Destined For Greatness Angelo Washington's Journey From The Baseball Diamond to Downhill Brilliance

Words by Jess Daddio

Dig back far enough through Angelo Washington’s YouTube channel and you’ll find “The Experience.” Posted at the end of 2014 Washington’s first year of riding—the video captures one of his earliest forays on his new bike, a clapped-out, 26-inch, gunmetal gray Dawes Roundhouse he scored off Craigslist for $300. The shaky, pixelated GoPro footage shows Washington’s point of view, which looks down on his long stem and narrow handlebars as he navigates the trails at Powhite Park in Richmond, Virginia.

When Washington’s tires leave the pavement and hit dirt, red text sprawls across the top of the screen. It reads, “No turning back now!” There is no introduction and no narration; just five minutes of newbie mountain bike action. The climax of the video comes at the three-and-a-half-minute mark, when Washington stuffs his front wheel into a root and dives headfirst over the handlebars. The viewer is then treated to a slow-motion replay of his crash set to an orchestral soundtrack, which ends with Washington splayed out in the leaves.

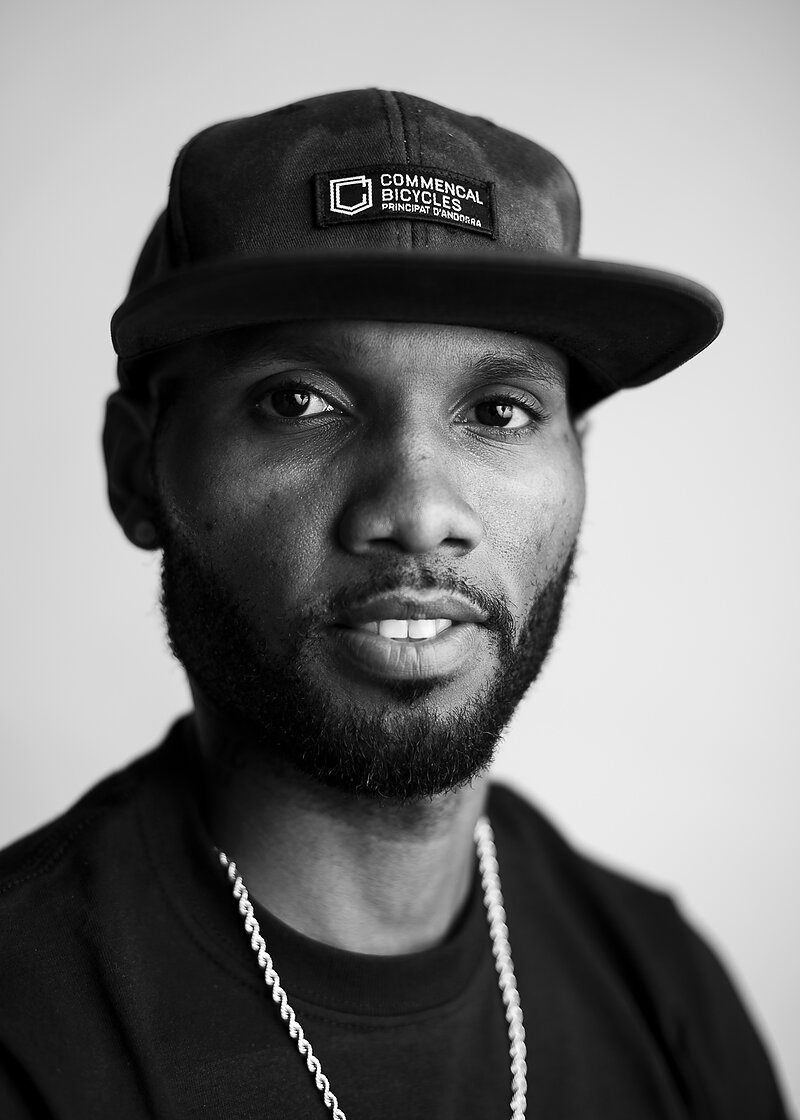

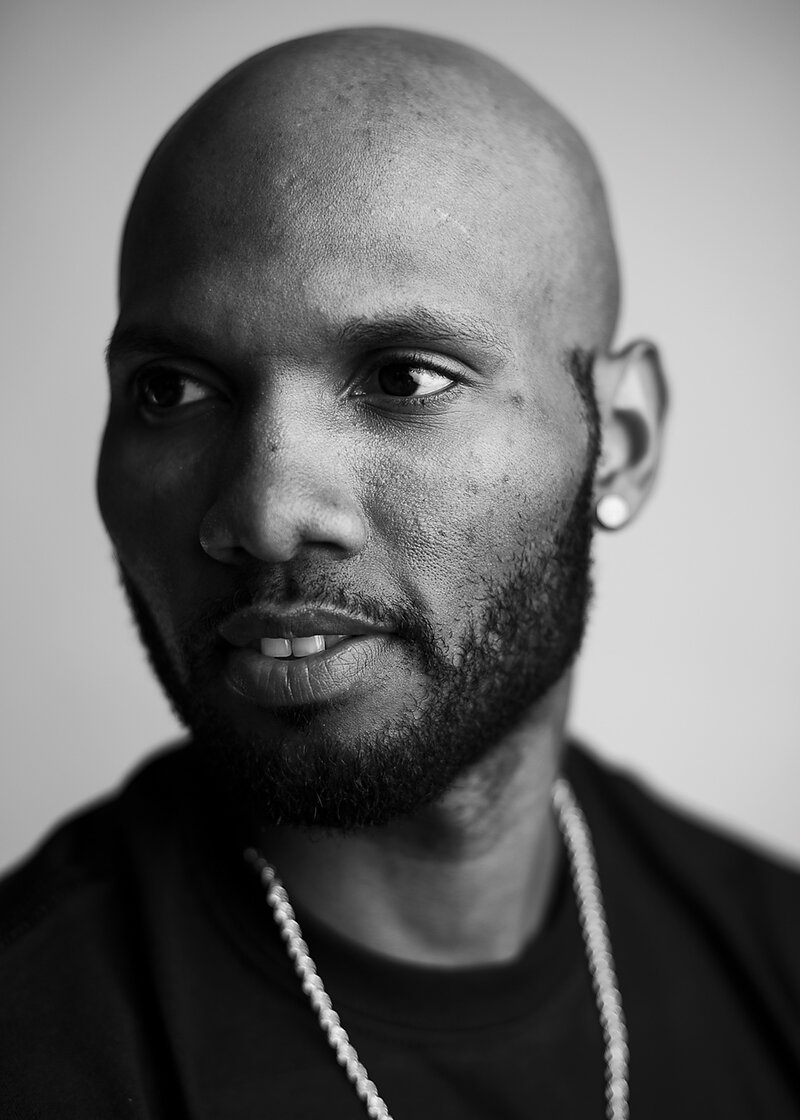

What’s remarkable about this video isn’t the clip itself, although it’s endearing in a home-movie kind of way. Rather, it’s a fascinating glimpse of Washington’s first deep dive into mountain biking, which makes his extraordinary skills progression all the more impressive. Today, if you race downhill in the southeastern United States, you probably know Angelo. After his first racing season in 2016, Washington, now 36, quickly blazed through the downhill amateur ranks. In 2020, he moved up to racing Category 1 and now receives support from Commencal, 100 Percent and Etnies.

Much like his riding, his YouTube game has stepped up, too: a better GoPro, a clever handle (Angeloam_Duff), custom thumbnails, interviews with pros, an ever-growing fan base. Washington’s vlogs are still raw in feel, what he calls “Angie’s Style.”

“It’s about me telling my story not as a professional rider but as your everyday dad rider,” Washington says. “I want people to see that I’m out here trying, and I do fail. It’s not just me showing all of my successes.”

Washington’s road to success, both on the bike and in life, has been winding, full of unexpected detours and sudden pit stops. But to fully appreciate his journey, there are two things you should know: Before he loved bikes, he loved baseball. And before he loved baseball, he loved wolves.

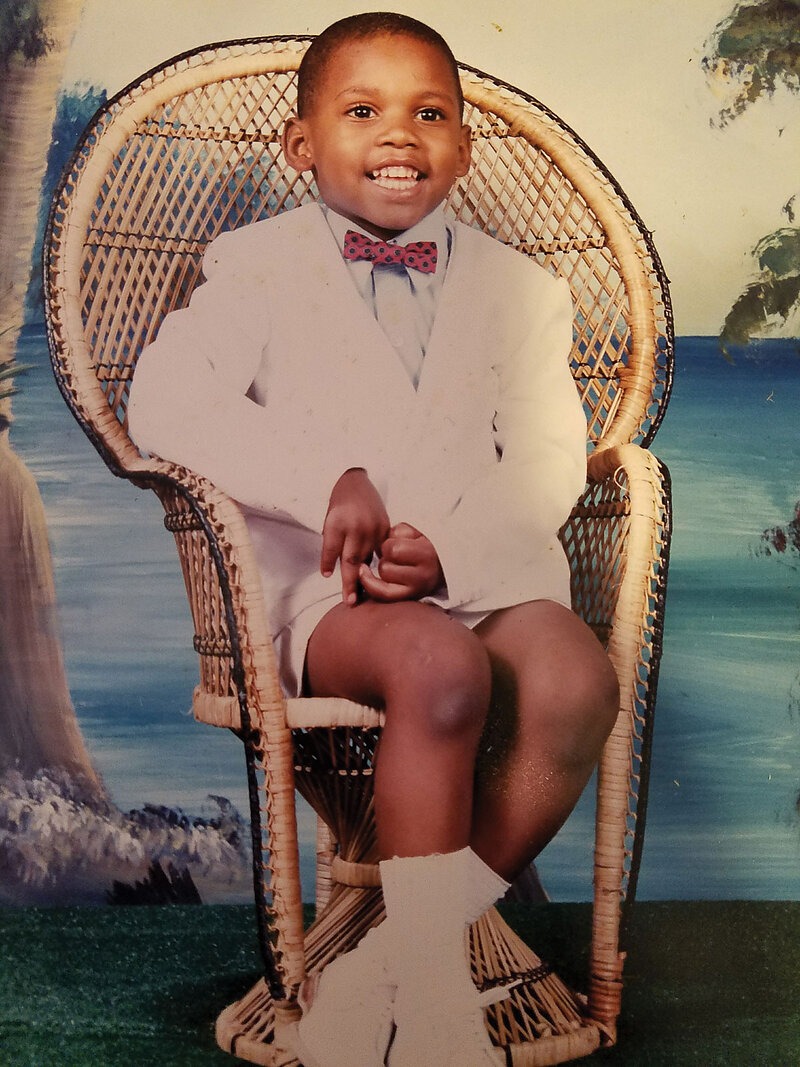

Angelo was born DeAngelo Keon Washington on May 30, 1986. When he was two years old, his family moved to Creighton Court, the second largest housing project in Richmond’s East End. Life in the majority Black, low-income neighborhood of Creighton Court had its challenges, particularly during the ‘80s and ‘90s, when Washington was growing up. Generational poverty perpetuated by an intrinsic system of redlining left little upward mobility for public housing residents. Drug-related crime and gun violence haunted the streets. Neighborhood rivalries kept families on edge.

But Washington didn’t see things that way, at least not at first. He was a dreamer. And for as long as he can remember, he has dreamed of wolves. Yet Creighton Court was a far cry from a suitable wolf habitat. It was a dead-end neighborhood with scant trees and rows of identical brick apartment buildings. Regardless, Washington answered the call of the wolf.

“I remember my mom being on the front porch with her friends and if it was a full moon that night, I’d just go busting through the front door running around in circles howling,” he says. “I like the way [wolves] move as a pack.”

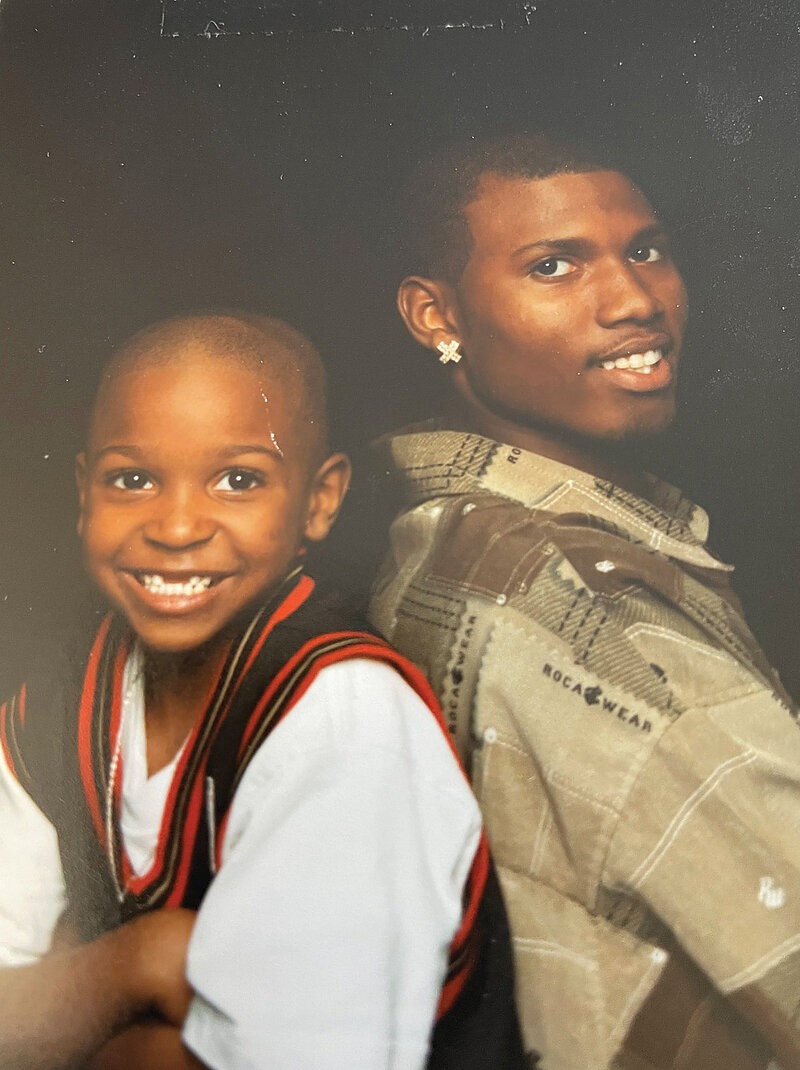

By the time he was eight years old, Washington was beginning to find a pack of his own. Larry “L.C.” Baker was part of that pack. Like Washington, Baker was a dreamer who lived in Creighton Court. They played recreational ball together, perfected animal noises together (“D got a mean horse, we both got a solid cow,” Baker says). They even got matching “D4G” tattoos, a reminder that they were “destined for greatness.” When older kids in the neighborhood paid younger kids to start fights for entertainment, Baker and Washington played games instead.

“We were fight-averse,” Baker says. “Where we’re from, crime and opportunity are one and the same. Living in that environment, there’s so much that was pulling on some of the guys around us, even at eight [years old].”

Sometimes though, the trouble found them. Once, when Washington was walking home from middle school, a group of guys from Mosby Court—another public housing project in Richmond’s East End—snuck up from behind and beat him up, unprompted and for no other reason than that he was from Creighton Court. Back then, Mosby and Creighton were openly hostile to each other. If you were a kid in one neighborhood, it was expected of you to not have friends in the other.

It would have been easy to retaliate. Guys around Washington and Baker did it all the time. In a way, that’s how you earned respect. But Washington and Baker weren’t like the other guys. They had sports, and they had each other.

“That sage wisdom within the context of the projects always protected us,” Baker says. “Sports are what earned the respect of people for us.”

First, it was basketball. Washington was a sharpshooter but he hated to dribble, Baker says. Next came football. Where Baker, a wide receiver and running back, was fast on foot, Washington’s strength was his precision. His aptitude for accuracy made him a natural quarterback.

What didn’t come naturally for Washington was school. Reading and comprehension proved especially difficult. Adding to those academic challenges was a missing link at home. Though he came from a two-parent household, it was his stepfather who raised him. Washington resisted his stepfather’s authority. He sought a father figure elsewhere, mostly from his friend Eric Ross, or “Eball,” an older kid from Creighton who also played football. Eball’s mother battled addiction and his father was absent. Washington admired Eball for how he stepped up as a teenager to provide for his siblings.

But the man who guided young Washington the most was Coach Lamont Davis. Davis was Washington’s freshman English teacher and the head baseball coach at Armstrong High School. It was Davis who introduced Washington to baseball, mentored him in school and held him accountable in life. Washington felt seen by Davis, who called him “Young Fresh to Death.” Even today, he still considers Davis a father figure.

“He took me under his wing and taught me how a man is supposed to move in the world,” Washington says. “He was the ultimate role model. He was loved all the way around and was big on respect to others but also respect to self.”

Washington took those lessons to the baseball diamond. There, he flourished. His strong arm and detail-oriented nature had found the perfect outlet. He played shortstop and second base and was lethal at both.

Washington’s longtime teammate, Doron Battle, remembers meeting him for the first time. It was the summer of Battle’s 13th birthday and the two were traveling to Baltimore for a game, a first-time experience for both playing on a team made up entirely of kids who lived in public housing. At 5 feet 8 inches and 130 pounds, Washington was a little slight but neatly dressed, with a crisp sense of style and a cheeky grin.

“In the hood if you play baseball, you’re an anomaly as is,” Battle says. “I’m from Mosby and we didn’t fool with those guys. But I remember lookin’ at him like, this dude’s alright. It’s like the universe put us together.”

Battle and Washington clicked. Together they made a formidable middle infield, swapping shortstop and second base positions. During games they anticipated each other’s moves, read each other’s minds, a seamlessness that Battle later likened to “poetry in motion.”

As they grew older, Washington’s bond with his pack began to evolve. His family moved out of Creighton Court during his junior year and, though he played baseball at his new school, it wasn’t the same without Battle. Baker went to college two hours away. After graduation, Washington tried to play baseball for Virginia State University but only received enough financial aid to study for two semesters. In 2007, the same year he dropped out of college, his first daughter, Ariel, was born. Washington set aside his academic ambitions and took a job at Home Depot.

During his lunch breaks, he passed the time by sketching. Be it logos or buildings, it was clear Washington had an eye for design. A fellow employee took note of his sketches and encouraged him to apply to ITT Technical Institute. After three tries, he passed the entrance exam.

“IN THE HOOD IF YOU PLAY BASEBALL, YOU’RE AN ANOMALY AS IS. I’M FROM MOSBY AND WE DIDN’T FOOL WITH THOSE GUYS. BUT I REMEMBER LOOKIN’ AT HIM LIKE, THIS DUDE’S ALRIGHT. IT’S LIKE THE UNIVERSE PUT US TOGETHER.” - DORON BATTLE

If you ask Baker and Battle, they’ll tell you what followed was the beginning of an evolution, a time when Washington’s path made a few sharp turns. First, Washington bought a white Ford F-150. Then he started listening to bands such as Trillium, Killswitch Engage and the Misfits. He took Baker and Battle to a Slipknot concert. He talked about getting a pet wolf and a lift kit for his truck. Washington was living full throttle, in his own way.

“That was an interesting DeAngelo,” Battle says.

Five days a week he worked from 6 a.m. to 4 p.m., three nights a week he went to school from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m., and during the rest of his waking hours he played ball or doted on Ariel. By then, he and Battle were back in the infield together, playing for a double-A team called the Richmond Braves. Life was ripping right along. In the years that followed he got his associate degree in computer drafting and design, secured a job at an architectural and civil-engineering firm, welcomed his second daughter, Kaili, to the world and started coaching varsity baseball with Battle. Though he relished fatherhood and his newfound career, baseball was more than a hobby: It was his identity.

On the field, Washington was studious and systematic, exacting in his technique. Even his uniform was tight, never baggy. On game day, jerseys and tape and cleats were color coordinated. When he coached, he brought that level of detail, too, but never at the expense of having fun. If the kids hit a mental wall during practice, Washington took them to the outfield to dance. Once, when their varsity team lost 29-0, Battle and Washington threw the kids a party on the bus. No matter how dark the circumstances, Washington always seemed to find the light. “A core piece of D is his laugh,” Baker says.

But in 2014, Washington’s love for baseball was thrown a curveball. During warmup one day, an eight-ounce weight flew off the end of a teammate’s bat and crushed him in the face. The impact was so great it knocked him unconscious, fractured his face in five places, busted his lip open and broke two of his teeth. Never one for indolence, Washington was back on the field just two months later. But during a tight playoff game, in the bottom of the ninth inning with the score locked at 0-0, Washington dropped a ball Battle threw to him on a double-play attempt. The error cost them the game, along with their chance to play in the state championship.

“He was so uncomfortable, and you could tell,” Battle says, remembering the incident. “DeAngelo was super precise about literally everything, down to the cleats. When he bobbled the two-ball, that’s when I knew it was way bigger than a physical accident.”

METHODICAL IN LINE CHOICE, INTENTIONAL IN FORM AND FRESH IN KITS, WASHINGTON APPROACHES BIKES JUST LIKE HE APPROACHED BASEBALL. HE WANTS TO PUSH HIMSELF, WANTS TO RIDE THAT FINE LINE BETWEEN CHAOS AND CONTROL.

After the accident and the disappointing end to that season, something shifted in Washington. Physically, he wasn’t the same. Eventually he had reconstructive surgery on his face. He often complained of headaches. Sometimes his vision was blurred. Mentally and spiritually, his unfettered love for the sport had changed too. He felt lost. At 27 years old, he was left grappling with an age-old question: What next?

Were it not for his colleague, Jeff Haas, Washington might still be looking for an answer. Not long after his accident, Haas, an avid cyclist, took him on a mountain bike ride after work. Washington remembers crashing a lot, but there was something about riding that soothed his soul. On a bike there was no team counting on him, no expectations other than his own. If he made a mistake, it hurt only him.

So, he bought the Dawes Roundhouse. Powhite Park was the closest trail system to his office. Every afternoon he could, he’d sneak in a ride before heading home. In a Misfits jersey, sneakers, soccer shin guards and toe clips (which he soon learned were not the same as clipless pedals), he learned to ride by trial and error. In early 2015, he started joining group rides held by a local nonprofit called Women’s Multisports of Richmond.

“My claim to fame is I taught Angelo how to ride,” Haas says, “Because I’d say I could keep up with [him] for a month or two of rides. He picked up on it real quickly.”

Though he continued to play baseball for one more season, even Washington knew he was starting to favor time on the trails over days on the diamond. Being in the forest under his own power was liberating. It was the closest thing to moving like a wolf. He had been in the Boy Scouts when he was young, but they’d spent more time selling popcorn than playing in the woods. In the spring of 2015, he upgraded his 26-inch Roundhouse to a 27.5-inch Diamondback Bicycles Atroz. Its maiden voyage was a mountain bike time trial at the Dominion Energy Riverrock festival, which was effectively Washington’s first race.

Cross-country racing was fun. Washington savored the intensity of going all-out on the course. But Richmond’s cross-country riders were serious to the brink of pretentiousness. So, later that spring, when Washington went to Snowshoe Bike Park in West Virginia and discovered the thrill of going downhill—and the group of folks that liked to send it, too—he finally felt as though he’d found his community.

“That first lap down Dreamweaver blew my mind,” he says of the machine-groomed trail. “Ever since then I’ve been making it my business to go to Snowshoe for opening weekend, closing weekend and every holiday in between.”

The following year, Washington committed to a full season of racing. Competition heightened the stakes. The feedback was instantaneous. If he didn’t put in the work, it would show in his results. And initially, results were what he wanted. In 2016, he podiumed in Category 3 at most of the races he entered. In 2017 and 2018, he stepped up to Category 2. He won his age bracket at the USA Cycling Downhill National Championships at Snowshoe in 2017 and came in third the following year. Between his early results and his dogged determination, Washington had no trouble establishing a partnership with Commencal.

“HE’S VERY CALCULATED. EVEN WHEN HE’S GOING DOWN IN A CRASH, IT LOOKS LIKE HE PLANNED IT.” - RONNIE VANCE

"It’s crazy to see how far he’s come,” says Washington’s friend and pro rider Ronnie Vance. “He’s very calculated. Even when he’s going down in a crash, it looks like he planned it. But sometimes you gotta risk it for the biscuit. He needs to loosen up and ride a race run like a practice run. His race results have never shown who he is as a rider.”

Methodical in line choice, intentional in form and fresh in kits, Washington approaches bikes just like he approached baseball. He knows his meticulous nature holds him back on race day. He wants to push himself, wants to ride that fine line between chaos and control. That edge is where he feels the most alive. But these days, what drives Washington more is not what he takes from the sport, but what he gives back to it.

Mountain biking gave Washington so much at a time when he desperately needed it. The sport gave him a challenge, a purpose. In riding he found clarity. Traveling to races with his daughters and partner in tow exposed not only Washington to new places and people, but also his family. While Washington raced, his family played at the resort. This opportunity has enabled Kaili to ride a horse and learn archery. The first time Ariel came to Snowshoe—now one of her favorite places—Washington can remember how she looked out at the vast expanse of deep-blue rolling ridgelines and asked if the mountains were water.

“We really take for granted little stuff like that,” Washington says. “It’s been my duty now—wherever I go they’re gonna take this in, just like I’m taking this in.”

His racing has influenced more than just his family. At the 2021 UCI Mountain Bike World Cup at Snowshoe, Washington fully realized the scope of his influence. For one glorious weekend in September, his West Virginia home mountain was swarming with some of the world’s top downhill racers. The likes of LoÏc Bruni, Greg Minnaar, Marine Cabirou and Tahnée Seagrave were there. And yet, as he walked through the crowds, it was not their names he heard. It was his.

“I’m not even a local pro, just a local Cat 1 amateur racer,” he says. “And I had kids coming up to me goin’, ‘Angelo, can we get your autograph?’ At first, I’m like, ‘You jokin’?’”

Washington treasures encounters with fans. He makes each and every one feel heard, feel seen, just like Coach Davis did for him years ago. Making strangers feel like friends is his secret power. He connects the most with his younger fans and strives to be a role model, one who’s eager to share the bigkid joy he’s discovered through riding bikes.

After decades of pursuing sport for himself, Washington now wants to bring sport—specifically mountain biking—to his community. When an event needs a group-ride leader, Washington is the first to step up. When he takes his girls to practice bike skills, he volunteers to help other kids learn, too. Washington will do anything he can to expose as many kids to mountain biking as possible, and not just through riding either.

This year, he’s even working with a Richmond public-school art class to create a new design for his helmet. He knows there will be obstacles (getting bikes to schools, providing transportation to trails, the financial burden of maintaining the bikes), but Washington has never backed down from a challenge: He has a will, and he will find a way.

“Even for his friends back home who don’t quite get riding, it’s amazing to see him balance these two worlds and still be himself in this sport,” says Washington’s partner, Verna. “It teaches Black and Brown kids that they can be a part of this sport, and it’s just as cool as baseball, basketball, football. He is filling voids in the biking community but also bringing his community with him. It’s just beautiful.”

Early in 2021, Washington received his level one mountain bike instruction certification. His skills instruction company is called Keep It Sketch, a reminder, he says, of the importance of stepping outside your comfort zone. It’s a lesson he wants his three daughters to know, that success is growth, not results.

“The hand he was dealt was crap,” Battle says. “And yet, he’s outliving a lot of people that had far more potential, in theory, than he did. I’ve never seen him more comfortable with DeAngelo the human than the present day.”

Washington never got a wolf for a pet. Instead, he settled for a German Shepherd he named Maxo, after the rapper Maxo Kream. But the way of the wolves, particularly the story of Wolf 21, still resonates with Washington. Wolf 21 was a black wolf. Raised by the wolf equivalent of a stepfather, 21 never lost a fight but always spared the lives of rival alpha males, an unusual generosity. After years of wandering on his own, 21 became the alpha male of the Druid pack, one of the largest and most successful wolf packs in the greater Yellowstone region’s history. Washington knows this because he’s listened to the audiobook version of “The Reign of Wolf 21: The Saga of Yellowstone’s Legendary Druid Pack” dozens of times. It is almost always queued up on his phone.

“Before he started his own pack he had to go through his own trials and tribulations. He got beat up a few times but then he thrived,” Washington says. “When I listen to the story of number 21, I think, ‘What if I could do this?’ I am him. That’s how I look at it. It gives me peace.”