The Condor Flies Alone Rick Hunter Lives by His Own Rules

Words and Photos by Brian Vernor

I’m sitting in the Bonny Doon, California, home of Rick Hunter, the reclusive—some would say reluctant—custom bicycle builder.

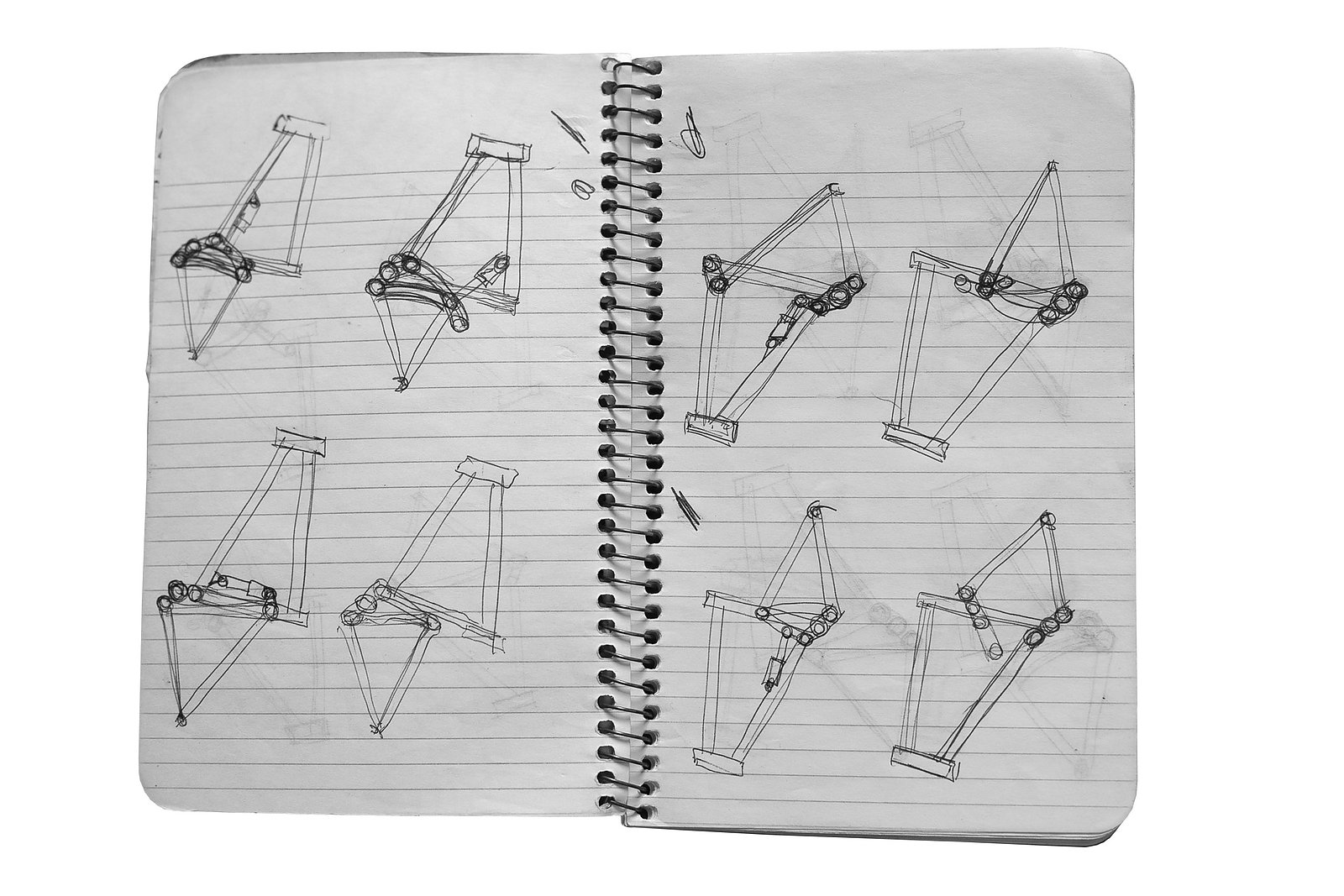

At my request, Hunter has pulled out a bunch of old personal and brand-related stuff for me to look through. His eight person dining table is covered with archival bits: concept drawings, to-do lists from more than a decade ago, race numbers, those post-race photos stamped with a copyright we’d receive in the mail with offers to buy finished prints, and no shortage of old magazines, now long out of print.

It’s been 20 years since British mountain bike journalist Chipps Chippendale’s The Outcast singlespeed fanzine was printed, with a cover blurb reading, “The untrendy end of the bicycle world… .” Hunter picks up the zine, which contains, unlikely though it seems to me, a fictional story he wrote called “The Rider.” He agrees to let me record him reading the short story, and we kill the sound from the scratchy vinyl of 1980s skate-punk band Jodie Foster’s Army that’s been blaring in the living room so I can get a clean recording.

“The Rider” paints a portrait of a lone man making his way from a liquor store to his home in a dilapidated boat. It wades through his narcotic dreams of a time before all went bad here on Earth and continues to the present time, when “off world colonies” float above the clouds. The Rider is desperate to find an old friend who might not be a friend anymore; it’s hard to really know, but the search is an important part of the story. The world inhabited by The Rider is grim, but he seems at home there—a competent survivor in a world of limited resources.

I can’t overlook a parallel to the experience Hunter has had as a working man, alone in his shop, mitering, machining and brazing raw material into the shape of a bicycle. There’s weight to the story, and in spending time with Hunter at some point you feel the weight of his frustration with the business of making bicycles.

“I don’t really feel like I’m part of the industry,” Hunter says. “I’m more captive to it. I’m trying to adapt to changes all the time, but I don’t lead in any way or define any trends.”

I see it very differently. Hunter’s bikepacking designs, in collaboration with boutique Canadian bag maker Porcelain Rocket, have been trendsetting in that space. He has a popular line of handlebars and stems produced in Japan’s Nitto factory for the brand SimWorks, and his fanny packs have become ubiquitous in the Western states on riders out for a one-bottle ride. His frames themselves have inspired every other custom builder I can find in my address book. (When I reached out to many of these builders for comment, I received an immediate flood of positive and enthusiastic responses.) If I were to steal and bend a literary phrase, Hunter is a builder’s builder.

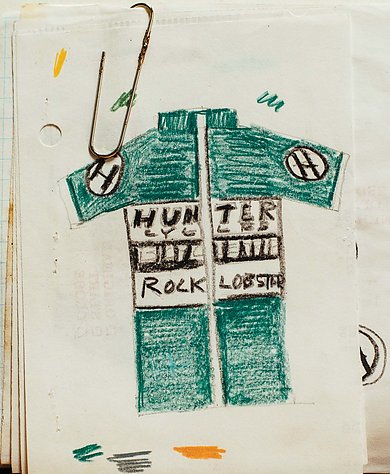

Born in 1972 in Los Angeles, Hunter grew up in Marin County, California, moving around the tiny towns of Ross, San Anselmo and Tam Valley Junction. By high school he’d fixated on bicycles, participating in mountain bike races and dreaming of making his own bikes. He enrolled in the College of Marin’s industrial arts program, and with the encouragement and under the tutelage of mountain bike pioneer Craig Mitchell, an instructor at the college, he learned machining, drafting and design. In 1994, Hunter moved to Santa Cruz, to be closer to the thriving mountain bike and cyclocross race scene, and that same year he started his company, Hunter Cycles.

We head to Hunter’s workshop so I can see what projects he’s been working on. It’s not the first time I’ve visited, but I head into the woodstove-heated, two-car-garage-sized shop hoping to understand something I haven’t quite been able to grasp. I’m hoping to decipher the thread through Hunter’s work, the uniting theme that holds all his disparate efforts together. I look around at the familiar interesting bits: machining equipment older than both of us, a frame jig completely milled and machined by Hunter himself, as well as a leveling table he fabricated specifically for his own needs.

Nothing in his shop is off the shelf, prompting me to think of artist brothers Casey and Van Neistat, who deconstruct consumer-goods packaging and wrappers and reassemble them with their own hand-scrawled labels—a questioning of the branding and hype of our consumerist culture. As far as I can tell, nothing in Hunter’s shop is hyped, marketed, branded, or even bought. Everything screams sincerity and purpose. It is all handmade, and it seems beyond the cheeky critiques some witty artists might make. But, like the Neistats’ art, there is humor in Hunter’s work. His naming of projects would make any corporate copywriter giggle: Smooth Move handlebars, the Racing Couch and Prairie Dog frames, or the Nugz cantilever brake-adjuster doohickeys.

“You can have fun on any bike,” Hunter says. “So, I don’t want to take myself too seriously. At the end of the day, I’m just making a bike frame.”

Regardless of Hunter’s modesty concerning his frames, they are in high demand—and less available than ever before. Hunter seems wearied by every order that comes in, as if he has a fresh argument he knows he won’t win brewing with a girlfriend. Lately, he’s been less interested in taking custom frame orders and is building the bikes he wants to, regardless of customer demand. He’s simply offering his finished work to whoever is paying attention to its availability.

When I wonder aloud how this attitude is congruent with his staying in business, he’s quick to say, “I see myself as a machinist that makes bicycle frames. I always want to have a machine shop. I don’t always need to make bicycle frames.”

“Rick would rather make something than buy it,” Scott Felter of Porcelain Rocket says.

To illustrate this tendency of Hunter’s, Felter points to a month-long bikepacking trip they did together across the Argentinean Andes, crossing one of the southern Andes’ highest passes. “I tried so hard to get Rick to use a new, welded roll-top frame bag on the trip, but he just quietly refused. Instead, he showed up with his own system, made as a oneoff. That’s Rick, he wants to do everything himself. He doesn’t live by anyone else’s rules.”

Among friends like Felter, Hunter’s trail name is “El Condor.” And, like that giant scavenger, Hunter sets his own flight plans, whether on the trail or in the workshop.

“The things people don’t see are more beautiful than the things he’s making for them,” says Felter, who has spent a lot of time in Hunter’s shop. “The fixtures he makes are all custom; you can’t buy anything like it. A machinist operates machines, but Rick makes machines. And bikes are probably the simplest machines he makes.”

Though he claims to be just a machinist, Hunter is truly a designer. His ideals—or possibly what Felter describes as his “fraud syndrome”—dictate that he erase his own hand in the originality of his work, despite the fact that his work clearly shows the sureness of someone who believes in his principles and skill.

“Part of the energy I get is the actual fun of building something new that hasn’t been done before, personally or in general,” Hunter says.

Finding original projects has led Hunter in many directions. His property is littered with the remnants of explored ideas. There’s the barely maintained pumptrack in the yard, first built six years ago, that spurred the idea for his Gopher bike. Hunter didn’t just visit another pumptrack to figure out what a good design should be. Instead, he built his own.

Back in his house, I fumble through some old notebooks to find a list of projects Hunter wanted to take on. The list, from the mid-1990s, not only includes a couple of bike projects, but also features “bags, skateboard, glasses, furniture, shoes and length of bike tubing.” Most of these projects have actually come to fruition: Hunter cobbled his own shoes, and made tables and chairs and designed clothing, but he has yet to make his own length of bike tubing. Though many builders have claimed proprietary tubing, none have fabricated their own tubes—a highly specialized, machine-heavy process.

I find it interesting that Hunter’s focus on making every part of his frames in-house extends to the most basic element of their construction: the tubing. To be the source of all aspects of a finished bike frame takes design sense, skill and imagination. If there’s an end, Hunter wants to be every part of the means. Regardless of the tubing, Hunter’s intention is clear, “I want to make as much of the bike as possible, not rely on mail-order parts. And that just makes them more unique, more my style.”

Adam Sklar, of Sklar Bikes in Bozeman, Montana, met Hunter a few years ago at the North American Handmade Bicycle Show in Sacramento, California. He immediately appreciated Hunter’s bikes, and also the personality behind them.

“He’s super DIY,” Sklar says. “If there’s something that doesn’t exist, he’ll make it.”

When Hunter gets inspired by a new project, he often tears apart older projects for materials. He likes to repurpose, making new things without buying new materials. His process makes it seem like a lot goes unfinished, but in actuality Hunter is usually focused on making one thing work. In his words, he “solves the problem” and then moves on.

This constant need for new problems to solve has led Hunter to make fewer bikes of the classic A-frame variety—the bread and butter of most frame builders. Instead, Hunter’s been developing cargo bikes, break-apart and travel-ready cycle trucks, and even suspension mountain bikes (which aren’t offered for sale because the cost-benefit ratio is too low).

“Most builders make things that are smart business decisions, but Rick just builds whatever he wants,” Sklar says. “It’s inspiring that he’s authentically into what he’s doing, whether that’s good or bad for business.”

One net-loss problem Hunter has attempted to solve twice in the 20 years I’ve observed his work is the rail bike. In 2009, Hunter, some friends and I did a tour on four custom-built bikes made to mount to railroad tracks while remaining suitable for regular trail riding. We pedaled through the Mendocino National Forest, along the Eel River, out to the Pacific Ocean and back inland to Willits, California, searching out old rail lines the entire way. For miles at a time, we’d set up our rigs and attempt to sail along the rails. It was a Peter Pan expedition, and our hearts were as free as children’s. But those first rail bikes were complicated, not too strong, and less than secure on the rails.

Hunter recently revisited the rail bike and made an updated version—a solid machine, totally trustworthy on the rails, and still convertible for singletrack slaying on the way to the next rail line.

“I like to make people laugh, and I think it helps people laugh when they see [the rail bikes],” he says. “It’s a kind of crowd-pleaser. I don’t know why [I make them]. I’m never going to sell them. It’s not a viable transportation alternative. You can’t have a thousand rail bikes on one rail because you can’t go different directions without running into each other.”

All the qualities that set Hunter apart—imagination, humor, technical proficiency and total capitalistic fruitlessness—are present in his rail bike. Its goal is to find a stretch of rail that is literally the only path forward. It leads to a place no other transport could take you. And, in that ultimate scenario, Hunter would simply keep pedaling himself to that place beyond all other means of transit. We might not know when he gets there. But Hunter will be there, and that’s all that matters. The condor flies alone.

![“Brett Rheeder’s front flip off the start drop at Crankworx in 2019 was sure impressive but also a lead up to a first-ever windshield wiper in competition,” said photographer Paris Gore. “Although Emil [Johansson] took the win, Brett was on a roll of a year and took the overall FMB World Championship win. I just remember at the time some of these tricks were still so new to competition—it was mind-blowing to witness.” Photo: Paris Gore | 2019](https://freehub.com/sites/freehub/files/styles/grid_teaser/public/articles/Decades_in_the_Making_Opener.jpg)