The Wild Southwest Passionate Trail Communities Sprout Near Durango

Words by Jennaye Derge | Photos by Anne Keller

Cowboys often roam the streets of Durango, Colorado. Men with big mustaches and women in snug corset dresses wander the town’s sidewalks among the locals and tourists. They’ll offer a tip of the hat and a “howdy” to passersby, hinting that wherever they came from was wild and lawless, and that they’d love for you, too, to step back from the modern world and into one in which simple pleasantries and quaint acknowledgments were still the norm.

These cowboys and cowgirls are mostly actors playing parts related to Durango’s Wild West history for the amusement of visitors but, for locals, they give a nod to the settlement’s rough and dusty roots. A town born from grit. A town born in the high country of southwestern Colorado.

Durango’s trails reflect the region’s rugged qualities. Most were built in vast open spaces with little oversight and reckless abandon—rowdy kids beating in paths or herds of horses wandering through sagebrush fields.

One of town’s most popular trail systems, Horse Gulch, was once a free-for-all on county land. Longtime locals recall how the open space acted as an unofficial dump for discarded tires, washing machines, and refrigerators. The debris littered the road and gullies. Rabble-rousers drove their trucks or dirt bikes up the mile-and-a-half-long doubletrack to party on weekends. Back then there were no official trails, more bonfires than bicycles, more single-use plastic than singletrack, and more gun-shootin’ kids wreaking havoc than crushing berms.

Horse Gulch is now a mountain bike playground filled with meticulously cared-for trails. Just a mile from the heart of downtown, it’s quick and easy to get to—an outdoor church of sorts for those seeking an accessible and quiet natural reprieve. The land was purchased and conserved in the early ‘90s and cleaned up by Durango’s trail advocacy group, Trails 2000 (now Durango Trails), before being released back to the community for more nonmotorized recreation.

The fact that Durango now boasts 300 miles of natural surface trails within 30 miles of town is why Trails 2000 changed its name to Durango Trails. Its first name alluded to the founder’s goal in the early ‘80s to build 200 miles of trails by the year 2000. The organization has now far surpassed that, building and maintaining trails that locals can access from their front doors regardless of where they live in town.

“I’ve ridden in a lot of places, and there’s a lot of places that have great trails, but I can’t think of any place that has the variety and the convenience,” says Travis Brown, a local professional cyclist.

Durango’s in-town trails vary enough in geological surfaces and ecological surroundings to keep anyone on their toes and entertained. In some zones riders pass through desert sage on rocky, loose dirt. In other areas—only a few miles away—singletrack weaves among ponderosa pines and woody oak while skirting ridgelines made up of dark shale.

This trail diversity might be why so many professionals call Durango home. Speedsters who played a part in shaping modern-day racing such as Greg Herbold, Ned Overend, Missy Giove, John Tomac, and Todd Wells, are all here. A growing number of the next generation of top mountain bikers are here too—Sarah Sturm, Howard Grotts, Sofia Gomez-Villafañe, Payson McElveen, and Christopher Blevins are common fixtures of the local trails.

The roadies also love it. Sepp Kuss, a recent UCI World Tour breakout climbing phenom, was born in Durango and still spends time on its quiet country roads when he isn’t battling for stage wins at the Tour de France or the Giro d’Italia.

Elke Brutsaert, a former pro downhill racer, is a cycling coach at Fort Lewis College, Durango’s small liberal arts school known for consistently producing some of the best cyclists in the country. Brutsaert caught the trail bug when she was in her 20s. She was discovered by Schwinn when she was 25 and raced professionally with them for a decade. Her accolades include UCI World Cup wins, multiple NORBA National Championship titles and two X Games gold medals.

She attributes part of her success to time spent riding Durango’s rough and rowdy trails, particularly the Haflin Creek trail she often trained on. For her, it was more for fun than work. The downhill track still exists as it did back then—3.9 miles, 3,000 feet of descent, flowy at the top, loose and exposed at the bottom. There are fewer trees because of a fire many years ago, and maybe a few more people to dodge, but it’s still the same fast and wild trail.

“Haflin was amazingly fun—more fun on a cross-country bike because it was sketchier. We were just adrenaline junkies. Every time we could tick that box and hit that adrenaline punch, we were pumped. Especially if you can do it without crashing.”

—ELKE BRUTSAERT

“Haflin was amazingly fun—more fun on a cross-country bike because it was sketchier,” Brutsaert said. “We were just adrenaline junkies. Every time we could tick that box and hit that adrenaline punch, we were pumped. Especially if you can do it without crashing.”

She recalled the days of her and her then-partner, former pro downhill racer Missy Giove, taking some poor schmucks up to the top of the trail, not knowing what they were getting themselves into by trying to follow her and Giove down.

“Those guys just couldn’t anticipate it because we had already dropped them and then they’d come to those sections and just totally wipe out,” Brutsaert said.

“We’d always get ourselves in some sort of debacle with these dudes that we’d drag out there and they’d not be able to make it down the hill.”

Durango’s bicycle culture is built on much more than gnar, though. Robust teams with abundant coaching and many bicycle-related events all bring bike lovers together throughout each riding season.

Local resident Dave Hagen played a key role in fostering Durango’s strong cycling culture. An alumnus of Fort Lewis College, Hagen coached junior racers on campus. Many of the young riders loved it so much that they later attended Fort Lewis and joined the cycling team. The college’s team kept getting bigger, so Hagen was invited to help with coaching. Eighteen years later, Hagen finally retired from the team’s head coach position, leaving a wave of accolades behind him. Many come in the form of pupils turned pros, but another medal of honor is how he helped Durango host the 2009 Singlespeed World Championship (SSWC).

As the course director of what Hagen described as the “biggest cycling party Durango has ever had,” the Durango SSWC brought 1,200 singlespeed cyclists who raced 20 miles of hilly trails.

“It was brutal, it was hard,” Hagen said. “An insane amount of climbing.”

But what Hagen remembers most about the event is what Durango is often known for: “just all sorts of shenanigans.”

Singlespeed World Championship races are synonymous with counterculture energy, and even the process of vying for a chance to host it is off-kilter. But Durango knows how to throw a party, and there’s no shortage of people willing to perform the various tomfoolery required to be considered for the event. One of those people is Chad Cheeney.

Cheeney, a longtime Durango resident, can be blamed for many things—the list is long—but perhaps the most infamous is his involvement in bringing the SSWC to town.

The process started at the 2008 race in Napa, California, when a group from Durango, including Cheeney, attended in hopes of fighting for the right to host the next edition.

“At first they didn’t like us because we were too braggadocious,” Cheeney said.

The Durango gang got what they came for, but they didn’t win the rights through anything resembling formal means. Instead, they won by playing a game of Miss Pac-man and then going bowling.

“I was on a bowling team in high school, so I crushed it,” Cheeney said.

So, in 2009, Hagen, Cheeney, and a handful of others organized what they hoped would be a pinnacle social gathering race in Durango. And, boy, did they deliver. The parties lasted all week, all through the nights. There was live music at many of the courses’ trailheads and enough beer to keep everyone dancing for days. It was a crown jewel moment for Durango, but a question loomed.

“What do we do now?” Cheeney said, recalling a moment of confusion after the singlespeed party was over.

For Cheeney, the answer has come through years of keeping fun a priority. He’s known for throwing underground, unsanctioned events with debatable legality—zany bike polo games, urban races, heinously gnarly downhill races, and even a bike tossing competition. All gatherings share a common theme of happy cyclists supporting him in his hijinks. Most end with music and dancing.

These days he keeps things a tad more professional. He’s the cofounder of a nonprofit mountain bike coaching program, Durango Devo, and the current head coach of Fort Lewis College’s cycling team.

Durango Devo, developed in 2006 in tandem with fellow local Sarah Tescher, has grown to include more than 600 mountain bike students and 100 coaches. The non-profit’s mission is to develop a lifelong love for mountain biking with kids ranging from toddlers to high schoolers. And while the program doesn’t specifically train for racing, it’s impossible to ignore that many of the program’s alums have gone on to become Olympians, World Tour pros, Grand Tour stage winners, Cape Epic champions, and world and national championship medalists.

Durango’s intermingling party and cycling culture runs deep, but it wouldn’t exist without a goldmine of trails in its backyard. For riders who want to get away from it all, nearby mid and high-country is where the region truly comes alive.

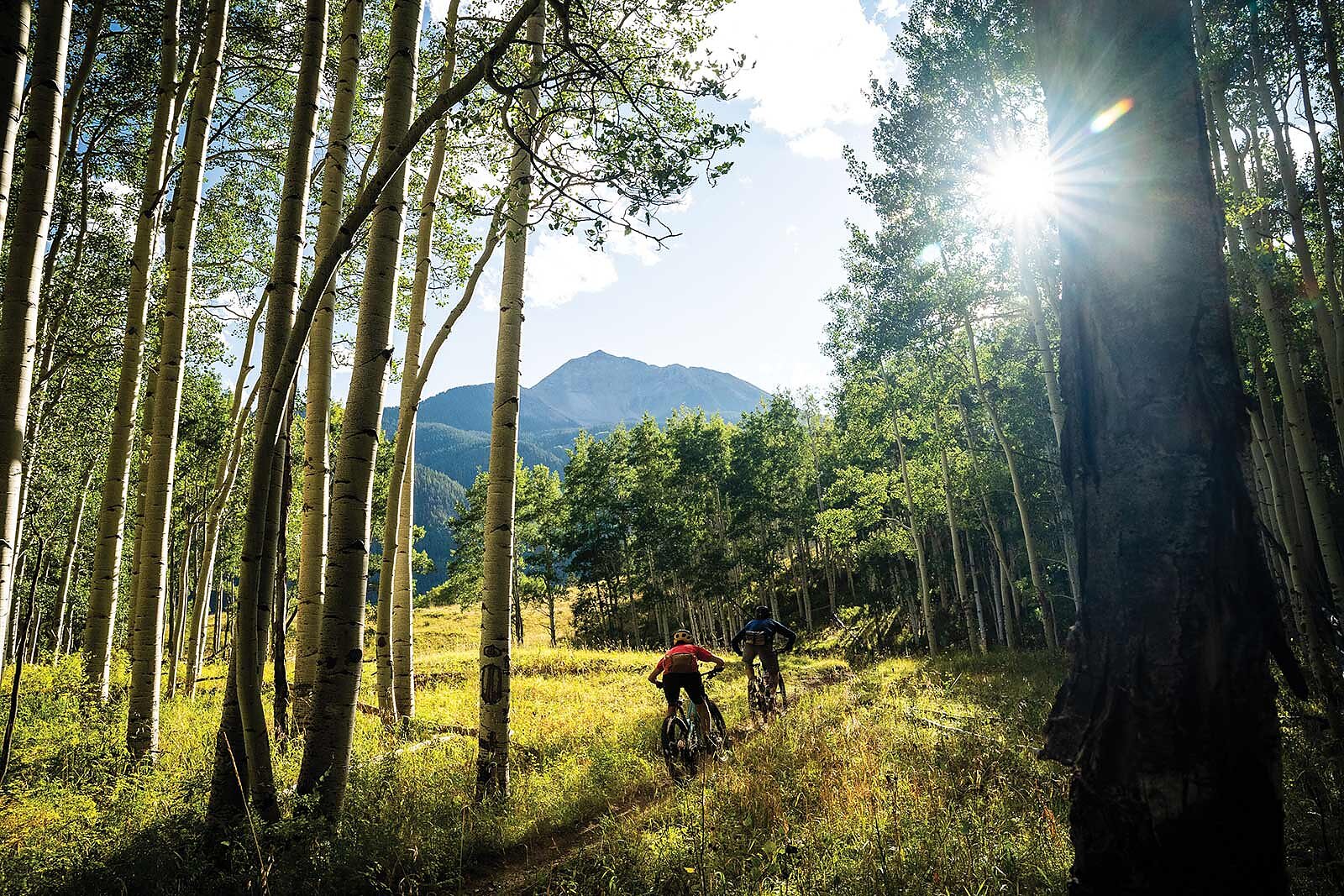

Ten miles north of downtown, quiet trails snake through aspen groves, pine trees, and babbling brooks. Here, the trails are loamy and imprinted with the occasional cow track. Further north, about 20 or 30 miles, is home to some of Colorado’s finest high-country riding. The Colorado Trail, which spans 567 miles in total, passes through this area and is considered by some discerning riders to be the best and most scenic part of the entire route.

Heading south on the Colorado Trail at Molas Pass, back toward Durango, equates to roughly 74 miles of rugged trail. It’s a route that can be taken all the way back to town, or done as an out-and-back.

At Coal Bank Pass, between Molas Pass and Durango, trail options expand further. Various loops, both human-powered and shuttle-assisted, make this a hot zone for local riders. The Pass Creek Trail, also in the area north of town, is a short but steep, well-maintained trail known as a “highway to the high-country” for its direct ascent. The trail begins at 10,600 feet and, in a little over two miles climbs 1,000 feet to the base of Engineer Mountain. The trail then splits and provides a variety of other options; head north and find a few shorter loop routes that head back down to the highway. Or up the total mile-age by going around Engineer Mountain and making a lollipop loop with the Colorado Trail.

Further south on U.S. Highway 550 from the Pass Creek trailhead is Purgatory Resort, home to the area’s bike park. The park is relatively small but offers a range of downhill tracks including jump lines, flow trails and some techy, rooty bits.

Those who prefer backcountry over bike park can keep riding past the resort and up the long U.S. Forest Service road climb that meanders toward Hermosa Creek.

From here, a popular option is the Blackhawk Loop— 26 miles with a high point of nearly 12,000 feet. Shorter loops riding from Hermosa Park Road and Hotel Draw Road are both doubletrack with minimal traffic but plenty of elevation gain. At the spine, where the Colorado Trail starts weaving in and out, is the option to drop east down to the tiny mining town of Rico.

Though it’s just over the mountain range, Rico is two hours by car from Durango, but only 27 miles from Telluride. It’s a place where the locals will know if you’re not from around there. With a bike in tow, they’ll recognize why you’re there. More than likely, they’ll be happy to see you.

At least that’s how the Rico Trails Alliance (RTA) sees it. Relatively new to trail advocacy, the RTA officially formed in 2017 to build and maintain trails but also to acquire newly needed funding. Changes by the Forest Service to a new travel management plan diminished off-highway vehicle riding and, consequentially, the OHV money that was previously used for trail cleanup. So, the RTA was formed in hopes of bringing in more money by promoting recreation to the public.

That backfired in 2020 and 2021 when influxes of COVID-19 recreators began to take over the town and trails. Now, the trail association has shifted focus from promoting their trails to educating users about responsibility and stewardship.

“We dialed down the tourism aspect a little bit and have just focused on taking care of the trails that we already have with our community in mind,” Cristal Hibbard said, an RTA board member.

Rico’s trails aren’t for everyone. Many follow original mining paths, meaning they’re steep and don’t utilize many switchbacks. For advanced riders, that’s fine. For others, Telluride is just up the road.

A handful of gems exist in Rico—they’re almost all blisteringly fast and narrow—but no other trail garners as much attention as Salt Creek. This notorious descent begins at 10,700 feet and descends 5.2 miles to 8,400 feet, cutting through thick stands of aspens that turn fireball yellow during fall. So long as it’s dry, Salt Creek is probably running primo.

Residents of Rico take great pride in their trails, which is why they have vocalized their messages of stewardship and partnered up with their close neighbors to the south, the Southwest Colorado Cycling Association (SWCCA).

The SWCCA, a nonprofit, educates the public on trail upkeep and holds frequent volunteer workdays to keep the region’s singletrack in top shape and sustainable for years to come. The SWCCA has worked to build and maintain trails such as Boggy Draw in Dolores, Sand Canyon west of Cortez, and the notorious Phil’s World network just north of Cortez.

Phil’s World is appropriately named; the first turns were built by a beloved man named Phil Vigil. Riding there can feel like a whole other world—it’s far enough away from the mountains (45 miles west of Durango) to be desert and its flowy 67 miles of trails are known for their many stacked loops, rollercoaster ups and downs, and safari-like sandy curves.

Like Horse Gulch in Durango, Phil’s World also used to be a popular dumping ground and place to shoot guns at cans. As the trail system developed, fights with local property owners who were less excited about the idea of a bicycle playground played out. Then a battle ensued over whether motorized vehicles would be allowed there. The SWCCA eventually formed in the early aughts and took on the duty of leasing the land, cleaning it up, and continuing the legacy of Phil and his playful trailbuilding style.

It’s a common theme in the vast open lands of this far corner of Colorado—mountain bikers are emerging as those hardy and fit enough to enjoy the rugged country while also harboring the passion and desire to preserve and maintain it.