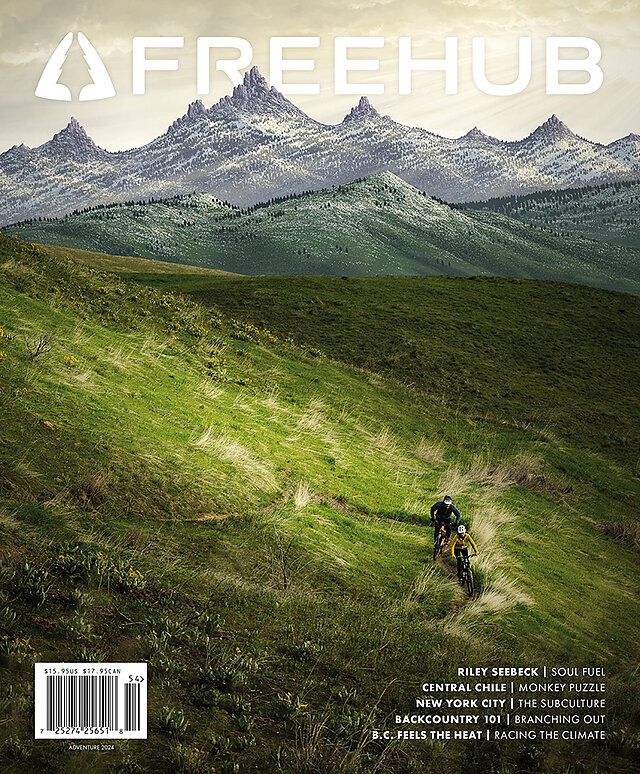

Welcome to Issue 15.4

When we push ourselves to new heights, we take on a higher form of being. This edition of Freehub examines the theme of “adventure” from new angles and with a fresh perspective. Korey Hopkins reports on an East Coast group’s first-ever foray into remote terrain. Andrew Findlay and Kari Medig explore the backcountry and frontcountry of Chile as they learn about the country’s thriving mountain biking scene. Matt Coté offers a sobering look at Canada’s increasingly dry and hot summers, and how race promoters are adapting to continue hosting events. These stories, along with many others included in this edition, highlight the multi-faceted nature of adventure and uncover why its meaning is more than just big rides, long days, and heavy terrain.

Harry Utsal is tall and skinny, making the coil-sprung 29’er underneath him look like a play bike. He maneuvers it with the kind of leverage that long limbs obscure—subtle corrections and weight shifts are mostly imperceptible but add up to microseconds, then seconds, then minutes at the end of the day.

Except no one’s timing him. “Man, I wish there was still a race here,” says Utsal as he collects himself under the canopy of a giant cedar tree on Revelstoke, British Columbia’s Boulder Mountain.

Words by Matt Coté

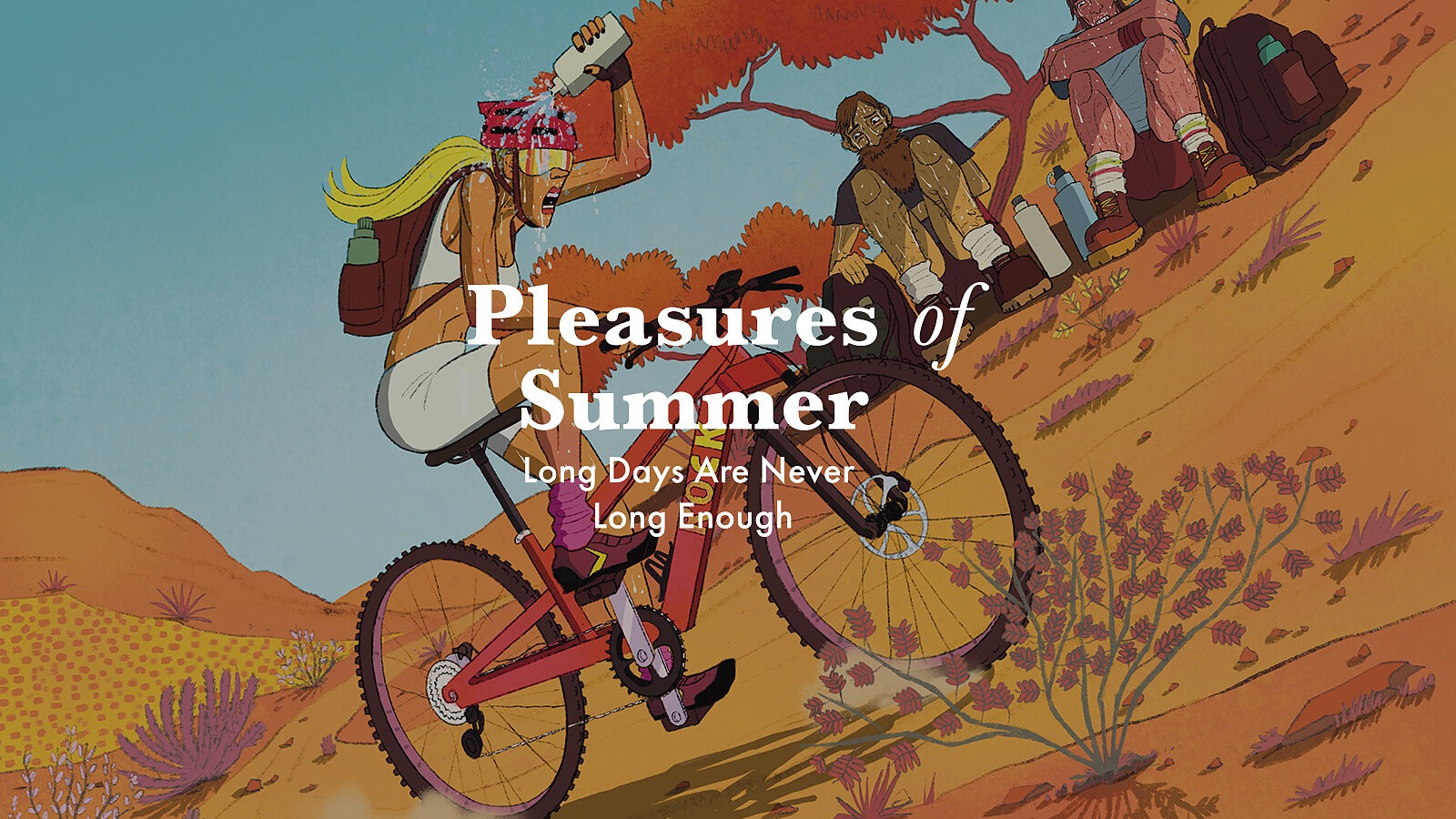

By the time you read this story, it’ll be fall. You’ll be riding through the last golden aspen leaves in the high mountains, dreaming of powder runs, or preparing for winter escapes to the desert.

I’ll be here in coastal California, watching storms form in the North Pacific and imagining perfect winter swells. We all have our dreams to chase. As I sit here in my favorite coffee shop, watching the ceiling fans spin, it’s still peak summer—the season for rides that are too long on days that are far too hot. It’s the time of popsicles and swimming holes and that long, lingering twilight that seems to last forever. If you don’t go skinny dipping at least once, did summer happen at all?

Words by Jen See | Illustration by Jacopo Degl’innocenti

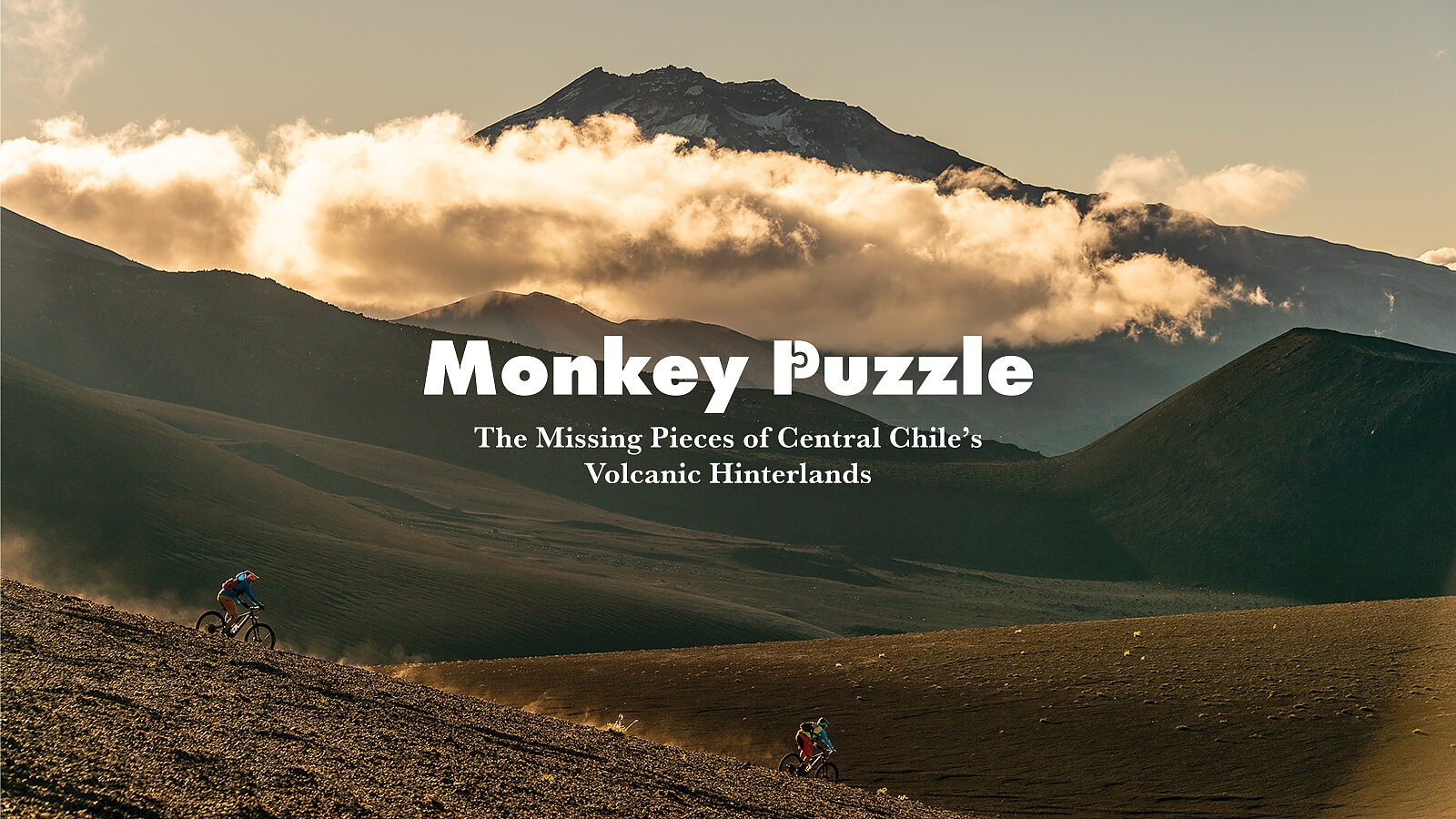

The laws of physics are immutable. In Newtonian mechanics, momentum is the product of an object’s mass and velocity. This could explain why Victor Abarzua—a man who is 6 feet, 5 inches tall and weighs 244 pounds—nearly leaves Ernesto “Máquina” Araneda in a puff of volcanic ash after straight-lining a 30-degree cinder cone on Volcán Batea Mahuida, a plateau-shaped volcano that straddles the border between Chile and Argentina.

When he was only 14, “Máquina” (Machine) was already a Chilean national mountain biking champion and went on to be a Pan-American Games bronze medalist and a World Cup Masters silver medalist. Now, he has young kids and works as a full-time guide, occasionally squeaking in an epic race when he can find the time.

Words by Andrew Findlay | Photos by Kari Medig

I remember my first mountain bike ride like it was yesterday. I was 11 years old, and my uncle—thinking I might have a knack for it— lent me a 20-inch Mongoose full suspension bike that had to have been from Walmart or something.

He shuttled me and a crew of other neighborhood kids up for a rip down a trail in Trabuco Canyon outside Lake Elsinore, California. I had never ridden anything other than a BMX bike, so “gravity” riding was a completely new experience for me. There were switchbacks, baby head-sized rocks, and bone-dry soil. Until that day, I’d encountered none of those things on my usual neighborhood cruises. Amid a cacophony of squealing rim brakes, I remember really connecting to the feeling of not knowing how to stop. My skinned knees from that afternoon healed and faded quickly, but the thrill has stuck with me. Everything from that afternoon is burned into my mind—crashing multiple times, the colorway of my bike, the speed. As mountain bikers, our first rides are visceral experiences.

Words by Blake Hansen | Illustration by Micayla Gatto

Across the churning waters of the Harlem River from Yankee Stadium, New York City’s ultimate temple of sport, lies Highbridge Park. Here, on the tallest, steepest hills in Manhattan, a heavily forested slope above the river is home to a twisting network of purpose-built mountain bike trails.

Highbridge is gritty and emblematic of the working-class neighborhood surrounding it and, if you didn’t know about its trails, you’d be easily forgiven for missing them. First carved into the hillside in the early 2000s, Highbridge’s bike trails came to be after years of negotiations. Namely, its advocates were seeking an answer to mountain biking’s most classic question: “Why can’t we ride here?”

Words and Photos by Max Ritter

Every accomplished photographer is driven by foundational forces that provide the inspiration needed to harness a variety of elements into a consummate vision.

For photographer Riley Seebeck, the fundamental impetus behind his work is a profound reverence for the majesty of nature and the ever-changing patterns it reveals. The Washington state-based lensman is mesmerized by landscapes, and he spends most of his free time exploring remote mountains and forests in search of natural tapestries and the light that will draw out their subtleties. In the following pages, Seebeck shares the minutiae behind some of his favorite mountain biking images.

Photos by Riley Seebeck

One day this past June, Harlan Price gathered a group of riders before setting out for a day of backcountry riding in the George Washington and Jefferson National Forest in western Virginia.

“From this parking lot, we are about an hour and a half away from the nearest shock trauma hospital,” Harlan said. “An evacuation from the trails we are riding today—about half a day away.”

These sober words weren’t meant to scare riders Jali Fernando, Maddie West, and Trae Shelton, but rather to set expectations and provide a reality check to these newcomers to remote, unsupported, adventure mountain biking.

Riders who are new to backcountry excursions are part of a growing demographic of clients for Harlan and Phoebe Price’s Take Aim Cycling, a company that provides guiding, coaching, and shuttling services in and around Shenandoah Valley. This trend mirrors a larger explosion of visitation to public lands for outdoor recreation that spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic and has remained steady.

Words and Photos by Korey Hopkins