Inner Revolutions The Brain-Healing Power of Mountain Biking

Words by Travis Reill | Photos by Chris McNally

I can still close my eyes and visualize the scene surrounding me as I confronted one of the most challenging realities of my life. Trauma, I’ve noticed, doesn’t leave—even years later.

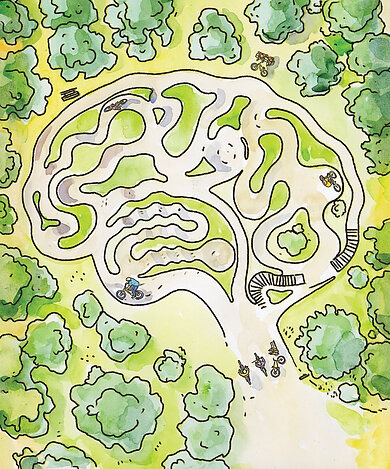

It was a late April morning and already warm enough for short sleeves in the mountains behind Santa Barbara, California. Mornings are my time to ride, and this road trip was no exception. I enjoy the solitude of getting out on the trail early, and I often climb as the sun rises. It is my time to think and clear my head. Sometimes, it’s also when I wrestle with my past.

By 8 a.m., I was pushing my bike up an old dirt road and realizing California riding was no joke. The doubletrack took a hard right, but to my left was a stunning view of the valley my family and I called “home” for the weekend. I could see rows of RVs leading up to the trees, then only glimpses of these traveling homes speckled in the oak trees.

Clouds blanketed the ocean far off to the west. The nearly hour-long climb that morning had prepared me to come to grips with what my family had just left. I was finally able to say the words, even if just to myself: For the past 15 years, I had been in a cult.

I’d only found mountain biking again after the collapse of this high-control church, which culminated with the ousting of its malicious leader. For several months, I watched a manipulative and dishonest man grasp at any strand of the control he once had until the truth of his actions were finally exposed, and all of our eyes were opened to the monster he is.

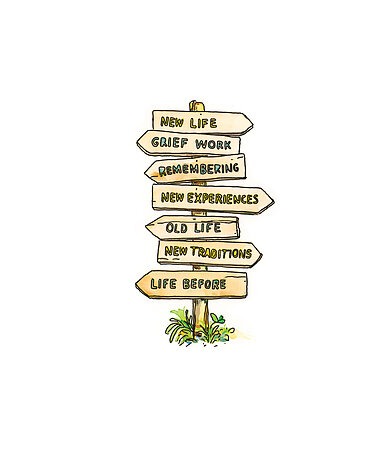

I didn’t return to mountain biking as a means of therapy. Therapy found me through mountain biking. Each ride, early in the morning, I came to grips with what my adult life had been up to that point: hurt, manipulation, control, and the harrowing realization that even worse had been inflicted on female members of the church.

The more I rode, the more I processed. And things seemed to get better.

Over time, I came to realize I wasn’t the only one healing from trauma through mountain biking. And while each rider’s experience is distinctly their own, I connected instantly with stories from others. In some cases, I felt as if they could’ve been sharing my experience. Why, I began to wonder, as my curiosity grew, does pedaling a bike off-road seem to be such a potent method for confronting and moving through personal struggles?

Ravi Almeter is a therapist in Oregon, where he works with a variety of clients, including those dealing with trauma. He doesn’t specialize in sports counseling or therapy, but he is an advocate for physical activity as a means of healing. Almeter, a cyclist himself, sees many benefits of mountain biking from a therapeutic perspective.

“Mountain biking checks so many boxes,” he told me. “It’s exercise, it’s quiet, it’s in the woods. Maybe you’re thinking, or maybe not. Maybe it is a ride with a buddy, and you can talk, but it is passive talk.”

The term “passive talk,” Almeter says, refers to conversations that take place in a casual setting where those involved can feel comfortable letting their guard down because they’re focused on another activity or process. Mountain biking with a friend or in a group can be a perfect setting for passive talk to occur. In fact, our sport seems almost tailor-made for fostering these situations organically. We chat on fire road climbs to pass the time, lingering on the subject of, say, tire choice before veering off to talk about family or work or whatever else is happening in our lives. Mountain biking is just the reason for being there in the first place. Conversation follows.

Almeter notes several other things that can be beneficial about mountain biking. These different aspects become adaptable to the individual rider— one person may pedal to get away from intrusive thoughts, and another may need the space to dig deeper into their psyche.

“It depends on the person and what they need to be challenged to do,” Almeter said. “Say it is social anxiety. Doing an activity like mountain biking is a much easier way [to be social].”

Being told to “be social” may be impossible homework for someone suffering from anxiety. Being told to try joining a group ride presents a much more reasonable task.

What begins as a therapeutic tool can often lead to an identity, especially in the case of activities such as mountain biking which have a heavily physical component. This phenomenon can present its own challenges.

“The times that we notice the benefits [of physical activity] the most is when it is taken away,” Almeter told me. “When it is built into your life, but then you can’t do it anymore, it can leave you wondering why you are triggered, why you are blowing up. It’s because your outlet is gone.”

In other words, someone who participates in regular physical activity can become dependent on that outlet. And if that job ends or the hobby stops, a person can be left searching for a new identity. Some find that new identity in mountain biking.

Finding a healthy physical outlet can be especially true for those who have served in the military. Many veterans returning to civilian life can struggle with the mundane, explained Kenny Stone, the founder of Soldiers on Singletrack, a nonprofit that serves veterans by organizing regular group rides and hosting clinics.

Imagine, Stone says, going from the high pressure, high energy, and high consequence experience of the battlefield to an ordinary job after retirement. One day, your life, or a fellow soldier’s life is at risk. The next day, you’re selling insurance. Both experiences, of course, are valid, but the drastic difference in intensity prevents many veterans from properly adapting to civilian life.

“We seek the edge post-military—the thrill,” Stone said. “And that’s why there’s a huge addiction rate; we’re seeking that thrill.” Stone is a war veteran who suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) while in service. “If you get a TBI, they just lump you and TBI post-traumatic stress disorder together,” Stone said. “Because of those two things, I was having some issues in my life.”

Stone found relief the more he rode his mountain bike. “It was like 180 degrees from where I started,” he said. “I was a completely different person for the better.”

As mountain biking continued to drastically help his mental state, Stone felt compelled to share what he had found with other veterans. So, in the summer of 2022, he founded Soldiers on Singletrack.

“Our main three things are helping provide community, purpose, and challenge,” Stone said. “We are helping the veteran community regain what they feel they’ve lost."

Soldiers on Singletrack has grown quickly, expanding nationwide with members made up of veterans and active-duty personnel. In less than two years, the nonprofit has gained a hefty social media following. Initially, Stone expected to be introducing veterans to mountain biking. He didn’t realize that many had already found the sport and were benefiting from the rush of adrenaline it brings.

“There are tons of veterans already riding. They knew they felt better after riding their bike, but they didn’t have that community piece,” Stone said. “Our rides kind of provide that culture again. We have our own sense of humor and communicating [style] with one another. Most civilians don’t understand that.”

Soldiers on Singletrack has become a resource for military personnel to find that adrenaline rush again, relax, and be themselves. Mountain biking can also provide a sense of accomplishment for many veterans.

“Veterans are very task-oriented people,” Stone said. “You give them a task, and they’ll work on it until they get it, and then they’ll find out how to become more proficient at it.”

At a point in his life when he needed it most, mountain biking gave Stone a similar sense of “task,” whether it was setting his fastest time on a descent or working on something minute, such as foot positioning. He’s also noticed the benefits that getting riders together to focus on these skills can bring. Seeking out professional mental help services is a barrier many veterans struggle to overcome, but on simple mountain bike rides, Stone has seen some take the first steps to address their issues.

“I’ve seen complete strangers who, by the end of the day, are sharing some pretty deep stuff,” Stone said.

To help foster communication among its members, Soldiers on Singletrack maintains an active phone network and discord server that veterans can access to reach out anytime. Stone employs the philosophy that there’s always 15 minutes for a conversation, regardless of what is happening.

This same sense of commitment to community is shared at Sacred Cycle, a Colorado-based nonprofit that aims to help survivors of sexual abuse.

“Sacred Cycle’s mission is to help heal our community by empowering survivors of sexual abuse and sexual assault through therapy and mountain biking,” said Alan Luu, who serves on the organization’s board and works as one of its program directors. Sacred Cycle offers participants one-on-one rides with coaches at least once a month, as well as group rides with fellow members and other coaches.

In addition, it hosts weekly group rides—open to the community—which can provide more opportunities for camaraderie and connection to participants who feel comfortable in a group setting. Paired with mountain biking, Sacred Cycle offers participants several therapeutic activities from local practitioners, such as equine therapy, yoga, and art classes.

“I’VE SEEN COMPLETE STRANGERS WHO, BY THE END OF THE DAY, ARE SHARING SOME PRETTY DEEP STUFF.”

-Kenny Stone

“We also partner with local trail associations to give back and help build and maintain trails,” Luu said.

Through Luu, I was introduced to program participants Jordan and Tara. For safety reasons and to preserve their anonymity, both rider’s names have been changed. Tara and Jordan joined Sacred Cycle in 2021. Initially, Jordan was terrified by the thought of mountain biking. But, over time, she came to look at the sport differently.

“Mountain biking made healing seem tangible,” she said. “The idea of acknowledging [my sexual trauma] was terrifying—so terrifying that it made the idea of mountain biking somehow seem less terrifying.”

Jordan’s healing came through therapy, coaching, and mountain biking, among other things. As she progressed as a mountain biker, she found she was growing and healing as an individual.

“If I could face my fears and anxieties on the bike, then I could also face them during my healing,” Jordan said. And while mountain biking has Jordan hooked, the community she found through Sacred Cycle is irreplaceable to her.

“To finally share my truth, my story, and to speak about my sexual trauma for the first time was a huge relief,” Jordan said. “Even though we started as strangers, the girls I met through Sacred Cycle quickly became a lifeline for me.”

Tara joined Sacred Cycle after doctors found a cyst in her brain. Healing and regaining her health not only meant having the cyst removed but also confronting past trauma. Similar to Jordan’s experience, Tara found comfort in the community Sacred Cycle provided.

“When we met as a group of survivors for therapy, I finally heard others had been thinking and feeling very similar thoughts I had been having all my life,” Tara said. “I thought I was crazy and just having irrational thoughts, but it was just my past trauma manifesting into my present situations.”

Tara’s healing journey, she says, corresponds so closely to her mountain bike progression that the two seem completely interlinked. At one point, during a race, she had an experience that pushed her to reach another level of confidence.

“I descended a technical switchback that I would have never considered attempting two years before,” Tara said. “With my new attitude and support system cheering me on, I was able to look where I wanted to go, lean into the turn, and ride through feeling empowered with skills and strategies that guide me to recovery from sexual abuse.”

Therapeutic benefits that can occur on group rides, during skill-building exercises, or within deep conversation are rooted in chemical changes in the brain. Stefanie Faye is a neuroscience specialist, educator, and author whose work delves into the inner workings of the brain and the mechanics of mindset and self-regulation. Trauma can rewire the brain, Faye says, and a lot of this process has to do with our ears.

“There are mechanisms inside our middle ear that have tiny little muscles,” Faye said. “Those muscles tighten or relax according to the frequencies that we’re surrounded by. That tightening and relaxing has a lot to do with which nervous system state we are in.”

Screaming, yelling, gunshots—these spikes are registered by the middle ear in addition to all other input from the surrounding environment. If auditory stimuli come from traumatic experiences, future similar experiences will be associated with that trauma. The more it happens, the more our brains begin making connections and processes— similar to how computer algorithms expedite and organize patterns of input—to predict when it will happen again.

“When there are certain frequencies, particularly these lower bass, and very high amplitude frequencies, the mechanism inside the middle ear gets us to only really pay attention to threat and danger,” Faye said. This is typically when a person enters into what many of us know as “fight or flight” mode.

But this isn’t the only response. Some may disassociate, while others may try to please. Whatever the response, the trauma triggers the algorithm in our brain, which essentially automates how to best get out of the situation.

“Our brain is experience-dependent. So it builds algorithms based on experiences,” Faye said. “When we enter new data, it changes the algorithm.” Traumatic experiences that, once built our algorithms, can be replaced, though Faye acknowledges that it takes time and repetition. Eventually, our brains receive enough input to disrupt the old algorithms. Only then can change occur. Groups like Sacred Cycle and Soldiers on Singletrack are helping to facilitate this rewiring of ingrained patterns by intentionally providing a place for their participants to heal.

“New voice frequencies, new phrases, new ways people are looking at each other, their body movements— all of it is in more of that paradigm,” Faye said. “This allows for new data to now enter that person’s system that says, “Human relationships can be safe, my environment can be safe.’”

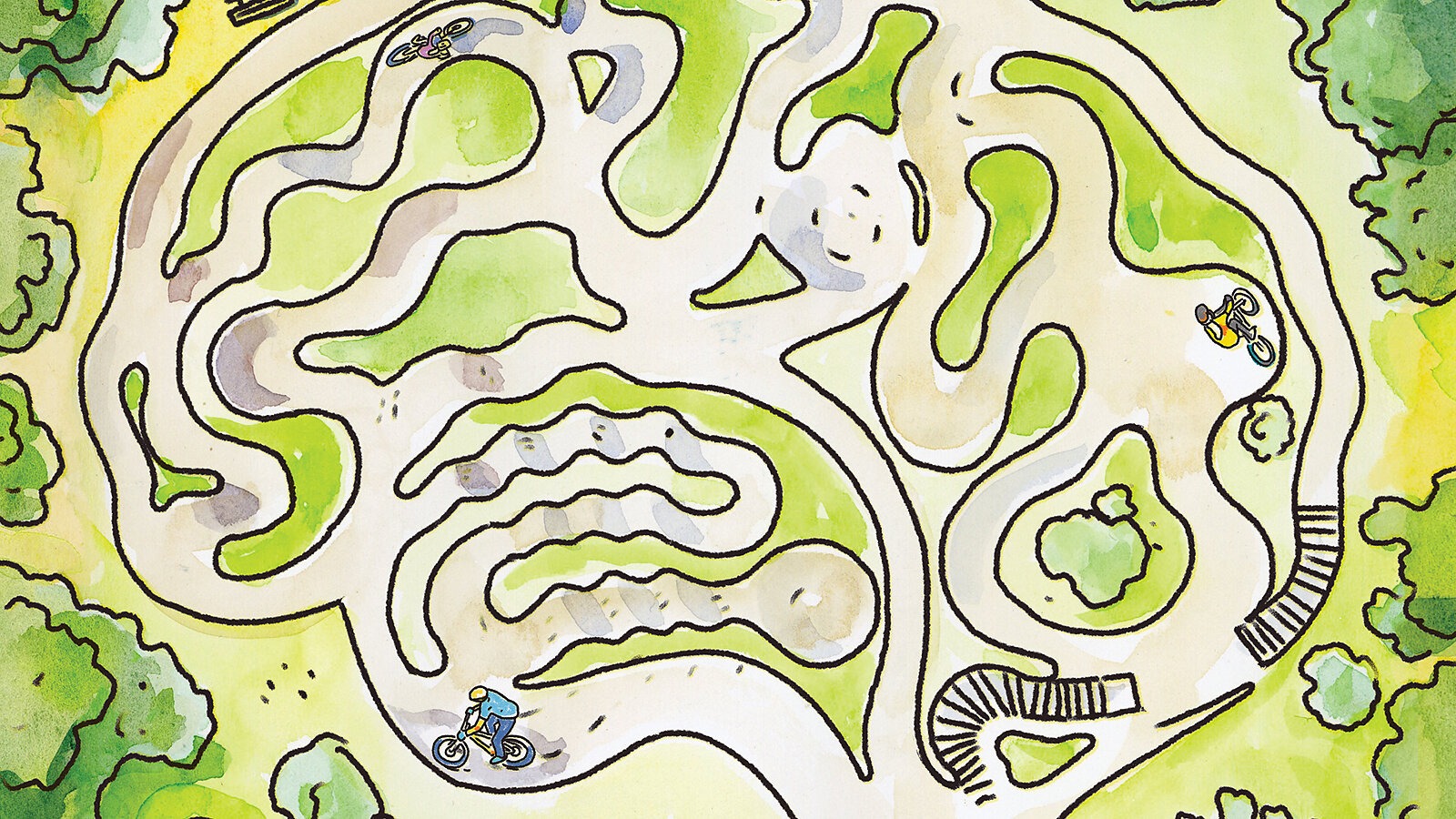

While its algorithms are being rebuilt, the brain is also benefiting from the motions of mountain biking, specifically the rhythmic aspect.

“Any cross-body motion where different limbs are being in rhythm is very helpful for activating cross-hemisphere [brain] networks,” Faye said. She also notes that mountain biking is simply a good release of energy while we are rebuilding connections. When triggered, the brain conducts the rest of the body in its trauma response. Our heart rate increases, blood flows to our limbs to prepare for a physical response, and our senses strain to detect threats. With no outlet for this energy, it gets recycled in our bodies.

Mountain biking mirrors the increased heart rate, blood flow, and alert senses but with a rewritten algorithm. “If we have this sped-up heart rate and stress level but can channel it into an intentional movement that is not threat related, our body and our brain can then make a different story about this energy,” Faye said.

I didn’t know about brains operating like algorithms or about the very real benefits that stem from passive talk when I pedaled up into the mountains above our RV spot near Santa Barbara. At that point in time, I was just trying to make sense of my own emotions.

Perhaps it’s working. Perhaps my algorithm is beginning to be rewritten. Now, as I make my way up fi the road climbs, I don’t find myself needing to process hurt and pain with the same intensity as I did during that trip to California. All the while, I thought I was just riding my bike, but I was actually engaging my brain’s hemispheres, retraining muscles in my ear to be calm, and teaching my body that it doesn’t need to perpetually operate in fight or flight mode.

Looking back, the mountains of Santa Barbara represented fear and panic and hurt and lostness. Now, at home, Oregon’s mountains feel like something else. They feel like growth and healing.

And now, strangely, I feel like my community also includes groups like Soldiers on Singletrack and Sacred Cycle. While I will never fully understand the unique experiences of those they work with, I do understand their connection to mountain biking and the healing it brings. There’s one thing I think we all know instinctively: The swirling thoughts shut off as soon as we head back downhill.