Righteous Goodness Sterling Lorence, a Messiah of Light

Words by Mitchell Scott | Photos by Sterling Lorence

You could suppose that photographers are artists at their soul.

That they’re master technicians, the camera a second extension of themselves. Or that they’re messiahs of light and how to capture it. And I could never answer those questions. I’m not a photographer. Just a friend. All I know is the story of how a kid who loved his backyard ended up creating a career whereby he could share it with the world.

The story starts some four decades ago. Sterling Lorence and I were lucky little buggers. His house was spectacularly positioned at the confl uence of a creek and the ocean. I lived just up the street. We were groms in paradise, and we knew it. We’d fish for flounders in our little dingies and have rock fights on the beach. We lived on a circular road with little traffic and lots of kids, and from our earliest memories, we were riding bikes, exploring, and in the rare event we got bored, causing trouble. It was the late ’70s and early ’80s in West Vancouver, British Columbia, what is today one of the richest communities in Canada. Back then, though, it felt like we were living in the backwater.

I remember Sterl being especially drawn to Cypress Creek. He could practically see it from his bedroom window. The creek was an entity unto itself. In the winter it would pound with huge chocolate flow, full of debris and thunder. In the summer, a trickle of crystal clear mountain water. From Sterl’s house, when the water was low, we’d often clamber up the waterway. It would soon turn into narrow canyons and pools, then waterfalls and cliffs. Every year, as we grew older and braver, we’d venture farther up the creek, until we found ourselves in the heart of coastal old-growth forest. Trees hundreds of years old, draped with mosses and mist, under columns of rare light navigating its complex canopy, giant ferns and salal. Often, when the creek canyon became too steep and dangerous, we would clamber onto its upper banks. It’s here we found our first trails.

By now it was the mid ’80s and my dad got a Miyata Ridge Runner from the Deep Cove Bike Shop. It was one of the first mountain bikes in West Van. We were astounded, blown away, we had to have one. So we hunkered down on paper routes, saved our dollars and bought our first real mountain bikes. Not surprisingly, we went straight to those trails.

“My parents let us roam in free time,” Sterling says. “Just be home for lunch or dinner. For fun we simply went outside and explored the creek and the beach tideline. Never did it not captivate me. I loved hiking up the creek, into its canyons, beneath the forest. It was raw and pure, dangerous and inspirational. That mood in nature is why I fell in love with mountain biking. We could roam in the woods and get a thrill, too. All those inspirations and moods and feelings are the foundation of what

I most love to shoot.”

We threw ourselves into the sport. The shitty V-brakes couldn’t stop us, the toe-clips couldn’t kill us, the lack of suspension and the roots and the rocks would break us, and our bikes, but we always bounced back. We were so hooked. We couldn’t stop, and after a decade of Fleshy Wounds and Reapers and Boogeymans, we knew we were part of something special: The Shore. I started writing about it, our best friend Andrew Shandro started really shredding it, and Sterl began to shoot it. His first-ever published shot in Bike magazine was a small inset of a trail sign in my first-ever feature on anything: May 1998’s “Fear and Loaming.” We were in.

Fast forward to today, and Sterl has more covers of Bike than any other photographer, more than 30. Throughout his 20-year career, he’s had hundreds of shots published in that one magazine alone. Which is no small feat. Bike’s founding photo editor, Dave Reddick, was a gatekeeper of the highest order. Only the best of the best made it into his pages. And, according to Reddick, Sterl is just that: the best of the best.

"He doesn’t go out and snap a bunch of photos, he’ll circumnavigate a zone, he’ll spend hours trying to find the best possible options, investigating all of the angles. It’s a very technical approach to each photo."—David Reddick

“When I think of Sterl’s work,” Reddick says, “well, it’s pristine. It has evolved to a level of pure quality. Nothing is out of place. He considers it. He doesn’t go out and snap a bunch of photos, he’ll circumnavigate a zone, he’ll spend hours trying to find the best possible options, investigating all of the angles. It’s a very technical approach to each photo. He’s also a woodland creature, which I think helps.”

It was a relationship that would define Sterl’s career, and at the same time, the editorial legitimacy of Bike magazine as the true voice for mountain biking’s fast-paced explosion onto the world stage. Through the Shore to the birth of Freeride, Sterl was at the forefront of its documentation. His photos told stories, they introduced new riders to the fray, they captured monumental moments of a sport stepping into new territory. All on the printed page.

“I believe that Dave Reddick has had one of the largest influences in the quality of ski and cycling photography in the past 25 years,” Sterling says. “His eye as editor set a standard that elevated what was capable. He saw that style, that light, that creative angle or special life moment and thus shaped how we should strive for it. Powder and Bike became the industry apex for photography and any serious photogs who wanted to be part of it. We all raised the bar together. The impact will be felt for decades through photos and filmmaking. Dave is one of the key figures in the shaping and success of my photography career.”

But while Bike magazine has played a formidable role in Sterl’s success, his body of work is massive. However, even though he’s stepped out into the world of commercial photography and other sports, his true passion, and the body of his business, rests in mountain biking. A sport he has, for all intents and purposes, dedicated his life to. Sterl is an incredible rider. He’s fit, can climb like a banshee and, from a lifetime of riding his backyard (he still lives with his wife and two young daughters in West Vancouver), is an incredibly skilled technical descender. He knows what good riding looks like because he knows how to do it. It’s been a huge part of his success with his photography, and a real driver too. He pushes his riders hard because he knows what’s on the line—not just a published photo, but the progression of the sport itself.

“I think one thing that makes Sterl unique is his ability to get the best out of an athlete,” Thomas Vanderham says. “Being a strong rider himself, Sterl has a very good understanding of the sport, which helps him as a photographer. He’s hypersensitive to style, and on any given shot he is constantly communicating with the athletes to sync his angle with their best moment of action.”

And while Sterl has worked with the best of the best—Stevie Smith, John Tomac, Ned Overend, Gary Fisher, Ryder Hesjedal, Wade Simmons, Greg Minnaar, Steve Peat, Cam McCaul, Cedric Gracia, Matt Hunter, Andrew Shandro, Thomas Vanderham, Graham Agassiz, Darren Berrecloth, Brett Rheeder, Brandon Semenuk, Tomas Genon, Aaron Gwin, Alison Sydor, Brett Tippie and Hans Rey to name but a few—the background and technicality of Sterling’s shots, the light, the composition, the exposure, are, for lack of a better word, exquisite. I remember one of our first big feature assignments together for Bike a number of years ago. We were on a dream trip in the Valais region of Switzerland. It was Chris Winter’s first Big Mountain trip ever, and we were there, with Shandro, Simmons and a crew of Whistler riders. Every day we’d be using gondolas to access new terrain, staying in little mountaintop refugios, eating raclette and drinking white wine (Shandro’s farts were insane).

We were on the move constantly. As the writer, the story was so rich, so diverse, so adventurous. But on day two Sterl was not stoked. “I feel like I’m in the biggest candy store in the world and all I get to have is the odd jelly bean,” he said to me, complaining that we were travelling through these epic landscapes at the wrong time of day, without the ability for him to adequately scope his shots, or wait for good light. I retorted as only good friends can, “Suck it up bro, this is the best story of my career, be a photojournalist, document the adventure, every shot doesn’t need to be a cover.”

Of course, Sterl wouldn’t have any of it. After our seven-day trip was over, he convinced Wade and Shandro to stay an extra three days. They rented a car and went back to tag some of his favorite locations in early morning and sunset light. He didn’t care if Reddick wouldn’t cover the extra cost. “I’ll pay for it myself!” I remember him saying. Not surprisingly, one photo from that shoot made the cover, others graced the gallery, and the rest took the feature over the top. It was classic Sterl.

“He doesn’t leave a stone unturned,” says Haruki Noguchi, a former North Shore-based photographer. “If he’s going to shoot somewhere, he’s going to do 360s with all of his lenses to ensure he’s got the right angle. I don’t know guys who spend three or four days just to watch a trail in different light. He’s super invested. And he does it every time.”

Sterl has an innate ability to see the kooks, and is not afraid to let them know it. This is mountain biking, after all. We’re here to work, to make magic happen, and if we’re blowing it, if we’re not doing it right, if we’re not trying hard enough, if we’re faking it, you’re going to hear about it.

That passion for the sport, love of the landscape and relentless perfectionism (which can be a bit of a bitch to work with, to be totally honest), is the defining recipe of perhaps the most published and recognizable photographer in the history of mountain biking. He’s worked with Trek, Giant, Specialized, Shimano, Easton/Raceface, and Rocky Mountain, and brands like Tourism British Columbia, the Vancouver Canucks, Toyota, BMW, Microsoft, Burger King, Abus, Pepsi, Subaru—even the Olympic Games. Along with covering most of Canada and the United States, he’s shot in Mexico, Chile, New Zealand, Indonesia, Thailand, Nepal, India, Japan, Iceland, Greenland, Scotland, Romania, Austria, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, France, Spain, Portugal, Morocco, Reunion Island, Fiji and South Africa. It’s been a hallowed, fun, hardworking, fascinating and deeply rewarding career. Not just for Sterling himself, but for anyone who’s had the opportunity to see one of his photos.

For those who’ve had the great opportunity to see him on the other side of the lens, in the field, well, that’s equally as much of a joy. Sterl is a quirky fellow. He’s got a dry, lightning-quick sense of humor about him, and a disposition where, if he knows you, he’s definitely not afraid to give you the business. Sterl has an innate ability to see the kooks, and is not afraid to let them know it. This is mountain biking, after all. We’re here to work, to make magic happen, and if we’re blowing it, if we’re not doing it right, if we’re not trying hard enough, if we’re faking it, you’re going to hear about it.

“Sterl has a relentless work ethic, which might be putting it lightly,” Vanderham says. “I’ve been on long trips with him where the crew is winding down toward the end of the shoot, everyone is feeling good about the imagery that we’ve got in the can, and Sterl is still chomping at the bit like it’s our first day there and we haven’t shot a photo yet. You can bet if there is one last sunrise that we will be getting up at the crack of dawn to shoot it. It’s impressive and exhausting.”

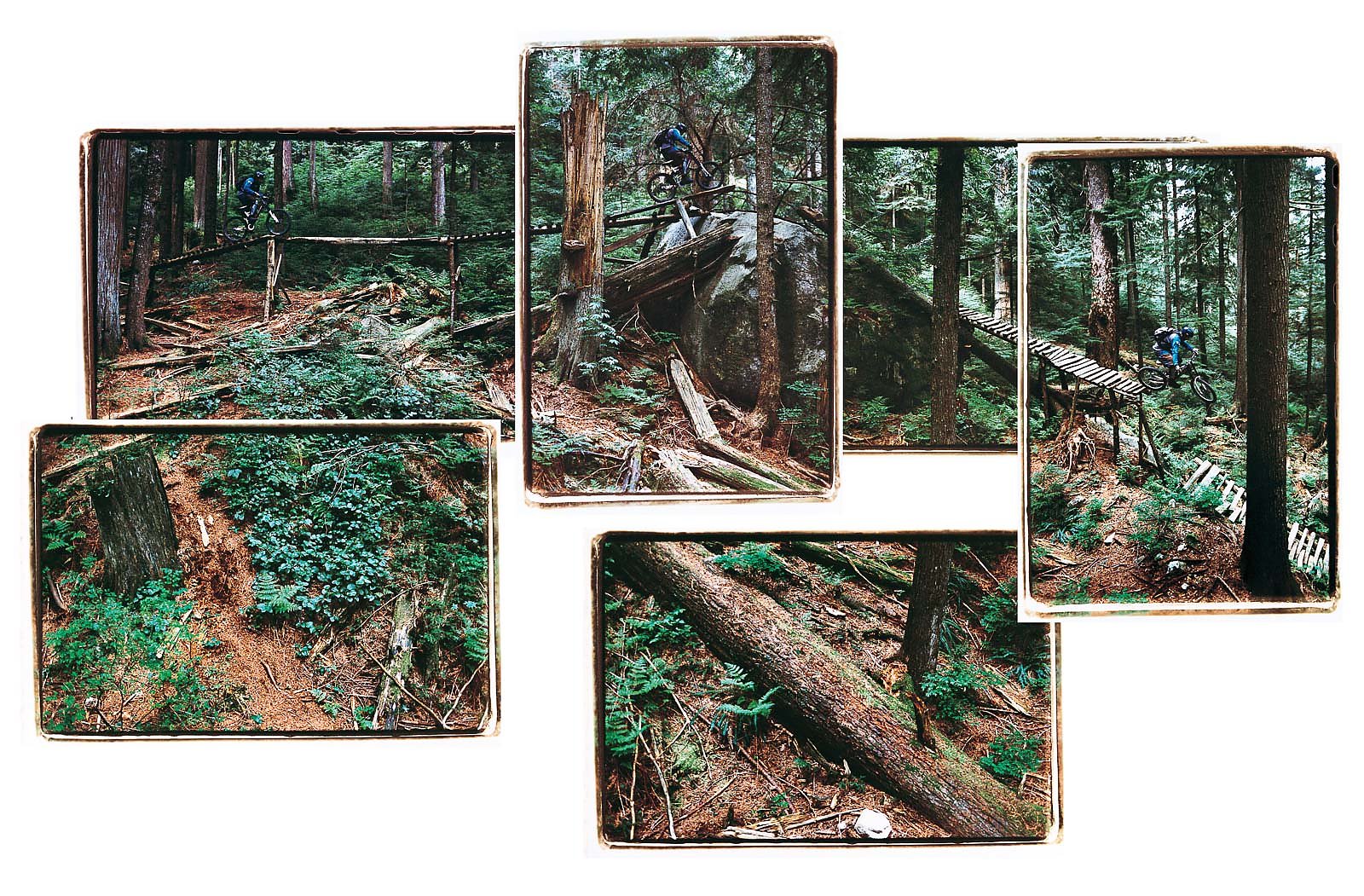

The memories are making me chuckle, and a little nostalgic. I often think back to those early days. Led by Sterl, our crew built a monumental trail on Cypress Mountain that we kept secret for years. We had to bushwhack-sneak to its entrance, and we painted the stunts camouflage to hide them from the air. It was an all-day epic ride with rope-assisted ravine crossings that took us four years to build. He named it Sagarmatha, the Sherpa name for Everest.

More than any of us, Sterl loved it up there. He loved the mist and the ravens, the old growth “hawgs” as he calls them, and everything about friends on adventures in our own backyard. It’s why we all never really grew up, and why we still ride our little fannies off to this day. It’s the nature side of nurture, and if there’s one thing we could say inspired Sterl and his amazing talents, it’s the forests above West Vancouver.

“In a nutshell, I became a pro photographer because I was in the right place at the right time,” Sterling says. “I was a mountain biker in love with the sport and with riding on the North Shore as a kid with my friends...the Shore and BC were firing with the push of real mountain biking and freeriding and the world started to be curious, amazed and wanting it. Mitch as my friend and a writer was typing the story, and photo opportunities to editorial and commercial came calling. The phone was ringing and now 20 years has passed in the blink of an eye.”

Sterl could have been anything. I know he had some pressure to get into the real estate game when he was younger, his dad, mom and brother all work in the industry and are quite successful. He could have gotten sucked into other elements of business, like so many of our friends did along the way. Photography is a hard job, with lots of time away, huge days, big packs, the woes of Instagram, the death of magazines, the scourge of the iPhone and the general devaluing of the almighty image. But Sterl never lost sight of his vision. He made a commitment, he crafted his style, never gave up, worked his ass off, continues to work his ass off and, ultimately, he cares.

And perhaps this is the most critical element of his career, the caring part. Not necessarily caring about just him, but all the elements he’s trying to capture: the sport, the landscape, the rider, the moment, the story. It is, from my perspective, true day in, day out altruism. It’s a rare quality these days. Thank the good lord my man Sterl wields it like a mighty oldgrowth staff of righteous goodness. Because I guarantee this: The world is less beautiful without it.

![“Brett Rheeder’s front flip off the start drop at Crankworx in 2019 was sure impressive but also a lead up to a first-ever windshield wiper in competition,” said photographer Paris Gore. “Although Emil [Johansson] took the win, Brett was on a roll of a year and took the overall FMB World Championship win. I just remember at the time some of these tricks were still so new to competition—it was mind-blowing to witness.” Photo: Paris Gore | 2019](https://freehub.com/sites/freehub/files/styles/grid_teaser/public/articles/Decades_in_the_Making_Opener.jpg)