The Pursuit of the Unpaved The Remote Roots of Arkansas Mountain Biking

Words by Matt Porter

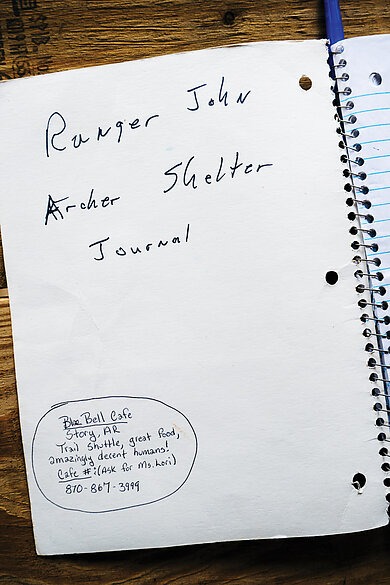

Before GPS devices, well-marked trail networks, and Google Maps, the paper map and word-of-mouth were the only navigation tools. Many available maps had limited information—some having had their last update around the time your dad drove that 1982 Datsun pickup out to see the sunset on some remote road.

During this era, mountain bikes consisted of rim brakes, 26-inch wheels, and a heavy steel frame with a rigid fork. Rear suspension may as well have been science fiction. Instead, sheer will and determination fueled riders eager to explore paths less trodden. These early mountain bikers rode to avoid pavement at all costs; this is the history of backcountry riding in the state of Arkansas, just as it was in most places across the United States.

In fact, backcountry mountain biking was part of the Arkansas riding scene long before the explosion of its self-proclaimed “Mountain Biking Capital of the World” trail hub in Bentonville.

Arkansas has 173,000 miles of rural roads. More than 60,000 miles of them are unpaved. The history of remote riding in the Natural State is woven into these roads—many of which still don’t appear on maps—that lead adventurous souls to epic vistas and beauty only accessible through effort and determination.

“We can just ride the damn dirt and see how far we can go,” said Pat Zimmerman, a long-time Arkansas rider, of his mentality back in those early days of the sport.

His escapades often led him on exploratory missions through country not accustomed to seeing cyclists. One such trip in 1996 somewhere south of Winslow, Arkansas proved particularly memorable. Zimmerman and friends were riding down Interstate 49 before it was paved, had bridges, or was open to vehicle traffic.

“We ran out of water, ran out of food, we were lost as hell,” Zimmerman said about one such adventure. “We [were] probably six hours in.”

After bombing through a field, Zimmerman and his buddies passed a farmhouse hoping to find a road. As they flew by, they saw a man watching them from a doorway. Soon they were back on gravel and feeling better about where they were.

“We go about a mile and there is a family reunion going on—I mean we are in rural Arkansas, and they look at us like ‘Where did y’all come from?’” Zimmerman said. The group was shocked when he told them he’d come from their neighbor’s back pasture.

“You’re lucky you didn’t get shot,” they told Zimmerman. “He is crazy.”

Two main mountain ranges, the Ouachitas and the Ozarks, rise from the otherwise flat landscape that defines most of Arkansas’ geography. The Ozarks are a series of rocky plateaus that run south out of Missouri. Their rugged landscape consists of caves, springs, and countless other geological features. In contrast, the Ouachita range runs east to west, with large lakes in the valleys, hardwood forests on its north-facing slopes, and pine and oak forests on southern slopes.

The Ouachitas are known for their rugged and remote nature. This range was used by outlaws and bandits trying to escape the law in the late 1800s, creating such legends as Isaac Charles Parker, also known as “Hanging Judge Parker,” for his ruthlessness when captured outlaws were brought to justice in his courtroom. The book True Grit by Charles Portis was set in the Ouachitas and later depicted in a Hollywood adaptation starring John Wayne.

Before settlers moved into the territory, Indigenous tribes including the Caddo, the Chickasaw, the Osage, and the Choctaw lived in the region. The word “Ouachita,” is a French derivative of the native word “Washita,” which loosely translates to “good hunting grounds.”

“If you look at a topo map, the Ozarks are like crinkled up tinfoil while the Ouachitas are like long snakes,” said Kenny Williams, the creator of the 161-mile Ouachita Triple Crown bikepacking route.

The word “backcountry” is often meant to imply “epic”— at least for mountain bikers. Those who venture into the backcountry seek not just adventure, but the rare opportunity to witness the grandeur and beauty of a landscape that eludes many.

“NONPROFIT GROUPS HAVE REALLY STEPPED UP IN RECENT YEARS TO MAINTAIN THESE TRAILS WITH SHRINKING FOREST SERVICE BUDGETS AND RESOURCES BEING SHIFTED TO ADDRESS LARGE SCALE FOREST FIRES OUT WEST.”—Mitchell Allen

“Backcountry riding is always an unchoreographed adventure—it is raw, it is wild, it requires full engagement, it is a sense of facing the unknown,” said Johnny Brazil, owner of Jackalope Cycling, a community bike shop in Russellville near the Ouachita Mountains and a few trails designated as “Epic” by the International Mountain Bicycling Association (IMBA). To earn this badge, routes must be majority singletrack and at least 20 miles in distance. Not for the faint of heart, these routes are challenging, but the reward is measured in stories and perspectives shifted by the impact of land and the beauty of the places visited.

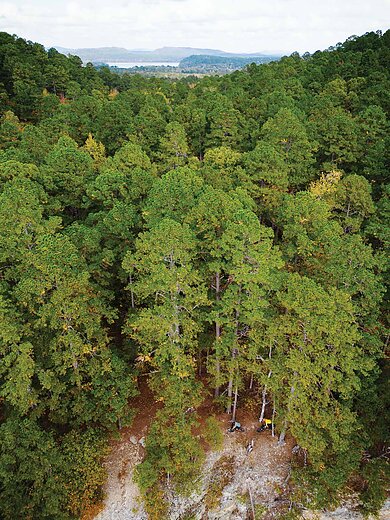

The first trail in Arkansas to receive the IMBA Epic distinction was the Womble, located at the midpoint between Mount Ida and Mount Oden in the central west part of the state. Built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s, the trail is now maintained by volunteers from organizations such as Mountain Bike Arkansas and the U.S. Forest Service. The Womble is a point-to-point trail traversing 37 miles of mostly singletrack riding with areas of extreme exposure. The surrounding forest is made up of a mixture of hardwood and pine trees that cling to exposed ridges offering expansive views of the Ouachita River below.

“You definitely realize which side you are comfortable with exposure on,” Brazil said with a laugh, part sinister and part nervous. In some areas, the trail narrows to 16-inchwide benchcut. Here, the margin for error is small.

Still, the Womble trail is mostly ridable. The Ouachita National Recreation (OT) trail, on the other hand, is described as true “old school gnar” by Williams. Totaling 223 miles across National Forest and State Park land—108 of which are open to mountain bikes—the OT is the longest Epic in Arkansas. It was granted this status in 2015, 25 years after it was first opened to mountain bikers. Similar to the Womble, the OT was built in the 1930s and ‘40s by the Works Progress Administration, a federal initiative that focused on providing jobs for Americans during the Great Depression by way of public service projects. The trail cuts through some of the most remote parts of Arkansas—many sections are miles from the nearest paved road and do not have cell service.

While the secluded nature of the trail leads to an authentic backcountry riding experience, it also equates to a lack of ridership, says Brazil. This, it turns out, is one of the downsides to its remoteness. A lack of consistent traffic on these trails—at least compared to modern trails closer to population centers—leads to overgrowth, making trail maintenance a never-ending task that, if not addressed, can diminish eventual trail users’ experience. Despite the challenge, local groups are stepping in where needed to keep Arkansas’ backcountry trails alive.

“Nonprofit groups have really stepped up in recent years to maintain these trails with shrinking Forest Service budgets and resources being shifted to address large scale forest fires out West,” said Mitchell Allen, the interim executive director of the Arkansas Parks and Recreation Foundation. Recently, the Foundation was awarded a $120,000 grant by the Arkansas Department of Transportation to maintain singletrack and other soft surface trails in the state.

“My goal for riders that come to ride the Epics is that they have a good experience on a well-maintained trail,” Allen said. “They will in turn support wild spaces and public lands, and they will realize why these places are important both personally and more broadly to the world we live in.”

To the south and across Lake Ouachita from where the OT passes through, the Lake Ouachita Vista Trail, affectionately referred to as the LOViT trail, offers a less extreme long ride experience at 38 miles with 3,600 feet of elevation gain. It is considered the most approachable of the three IMBA Epics in the Ouachita range. Built by the Civil Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Forest Service, and countless volunteers, many working under the Traildogs moniker, the LOViT was completed in 2014. With a mission to create recreational opportunities during the shoulder seasons when lake activities declined, the LOViT winds its way up to reveal expansive vistas of Lake Ouachita and its surrounding peaks. After double-digit grade climbs from the east and west, the eastern section rewards riders with a long ridge ride.

“We rode from Blakely Dam to the top of Brady Mountain and had 1,500 feet of vert in something like three to five miles,” Brazil said. He describes the climb to the top of the ridge and the ridgeline itself as “super fun” with a few gnarly sections.

Trails in the Ouachita Mountains, like the Womble, the LOViT, and the OT were early IMBA Epic trails in the state and were originally constructed for hiking purposes. Then, after local groups and individuals advocated for bike use, they were opened to mountain bikers. In total, Arkansas has five Epics, including these three, the Upper Buffalo Headwaters, and the Syllamo trail system located in the more well-known Ozark mountain range.

These types of long-distance, rugged trails stand in stark contrast to the boom of modern flow trails popping up all over the state. As the distance from home to trail shrinks for an increasing number of Arkansas mountain bikers, some wonder whether its Epics and other further afield singletrack will continue to see strong use. Some upcoming trail projects, and the continued success of long-distance race events, provide a bright glimmer of hope.

In Mena, a small city in far west Arkansas, new backcountry trails and land access are expanding with the Trails at Mena Project, a collaboration between Arkansas State Parks, Arkansas Parks and Recreation Foundation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the City of Mena. Initial plans for the project outline miles of newly planned trails, some of which may eventually be accessible by chairlifts.

“There are 9,000 acres out there,” Allen said. “You better believe there will be a backcountry element to the Mena project.”

Some veterans of Arkansas’ cycling scene see a future in which long-distance trails will see a resurgence.

“[Riders] will intentionally seek things that are not easy as life becomes more comfortable,” Williams said. The annual Arkansas High Country Race in October now offers the Triple Crown route as an option. This opportunity to race fully self-supported adds an extra layer of challenge and continues to draw riders from all over the country. In this new era of mountain biking that has provided abundant access and manicured trails with few obstacles, Williams believes there is still a place in the sport wherein “the trail is not changed to be exactly what a mountain biker wants.”

In 2017, when Williams was designing the Triple Crown route, he said it practically connected itself. Linking the Womble, LOViT, and Ouachita National Recreation Trail, the 161-mile route gains 16,000 feet of elevation, 90% of which is on dirt, with 66% of that on singletrack. The journey varies in difficulty and feeling with the Womble portion described by Williams as “tucked in, old school flow trail,” and the OT section providing a counterpoint of “old school miserable gnar.”

“Outside of a couple gnarly punchy baby head climbs, the LOViT is this amazing ridgetop panorama for hours— the views you get on the LOViT, you cannot get from a car,” Williams said. “[Riding helps us] remember our own grit, resilience, toughness—that I don’t need to remove every discomfort and every barrier, that I can do hard things. These are important characteristics to be able to hold onto when you go back to your daily life.”

George Chevalier, a promotions manager at IMBA, sees Epic-designated trails as a natural evolution for mountain bikers looking to graduate from their close-to-home trails and step out of their comfort zone.

“They [Epics] give riders something to reach for, something to prepare and train for,” Chevalier said. “When it comes to backcountry riding ... it was not that approachable for newer riders. We [IMBA] are trying to build on-ramps that lead to progression in riding opportunities.”

While trail organizations and veteran riders such as IMBA and Williams hope to continue to attract new riders to Arkansas’ plethora of less traveled singletrack, plenty of locals are already reaping the benefits from them and working the routes into their regular routines. Brazil, for one, has had some of his most memorable moments on a bike on chunky sections of remote trail. Once, together with a friend on the LOViT, bike, trail, the environment, and time seemed to blend.

“The fall colors were hitting just right, I couldn’t hear cars, the lake was on our right, and the stretch of singletrack laid out in front of us was just flowing by,” Brazil said. “We were both hooting and hollering at each other. Everything was gone except that moment.”