Welcome to Issue 13.2

As much of the Northern Hemisphere embraces a new riding season, Freehub is proud to present its new edition—an evocative book brimming with stories of hope, resilience and community cooperation. During a time when our world feels increasingly dark and tumultuous, we’ve found comfort in the unwavering light shone by the broader mountain bike community. Our cover story celebrates the inspiring life of Angelo Washington, a former semipro baseball player who sustained a career-ending injury only to reinvent himself as a downhill racer and coach dedicated to showing how bikes and a positive outlook can open new realms of possibility for our youth. We look at how a Diné (Navajo) mountain biker named Nigel Horseherder James has rallied his entire reservation around a home-grown enduro race he calls the “Rezduro,” raising awareness of mountain biking as a means of reconnecting indigenous people to their ancestral land. Stories like these are what connect us all. Welcome to Issue 13.2.

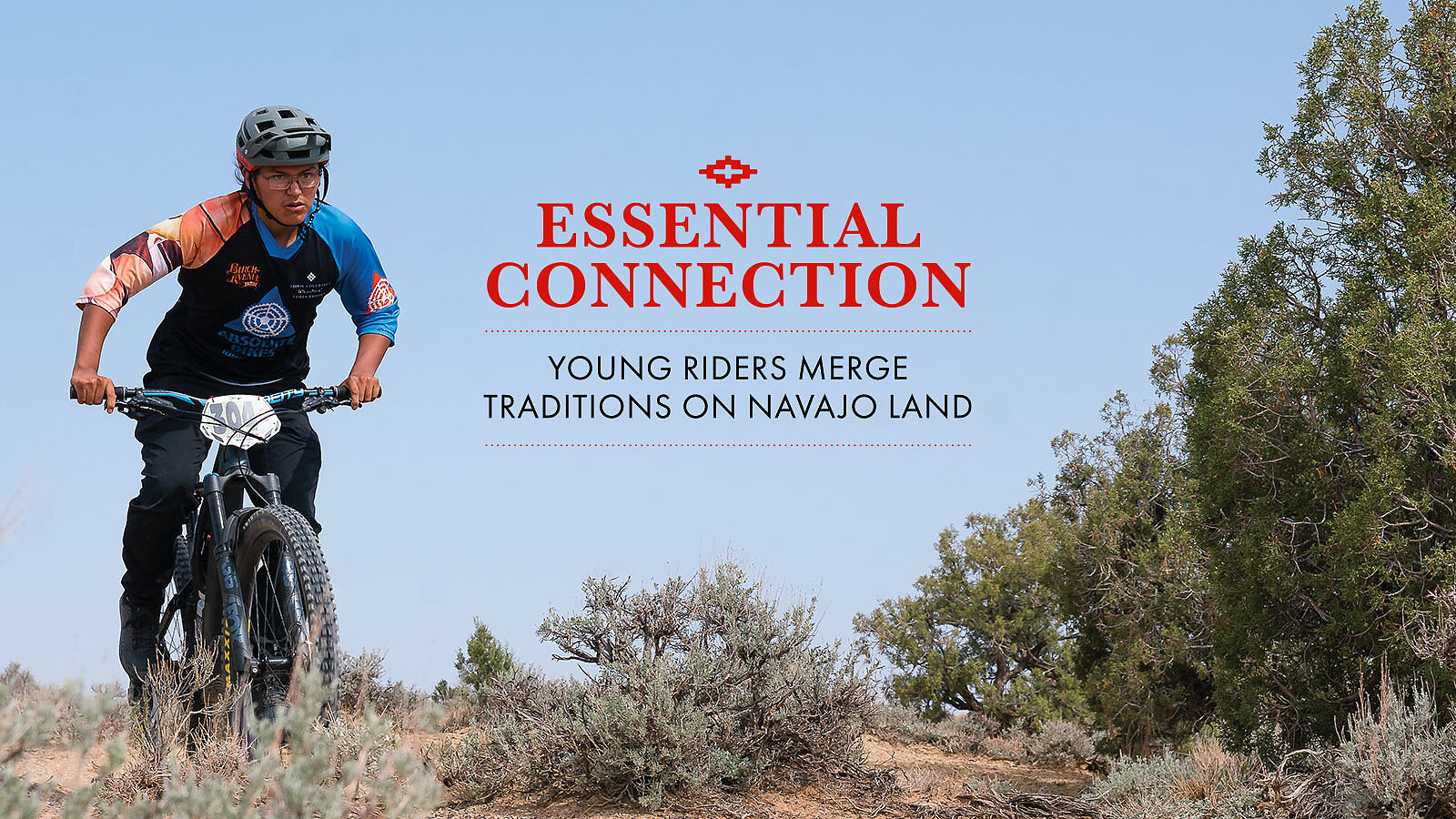

A faded yellow tag hangs from a small juniper tree alongside an empty dirt road, a solitary directional marker in a vast desert. A sandy wash to the right leads to the top of a hill, where a horse corral shows the first sign of life since the turnoff onto “Indian Route 4,” some 23 miles back in Second Mesa, Arizona. Just beyond the corral is a house with a canopy stretching several feet out from the roof.

It’s the residence of Nigel Horseherder James, a Diné (Navajo) mountain biker and organizer of the Rezduro Invitational, an enduro race on Navajo Nation land near Hard Rock, Arizona. Nigel lives here with his mother, Germaine, and his father, Marvin, and their house is the de facto race headquarters.

About 30 yards from the house is a large teepee and next to that is a hogan, a traditional, one-room Diné home insulated with packed earth. The doors of both dwellings face to the east. From here, one can see most of the surrounding landscape, a semi-arid array of rolling hills punctuated by sage, juniper and pinyon pine rooted into the washes and even the cliffs of the surrounding mesas. It doesn’t look like a race venue, but throughout these hills are scattered the one ingredient needed for a mountain bike race: trails. And this weekend the Navajo Nation will host its first-ever enduro race, which Nigel refers to as simply the “Rezduro.”

Words by Josh Conroy

On a warm August evening in 2006 I finished riding my bike in the backyard and got online to see what was going on in the mountain bike world. To my surprise and amazement, I came across a live slopestyle contest that was being streamed on the homepage of Pinkbike. The event was in Whistler, British Columbia, and it was part of a huge mountain bike festival called Crankworx.

Up to that point, I’d never seen or heard the term “slopestyle,” but the longer I watched, the more strongly I connected with what was going on. It was exactly what I was striving to do in my backyard, but on a professional level.

“Come watch this!” I shouted to my family, who rushed over to watch the first of what would be many slopestyle contests we’d see together.

I went to bed that night manifesting what the next 17 years of my life would look like.

Words by Brett Rheeder | Photos by Colin Meagher

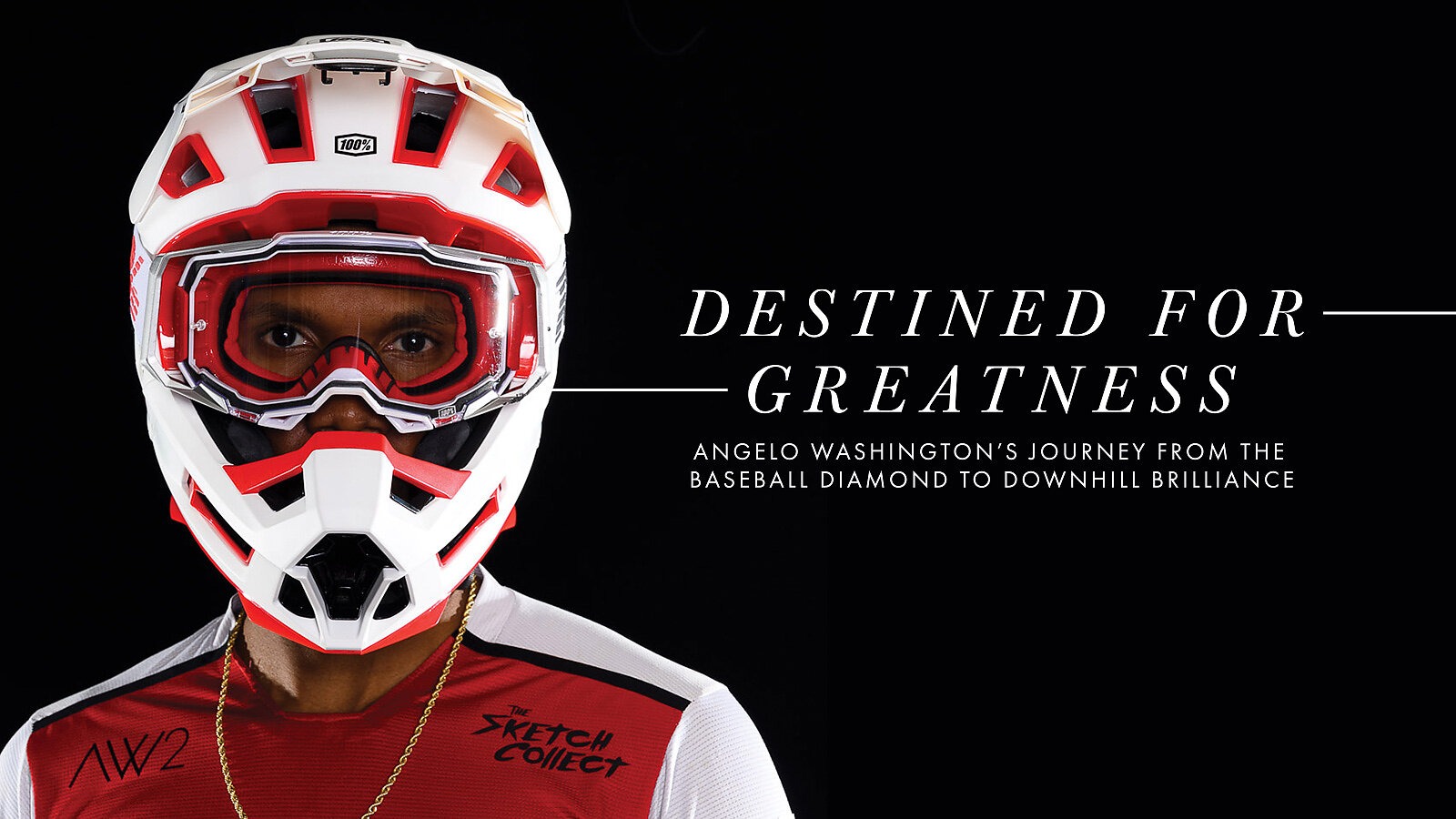

Dig back far enough through Angelo Washington’s YouTube channel and you’ll find “The Experience.” Posted at the end of 2014 Washington’s first year of riding—the video captures one of his earliest forays on his new bike, a clapped-out, 26-inch, gunmetal gray Dawes Roundhouse he scored off Craigslist for $300. The shaky, pixelated GoPro footage shows Washington’s point of view, which looks down on his long stem and narrow handlebars as he navigates the trails at Powhite Park in Richmond, Virginia.

When Washington’s tires leave the pavement and hit dirt, red text sprawls across the top of the screen. It reads, “No turning back now!” There is no introduction and no narration; just five minutes of newbie mountain bike action. The climax of the video comes at the three-and-a-half-minute mark, when Washington stuffs his front wheel into a root and dives headfirst over the handlebars. The viewer is then treated to a slow-motion replay of his crash set to an orchestral soundtrack, which ends with Washington splayed out in the leaves.

What’s remarkable about this video isn’t the clip itself, although it’s endearing in a home-movie kind of way. Rather, it’s a fascinating glimpse of Washington’s first deep dive into mountain biking, which makes his extraordinary skills progression all the more impressive. Today, if you race downhill in the southeastern United States, you probably know Angelo. After his first racing season in 2016, Washington, now 36, quickly blazed through the downhill amateur ranks. In 2020, he moved up to racing Category 1 and now receives support from Commencal, 100 Percent and Etnies.

Words by Jess Daddio

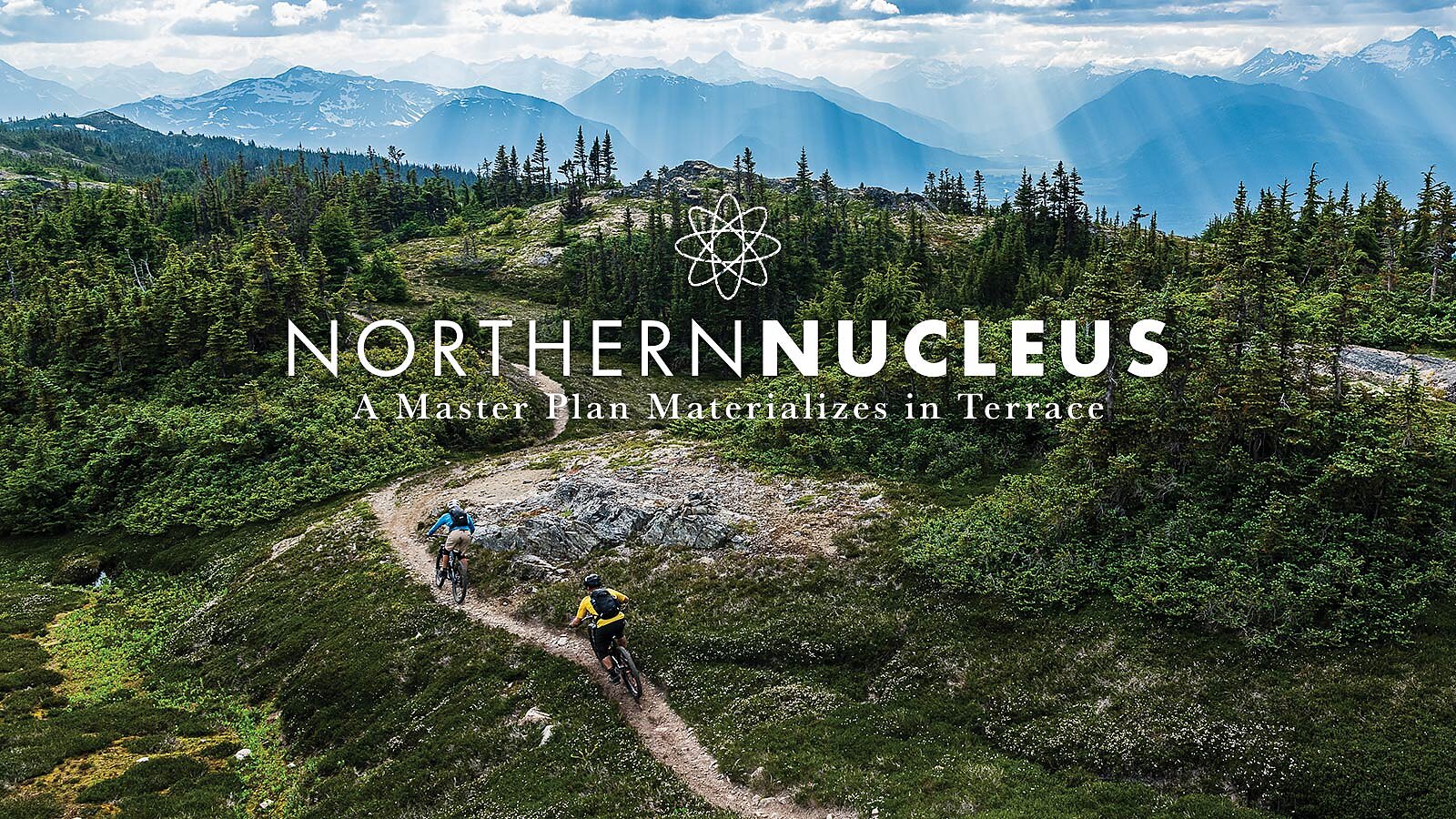

With remoteness comes responsibility and the residents of Terrace, British Columbia have no shortage of both. Though the small city is only about halfway up this sprawling province, it’s considered to be “northern B.C.” by virtue of the fact that it’s nearly a 17-hour drive from Vancouver—roughly the same distance between Vancouver and San Francisco. But no matter how “north” is defined, Terrace is a long way from anywhere, and this remoteness breeds a self-reliance and sense of shared responsibility that permeates every aspect of this tight-knit community.

At first glance, the town of 12,000 people bears a strong resemblance to Squamish, B.C. in the early 2000s, set in a pristine river valley with budding climbing, paddling and mountain biking scenes. The gritty downtown core is bursting with color from giant murals painted by local First Nations artists, and strangers still smile and say hello on the street. With scarce social amenities, the great outdoors is the living room of the locals, and that’s just how they like it.

When it comes to mountain biking, Terrace was a late adopter of the sport, especially compared to more established northern locales such as Prince George, Burns Lake and Smithers. While most of these communities are nestled on the Chilcotin Plateau, where the terrain is more closely linked with the drier regions of the province’s interior, Terrace is an anomaly perched squarely in the crosshairs of the Coast Mountains. Here, four-inch rainstorms are common, nourishing a labyrinth of root beds woven over grippy granite slabs and perfect golden dirt. The steep, heavily wooded valleys are dominated by western hemlock and red cedar, dictating a decidedly technical style of riding.

Words by Ben Haggar | Photos by Mattias Fredriksson

On a frosty fall morning on a farm outside the lakeside community of Sandpoint in northern Idaho, Jason Welker musters the troops. The Pend Oreille Pedalers (POP), the local biking club, has rallied some 30 volunteers in addition to a passel of kids, a pack of dogs and a Kubota tractor. Their task: scratch in a track for the club’s annual cyclocross race in four weeks.

With the intensity of teenagers cleaning up a house party before their parents get home, the volunteers get to work raking, scraping and chopping a route through the doghair hemlock and fallow fields. Three hours and three miles later they are, improbably, done with the course. Lounging amidst hay bales afterwards, Welker, the club’s executive director, and crew contemplate costume ideas and heckling sections for the race. It’s the sort of idle spitballing that usually accompanies bikes and beers, but given the frenetic energy of the course build, the prevailing sense is that the Pedalers will pull it off with gusto.

Sandwiched between the world-class skiing of Schweitzer Resort and Idaho’s largest lake, Sandpoint is one of the fastest-growing small towns in the United States according to U.S. Census Bureau data. Although the landscape of North Idaho now attracts a steady stream of private planes to the tiny Sandpoint Airport, it’s notoriously been a home for those looking to duck under the radar.

Words & Photos by Aaron Theisen

Dimly lit by a sole bulb and traces of moonlight, I hunched over my workbench, eyes fixed on the soft glow of my phone. On the screen a blurry, middle-aged man wearing greasy blue coveralls and gold-rimmed glasses glanced up at the camera, as if to make sure I was still paying attention, while he slowly demonstrated the correct way to turn a knob.

It was my fourth time watching this video and, by now, his mannerisms felt familiar. When the man held up a rubber hose to illustrate how to check for leaks, I mimicked his Southern drawl as we both declared in unison, “Safety rules are your best tools!”

Learning online was nothing new for me, but this wasn’t like figuring out the proper way to bleed brakes (olive oil is not a substitute for mineral oil), or how to give the world’s greatest high-five (look at the elbow not the hand). This was different; I was about to open the valve on a thick steel canister containing more than enough flammable gas to engulf my tiny workshop in flames. And without anyone around to talk me out of it, or at least check if I was doing it right, I pressed on.

Words by Skylar Hinkley | Photos by Kipp Hinkley

The mid-morning light shines through the windows of an historic diner in Knoxville, Tennessee, illuminating a décor that is said to have changed little since the eatery opened its doors in the mid-1950s. Occupying one side of a booth is Alex Clark, his mustache and dirty blonde hair matching the boundless energy of a 27-year-old hungry to take on the world. At this moment, though, Clark is mostly hungry for a heaping plate of pancakes and scrambled eggs.

Amid the clanking of dishes and the distinct smell of diner coffee, Clark enthusiastically describes the rapid proliferation of trails in the Greater Knoxville area—where the rolling foothills just outside of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park provide abundant relief for gravity-fueled fun. With more than 80 miles of trail in the Knoxville area alone, it’s easy to understand how a quick, half-mile pedal from this north Knoxville diner can bring us to the trailhead of the Sharp’s Ridge Veterans Memorial Park, the perfect place to burn off a greasy-spoon breakfast.

Though the majority of Knoxville’s singletrack lies in the city’s southern reaches, Clark is keen to show off the diversity of Sharp’s Ridge, one of the town’s first sanctioned riding areas and a prime example of the success achieved by the local Appalachian Mountain Bike Club (AMBC), a chapter of the International Mountain Bicycling Association’s (IMBA) Southeast regional division. While elements of the original rake-and-ride lines remain at Sharp’s Ridge, a wide variety of purpose-built mountain bike trails now cover the ridge, offering everything from classic singletrack to intermediate jumps and adaptive-oriented trails where adaptive riders can knock out loops.

Words by Brett Rothmeyer