Common Birthright Spreading the Wealth of Colorado’s Rich Inheritance

Words by Devon O'Neil

Everything you’ve heard about Colorado is true: the Saturday morning traffic congestion, the singletrack that looks like a strand of spaghetti, the enormity of landscape, the red rock walls, the kaleidoscopic flower fields, the suffering, the baby-butt smoothness, the access from your back door, the pink sunsets over purple peaks, the berms, the legends.

That’s the thing about stereotypes—they don’t just come from nowhere. They get beaten into cultural lore like tenderized meat, until the reputation is just soft enough, just firm enough, just fair enough to echo across state and country lines, over oceans and continents and through language barriers; to sweep up a global legion of adventurous devotees who hear what they hear and wonder for years what is fact versus fiction—who want to believe some but not all of it, before ultimately realizing they must experience it and decide for themselves.

Yep, Colorado is crowded. And dusty. And hot. And freezing at night in September up high, as the aspen leaves quake and glisten under the shiny moon. And magical in spring, when the trees are budding and the creeks are gurgling and the birds chirping like they haven’t in months. Colorado can be a tourist’s dream and a local’s nightmare at once. But, if one is being honest, so can a lot of places.

Maybe you know this, but mountain biking was born in Colorado. Well, kind of.

Still, you could argue that nowhere in American mountain biking is as polarizing as the Centennial State—a punchline to riders elsewhere in the West, a dream destination to those in the East, with more world-class fat-tire hubs inside its borders than anyplace not named British Columbia. It’s where you go to ride the red dirt of Fruita and the Kokopelli Trail, the never-ending ridgetops of the San Juans, the classics of Crested Butte, the spider web encircling Breckenridge, the gems that make the Front Range a city dweller’s fantasy, the sparkling aspen groves of Aspen. Colorado has seduced world champions and underground heroes for decades—and continues to this very day. Its namesake trail is a test piece. There is much to derive metaphorically from the fact that the Continental Divide splits it in two.

But, really, while all of that may belong in a bio, none of it defines the essence. That comes only in the moment, when you’re gasping for air at 12,000 feet above sea level, blitzing past yet another shimmering alpine lake, flowers as tall as your hip smacking your handlebar as you corner, their stamen exploding in your face so emphatically that you start to sneeze. Then your eyes begin to water, and the suffering you endured to reach this payoff sets in, blurring the spectacular scenery on all sides, immersing you in nature at its wildest.

Maybe you know this, but mountain biking was born in Colorado. Well, kind of. It is probably a testament to the sport’s inevitability—the absolute super coolness and ultimate necessity to our species of ripping down steep, rugged earth on two wheels—that not one but two places lay claim to its origin, accurately so in both cases. Don Cook remembers the moment they converged.

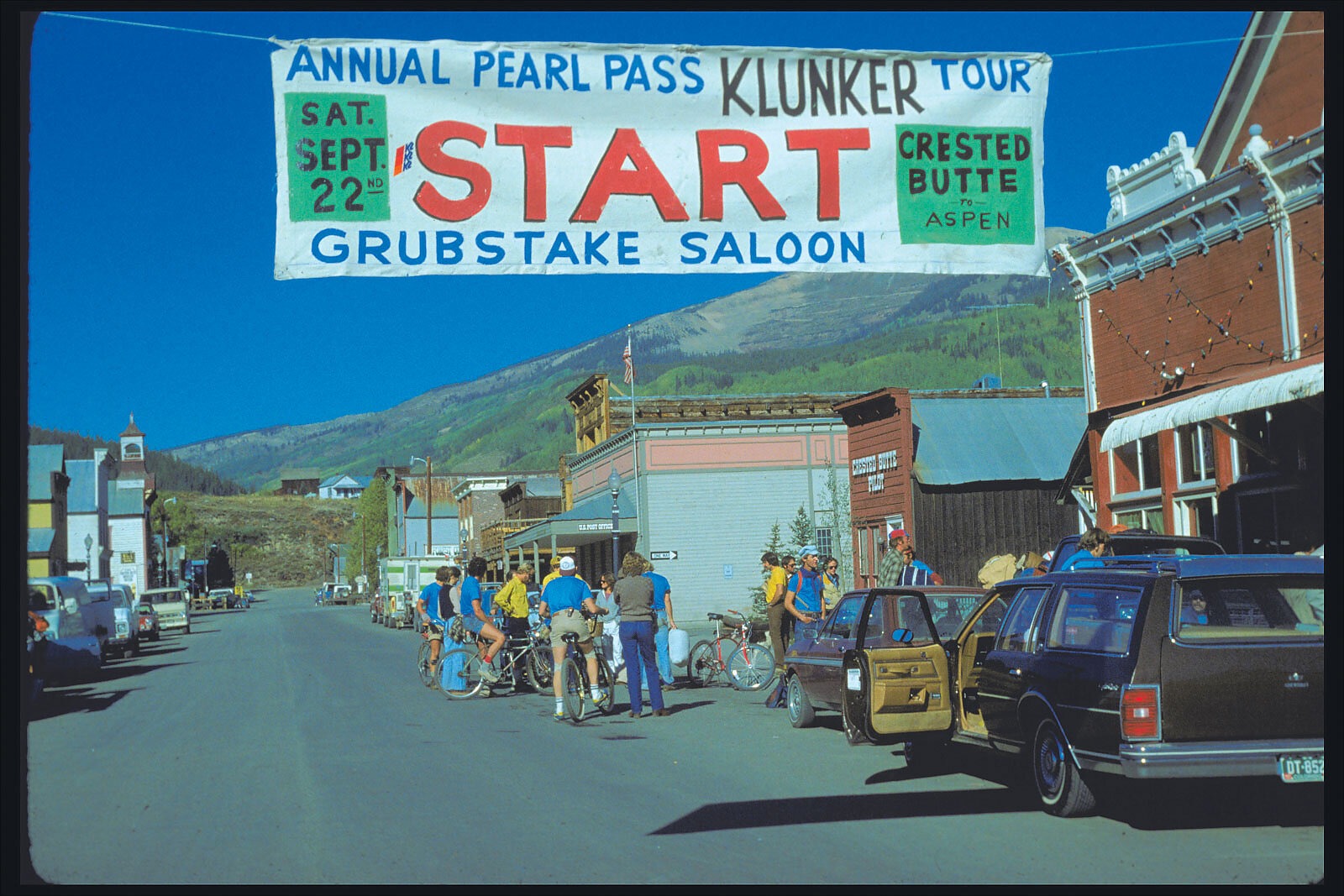

In the mid 1970s, a fabled group of Crested Butte ski bums and waiters and outlaws and daredevils, Cook included, organized what would become an annual group ride off the summit of 12,705-foot Pearl Pass , the high point between their town and Aspen. Cook hardly paints a picture of nobility when recalling the impetus.

“It was just guys trying to chase girls in Aspen,” he says. “Call it what it is: a couple adult beverages and guys chasing girls.”

They shuttled their 45-pound klunkers up the bumpy dirt road in a pickup truck that carried a bathtub in the bed. Then they pointed their wheels downhill and hoped for a happy ending. The occasion, of course, included a raucous campout in Cumberland Basin, kegs and all.

As is often the case when something special begins, word spread. Someone wrote a story that reached an equally fabled group of riders in Marin County, California, who by then were roaring down Repack Road on prototype bikes fashioned for off-road travel with drum brakes and grafted gears. The fire road was a legitimate fat-tire proving ground—it dropped 1,300 feet in 2.1 miles—but nothing so authentic terrain-wise as the Pearl Pass descent.

So, in September 1978, the California crew, including such pioneers as Charlie Kelly, Joe Breeze, and Gary Fisher, drove 1,100 miles east to Colorado with their more advanced bikes and joined the Crested Butte crew for their annual ride. Each of the visiting riders adopted a Colorado local’s bike that week and worked on it until midnight at Bicycles, Etc., slicking it up for the next day’s adventure.

“Those guys got here and saw the terrain and went, ‘Whoa, this is what we need,’” Cook recalls. “Yet the guys here looked at their bikes and said, ‘That’s what we need.’ So, they had the technology, we had the terrain. And the blend of that is really where the mountain bike came from.”

The sport, as it were, took off from there. Cook flew around in his friends’ planes scouting routes from above, and Crested Butte became the first international fat-tire destination. The town was at the center of almost everything related to mountain biking. Raleigh, then one of the world’s biggest bicycle manufacturers, launched a foursteed line of off-road bikes in 1983. Its premier model had Shimano XT components, weighed 28 pounds, retailed for $925 at the shop Cook owned with his older brother Steve—and was called, of course, the Crested Butte.

Specialized photographed the poster for its first Stumpjumper (tagline: “It’s a whole new sport”) on the stunning Lower Loop trail along the Slate River. Also in 1983, Cook and his future wife, Kay Peterson, founded the Crested Butte Mountain Bike Association—the world’s first mountain bike club. Today the organization maintains more than 450 miles of trail, including some of the best singletrack in the state. Cook and Peterson went on to found the Mountain Bike Hall of Fame, which called Elk Avenue home for 25 years until moving to Fairfax, California, in 2015.

Some of the same trails that made Colorado famous during those early years remain timeless classics, like the 8-mile Trail 401 descent off of Schofield Pass, the velvety smooth Doctor Park aspen ride into Taylor Park Campground, and the 19-mile whooping backcountry loop known as Reno-Flag-Bear-Deadman.

Before every Colorado town seemingly had its own world-class network, Dave Wiens remembers a leaner reality. Wiens, 58, a Denver native whose parents grew up on farms, had what he called “itchy feet to get out and explore” as a kid in the burbs. He went on to become a Hall of Fame racer who won the Leadville 100 six times, as well as a longtime advocate who has lived in Gunnison for 40 years. He started Gunnison Trails in 2006 and for the past five years has worked as the executive director of the International Mountain Bicycling Association (IMBA), which was founded in California but is based in Boulder.

Early in his career, Wiens competed in a 10-race series across Colorado. “There wasn’t much variety back then,” he recalls. “Fruita didn’t exist; Lunch Loops didn’t exist; Emerald Mountain in Steamboat didn’t exist; a lot of Summit County’s trails didn’t exist; Hartman Rocks was all game and livestock trails.”

The essence comes only in the moment, when you’re gasping for air at 12,000 feet, blitzing past yet another shimmering alpine lake, flowers as tall as your hip smacking your handlebar as you corner, their stamen exploding in your face so emphatically that you start to sneeze.

Then, simultaneously but with little coordination, webs of singletrack began popping up in various places around the state. Part of that was thanks to IMBA, which “gave mountain bikers the secret sauce, which was building relationships with land managers,” Wiens says. But another part was due to individuals—characters, really— who simply wanted more and better trails to ride. Consider the advent of Phil’s World, now a world-famous 45-mile network tucked in the southwest corner of Colorado near Cortez.

Phil Vigil, a Santa Fe, New Mexico, native who raced the first Iditabike in Alaska and worked as a medical records keeper at the Cortez hospital, started tidying up game trails in the late ’80s and early ’90s. The tracks were high-desert flow trails, not that the term existed back then, that maximized topography and terrain and didn’t involve big climbs or technical descents—perfect for the rigid and hardtail steeds of the time. Vigil, who died in late 2020 of a heart attack, didn’t like the renown he or his network attracted (and, in fact, he eventually stopped riding there entirely), but like a lot of Colorado’s original gangsters, he found a way to balance the yin and the yang. When his wife chided him for something unrelated, he’d flash a wide grin and quip, “Yeah, but you don’t have a World.”

Hartman Rocks, Wiens’ backyard network, evolved in a similar fashion and now features 50 miles of rolling singletrack that remains off the beaten path for many chasers of epic loops. It grew out of unmarked hoof paths into a spider web that satisfies everyone from Hall of Famers to 7-year-old grommets.

Wiens still travels all over the country to ride and preach the mountain biker’s gospel, sometimes in the company of his wife, 1996 Olympic bronze medalist Susan DeMattei. But he always relishes coming home.

“When people ask me if Colorado really is as good as it seems, I say yes. Because it has the whole package,” he says. “It’s the landscape, the way you feel, the breweries, the restaurants, the locals. That stuff isn’t important to everybody, but I do think it resonates with a lot of riders. It’s special here, and you don’t hear about people talking about other places in the same way."

It’s not uncommon, once someone experiences the distinction, for him or her to stay forever. Longtime Santa Cruz Bicycles pro Josh Tostado arrived from Maine in 1996, landing in Summit County. That summer he covertly borrowed his roommate’s bike and took it for a ride—his first taste of the feeling that would define his life for decades. Since then, he’s won four 24-hour national titles and dozens of endurance races around the country, while exploring more of its nooks and crannies on fat tires than probably anyone in modern history.

“Colorado can be a shit show, but if you avoid the places where everybody’s going—which is kind of a select few, and they’re really only busy at certain times—you’re good,” says Tostado, who is 46. “I love finding those little drive-through spots; nobody stops there, they just drive through. Like Alamosa, for example. It’s pretty much desert and a donut hole for snow, but I’ve done a 12-hour race there and there are tons of trails popping up, because locals are building and it’s really good riding.”

Tostado’s first career victory came at Montezuma’s Revenge—a 24-hour “mountain bike odyssey,” now defunct, that took place in a 50-person village under the Continental Divide and required racers to summit at least one 14,000-foot peak, epitomizing the sport’s hardman ethos for 19 years. Tostado is now (usually) based in Fairplay, an 1859 gold-mining town located a half hour south of Breckenridge; its 9,953-foot elevation isn’t ideal for year-round riding, but he has ample high-desert locales within a short drive from his house—Cañon City, Buena Vista, Pueblo—that often stay tacky through the darkest months. Factor in Fruita and Grand Junction a few hours west, and the menu gets longer.

“That’s what people don’t realize,” Tostado says. “The alpine is amazing, but really, you ride that for three months then it’s pretty much done. Yet rarely do you have a time during the winter when you can’t find dry dirt in the state of Colorado.”

"I’ll give up a perfect riding experience to have the views and that feeling of, I’m really small in this big world. And you get the best of both in Colorado."

—Sarah Sturm

And the farther you venture from the I-70 corridor that fast-tracks the metro population into the mountains, the more likely it is that you’ll have the trail to yourself. Nowhere is this more evident than the San Juan Mountains, one of the mightiest ranges in America, pocked with classic adventure towns to boot. Specialized rider Sarah Sturm, 32, moved to Durango from her native Albuquerque, New Mexico, to attend college and still hasn’t left. Not only does her backyard allow for massive training rides, but it also feeds her intellect.

“There’s an insane amount of history here; it’s almost impossible to do a big ride without seeing a super old mining claim,” she says. In fact, Sturm often designs her alpine loops around the rickety, abandoned haunts she can visit along the way. “When you see where these structures are built and what people did 100 years ago, it just puts into perspective how tough they were—and how soft we’ve gotten,” she chuckles. “It’s a humbling part of being in the mountains, and it gets me out of race mode. Riding here is not always about doing the fastest things.”

This is not to say that anyone in the San Juans concedes a world-class ride experience for a sightseeing tour. On the contrary, some of the best shuttles in the state are found in the triangular mecca framed by Silverton, Durango, and Telluride. Think: Molas Pass to Durango on the Colorado Trail, Graysill to Cascade Creek, Coal Creek, Engine Creek... the list goes on (and on).

“I’ve noticed visiting other destinations, like Bellingham, you have these incredible ride experiences, but you’re in the trees,” Sturm says. “Santa Cruz felt the same way. They’re sick trails and the experience is really dope. But I’ll give up a perfect riding experience to have the views and that feeling of, I’m really small in this big world. And you get the best of both in Colorado.”

She grins. “But don’t move here please. It’s way better in Santa Cruz and Bellingham.”

No route epitomizes the singular bounty quite like the Colorado Trail. Liz Sampey, 40, grew up riding the woods of Minnesota and didn’t realize mountain biking was a sport until she moved to Colorado when she was 17, after graduating high school early. Bored of going in circles, and craving adventure, Sampey bounced around the state—Fort Collins, Denver, Golden, Nederland, the Gunnison Valley, with intermittent stints in New Zealand and Europe—racing enduro and super D before switching to long-distance rides, in part to give in to what was available.

“If you’re a singletrack rider, you can find great trails all over the world, but you have to look for them,” Sampey says. “In Colorado, they’re just there. It has everything. I’ve ridden a lot of amazing places, and I love different parts about everywhere, but if you want to ride a long way on singletrack, you really can’t beat Colorado.”

Sampey has what she calls a “sordid relationship” with the Colorado Trail, yet describes it as nothing less than “iconic—one of the top three huge rides in the U.S.” She’s entered the 530-mile Colorado Trail Race four times but has never finished it. In 2018, her first attempt, she was leading the women’s field and on pace to set a course record when her hub exploded 35 miles from the finish. She tried running with her bike, but it wouldn’t roll, so she scooped up the broken parts and made it 14 miles before finally conceding. She has since completed the entire CT in stages, including during the summer of 2022, when she rode all the bike-legal sections (roughly 340 miles) and, in order to avoid the gravel-road detours, fastpacked the 130 miles of wilderness portions after locking her bike to a tree for her partner to pick up and shuttle to her next junction. It was a consolation of sorts, after another failed attempt at victory.

“I kind of got smacked on the CT this year during the race, because I got rained on for 12 hours two different times and didn’t have enough layers,” she says. “You’re never conquering shit out there. You just have to do your best and take what the mountains give you.”

Sampey now lives in a van (who in Colorado doesn’t?), bouncing between Durango, Salida, Carbondale, Rico, and Silverton. More than most, she understands and takes advantage of all that’s on offer in the state.

“Yeah it’s crowded, but you just have to be willing to go a little farther,” she says. “If you put in the work, you can ride all day or for days on end and not really see anybody. And the people you do see will be like you. I’ve done six-day bikepacking trips from Durango that don’t even touch the CT—all on singletrack.”

Creativity is key. Take, for instance, the 19-mile Sidewinder Trail, a beautiful point-to-point, moto-friendly singletrack outside of Montrose, as technical and rugged as it is mostly empty.

“No one knows about Montrose,” Sampey says. “But it’s one of my favorite trails in the state.” Her statement is bigger than Sidewinder, however. People may poo-poo the bounty for the crowds, but they’re missing the point.

“There’s still so much adventure to be had in Colorado,” she says.