Welcome to Issue 15.2

A unique blend of shared excitement and camaraderie that transcends mere thrill-seeking exists within the mountain biking community. In the latest issue of Freehub, we uncover the nuanced layers of connection that define our community. An in-depth report on the groundbreaking inclusion of women in premier slopestyle events and an exploration of the neurological foundations of mountain biking that promote healing and mental well-being are a few among many stories that delve into the diverse ways riders find unity and purpose. In a profile piece on Laura Blythe, a search for purpose leads to a blossoming love for mountain biking on the trails of Fire Mountain in the Qualla Boundary, home of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina. These narratives highlight individual experiences that collectively shape our shared passion for mountain biking.

Dive in and explore the depth of community woven through the pages of Issue 15.2.

My first riding buddy was a woman named Tina. We had shit bikes and boundless enthusiasm. In fact, that was pretty much all we had. We didn’t know how to ride mountain bikes, not really.

Over and over, we pedaled straight up to the edge of disaster and somehow saved ourselves just in time. I guess I’d call it beginners’ luck. It certainly wasn’t skill. Tina took a fearless approach to every descent and laughed off the inevitable bloody knees. I wasn’t any more calculating than she was, and I still have the scars to prove it.

Words by Jen See | Illustrations by Victor Brousseaud

Laura Blythe speaks with a feisty mountain drawl. Her boisterous voice echoes generations of her southern Appalachia forbearers. Today, she calls her bike friends together as they reluctantly eye the snow moving across Soco Gap toward Fire Mountain in western North Carolina. Not one to sugarcoat anything, Laura encourages her comrades.

"Y’all, it’ll be OK,” she says. “We just gotta get movin’.”

The crew reluctantly pulls at zippers and cinches up sleeves, listening for a little more inspiration. Grabbing her sticker-laden Stumpjumper, Laura shouts out while leading up the trail: “It doesn’t matter how slow we are, let’s get goin’.”

Laura has only been riding for four years, but she rallies her group with the grace of a seasoned guide. Despite her newness, she has gone all in—building her skills, her community, and her sense of self. On her journey into mountain biking, Laura has learned to heal complex generational trauma, lead a community, and become a more whole person. Her secret? Follow the right path.

Words by Kristian Jackson | Photos by Derek Diluzio

When Patricia Druwen dropped into the iconic Joyride slopestyle course on the final day of the Crankworx Whistler festival in July 2023, she had a feeling she was inching toward the inevitable—that one day she would compete in front of the world on this same stage at the Whistler Mountain Bike Park. This would be significant, as the globally renowned contest is a competitive high mark that has only been open to men during its 20-year existence.

But she had no idea that day would come so soon. After all, 2023 was the first time that women had been invited by Crankworx to formally session the course. Actual competition still felt a long way off.

“I knew it would come, but not in 2024,” said Druwen, a 17-year-old phenom from Germany who is quickly earning a reputation as the world’s best female slopestyle rider. “I thought in 2025 or 2026, so it was a big surprise.”

Indeed, at the end of 2023, Crankworx and the Freeride Mountain Bike Association (FMBA) announced the addition of a women’s division for the Slopestyle World Championship (SWC), the elite contest series representing the pinnacle of slopestyle mountain biking. The series consists of competition on four “Diamond Level” courses, one for each of the four Crankworx stops: Rotorua, New Zealand; Cairns, Australia; Innsbruck, Austria; and the crowning event in Whistler, Canada.

Words by Nicole Formosa | Photos by Sven Martin

I can still close my eyes and visualize the scene surrounding me as I confronted one of the most challenging realities of my life. Trauma, I’ve noticed, doesn’t leave—even years later.

It was a late April morning and already warm enough for short sleeves in the mountains behind Santa Barbara, California. Mornings are my time to ride, and this road trip was no exception. I enjoy the solitude of getting out on the trail early, and I often climb as the sun rises. It is my time to think and clear my head. Sometimes, it’s also when I wrestle with my past.

By 8 a.m., I was pushing my bike up an old dirt road and realizing California riding was no joke. The doubletrack took a hard right, but to my left was a stunning view of the valley my family and I called “home” for the weekend. I could see rows of RVs leading up to the trees, then only glimpses of these traveling homes speckled in the oak trees.

Clouds blanketed the ocean far off to the west. The nearly hour-long climb that morning had prepared me to come to grips with what my family had just left. I was finally able to say the words, even if just to myself: For the past 15 years, I had been in a cult.

Words by Travis Reill | Illustrations by Chris McNally

There is a place, in the furthest corner of the world, where 12-year-olds will have you reconsidering how good you actually are at mountain biking. To picture this place, imagine any mountain town, multiply the beauty of its scenery to a near-fairytale level, add a lot of cutoff jeans, and pepper in two of the world’s largest public jump lines. This is Queenstown, New Zealand.

As a rider, I’ve been dreaming of spending time in New Zealand since I first laid eyes on its splendor about 18 years ago. In early 2024, I took a month-long trip with a few besties to ride there and get the scoop on what makes this region so special. My findings, it turned out, were a bit unconventional. With a resident population of about 60,000, Queenstown is situated inland on the southern end of the country’s South Island. This medium-sized town sits at the foot of a number of insane mountain ranges and shares its valley with the beautiful Lake Wakatipu. Adventure tourism is Queenstown’s biggest industry, and a diverse array of adrenaline-fueled people flock here from all over.

With a resident population of about 60,000, Queenstown is situated inland on the southern end of the country's South Island. This medium-sized town sits at the foot of a number of insane mountain ranges and shares its valley with the beautiful Lake Wakatipu. Adventure tourism is Queenstown's biggest industry and a diverse array of adrenaline-fueled people flock here from all over.

Words by Blake Hansen | Illustration by Micayla Gatto

As a self-aware species with a seemingly decent understanding of time, humans have a prodigious connection with the past. Our entire understanding of history is built on the knowledge of what happened before our own lives. This relationship, though, has profound implications.

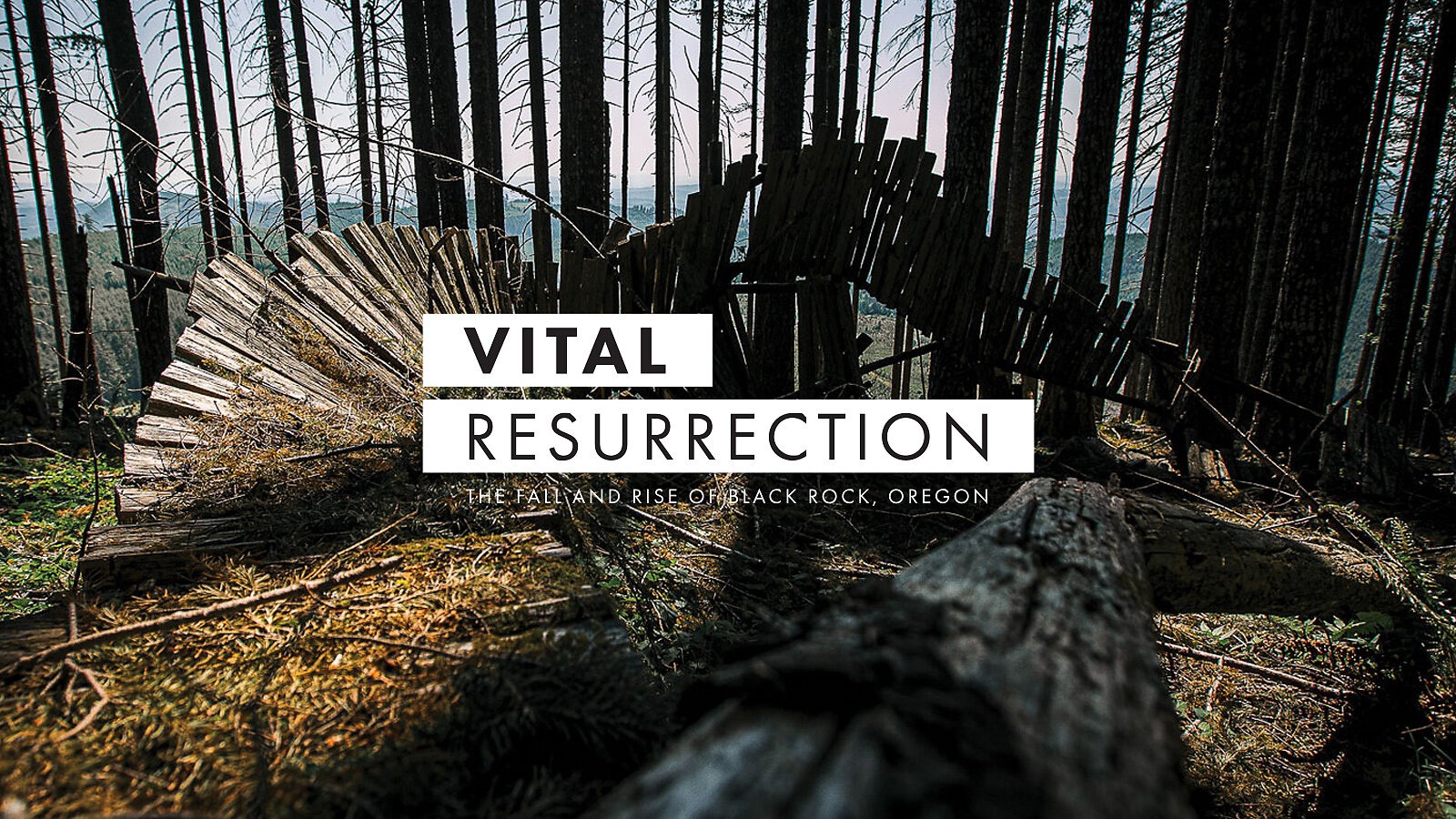

As the late astronomer Carl Sagan famously said, “You have to know the past to understand the present.” In trying to understand the significance of a place and time within mountain biking’s history, it follows that we would seek to draw cosmic parallels with the world as we now know it.

The fire roads of Marin County’s Mount Tamalpais could be reminiscent of Stonehenge, a place where ingenuity tapped into newfound dimensions of the human psyche. The mind-bending wood skinnies of British Columbia’s North Shore might be akin to the Pyramids of Giza—so absurdly ahead of their time that some people believe they were built by aliens. The lines carved into Utah’s red rock spires for the inaugural Rampage freeride event in 2001 could be likened to the Great Wall of China, both feats where the scale of human capabilities were redefined.

Words by Jann Eberharter

Moniera Khan was 54 years old when she finished dead last in her first mountain bike race.

But race results have little to do with her love for riding. Instead, it’s a celebration of what bikes have brought into her life, what her body can do, and her ability to define success on her terms. Whether she’s training through the winter just to cross the finish line or stopping in the forest to look at adorable fungi, she will tell you that she’s an athlete.

“I do athletic things,” she says. “My story is more about delighting in being OK with where I am than a grudging self-acceptance of it.

Words by Danielle Baker | Photos by Robin O'Neill