A Southwest Cycle Yeti Roots and New Endeavors with John Parker and Chris Herting

Words by Ben Gavelda

It’s a drizzly gray October morning in Durango, Colorado as I walk down the slick concrete sidewalk of Main Street.

From the looks of things, the area’s prized high-country riding season will now be abruptly cut short as the moisture pours out of the sky, piling high in the mountains.

I make my way into the Durango Diner, a greasy white-bread staple slipped into a sliver of downtown acreage. John Parker, a grandfather of mountain biking, wanted to meet here to tell his story. He’s easy to spot, a bear of a man with thick-rimmed glasses, knuckle tattoos and a flat-billed hat.

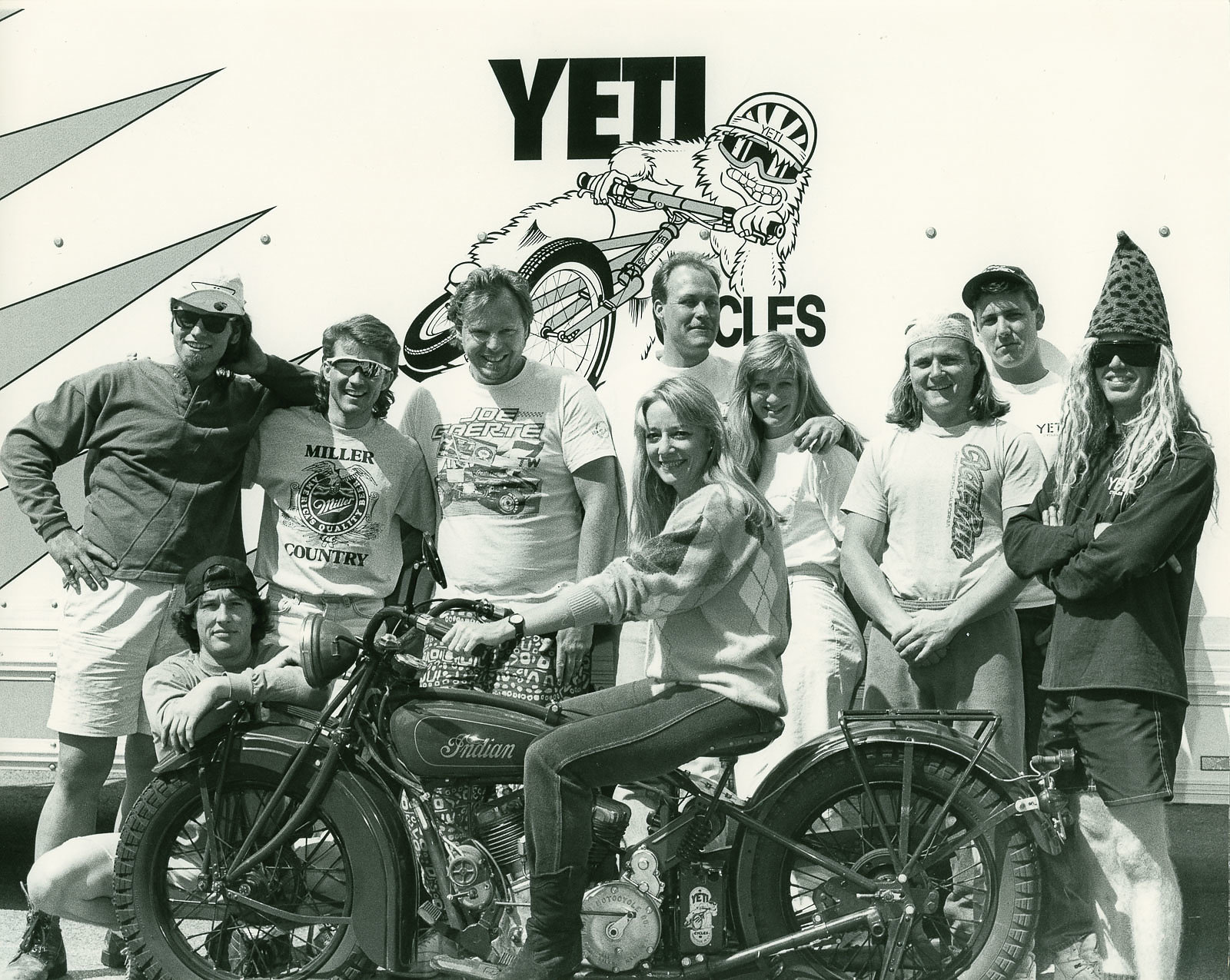

The diner is familiar ground for the 66-year-old Mountain Bike Hall of Fame inductee and warden of the sport. On the wall is a photo of one of his old Indian motorcycles—and one of him, actually, past the worn-out John Wayne painting and Native American art. The group photo he’s in reads “Yeti Ranch, Durango, Colorado, Christmas of ’93” and was shot in black and white, everyone dressed in cowboy attire, some on old bikes, some on old motorcycles, some standing.

Our meal is not of the quality he remembers, save for the green chile sauce. A lot has changed in Durango since its fat tired heyday in the late ’80s and early ’90s, a time when John and friends were running Yeti Cycles here. John is back, two decades later, with a new project called Underground Bikes. Within these foggy windows, over eggs and hashbrowns and watered-down coffee, Parker spills about mountain biking’s past and the path that’s led him back to the Southwest.

Yeti began in borrowed shop space in Southern California with integral fabricators and mountain biking visionaries Chris Herting and Frank “The Welder” Wadleton. The idea of moving the business to a remote locale like Durango didn’t make sense, but the place did, with its loads of singletrack, claims of hosting the World Championships, and status as the home base of numerous pros such as Ned Overend and John Tomac. In this nook of the rugged San Juan Mountains beat an early pulse of mountain biking.

Known for its aggressive and stout builds, Yeti exploded during the late ’80s in California and early ’90s in Colorado. But its rapid growth eventually sent John, Chris and Frank down different paths, leaving them not on the best of terms.

“I did not have a normal childhood, to say the very least,” John begins. “I grew up in a little place called Pacific Ocean Park, between Santa Monica and Venice. My biggest freedom was the bicycle. On a skateboard, I could ride up to the Santa Monica pier or to Culver City and that was my limit. But on a bicycle, I could go anywhere. At some point my mom remarried to a really bad guy and things got very violent. I was getting beat by this guy daily. I was the oldest, so of course he focused all his ire on me. I knew I had to get out of there, so I started running away. By the time I was 12, I’d been arrested twice for stealing cars and got caught smoking pot and off to reform school I went.”

With little interest in returning home, John stayed in juvenile programs and passed through various host families’ homes. The greatest things he learned while at Boys Republic in Chino Hills were honor, respect and how to weld.

In one of his host homes, the father was into motorcycle racing and turned John onto it. As soon as he turned 18 and left the program, all he wanted to do was race motorcycles. He started riding and racing and funded it with a job as a fabricator in the motion- picture industry. Through racing he met a bicycle genius by the name of “Bicycle” Bob Wilson.

“Not only was Bob involved in bicycles and all this,” John says, “but I met him at Ascot Park, where he would come into the pits after the races and write down in his book what racers he liked. He wouldn’t talk to you, he’d come up and grab three spokes on your wheel. And if he liked the tension, he’d just leave you alone. But if he didn’t, he’d leave his business card between the spokes.”

The two quickly became friends. Bob worked as the team mechanic at SE Racing, a BMX company, and later started his own brand. John got involved in Bob’s new endeavor and often stopped by during his commute home to weld some frames.

“Bob was a frickin’ bicycle genius,” John says. “Head angles, wheelbase, all this stuff came natural to him. And I’ll be honest, it didn’t come natural to me—I had to learn this stuff .”

Then two car accidents diverted their lives. One involved Bicycle Bob and his past offenses, which landed him in the slammer. John, who was by then into racing cars, suffered a horrible crash in Arizona. After paying medical bills, John was thin on money, but he had a 1928 Indian motorcycle. He sold it for five grand and bought Bob out of his bike business as he was leaving to do his time.

“I remember going to make the first couple of bicycles and needed some Campagnolo track dropouts,” John says. “I called Campagnolo and Richard Storino goes, ‘Hey dude, I have a warehouse full of those things, but be sure to bring a check for $150 because the last time Bob was here he slapped me with some bad paper.’ I realized that this was going to start happening all over town.”

That’s when John decided to change the name of the brand to Yeti so he didn’t have to pay Bob’s past debts. The inspiration for the name came from a “yeti” sleeping bag John had recently bought, and the early ice axe logo stemmed from his interest in mountaineering in the Southern Sierra range.

As John’s bike-building progressed, he met Chris Herting and Frank Wadleton, who both shared his passion for fabricating bikes. The special eff ects-coordinator on one of John’s jobs was Herting’s uncle, Harry Cavanaugh. Coincidentally, the Cavanaughs were from Durango and had helped build Colorado’s million-dollar highway (which stretches from Durango to Ridgeway) in the early 1900s. The three quickly took to creating mountain bikes for the newly evolving culture and sport happening in outposts like Marin County, Crested Butte, Laguna Beach and the hills around Los Angeles.

“From there it was a blur, it all started happening,” John says. “You know, all my life I’ve attracted artists and eccentric people. And here is this offshoot of bicycling that’s nothing but eccentric people. My people. And the attraction was huge and therefore I jumped in with both feet.”

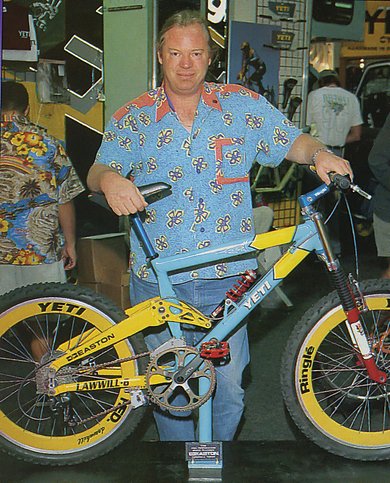

What made the bikes and the brand stand out was their privateering approach—a racing term that meant no factory support, no sponsors. The group turned that idea into a bike, creating fast, dependable rigs that could be raced season after season. Tough frames, computer-aided design, modern geometry and clean cable routing put models like the F.R.O., A.R.C. and Ultimate on podiums and wish lists.

If Parker was the face of Yeti, it was Chris who made the magic. He developed the prototypes, race bikes and ran the R&D shop during Yeti’s heyday. He’d never admit it, but this tall, quiet engineer, welder, tinkerer and bike visionary is arguably the most eligible candidate for the Mountain Bike Hall of Fame given all of his contributions to design.

“My dad had a kind of a metal fab shop in our garage, so we’d always drag home old bikes and cut them apart and make stuff for ourselves,” Chris says. “I was always tall, so I could never fit on anything, so the first bike I ever made was a BMX bike that was big enough for me.”

Then there was the Swiss cheese bike, where an adolescent Chris simply drilled lots of holes in all the tubing for style points or less weight—who knows.

Chris and his brother Eric grew from riding BMX around town to the Angeles Crest, where their dad Jim would shuttle them in the family van and let them rip down. Soon they were riding in Victor Vincente outlaw races like the Reseda to the Sea and exploring the newly growing sport of mountain biking. When he was a teenager, Chris began working at a bike shop that had a mill and some fabricating equipment.

“I started my American Iron Company back then out of the back of the bike shop,” Chris says. “I got into road racing, too, and began showing up at the races with my American Iron bikes and started selling bikes from that. Then I started doing mountain bikes just through word of mouth.”

Soon Chris and Eric got their own space, a converted bar, that became the first real American Iron shop. Then Frank Wadleton came into the mix. Frank had been riding bikes to work with Chris’ dad and soon started hanging out at the shop. Frank was a super-talented TIG welder, which was just what they needed. Word spread to Parker, again through Herting’s dad, and the group combined forces.

“Parker got ahold of me and I met with him and then started building the Yetis around ’85,” Chris says. “I would do the coping, fit up and everything, and Frank would weld them. The timing was perfect for mountain bikes and Parker was a good PR guy.” Although Yeti took center stage, Herting kept the American Iron side project all the while, eventually changing the name to 3D Racing.

By the mid-1980s, the crew was visiting Durango for a NORBA race when a chance encounter altered their path. Will Williams, president of the La Plata Economic Redevelopment Council, bumped into Parker at the race and it all transpired from there.

“After Yeti got out of the box and got big it was never going to go back into the box. By the time Schwinn offered to buy it, I was going through a divorce and it was time for me to cut out because instead of me building bicycles and running a race team, I became more of an animal trainer."—John Parker

“When Tomac moved to Durango,” Chris says, “Parker started thinking we had to move to Durango, like it’s the future of mountain biking and the company. I thought, ‘Well, yeah, if you’re a racer or something,’ but we were trying to run a business. I was real negative about moving; I was trying to be realistic. Parker had money through his wife’s family, but what else was I going to do if we didn’t have a sustainable business? Back then there was no industry in this town. It was nothing. If you weren’t a cowboy, you weren’t doing anything.”

The fact that Yeti paid American wages, had medical benefits for its workers, and was shipping internationally was attractive to the small mining/cowboy/ tourist town that was trying to establish a more sustainable economy. After that meeting, the council offered enough financial incentive for Yeti to move to Durango.

“I fell in love with it eventually,” Chris says. “The fact that I could go riding in any direction and have an awesome ride, I take it for granted. All I need is one trip back to Cali to realize how shitty it is there and how great it is here.”

Logistics were tough in this remote area and the first winter sent many of the transplanted workers back home. But the brand fed off the trails and community. Soon it was making bikes behind the scenes for Swatch Watches, Barracuda, Head, Schwinn, and prototypes for numerous other brands. Legendary riders Julie Furtado, John Tomac, Missy Giove, Myles Rockewell and Jimmy Deaton were riding for the brand.

“After Yeti got out of the box and got big it was never going to go back into the box,” John says. “By the time Schwinn offered to buy it, I was going through a divorce and it was time for me to cut out because instead of me building bicycles and running a race team, I became more of an animal trainer. I had my good dogs winning races and I had my anarchist bad dogs writing shit on bathroom walls. It was not what I signed up for.”

When Schwinn bought the company in 1995, John headed back to show business in California. Frank continued making bikes in Arizona and New York. Chris never left, and he’s been in the same house ever since, crafting custom mountain bikes for 3D Racing from his garage shop.

It’s a clear, cool, late October afternoon a few weeks later as I wind through country dirt roads east of Durango. A few vintage pickup trucks giveaway the location as I pull into Chris’ spread. He welcomes me into his small brown shop, a Smithsonian of bicycle history and innovation stuffed into a two-car garage. The place is plastered with memorabilia covering the life span of mountain biking itself. Signed posters of Brian Lopes, some of the earliest Yeti frames and a smorgasbord of bike parts cling to the walls.

There’s a mill, sand-blasting unit, various welders, a powder-coating oven and every tool under the sun crammed in here. It’s the office of a pure mountain biking mad scientist. This is home and it always kind of has been for Herting, whose life and livelihood have revolved around bikes and metal work.

Chris and I head out for a ride in town as the season is coming to a close. He brings a 3D Racing double top tube hardtail creation. For a man in his late 50s he utterly devours the uphill of Telegraph Trail, a classic lung-buster of a climb. He talks of the days when he would ride his dirt bike around the backside before the land was developed.

We peel off the mountain as the light fades fast, laughing about classic turns and rolls in the trail. We hurriedly snap photos and rip into the dark. The trail back to the parking lot winds up the La Plata River, across from the industrial part of town, back where a small-yet-international bike brand once stirred.

Many years have passed and the details may be messy, but the craft of bike building lives on in Durango as 3D Racing, Underground Bikes and other small outfits continue to create, test and relish fat-tired goods. It might be small, quaint and remote, but the cycling community pushes on.