Destiny and Daydreams The Path to a Mountain Bike Paradise in Oregon

Words by Nick Gibson & Adam Craig

Do you believe in destiny? Part of me likes to think so, and I’d like to think destiny is also why you’re reading this article.

My connection to the great state of Oregon could have everything to do with destiny, too, stemming all the way back to my Midwestern childhood, when I grew up playing a computer game called The Oregon Trail.

This game was designed to teach schoolchildren about the realities of 19th-century pioneer life on the Oregon Trail. Each player assumed the role of a wagon leader guiding a party of settlers from Independence, Missouri, to Oregon’s Willamette Valley, using a covered wagon during the Gold Rush of 1848. The interactive game required players to complete simple math equations, make navigation decisions, hunt for food, shop for supplies, know when to rest, and, most importantly, to daydream about frontier life.

Fast forward to 2007, 20 years after my last game of Oregon Trail, and I’d found myself living in Oregon, helping guide mountain bikers on the trails covering our vast landscape. Oregon boasts a perfect blend of ecology, geology and topography, resulting in terrain that feels designed for the mountain bike. It’s the place you dream of riding.

The crown jewels of Oregon's riding are it’s trail surfaces. Seasonal accumulation of diverse organic material sustains the soil and produces remarkable riding conditions across the state. While skiers dream of blower powder, those of us on two wheels revel in the gleeful flow of brown powder and the duffy berms of Oregon’s expansive trail systems. But you need not be a soil scientist to get the most out of riding here: The simplicities of laughing and riding with friends, floating through the forest and experiencing the kindness of local communities frame our Oregon mountain biking experiences. If you choose Oregon as your next place to ride, you’ll likely find exceptional dirt, never-ending singletrack ribbons, glorious volcanic peaks, waterfalls, sweet jumps and old-growth trees deep in the backcountry.

Northwest Oregon alone features a staggering concentration of world-class riding destinations, from the bustling city of Portland to smaller towns such as Bend, Hood River, Oakridge and Pacific City. While all of these places have different landscapes, climates and community vibes, they are bound together by their exceptional mountain biking options. Many of northwest Oregon’s riding areas are in the foothills, but the joint influences of the Cascade Range and the Pacific Ocean are the primary factors contributing to the state’s diverse climate.

The Cascades extend from Mount Lassen in Northern California to the confluence of the Nicola and Thompson rivers in British Columbia, Canada, bisecting Oregon from north to south. A unique band of thousands of small, young volcanoes comprise the range, with a few strikingly large volcanoes dominating the landscape. West of the Cascades, temperate rainforests cover the land, providing a voluptuous evergreen canopy rich in Douglas fir and hemlock. The weather is typically wet in the winter, with perfect dirt in the spring and fall, and dry conditions during the summer. Here you’ll find 3,000-foot descents past carpets of deep-green moss and vibrant ferns, all in the shadow of towering trees—many of them, old-growth giants.

East of the Cascades, the eastern two-thirds of the state experiences dry summers and cold winters. Juniper and ponderosa pine rule this landscape, affording sweeping views through open canopies. The high-desert climate of this region offers a change from the west side, with considerably more sunshine and seemingly endless stretches of open terrain.

While riding conditions statewide typically peak in the summer and fall, mountain biking in Oregon is a year-round activity. During the winter months riding is relegated to lower elevations, where mud spikes, fenders, waterproof gear and a positive attitude are required. Dominant high pressure returns in late spring, with abundant summer sunshine to melt deep snowpack—just in time to ride all of the great high-country trails well into fall, when moisture returns and the cycle repeats.

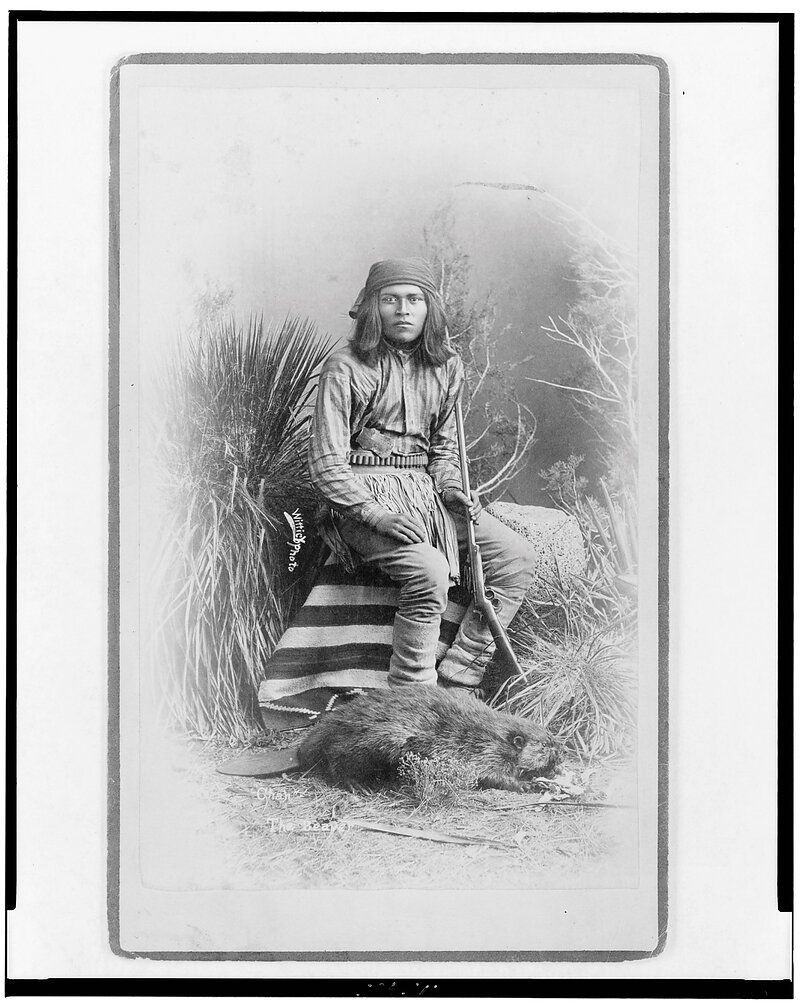

From the crest of the Cascade Range to the more populated valleys and flatlands, trails have long been part of this landscape. Native American tribes such as the Modoc, Molalla, Kalyapua and Warm Springs developed and shared trails for access to hunting, fishing and trade. These trails were the first transportation networks, essential to tribal life and survival. The existence of these subsistence communities revolved around following re-sources through seasonal changes, with various growing seasons and animals moving to and from the high country. The valley floor provided easier winter travel, while ridgetops became accessible for summertime vantage points. Navigational markers such as blazes, cairns and trail trees have been used for thousands of years to help guide travelers, and observant riders will occasionally catch a glimpse of these historical road signs.

TIMBER HARVEST DOMINATED THE LANDSCAPE, COMMUNITIES, POLITICS AND THE ECONOMY THROUGH MOST OF THE 20TH CENTURY. TOWNS QUICKLY GREW TO KEEP PACE WITH THE PROSPEROUS LOGGING INDUSTRY, AND THESE HARDWORKING COMMUNITIES FOSTERED A UNIQUE CONNECTION TO THE OUTDOORS.

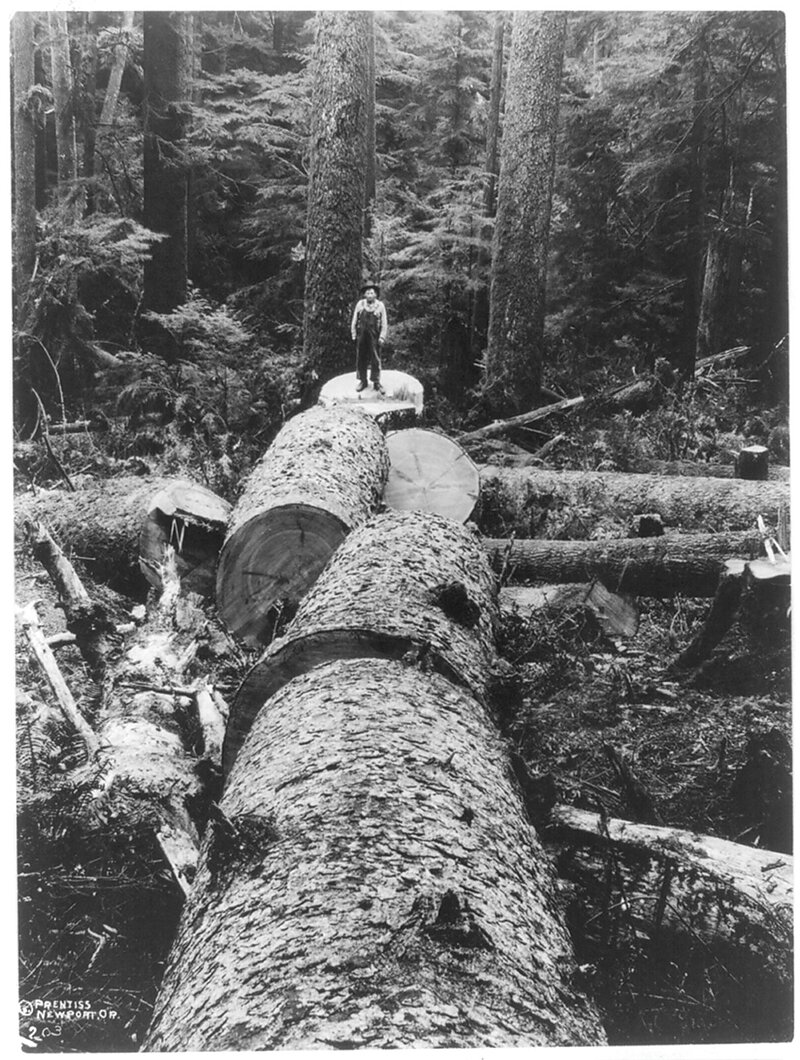

In terms of historic significance and economic impact, logging has long led the charge in infrastructure development of Oregon’s forests. The industry’s roots are shadowed only by the powerful overstory of modern timber wars and consequential land-use designations. The first water-powered sawmill was built at Fort Vancouver in 1827 to augment the single-bit axes that were cutting down massive trees. The state’s first timber exports were to China in the 1830s, creating an export economy around this renewable cash crop. Access to the forest was by waterways, primitive roads and backcountry trails. Pack teams and waterways transported timber during this era, restricting activities to the valleys and foothills.

With gains made during the Industrial Revolution, 20th-century logging took on a new look. Power saws and heavy machinery pushed the timber industry deeper into the mountains, seeking to keep tight-grain, old-growth logs feeding the ever-expanding lumber mill network. The Forest Reserve Act of 1891 authorized the Department of the Interior to begin transferring land from public domain to forest reserves, triggering the acquisition of lands managed by the agency that would come to be known as the United States Forest Service (USFS). With 60 percent of Oregon’s forested land under federal management today, a tremendous amount of public land access is supported by a mountain road system that only logging money could have built.

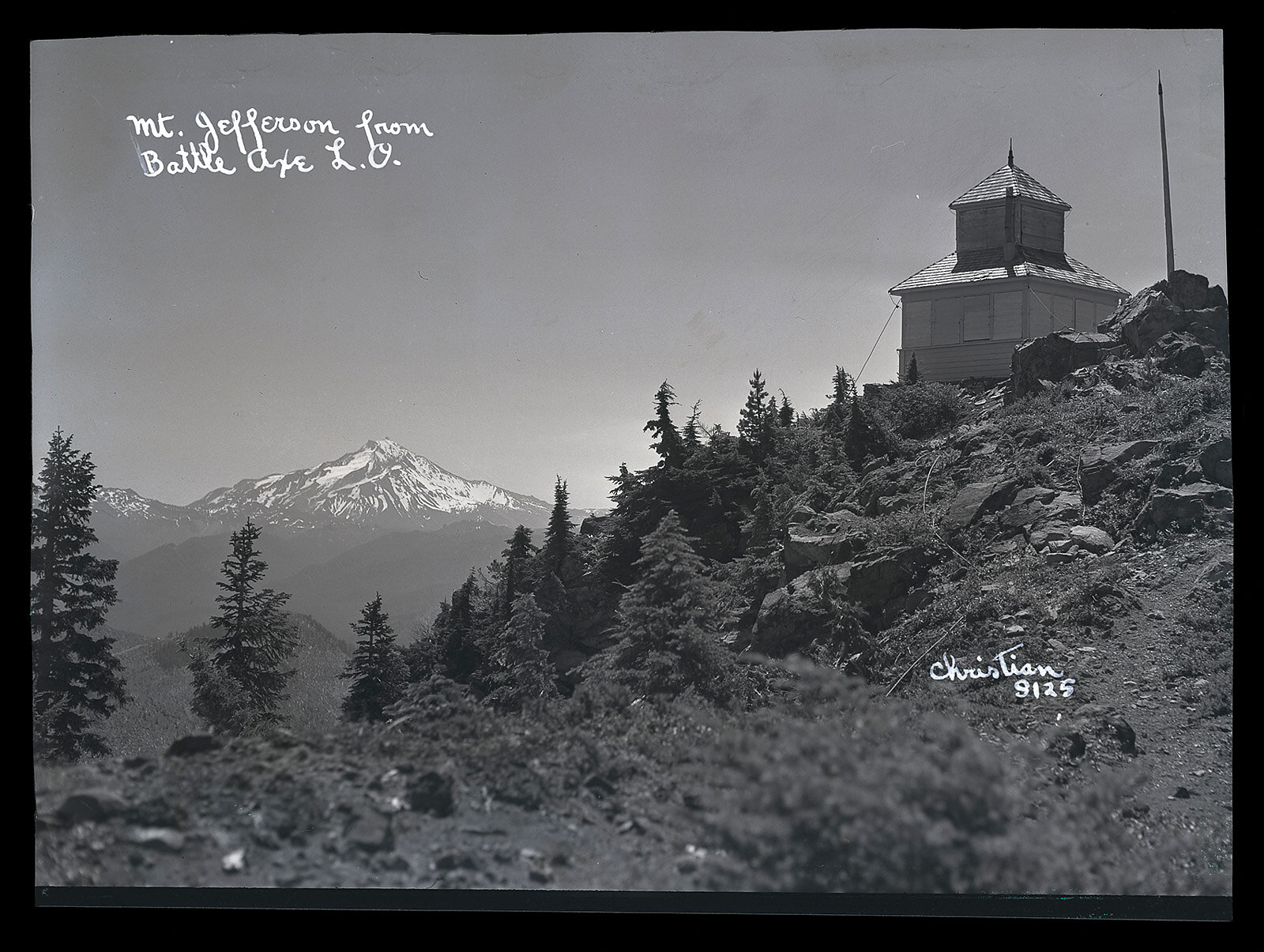

Increasing demands on land use called for heightened pressure on its management. In 1905, the USFS’s Chief Forester, Gifford Pinchot, instituted a “total exclusion” policy of forest fire management. By 1916, there were 81 fire lookouts on mountaintops around the western logging forests. With President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1933 creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) as part of the New Deal, 300,000 people suddenly became available each year to work on the federal lands of the west for $30 a month. During the CCC’s nine-year term, the number of fire lookouts increased 100-fold.

Access to and communication for this boundless observation system was by trail, with those dual priorities yielding two distinct trail types. Pack animals used for supplies required reasonable grades, necessitating a deep bench cut and infinite switchbacks to be constructed, which the CCC did in a timeless, sustainable and artful manner. Herein, the practical singletrack aesthetic that mountain bikers now find beautiful was born. Time-sensitive communication was often delivered by runners, who used a primitive system of ridgeline trails that eventually dipped straight down the fall line to the valleys. Though few of these remain today, those that do are especially cherished by mountain bikers on modern enduro bikes.

Timber harvest dominated the landscape, communities, politics and the economy through most of the 20th century. Towns quickly grew to keep pace with the prosperous logging industry, and these hardworking communities fostered a unique connection to the outdoors. Timber sales funded recreational development during the boom years, including multi-use trails richly enjoyed by local communities. The Willamette National Forest, centrally located in the Oregon Cascades and producing the most timber of all the national forests, benefitted tremendously. The design and construction techniques of the CCC provided trails remarkably well-suited to mountain biking, and while the riders of today are mostly sheltered from the high-stakes lifestyles of the loggers and native travelers of yore, many of the tight switchbacks, turns and natural features remain for us to enjoy.

With the bitter fight surrounding the Northwest Forest Plan and its subsequent passage in 1994, the timber industry was forced to adjust. This plan did not specifically curtail logging, but it confirmed the application of the National Environmental Policy Act to any planned action on federal lands, regardless of whether they were recreational, commercial or otherwise. Environmental impact studies have led to limits on forest use and greatly increased the time needed to assess the potential impact of each proposed project. As a result, logging has moved steadily onto large, private land holdings, while the use of federal land for recreation has increased

MEMBERS OF EQUESTRIAN GROUPS HAVE NOTICED THE INCREASING MOUNTAIN BIKE PRESENCE AND HAVE CASUALLY DROPPED INTO EVENTS TO SEE WHAT IS HAPPENING.

These changes have since had a dramatic impact upon the many small towns of timber country, with the loss of logging jobs forcing people to migrate to bigger population centers. Though several of these towns grew rapidly, the sheer expanse of wild public land in the state meant many Oregonians still had ready access to trails out their back doors. With the sport of mountain biking undergoing its first major boom in the 1990s, growing numbers of Oregon riders began to uncover the vast historic trail resources logging had left in the Cascades and its foothills.

Looking for adventure, good times and a connection with nature, mountain bikers in population centers such as Portland, Bend, Ashland and Hood River had discovered a paradise of singletrack. But they quickly realized that precious few of these trails were maintained for mountain bike use, as the decline in timber income for the Forest Service meant a corresponding decline in its recreation budgets. As a result, groups began forming in these communities to address these issues. Nonprofit organizations such as the Greater Oakridge Area Trail Stewards, the Central Oregon Trail Alliance and the Portland Urban Mountain Pedalers (PUMP) were established to manage existing resources and support mountain biking’s growth. The work ethic and diplomacy of some of these groups laid a foundation for healthy relationships with federal, state and local land managers, in most cases allowing for well-managed, collaborative growth.

With the popularity of mountain biking exploding all over Oregon—and local riders keen to have trails and connectors closer to home—many rogue trails were built in the 1990s. A majority of these were well-constructed by passionate, discerning volunteers who created them with a view toward sustainability. Due to these trails’ popularity and increasing traffic, there was a pressing need for them to be sanctioned, and early trail advocacy organizations were hugely instrumental in bridging the gap between trailbuilders and federal, state and local land managers in order to gain their adoption as legal networks. Today, these networks are models of sustainable recreation development, and they’re helping to bring about progress in their communities while also contributing to local economies.

Considering the vastness of Oregon’s landscape, even with the currently high level of volunteer effort, it has proved impractical for local trail groups to care for the huge swathes of backcountry singletrack that lie between the population centers. Though equestrian groups such as the Backcountry Horsemen of America and the Eugene-based Scorpions have historically cared for backcountry trails, in recent years their memberships have remained flat, leaving them with limited resources and forcing them to focus mostly on designated wilderness areas.

As a result, mountain bike groups with a statewide backcountry focus have emerged, adding much-needed maintenance capacity in many remote corners of Oregon’s forests. Organizations such as Trans-Cascadia have focused on advocacy in support of events, like the annual Trans-Cascadia Enduro Race, while the Oregon Timber Trail Alliance has rallied awareness and volunteerism for its long-distance bikepacking route, the Oregon Timber Trail (which traverses the Cascades from California to Washington). By sharing the experience of these events and developments, they have attracted enthusiastic volunteers from all over Oregon, resulting in just enough hands to get these remote jobs done.

Members of equestrian groups have noticed the increasing mountain bike presence and have casually dropped into events to see what is happening. These elder statesmen of trail stewardship have welcomed our involvement and are helping our new generation to learn the subtleties of tasks like bridge building, brushing and drainage techniques. Meanwhile, the Forest Service is assisting in connecting the dots between mountain bike and equestrian groups, with skeleton crews of savvy Forest Service staff maintaining hundreds of miles of singletrack every season. Communicating with and working alongside nonprofits has greatly enhanced the Forest Service’s ability to address the ever-present backlog of trail maintenance. The respect and trust that has been fostered between these groups has resulted in better-maintained backcountry trails for the basic purpose of public enjoyment.

IN A STATE AS BIG AND COMPLEX

AS OREGON, THERE WILL ALWAYS BE CHALLENGES TO FACE, BUREAUCRACIES TO ENGAGE AND OLD-GROWTH LOGS TO CLEAR, BUT THE GROWING MOUNTAIN BIKE COMMUNITY HAS SO MUCH PASSION AND KNOWLEDGE IT IS PREPARED TO MEET THESE CHALLENGES.

As mountain biking continues to grow in the 21st century, a fresh wave of local trail organizations is forming. In 2010, Portland-based PUMP became the Northwest Trail Alliance (NWTA), and it has been growing rapidly as options for riding in the greater Portland area are beginning to take shape. The NWTA’s membership-driven model of developing trails on private timber-company land has led to the development of an impressive sustainable trail network at Rocky Point, just west of the city. For their part, the Hood River Area Trail Stewards manage a complex relationship with the county forest to maintain and develop their network at Post Canyon. Near the small coastal town of Pacific City, the Tillamook Off-Road Trail Alliance has been formed by a core group of locals with plans to develop an extensive network on neighboring public lands. After three years of planning and permitting, their triumphant shovels will sink into that dreamy coastal soil this spring, with an intermediate trail from Buzzard Butte to the edge of the ocean slated for completion in the fall of 2021.

With a current total of 21 mountain bike trail groups in Oregon, the final piece of the advocacy puzzle is the development of a statewide organization. Just to the north, Washington’s Evergreen Mountain Bike Alliance has paid staff all over the state, working with its chapter programs on all manner of mountain bike advocacy initiatives. Drawing from this model, a small group of volunteers in Oregon recently formed a steering committee to develop what is tentatively being called the Oregon Mountain Bike Coalition. Support has been widespread, and the idea of connecting our statewide advocacy network and directing a united voice to the capital has already proven beneficial.

In a state as big and complex as Oregon, there will always be challenges to face, bureaucracies to engage and old-growth logs to clear, but the growing mountain bike community has so much passion and knowledge it is prepared to meet these challenges. And with the fast-exploding generation of young riders and aspiring trail stewards coming of age, the future of mountain biking in Oregon looks bright. It all comes back to kids learning to ride bikes and dreaming of their lives at the end of the Oregon Trail. That, and destiny.

Enjoy what you just read? Consider joining or donating to the advocacy groups and trail builders that make these areas possible.

![“Brett Rheeder’s front flip off the start drop at Crankworx in 2019 was sure impressive but also a lead up to a first-ever windshield wiper in competition,” said photographer Paris Gore. “Although Emil [Johansson] took the win, Brett was on a roll of a year and took the overall FMB World Championship win. I just remember at the time some of these tricks were still so new to competition—it was mind-blowing to witness.” Photo: Paris Gore | 2019](https://freehub.com/sites/freehub/files/styles/grid_teaser/public/articles/Decades_in_the_Making_Opener.jpg)