uphill pedal strike could be disastrous. Focused minds make sharp decisions.

“If you fall here, you don’t dead,” says Christian Ammann in his blunt, grammatically unique English.

Coming from a stoic, Swiss-German farmer turned mountain bike guide, this amounts to encouragement. More than a vertical mile of white-knuckle descending below, the slate roofs of Stalden, Switzerland glitter in the sun next to the Matter Vispa river, swollen and coffee-colored with glacial melt driven by a record-breaking heatwave cooking Europe.

A few minutes earlier, and a half-dozen tight switchbacks above, we had left 80-something mountain guide Elmar Brigger sitting on the patio of Restaurant Jägerstube, his cliffside retirement project. With some prompting, he had tooted out a solo on the alpenhorn—he was rusty—before pouring a round of home-distilled apricot schnapps. It was delicious and made for a dose of well-timed liquid courage.

But this was no time for daydreaming. The trail here is narrow but smooth, bench cut by generations of foot and hoof traffic, where threading improbably through bands of quartzite was the only way for early trailblazers to navigate the terrain. Neat, parallel lines are etched in the compact gravel. Someone has recently raked the trail and clipped the trailside alpine rose bushes and grasses. The fastidious Swiss attention to detail knows no bounds. One look at a local farmer’s meticulous firewood stack and it’s obvious that only an inherently genetic predisposition for organization could produce it. To a non-Swiss eye, it’s a bit like sculptured perfection when much less would have sufficed.

When you travel with your mountain bike from British Columbia, a place that has built a mountain biking culture and brand all its own, it’s hard not to carry with you a certain smugness—you have already experienced the pinnacle; anything else would be a pretender to the throne. As a born-and-bred B.C. boy, I was about to be humbled.

Spend a few days in the Alps and you quickly realize the Swiss have refined the art of living in the vertical world like no others. They are master engineers, tunneling like groundhogs through mountains for road and rail. (“We are a nation of tunnellers,” a woman we met on the trail proudly stated). When conventional railway technology won’t suffice, the Swiss build cable-driven, and ingeniously counterweighted, funicular railways to ascend mountains. In 45 minutes, tourists can ride a train from Grindelwald to Jungfraujoch, a train station carved from the belly of the Jungfrau at more than 11,000 feet.

But long before the Swiss applied clever engineering solutions to transportation challenges, before their country became the adventure tourism destination that it is today, mule traders and farmers, driving cattle from valley bottom to summertime pastures, traveled through the mountains. Over the centuries, a network of paths emerged linking valley to pasture, village to village, and mountain to mountain. They were utilitarian routes tread by humans and horses. Naturally, hikers and mountaineers would eventually discover this organic trail system. Mountain bikers have been relatively late to the party. In fact, it took a while for this landlocked country of 8 million people to capitalize on and embrace its natural mountain biking resources, despite topography that lends itself to this sport.

Nancy Pellissier would know. She is part of the organizing team for the 2025 UCI World Championships which will be held in Valais, the third largest of Switzerland’s 26 cantons (like states), tucked up against France and Italy and home to legendary resorts such as Zermatt and Verbier. Pellissier grew up skiing Verbier and helping out at their family-run hotel. She remembers Chris Winter, of Whistler-based Big Mountain Rides, showing up at their hotel door years ago with his mountain bike and telling them that Valais was sitting on an empire of singletrack and didn’t even know it.

His words were few. When it came to riding, he lived by a simple creed that earned our immediate respect—ride asphalt and gravel roads only when all other options have been exhausted.

“We thought he was crazy,” Pellissier said. “We were like, ‘Why would you come here? Whistler is the place for mountain biking.’”

Times have changed. More than a dozen years later, Valais is preparing to be the first destination to host all seven mountain biking disciplines at the prestigious 2025 Worlds event. Organizers are expecting 150,000 spectators to descend on the region to watch downhill, pumptrack, marathon, cross-country, enduro, short track, and eMTB races at locations sprinkled throughout the area in an overt effort to showcase the goods.

To delve into this now-frenzied scene, I enlisted the help of Ammann, a man whose ancestors walked Valais’ trails as a way of life and livelihood and not in pursuit of thrills. Our plan, on paper, was to stick primarily to the “The 41,” a route marketed as a multi-day, off-road adventure traversing above the Rhône River and its tributary valleys while linking up some lesser-known mountain towns such as Saint-Luc, Leukerbad, Grimentz, and Grächen.

“We do the secret 41,” Ammann told us cryptically on day one as we pedaled up a service road on the verdant slopes of Crans Montana, naively wondering if we had accidentally signed on for an aerobic week of Euro gravel grinding.

Nonetheless, I remained hopeful given Ammann’s chosen biking attire—baggy shorts and shirt rather than the feared spandex and tight-fitting Transalp racing jersey.

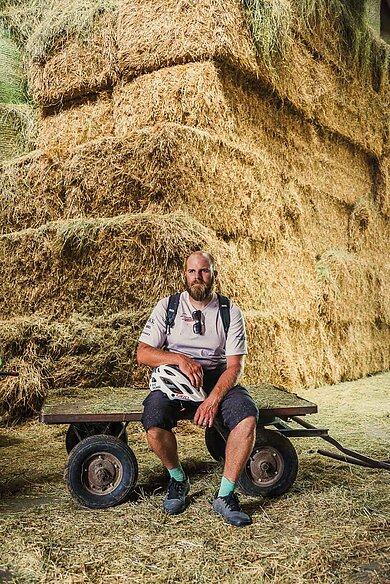

Besides a handshake, there were few formalities upon meeting Ammann. With a buzz cut and a triangular brown beard sporting a striking patch of blonde, he had the piercing gaze of a Viking on conquest and an upper body more suited to throwing hay bales than throwing down on two wheels. Despite his stout build, Ammann quickly proved to be a skillful shredder of steep, rocky, technical trails and a powerful climber. His words were few. When it came to riding, he lived by a simple creed that earned our immediate respect—ride asphalt and gravel roads only when all other options have been exhausted. This passion for mountain biking is the reason, to his father’s disappointment, he opted out of running the family farm in Leuk with his brother and instead launched Bike Saumer (Saumer means horseman in Swiss-German), a mountain bike guiding and instruction company.

By day five, our physiologies had adapted to the dizzying vertical of the Swiss Alps, but conversation with our reticent guide remained functional and to the point. Notably, Ammann had yet to ask a single question about our lives or riding in British Columbia.

After a glorious, brake-burner descent to Stalden, we cross a Medieval stone bridge spanning a gorge where the Matter and Saas valleys meet. An old man in faded jeans and suspenders waves us down. It’s oppressively hot. The UV burns. The man, leaning on his walking stick and sweating profusely in a long-sleeved plaid shirt, unleashes a stream of consciousness tirade for close to 10 minutes. Ammann nods his head patiently before finally interjecting, tactfully wrapping up a monologue without end.

“He said that the reason it’s so hot is because humans are shooting holes in the sky with rockets and letting the heat in,” Ammann says, shrugging off this unorthodox explanation for climate change.

We leave the man to his delusions, then board a gleaming gondola that departs exactly as scheduled at 12:22 p.m. It delivers us from the stifling heat of Stalden to the village of Gspon, home to Europe’s highest soccer pitch and some relatively fresh Alpine air. After a few hours of cross-country riding through forest and field, we arrive at Bergrestaurant Giw. A ham and cheese sandwich and, in a moment of weakness, a frothy pint of Feldschlösschen lager, is followed by a punishing, barf-inducing gravel road climb on a full stomach. We towel off after a rejuvenating dip in an alpine lake.

“The 41 goes that way, but this way is better,” Ammann says, nodding to a braided path climbing toward a mountain called Gibidum.

Switzerland can seem like a square and conservative country, a place where the trains and gondolas depart with impeccable punctuality and change happens in slow, tedious increments. Earlier in the week, we met a Swiss cop in the tiny village of Blatten who waited seven years for village officials to finally greenlight his artfully designed renovation of a centuries-old farmhouse. Though, when it comes to trail management, the Swiss have taken a surprisingly progressive approach. A commonly seen sign around Valais hints at the region’s share-the-trail ethos: a stick-person graphic of a hiker and biker with the words “Rücksicht, Respect, Rispetto.” Swiss-German, French, and Italian for “respect.”

So far in our travels, it appeared to be working. But sometimes there’s no substitute for local intel. One day, we pedaled through a collection of sturdy huts at Obere Feselalpe, a postcard-perfect, Alpine hamlet. Two old-timers in gumboots stood outside one of the small, slate-roofed chalets and frowned as we approached an electrified cattle gate, no doubt hoping we’d get zapped.

“Sali Zamu,” Ammann said.

Their frowns morphed into welcoming smiles. “If you say hello in the local dialect, then it's OK,” Ammann told us later. “If not, they might have told us to go far away.”

Food self-sufficiency is highly valued in Switzerland. The government provides many incentives to keep people raising cattle, milking cows, and making cheese. Farmers have clout, and getting on their bad side could make certain trails “verboten.” That’s why mountain biking diplomacy is always on Ammann’s mind.

Leaving The 41, it’s immediately obvious that we’re on a trail less traveled, one where user conflicts and run-ins with grumpy farmers are as unlikely as getting struck by lightning. A sudden change in the weather tips the odds. Storm clouds transform the calm blue sky into a shifting canvas of black and grey as we pedal and push to the top of Gibidum. The air is thick and humid. Wind gusts whistle through a futuristic cluster of cell towers and radio repeaters tethered like lightning rods to the exposed rocky summit. Without the cover of trees, it’s a vulnerable spot in a gathering electrical storm.

“That’s where we’re going,” Ammann says, gesturing toward a path that unfolds before us and snakes through a maze of sharp, tire-destroying rocks.

Scale is deceptive in these mountains. Our destination, Brig, looks like a miniature Lego city at our feet though it’s actually 5,000 vertical feet below in the valley of the Rhône River.

Forearms quiver in anticipation of another brake lever-squeezing descent. The energy of a pending storm propels us onward. Ammann leads. The trail is rocky and technical at first. Front wheel management is key. A wooden ramp cabled to the rock followed by a sharp right-hander is the only way to negotiate a cliff band. We all choose to walk, balancing risk with reward.

Another few hundred feet of descending and we’re on smooth, flowy dirt that weaves through meadows and larch trees. Mountain harebells, gentian, and other wildf lowers blossom in their mid-summer glory. The low-angled, benched terrain is short-lived. The steeps return with vengeance.

Switchbacks cut Zorro slashes through the thickening forest. Ammann effortlessly pivots around the corners, balancing on his front wheel while kicking the back around to complete his turns. It’s a mandatory skill that I’ll need to add to my Swiss Alps mountain biking toolkit. Without it, you walk.

Ammann pauses to shake out his pumped forearms, grips his back tire, then shakes his head.

“Too soft. I need more milk in my tire,” he says. Once a dairy farmer, always a dairy farmer. The scent of burning brake pads hangs in the air, the acrid aroma of mountain biking bliss. Switchbacks stack up in a blur of descending. An hour after dropping in from the stormy summit, we roll through a small pasture dappled in watery sunlight. Freshly milled timber is neatly stacked next to the rising stone walls of a new hut being built in the time-tested traditions of Swiss mountain architecture. Sunlight flickers through the liquid sky, then it goes ominously dark.

Fat raindrops begin to dimple the dry trail. Some moisture and extra tackiness would be welcome. A deluge wouldn’t be. Soon the trail contours toward the Gamsa River, cutting through an uninviting chasm. In this small country, one is never far from espresso, fondu, or schnapps, yet this particular valley feels unexpectedly wild and remote. An accident here would be a serious misstep. Only as I’m attempting to steer around a hairpin corner with another no-fall drop to the left does it occur to me that I forgot to buy emergency medical insurance for this trip. This unhelpful realization is immediately banished for fear of manifesting the worst.

A small concrete dam is our way across the Gamsa, more creek than river at this time of year. The water trickles playfully around massive, polished boulders, indicative of the volumes that flow during full flood. Ammann shoulders his bike for a steep hike on a crude trail that cuts through recently felled trees. My calves, already burning from days of descending and standing on clipless pedals, feel the pain. Once back in the forest the trail rejoins The 41, that route Ammann often references but seems to rarely ride. For the first time during the week, I savor the smooth, wide doubletrack—mountain biking’s version of a relaxation massage when compared to the rugged and raw singletrack of my dreams.

Rain intensifies. We debate whether to take shelter beneath a big fir tree but decide to pedal on. The dampness is a salve for faces blasted by a week of fierce alpine sun. Sticking to his mantra of singletrack all the time and at any cost, Ammann ducks left off of The 41 and onto more of the trail’s badass second cousin—steep, fast, techy, and, for most the part, locals only. Elevation drops quickly. Brakes screech in protest, metal on metal, rotors sizzling. In 10 minutes, we’re pedaling through the outskirts of Brig. The storm squall passes but the smell of fresh rain lingers as the cobblestone streets steam in the old town center.

The day’s efforts demand a simple remedy—burger, fries, beer—so we stop at Britannia Pub on the main square. It’s Friday night and it’s rowdy. Obnoxious cigarette smoke wafts over from an adjacent table of boisterous weekend revelers doing repeat shooter rounds. In the center of the square a group of young women performs a pop-up dance routine and then run through a fountain. I slouch deep into my chair, bagged, and sip a pale ale, daydreaming about the trails ridden while I recalled highlights in a week of many. As in art, the beauty of a trail is in the eye of the beholder. Back home in Canada, I’m accustomed to riding networks, isolated collections of purpose-built trails without any historical context or geographical relevance. Fun, but in an odd way, shallow—if it’s possible for a trail to take on human attributes.

Here in Valais, the network is the entire canton, a labyrinth of routes that served a functional purpose long before mountain bikers discovered them. And this gives them a raw and natural character that no machine can replicate. Throw in a gondola and an alpine bierstube exactly where you want them and the picture is complete.

I ask Ammann if he’d ever want to travel to Canada with his mountain bike.

“Maybe,” he says, taking a long pause to sip his beer. “But it’s so beautiful here.”

Perhaps this denotes an utter lack of curiosity about the wider world. More likely, it’s the sentiment of a guy perfectly at home in his own massive backyard mountain biking nirvana. I arrived a snob. I leave humbled. Perfection? Maybe not. But close to perfection is close enough.

![“Brett Rheeder’s front flip off the start drop at Crankworx in 2019 was sure impressive but also a lead up to a first-ever windshield wiper in competition,” said photographer Paris Gore. “Although Emil [Johansson] took the win, Brett was on a roll of a year and took the overall FMB World Championship win. I just remember at the time some of these tricks were still so new to competition—it was mind-blowing to witness.” Photo: Paris Gore | 2019](https://freehub.com/sites/freehub/files/styles/grid_teaser/public/articles/Decades_in_the_Making_Opener.jpg)