For the Love of Speed The Ingenious Mind of Mert Lawwill

Words by Jann Eberharter

Mert Lawwill never really rode mountain bikes.

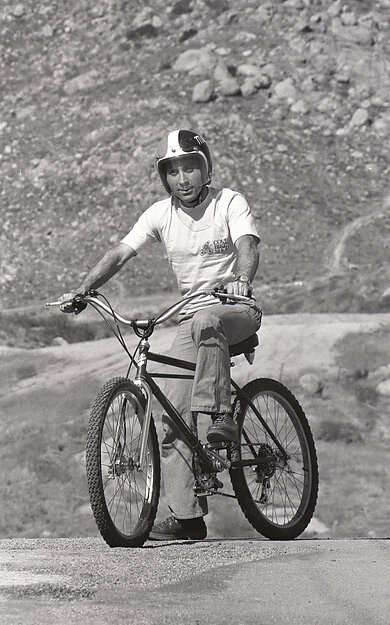

Perhaps this is because he was more used to doing 100 miles per hour on his motorcycle while racing flat track—the literal and historic definition of “foot-out, flat-out.” When that’s normal, riding something with pedals instead of a motor could understandably be boring.

The man is a living legend when it comes to motorcycles. He was at the pinnacle of his career in the late 1960s and won the American Motorcyclist Association Grand National Championship in 1969. The following year, he filmed for Bruce Brown’s documentary On Any Sunday. When it debuted in 1971, Mert was catapulted from a god among men on the racetrack to an American icon on the silver screen, right next to Steve McQueen.

But throughout his illustrious racing career, Mert also experimented in the then-burgeoning world of mountain bikes. Not as a rider, although he’d occasionally point one down the hill, but as a frame designer and suspension engineer. He’s someone who can’t help but look at something and think about how it works—and how it could work better. He also happened to have unparalleled knowledge and experience in the realm where physics and two wheels collide.

Living in Marin County, California, often celebrated as the de facto birthplace of mountain biking (although Mert might argue otherwise), it was inevitable that Mert’s path would cross with the vanguard of this rapidly developing yet technologically suppressed two-wheeled sport. And when it did, there would be no turning back. Through his love for tinkering, a handful of business ventures, a son who was dedicated to racing motocross, and his obsession with speed, mountain bikes would be forever changed.

HARLEY-DAVIDSON XR-750

There was no indoor bathroom at the Lawwill family residence until Mert was a teenager. Born in 1940 in Boise, Idaho, he was one of seven kids. The family lived on eight acres, and as a child growing up through the recovery of World War II, with parents who had grown up during the Great Depression, luxuries were minimal. But that didn’t stop Mert and his siblings. They’d do chores, tend the garden and play outside, perfectly content.

Then one day his brother came home with a Corgi; a British-made, 98cc folding scooter that was designed to be tossed out of airplanes for military use. It was the first combustion bike Mert ever rode and from that day on, he was transfixed.

“Everybody in my family, they were all achievers,” Mert says. “They could all play musical instruments, or they were artists—except me. I couldn’t do very much. I tried to play the clarinet for five years, but… I just had interest in wheels.”

Following this calling, at the age of 21 he moved to Los Angeles, home of the famed Ascot Park speedway. At the time, Southern California had motorhead energy that rumbled like a Harley-Davidson XR-750 with an 883 Sportster motor, the fuel for which was Ascot. The speedway held motorcycle, sprint car, stock car, dune buggy and Go Kart races among a long list of disciplines. But for any two-wheel fanatic, nothing came close to the Friday night flat-track races.

In the spring, Mert would race at Ascot every Friday night, then come summer he’d pack up and drive east with the rest of the riders. They’d race Wednesday nights in Chicago, Thursdays and Fridays at local fairgrounds, and then compete in the National circuit events on the weekends, driving across the country several times a season. By 1963 he was racing pro, and a year later he signed a contract with the Harley-Davidson factory team.

“After you race three or four times a week, for months on end, you start to get pretty good,” Mert says. “It’s just sort of like if you’re born to do something, you end up doing it.”

Five years later, in 1969, he won the AMA Grand National Championship by accruing points throughout the course of 27 races, earning the prestigious number-one plate for the following season. It was during this time that he was approached by Bruce Brown, the filmmaker who produced the iconic surf film The Endless Summer in 1964, and he told Mert about his plans to make a similar-scale motorcycle flick. He wanted Mert to be one of the main characters. The resulting film, On Any Sunday, documented Mert’s season defending his title and legitimized the era’s racing and riding culture.

“The world met Mert in 1971 when the movie On Any Sunday came out,” says John Parker, co-founder of Yeti Cycles and fellow Ascot Park racer. “Mert was just a Friday night god. This giant of a man—for the movie, for having had the number-one plate, for being a factory Harley-Davidson rider—Mert was just on top of his game. He had the beautiful wife. He had the little kids. Mert had it all going.”

“Mert was just a Friday night god. This giant of a man—for the movie, for having had the number-one plate, for being a factory Harley-Davidson rider—Mert was just on top of his game.”—John Parker

He also had a drive to innovate at every opportunity. Through putting his bikes to the ultimate test on the racetrack, Mert was constantly discovering things that could be improved upon. Unlike a lot of racers who let their mechanics do the greasy work, he did all his own maintenance. It started out with swapping tires and changing oil, but it wasn’t long until he was adjusting frame geometry and engine location and even adding suspension to his flat tracker— something unheard of at the time. Such was his attention to precision that he’d use half-links in his chain to achieve the exact wheelbase he wanted.

Mert’s tinkering and competitiveness went hand-in-hand. He was driven to make his bike better in every capacity and ensure it was all working to his advantage while on the track. There was much to learn and even more to figure out.

“We were making our money racing motorcycles,” Mert says, “so anything you learned, you didn’t tell anybody. Everything was secret.”

Eventually, this led to Mert building frames for the Harley factory, as well as an aftermarket frame he stamped with the Lawwill name. At one point, nearly every flat-track frame in the country was his design. His partner in the process was Terry Knight, a talented welder and fabricator. Serendipitously, Terry was also welding BMX frames at the time and, noticing the sport’s growing popularity, mentioned to Mert it might be an equally lucrative endeavor.

LAWWILL/KNIGHT PRO CRUISER

Inspired by Terry, Mert wanted to see what BMX frames were all about. So, he stopped by Cove Bike Shop, a local retailer in Tiburon, California. Had he walked into any other bike shop in the country, he might have gotten the standard sales pitch. Instead, he met the Koski family who owned Cove and, more importantly, the brothers Donny, Dave and Eric, who essentially ran the place. On the spot, a young Donny showed him his custom-built, five-speed, steel-rimmed bike with motorcycle handlebars and a proprietary fork he’d designed himself.

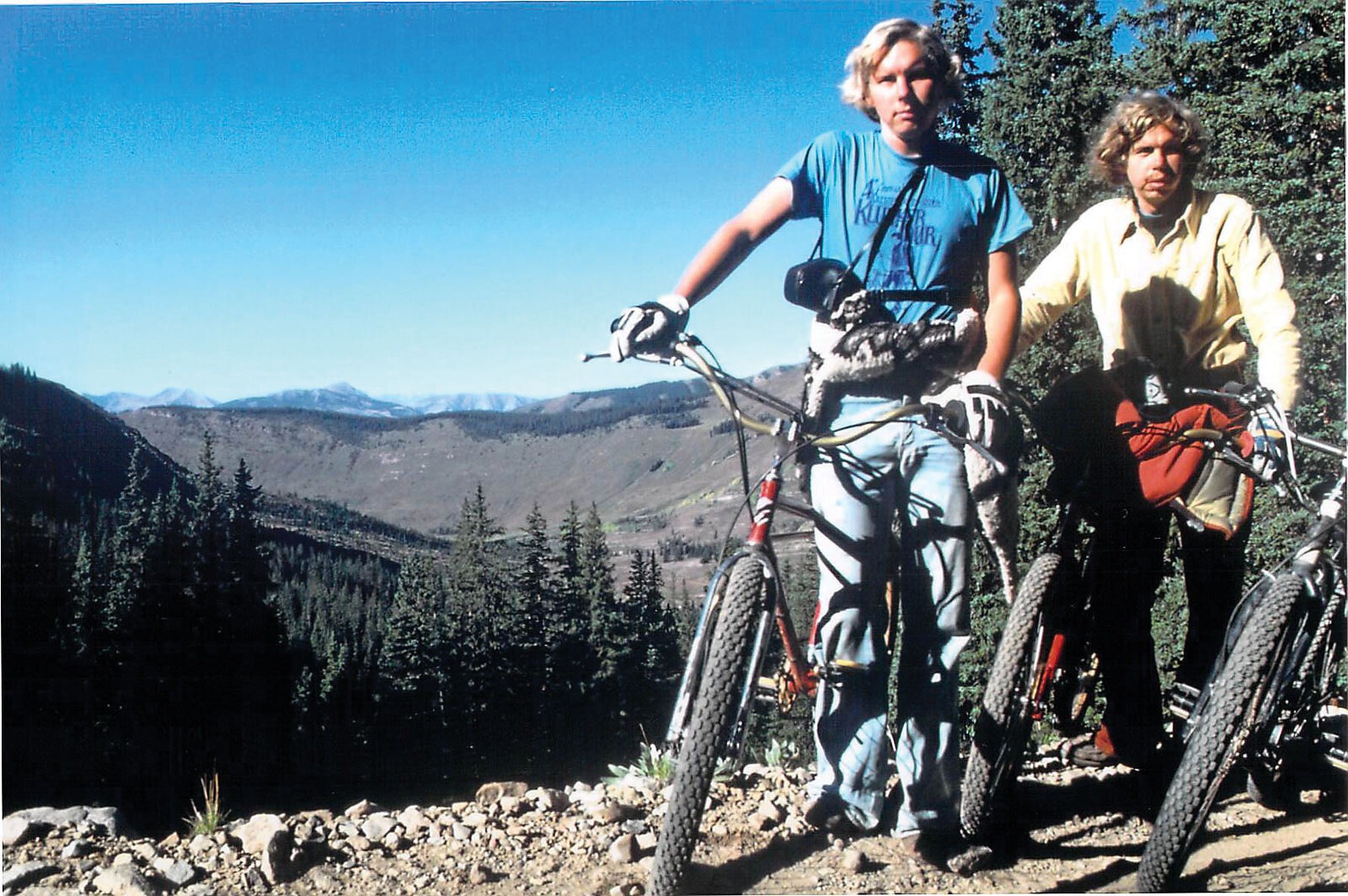

Donny recalls telling Mert that everybody was already making BMX frames, but no one was producing a bike that could withstand the terrain and riding styles that were gaining popularity in Marin. The term “mountain bike” had barely been coined at the time. Guys like Charlie Kelly and Joe Breeze were building their fat-tired bikes, but on a custom basis, and one at a time. So Mert and Terry used Donny’s frame for inspiration, along with some design flair that Terry had taken from his previous gig welding Doug Schwerma’s Champion BMX frames, and created their own.

The first iteration had parallel 69-degree head and seat-tube angles. Coming from flat track, Mert’s goal was to be able to slide around corners so, just as with a motorcycle, the rider’s weight had to be as far back as possible. The bike didn’t pedal very well, so they went back to the drawing board and straightened things out. The next one was more of a compromise.

“The thing was just a downhiller from heaven,” Donny says. “It didn’t climb super good because the seat tube was not as upright as some of the stuff Joe Breeze was building, [but] we just started selling the hell out of the frames.”

It didn’t take long for Mert to decide they should produce a batch of 50 bikes. He originally called it the Lawwill Mountain Bike but, after being told by dealers that “nobody wants to ride a bicycle up a mountain,” renamed it the Pro Cruiser. The bikes sold quickly after that.

GARY FISHER RS-1

Growing up, Joe wanted to forge his own path within the motorcycle world racing motocross. As the son of a motorcycle legend, this career choice was almost expected. But with Mert traveling to his own races all the time as well as the financial burdens that came with being a self-supported motocross racer, Joe struggled to make it as a professional.

As the hotspot of mountain biking, Marin’s riders were growing in numbers, and Joe fell in with friends who were riding on a regular basis. Soon he was taking Mert’s homemade prototype suspension bikes out to ride and test. It became a rhythm of create, break, decipher and fix for Mert, continually operating from Joe’s feedback and working to improve the bikes and the way they rode. By the time the process yielded a groundbreaking bike based on Mert’s four-pivot platform, there was interest from Gary Fisher, a fellow frame designer and mountain bike pioneer. “Gary Fisher is the key,” Joe says. “He’s the guy that says, ‘Mert, I trust you. Let’s do something.’ So, the two of them got together and that’s what eventually turned into the Gary Fisher RS-1 in 1990. That was really the turning point.”

Joe had been pushing Mert to develop his design into something more official, and teaming up with someone as visionary as Gary opened the doors of opportunity. That same year the RS-1 won Bicycling Magazine’s Hot Bike award, and officially went into production in 1991 with 2.5 inches of travel. Through all the testing, Joe had linked up with Myles Rockwell, an exceptionally fast rider who was racing on the National Off Road Bicycle Association circuit. The duo ended up at a local downhill race together at Hollister Hills, and after Joe beat Myles by a second, Gary offered him a $6,000 salary and $8,000 in expenses to finish out the NORBA racing season riding for Gary Fisher.

Mountain biking was officially exploding, and Gary, Mert and Joe were at the center of it. Bikes were selling, money was pouring into the race scene and the sport was gaining mainstream attention. Joe left his motocross dreams behind and found success racing for Gary Fisher, finishing in the top 10 overall that year.

Even after so much success, however, Gary and the Lawwills parted ways when Fisher was sold to Trek in 1993. The company wanted to use its own suspension design so the Lawwills took everything they’d been working on and found another investor, creating the Trophy Lawwill bike. They added an air shock and increased the travel to four inches, yet the bike was still under-gunned for the evolving downhill scene. With a need to overhaul their design and an investor who wasn’t willing to provide them the means to do so, the Lawwills sought to find an established brand to develop their platform with.

YETI-LAWWILL DH-6

There was no question the Lawwill suspension design worked. It had won awards and graced podiums, yet for some reason it couldn’t find a reliable frame manufacturer to coexist with. Enter John Parker.

Durango, Colorado-based Yeti Cycles had been gaining momentum for more than a decade, and by the mid 1990s they were recognized as an industry leader when it came to mountain bikes and racing. In 1995, as Yeti was being acquired by Schwinn, Mert and John developed a downhill bike that used a Schwinn front triangle and Trophy rear suspension. Elke Brutsaert rode the prototype bike to victory at the Big Bear, California World Cup, with Joe coming in sixth on the Trophy Lawwill version undeniably validating the suspension design.

“We were confident in him and we were behind him,” John says. “All the bikes that had his name on them, he was driving the boat and there were no compromises—this was Mert’s bike and I was there to give him the opportunity to fully invest himself in this thing.”

Mert was brought on as the company’s suspension consultant, while Joe was named to the Yeti race team alongside up-and-comers Kirt Voreis and Colin Bailey. During his time with the company, Mert helped develop their downhill bike, which was offered with either four or six inches of travel and known as the Lawwill DH-4 and DH-6. With a rear disc brake, a front rim brake, a dual-crown fork and a pull-coil shock that was directly influenced by Mert’s knowledge of auto racing, the bike was state of the art when it officially released in 1997. Mert’s suspension design was also used on Yeti’s Straight Six, Straight Eight and Four Banger bikes during that time.

On the World Cup circuit, Kirt and Colin were initiated into the ways of research and development that Mert and Joe had been using for years. The popularity of downhill mountain bike racing was skyrocketing, and with it came a tidal wave of money—both in business and on the podium. The sport got serious quickly, which meant that progression needed to happen at an even faster rate. Just as in Mert’s flat-track days, new knowledge was confidential, and anything that could make a bike faster by even one one-hundredth of a second was deemed essential.

“We were developing everything at once, and that was the crazy part about it,” Voreis says. “It wasn’t like we were just working on one thing. We’re testing tires, we’re testing suspension, we’re testing brakes—and Mert knew about everything.”

“We were developing everything at once, and that was the crazy part about it. It wasn’t like we were just working on one thing. We’re testing tires, we’re testing suspension, we’re testing brakes—and Mert knew about everything.”—Kirt Voreis

Yeti would rent the Texas A&M wind tunnel every January 1, 2 and 3 (that’s when it was the cheapest), John remembers. Or when they were in Austria for a World Cup race, he and Mert would meet with Kenny Roberts and the Yamaha racing team at the A1 Grand Prix to see how they conducted their R&D.

“We left nothing unturned when it came to winning a race,” John says.

The glory years of Schwinn and Yeti were short lived, however. With poor management by corporate executives, the once humble company seemed to have forgotten its identity. So, in 1999, after two brief transfers of ownership, the company was bought by employees Chris Conroy and Steve Hoogendoorn who intended to take Yeti back to its roots, which meant developing an entirely new suspension platform—without Mert’s design.

MERT'S HANDS

When Mert stopped designing bicycles, he concentrated on ways to help people ride them. Chris Draayer, a fellow Harley Davidson factory motorcycle racer, suffered a brutal crash in 1967 in which he lost his left arm. Because he’d seen Mert fabricate things for his motorcycle, Chris asked him to build a prosthetic arm and hand. With help from Dave Garoutte, a CNC machinist, they developed a ball-and-socket joint that would work for any type of handlebar.

Just like bicycle pivot points, prosthetic joints must be in a specific location to deliver a precise result. With a little trial and error, Mert was able to find a design that is suitable for almost anyone who needs a prosthetic limb. This invention became his business Mert’s Hands, and to date there are more than 300 of them out in the world. That might seem like a small number, but it’s pretty significant if you’re one of the people using one, Mert points out.

“It really changes their life because it gets them back on wheels again,” he says.

Leave it to Mert, ever the innovator, to always find something that could either be better or that simply doesn’t exist yet. Thanks to his contributions to the mountain bike and motorcycle worlds, he was inducted into the Mountain Bike Hall of Fame in 1997, and into the Motorcycle Hall of Fame the year after. He still lives in Tiburon, and still loves to tinker. And he doesn’t hesitate to brag about his children and grandchildren.

From his days racing flat track to the time he spent in World Cup pits, few—if any—two-wheeled contraptions have passed by him without being improved upon. He holds seven suspension patents, and while they might no longer be in widespread use, they remain the foundation of the modern mountain bike.

“That’s one of the prouder accomplishments of my life, working with Mert back then,” John says. “The stuff that we did was nothing short of magical.”

![“Brett Rheeder’s front flip off the start drop at Crankworx in 2019 was sure impressive but also a lead up to a first-ever windshield wiper in competition,” said photographer Paris Gore. “Although Emil [Johansson] took the win, Brett was on a roll of a year and took the overall FMB World Championship win. I just remember at the time some of these tricks were still so new to competition—it was mind-blowing to witness.” Photo: Paris Gore | 2019](https://freehub.com/sites/freehub/files/styles/grid_teaser/public/articles/Decades_in_the_Making_Opener.jpg)