Welcome to Issue 14.2

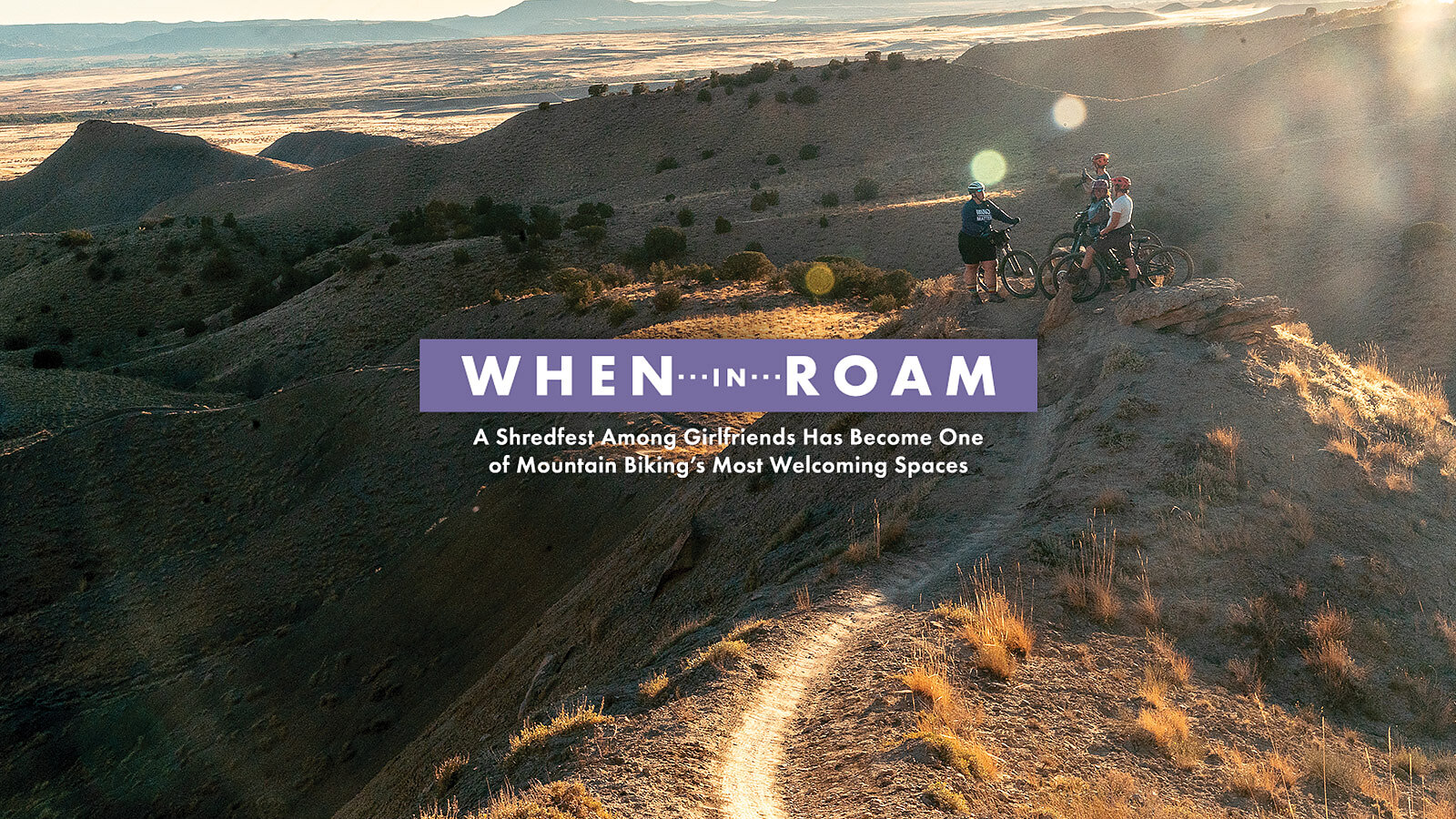

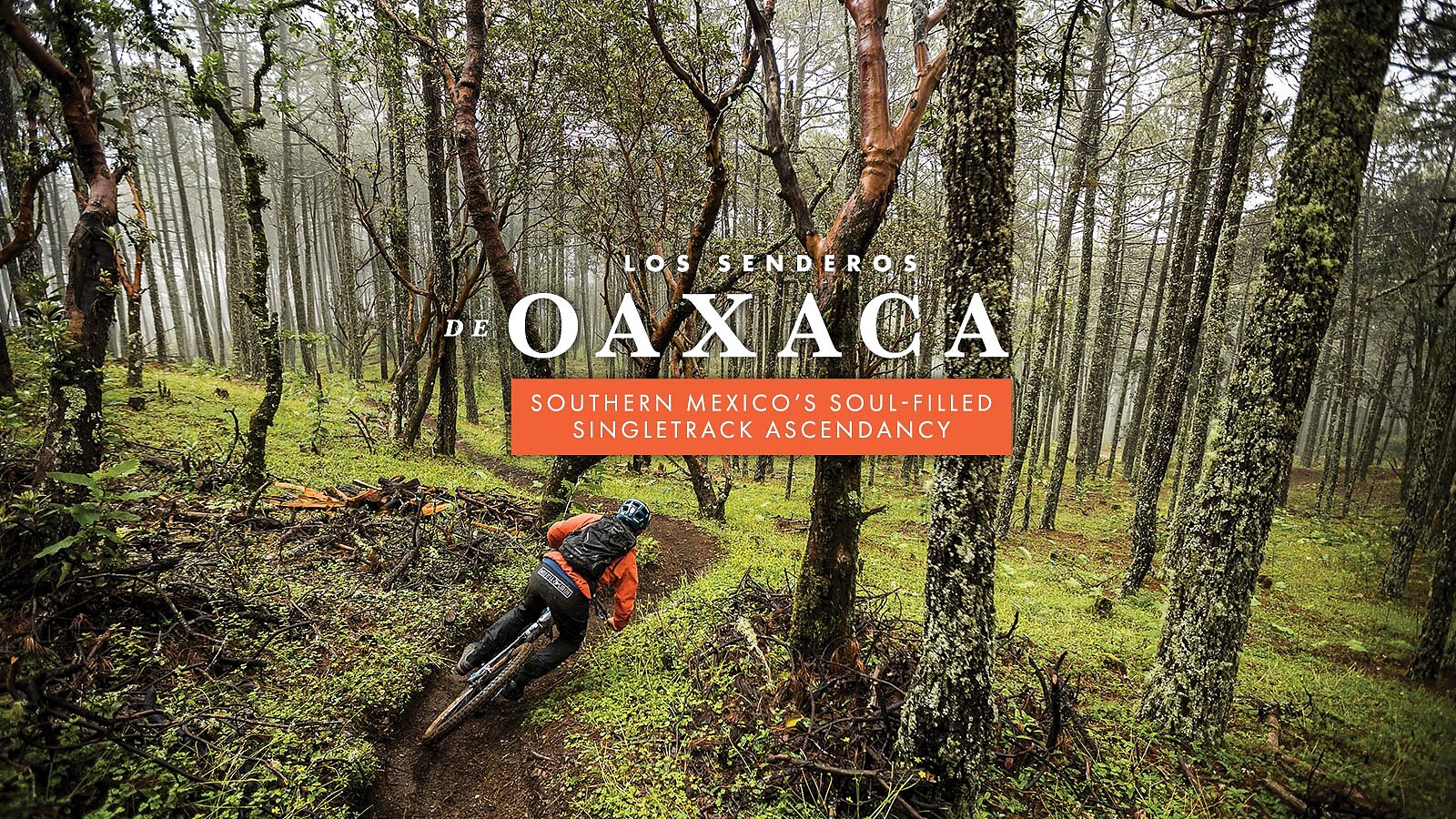

Since its inception 14 years ago, Freehub has been a magazine that revolves around community—both immediate and extended. Though every issue honors common threads that bind our ever-growing mountain bike community, this edition is dedicated to stories of cooperation, inclusion, and the shared passion for singletrack that unites our increasingly global culture. Our cover story chronicles the homegrown riding scene of Oaxaca, Mexico, where a devoted group of trailbuilders and guides have transformed ancient footpaths linking villages in the Sierra Madre de Oaxaca range into formidable networks that now attract riders from all over the world. We explore how the organizers of Roam Fest have set a new paradigm for radical acceptance in mountain biking with multi-day gatherings focused on inclusion and trust in an environment free from rivalry and posturing. These and many other stories help reveal what community truly means, and why the cohesiveness of mountain bike culture makes it unlike any other. Once you read through the pages of Issue 14.2, we’re sure you’ll agree.

Heidi Grande inched toward the commitment point of a pockmarked rock roll on Fruita, Colorado’s classic Horsethief Bench trail. It wasn’t the steepest or most technical part of the trail—and was much tamer than the Bench’s famously garbled entrance—but the feature was one of Grande’s mental blocks. As she let off her brakes and gave in to gravity, her eyes widened.

“Holy shit!” Grande said giddily as she cleaned the section for the first time. “I ride alone, so I never try it, but I’ve dreamed about it. Now, I know I can. I’m trying to get over my fear,” she said as her group gathered at the bottom of the feature.

“Following you was such a big help,” she said to her ride leader, a Roam Fest volunteer.

Grande, a recent Fruita transplant, had been too intimidated to seek out riding buddies in her new town. She signed up for Roam Fest in Fruita on a whim and ended up leaving after three days with newfound confidence and a couple of new phone numbers of other locals.

Words by Nicole Formosa | Photos by Anne Keller

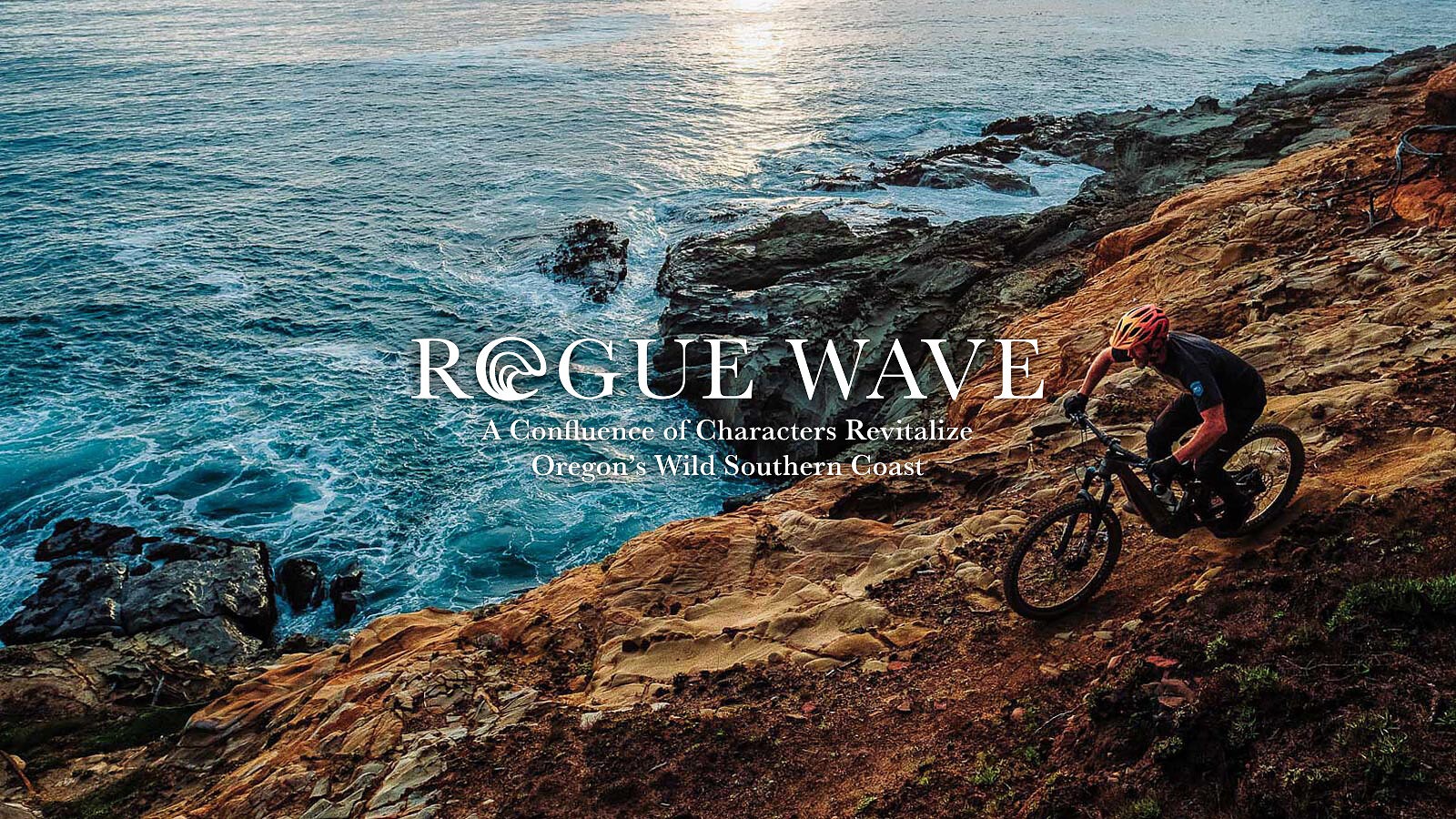

At The Crow’s Nest in the southern Oregon coastal town of Gold Beach, over a plate of fish tacos and under the gaze of mounted boars and framed Budweiser posters, Dave Lacey excitedly scrolls through digitized, historical topographical maps, buzzing at the backcountry mountain biking possibilities on nearby national forest land.

A man approaches Dave from a nearby table with a mischievous glint in his eye. He knows Dave. Here, in this community of 2,000 people, everyone knows each other.

“You know what the problem is with you, Dave Lacey?” the man says, his big beard bobbing over his hickory-and-high-viz shirt as he affably claps Dave on the shoulder. “You’re trying to make money off people coming here and having fun!”

Halfway down its 360-mile length, the orderly Oregon coastline begins to ripple and bend as several rivers pour into the Pacific Ocean. Locals call it the “Wild Rivers Coast,” with wild applying to more than just the terrain. This is still the Oregon of sasquatch sightings and secluded beaches, where forested summits crowd a little bit closer, and seaside cliffs tower a little bit higher than areas farther north.

Words and Photos by Aaron Theisen

An eerie calm pervades the brisk morning air as a steady patter of light rain mesmerizes a small group of riders huddled underneath a towering cluster of ferns. A dense fog cloaks the forest, silhouetting the gnarled branches of lichen-encrusted oaks against a hazy sea of grey. Mirroring the texture of the trees, a dark-brown ribbon of singletrack winds through clumps of bright-green moss, bisecting the forest floor in harmony with its natural contours.

Suddenly the stillness is ruptured by the vibrations of tires rolling over roots and rocks, punctuated by the reverberating thuds of wheels pounding into deep beds of loam. The riders peer up the hillside in anticipation as a lone figure emerges from the mist and slashes a sharp lefthand turn, sending a plume of soil soaring several feet above the berm’s wounded lip.

“Woo-hoo-hoo!” the figure shouts as he thunders past the group, followed closely by a second rider, answering his exclamations in the universal language of mountain bikers enraptured by weightless motion.

Words by Brice Minnigh | Photos by Riley Seebeck

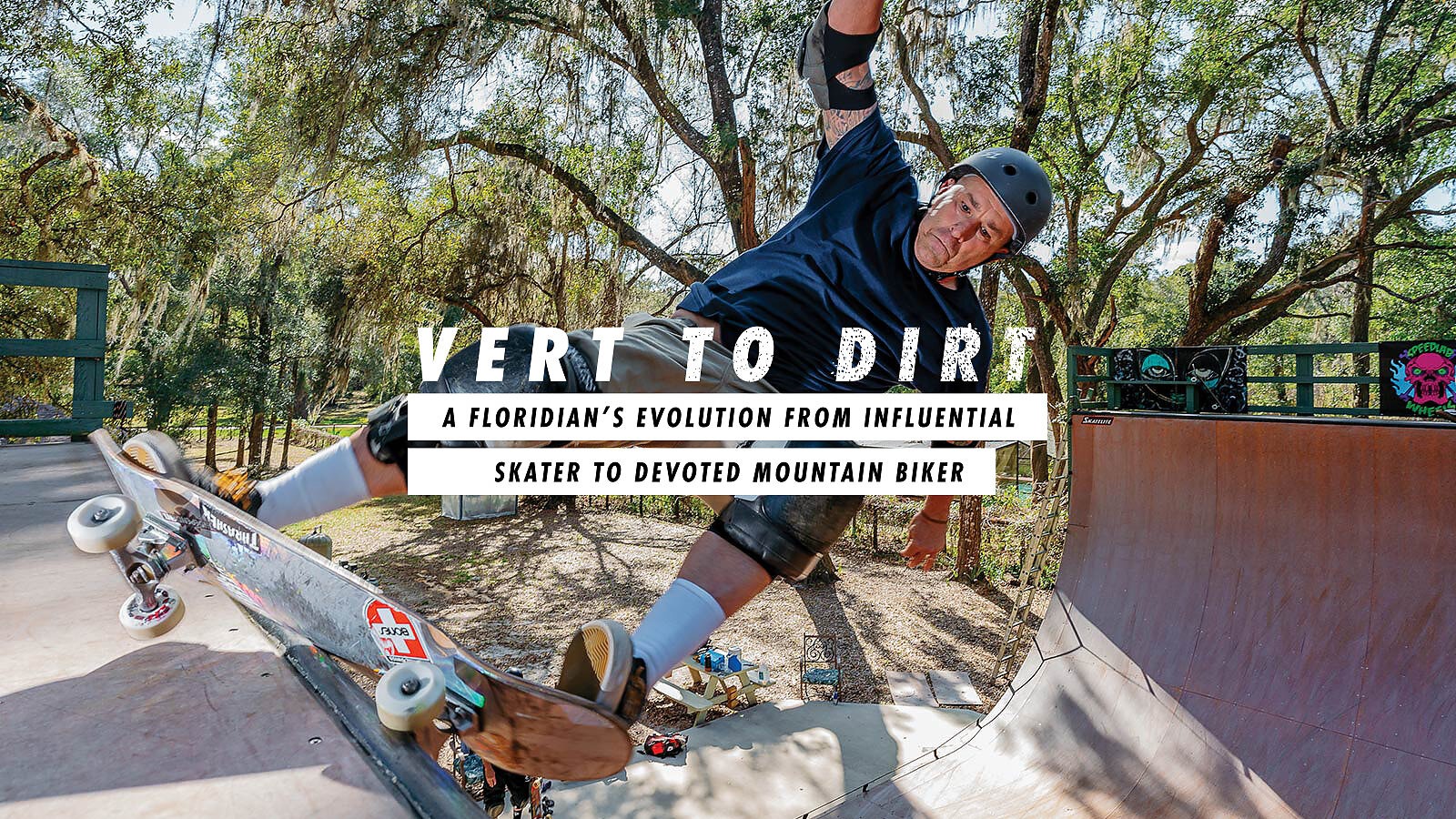

In Pete Thompson’s photography book, ‘93 til, which documents skateboarding through the 1990s, a quote from Tony Hawk appears alongside a black and white image of a man serenely floating on his back in a pool.

“The guy who was really revolutionary to me in the ‘90s was Mike Frazier,” the Hawk quote reads. “People have no idea about the difficulty, the creativity and the boundaries he was breaking, mainly because very few people were appreciating vert.”

For more than 30 years, Frazier reigned as a top professional vert skater. Today, at 50 years old, he still cheats gravity on a skateboard, though, on most days he can be found logging airtime through a different method: mountain biking at Alafia River State Park in central Florida.

He charges gaps and jumps at Alafia with the same aggression and determination that he displays on the walls of 13-foot ramps. Frazier only knows an “all or nothing” approach.

“I’ve done all of the other board sports,” Frazier said. “Nothing has felt as close to skating as being on a mountain bike.”

Words and Photos by Brett Rothmeyer

Above town, the rocky trails roll fast and smooth. They’re steep in places but always manageable. Riding here can be unforgiving; singletrack this far north is naturally demanding, with huge variations over short distances.

But during summer, when sunset and sunrise meld together into one monthslong stretch of light, when distant, puffy cumulus clouds provide the only contrast to an otherwise bluebird sky, when evenings spent chasing friends down singletrack spill well past 10 p.m., Åre is magisk.

Words by Mattias Fredriksson

I hate group rides. Just the thought of them fills me with anxiety and nervous energy. I don’t want to spend my ride chasing someone faster than me and, conversely, I’d rather not wait on people either. Selfishly, I want to go where I want to go at my own speed, whatever speed that may be on that particular day.

The thought of a swarm of strangers in a conga line on some random trail fills me with dread, and the inevitable parking lot posturing and competitiveness just isn’t my scene. It’s the antithesis of why I ride bikes. It isn’t necessarily a bad thing, it’s just not my thing.

Words by Chris Reichel | Illustration by Cierra Coppock

After more than a decade of notoriety for being one of the world’s most demanding sufferfests, the Crankworx Whistler enduro race will be going back to its roots this year as the Canadian Open Enduro— the same as its stunning debut in 2013, when five grueling stages pushed the world’s top racers to their outer limits.

At that time, North American enduro racing was still in its infancy. The moto-inspired race format, born in southern Europe and meant by its originators to replicate the everyday experience of mountain bikers chasing their friends down their favorite descents, had captured the world’s imagination. But while enduro’s action-packed nature and lively atmosphere was appealing to many, race directors and course designers outside of Europe were still trying to wrap their heads around the logistics for such massive endeavors.

Photos by Anthony Smith

It was October 1992 in western Pennsylvania, and autumn was in the air—brisk temperatures, leaves sporting hues of yellow, orange, and red, and the Pittsburgh Steelers getting walloped every weekend. October also signified the annual running of God’s Country Classic, a 30-mile race out in the middle of, well, you know.

Seeing as though I was only 15 years old, my parents wouldn’t let me drive the family truckster—a green Ford Explorer wagon with wood paneling—200 miles from Pittsburgh to north-central Pennsylvania by myself. So, my dad Klaus and I made the five-hour trip together, a terrific father-son bonding opportunity.

To make the 10 a.m. start, we left the house at 4 a.m. My dad—who preferred watching the Steelers get pummeled by every team in the National Football League over attending one of my bike races—bitched and moaned the entire drive. The thermos coffee was too cold. The family truckster was out of alignment. He couldn’t see out the back window because of my stupid bike. Where’s the goddamn road map? Just where the hell were we? The complaints went on and on, but his constant bellyaching was drowned out by the comparatively relaxing voice of Kurt Cobain serenading me on my Walkman portable CD player.

Words by Kurt Gensheimer | Photos by Victor Brousseaud