A Sliding Scale Reaping The Rural Benefits In Southern Vermont

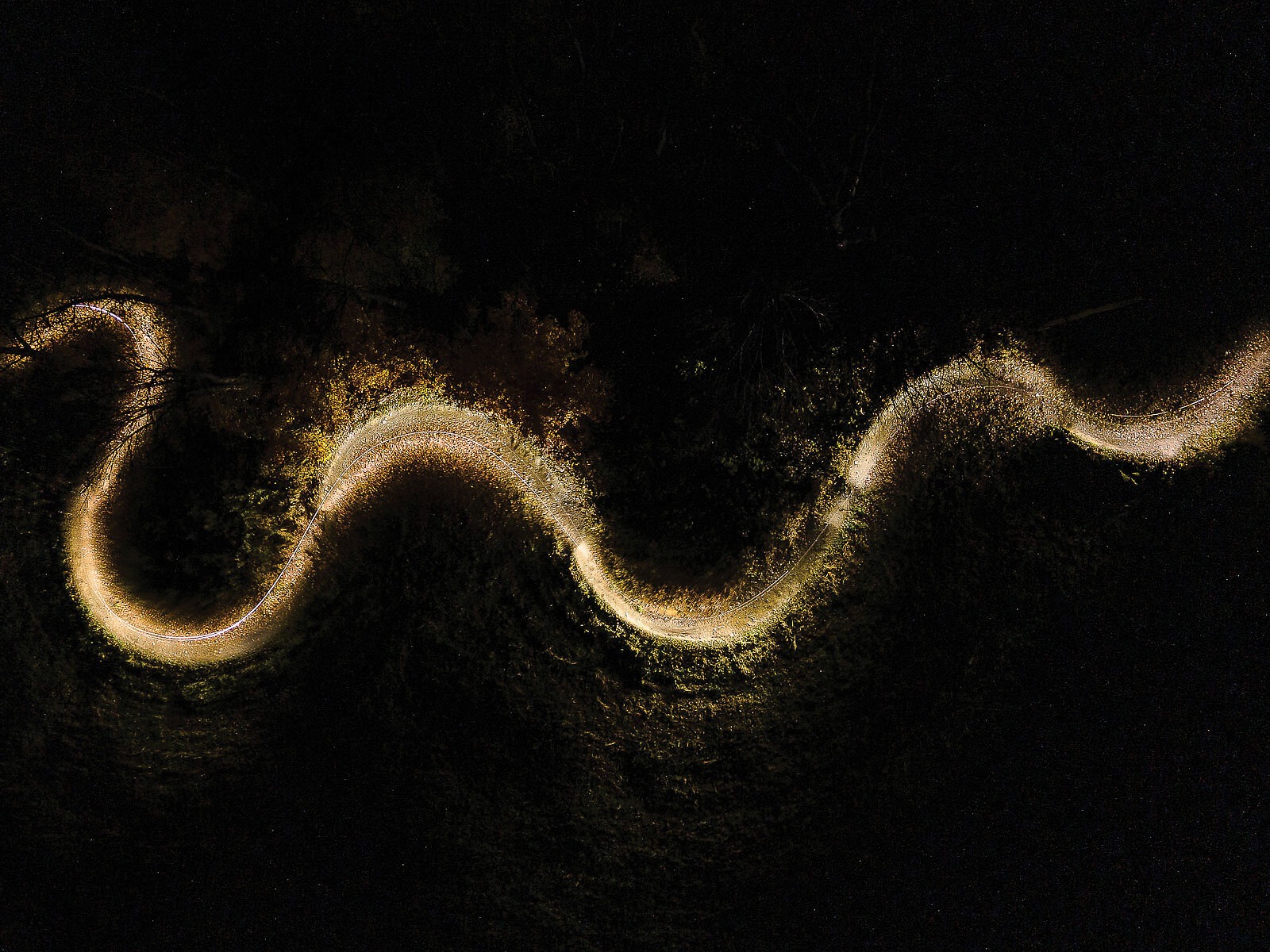

Words by Brice Shirbach | Photos by Brooks Curran

Small-scale society has many merits, and the entire state of Vermont is decidedly small-scale.

With a population of fewer than 650,000, a solitary international airport and only two interstate highways, the Green Mountain State is one of the country’s most rural. While its unemployment rates are among the lowest in the United States, so is the average wage—and the cost of doing business outstrips that of many other states.

Vermont has an almost mystical quality that can be felt the moment one crosses into the state from neighboring New York or Massachusetts. It’s not just the allure of the beautifully manicured farms that line the valleys between rolling green mountains. A ruggedly individualistic ethos pervades its tight-knit communities, and neighbors can be counted on to help each other during tough times. It’s a place where the impact of a person’s efforts can be felt immediately, and where homegrown industries such as maple syrup, ice cream and craft brewing can have a major economic impact.

And, for a growing number of communities—particularly in the state’s southern half—seemingly innocuous mountain bike trails are increasingly being viewed as commodities in their own right. At the epicenter of this phenomenon is the quaint town of Rochester, home to the Ridgeline Outdoor Collective (ROC), a 501c3 trail organization that is a chapter of both the Vermont Mountain Bike Association (VMBA) and the Catamount Trail Association. When the group was founded in 2013, it was initially named the Rochester/Randolph Area Sports Trail Alliance. After several years of operation, the scope of the group’s work expanded to include a broad swath of southern Vermont, including Pittsfield, so in 2021 its name was changed to the Ridgeline Outdoor Collective to be more inclusive of the many communities along the Green Mountain spine.

“The initial response [to the formation of the ROC] was a bit of a mixed bag,” says Angus McCusker, a Rochester resident and co-founder of the ROC. “We didn’t want to really come in and replace or take over what was already going on. We just wanted to add to it.”

Though all of the regional communities offer classic Vermont trails—with stunning dirt, an array of technical features and dense green tunnels—each of them has its own unique character that reflects the priorities of local trailbuilders. As with most of the country’s early trailbuilding efforts, the bulk of it happened largely under the radar, with builders in each community mostly keeping to themselves. The Rochester-area trails were defined by old-school tech, with a scene that centered around Green Mountain Bikes, the town’s decades-old bike shop. In nearby Pittsfield, Matt Baatz had for years been quietly building out one of Vermont’s most technically demanding trail networks, the Green Mountain Trails. Many of the trails between Randolph and Rochester had originally been designed by community leader Zac Freeman and a handful of other clandestine builders. But despite their close proximity, the three communities were siloed from each other in their approach to their respective trails.

Shortly after its inception, ROC began working to connect these communities in both a symbolic and financial sense, with its 501c3 status allowing it to receive donations and qualify for publicly funded trail grants. In recent years, such funding has allowed local trailbuilding efforts to diversify from the early hand-built efforts of Baatz and Freeman to modern, machine-built flow lines sculpted by the likes of northeast Vermont stalwart Tom Lepesqueur.

While such efforts have elevated the status of southern Vermont’s trails and brought the building communities closer together, for ROC, this is just the tip of the iceberg. McCusker, the group’s current executive director, also heads the Velomont Trail project, an ambitious plan to connect 19 trail networks from the Massachusetts border to as far north as Stowe via a system of huts. Thanks to ROC’s involvement, Rochester, Randolph and Pittsfield are all playing a major role in the Velomont Trail’s development.

“Angus and Caitrin [Maloney] have been the leaders of Velomont and are beyond instrumental to its success,” says Ben Colona, who has served as president of the nearby Killington Mountain Bike Club (KMBC) since its formation in 2015. “The passion that those guys have, along with plenty of other people, is really inspiring. They are able to show everyone that Velomont is a good idea, and that it’s very attainable.”

Prior to Colona’s current job as the owner of Killington’s Base Camp Bike and Ski shop, he spent 15 years working for Killington Ski Resort and has become an extremely active member of the resort community of 1,400 people.

“I can’t say I’ve seen a stronger, more tight-knit community,” Colona says. “Going out to dinner on a Tuesday or Wednesday night, you’re going to pretty much know most of the people in the restaurant and they’re all going to say hello. Everybody gets behind whatever happens to be going on.”

Nestled in the heart of the Green Mountains, Killington Ski Resort is one of New England’s most popular, attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors each year. Killington Peak is the state’s second tallest summit, looming where the Green Mountain range’s spine is at its most impressive. While the resort has long been popular with skiers and snowboarders, during the warmer months it's one of the country’s preeminent bike parks, served by three high-speed lifts and featuring all manner of trails—from steep, jarring old-school downhill to beautifully manicured jump lines. What’s more, a large percentage of the bike park is dedicated to beginner-friendly terrain, making it attractive to riders of all skill levels.

Killington Ski Resort has earned plenty of fans over the years, and the KMBC has been working diligently to provide locals and visitors alike with additional riding opportunities to complement what is inside the park.

“It really stemmed from the community addressing a need,” Colona says. “And a few of us were obviously very focused on the mountain bike side, especially with the growth of the resort. As the resort grew, they began removing the old cross-country trails and converted that terrain into downhill throughout the Snowshed and Ramshead areas.

“SEVERAL OF US FELT THAT DOWNHILL AND CROSS-COUNTRY

TERRAIN KIND OF GO HAND-IN-HAND, SO AS WE LOST

CROSS-COUNTRY ON THE MOUNTAIN, WE NEEDED TO FIND

A NEW HOME FOR IT. AND THAT’S WHERE THE THOUGHT OF

THIS KILLINGTON MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB CAME FROM.”

—BEN COLONA

“Several of us felt that downhill and cross-country terrain kind of go hand-in-hand, so as we lost cross-country on the mountain, we needed to find a new home for it,” Colona adds. “And that’s where the thought of this Killington Mountain Bike Club came from.”

About the time the KMBC filed for its 501c3 status, 20 miles east along U.S. Route 4 another group of Vermonters was looking to do the same for their small community. The town of Woodstock was chartered 15 years before the United States declared its independence from Great Britain and, save for a brief lull in the 19th century, it has remained a quintessential Vermont community, with scenes that might as well be straight out of a Norman Rockwell painting.

As with Killington, tourism is the lifeblood of Woodstock, and its mom-and-pop ski hill, Suicide Six, is one of the country’s oldest. With scores of artisan bakeries, art galleries and high-end B&Bs lining the town’s spotless roads, Woodstock stands out as one of Vermont’s most affluent communities—and its polished presentation reflects that.

“I think Woodstock sometimes has a ‘fancy high-end’ stereotype which certainly exists, but I would say that my perception of it as someone who lives here is we’re community-oriented people who care about where we live,” says Seth Westbrook, a mountain biker and trail advocate who grew up about 25 miles north of Woodstock. “It’s interesting because it’s not as in your face about its outdoors as you might find in plenty of places out west. Around here it’s a bit more of an understated part of the fabric of the community.”

A few years after graduating from college in Burlington, Westbrook answered the deep-powder call of the American West, bouncing back and forth between Eugene, Oregon and Hailey, Idaho. When he and his wife welcomed a daughter in 2010, they decided to head back to Vermont to be close to family and put down their roots in the Woodstock area.

“We were mulling over whether to move to Montpelier or Stowe, or somewhere farther north,” Westbrook says. “But the more time we spent in Woodstock, the more we were like, ‘Yeah, this is really good.’”

For Westbrook and many of his friends, a huge part of Woodstock’s appeal is the trails. Surrounded by three superb riding zones—Suicide Six, Mount Peg and the Aqueduct Trails—each system has its own distinct flavor. But all of them share one fundamental ingredient: dark and robust dirt. While Vermont is renowned for having some of the country’s finest dirt, Woodstock might have the very best of it. For decades the area was home to disparate pockets of riders, some quietly scratching in secret loamers, others driving west to Killington or south to Mount Ascutney, or simply exploring the Nordic trails around Mount Peg.

By 2015, however, Westbrook and his friend Matt Stout began to see the need for a well-organized trail association that could help preserve the area’s existing trails and drum up support for the construction of new singletrack.

“We were hitting up as many people as we could and just trying to spread the word organically,” Westbrook says. “We ended up signing the landowner agreement with the Aqueduct and then that next summer we built a pretty substantial bridge and a new trail. And pretty quickly people were kind of like, ‘Oh, OK, this is cool.’”

Since its inception, the Woodstock Area Mountain Bike Association has been responsible for the development of trails across all three of the region’s main riding networks. And while the scale of the mountains that surround Woodstock doesn’t match what Killington or Rochester have to offer, the quality of the riding might be unparalleled.

“The dirt is only part of the secret sauce,” Westbrook says. “Rob and Gavin Vaughan are the other part. Those two, with their eye for design and magic touch, really set the tone for the region. And they’ve contributed massively to the whole vibe of the area, especially at Aqueduct and Mount Peg.

“MAYBE THAT’S WHAT SOME PEOPLE FROM OUTSIDE THE AREA LIKE SO MUCH ABOUT VERMONT. IT’S A SMALL-SCALE SOCIETY, AND A PERSON WITH VISION, ENERGY AND RESPECT FOR OTHERS CAN DO A LOT OF GOOD HERE.”

—CHRIS SMID

“I think our terrain limitations have had a positive impact on our approach to building trails,” Westbrook adds. “We’re always looking to maximize the fun factor and squeeze every fun bit of terrain we can into a trail.”

Though Vermont is overwhelmingly rural, there is a corridor of communities that draws more visitors and reaps the benefits of a tourism economy. This has created significant income inequality between towns, and for those that find themselves on the outside looking in, that inequality can feel like a gulf.

“You’ve got these sections of Vermont that are very well to-do, and then there’s the rest of the state,” says Chris Smid, co-owner of the Poultney, Vermont-based roofing company New England Slate. “That’s one of the conundrums for Vermont as a whole. If we’re going to base our whole economy on tourism, we have to have to find a way to do a little better at providing a livable wage to the local folks.”

In addition to the demanding job of running a roofing company, Smid serves as president of the Poultney-based Slate Valley Trails organization, which oversees a rapidly growing network on the state’s southwestern fringes. Bordered to the west by New York, Poultney lacks the tourism-driven economy of many other Vermont destinations. But it’s loaded with another valuable resource: slate, the homogenous metamorphic rock that has made this northern edge of the Taconic Mountains a mining hotspot.

Until recently, the local economy’s dependency on mining was partially offset by the presence of Green Mountain College, which provided an employment alternative for the town of 3,200 people. Founded in 1837, the liberal arts college was renowned for its focus on environmental literacy, but in 2019 it closed its doors due to lack of funding. Following the closure, residents began searching for other sources of revenue, and some took a hard look at what mountain bike trails can mean for a community on the brink of economic ruin.

“Because of our geographic separation from other parts of the state, we’ve been a little slower to develop,” Smid says. “We’re choosing our path forward carefully and want to maintain the connection to the local community and kind of keep it real. We want to have visitors and have great trails and have great outdoor recreation, but we also want to avoid becoming another stop on the circuit for out-of-staters coming in for a few days or a week at a time.”

In keeping with this goal, the Slate Valley Trails organization is not actively promoting its trails to the greater mountain bike community in an effort to be mindful about the town’s development. But Poultney’s bedrock of slate lends itself to brilliant mountain biking, and its untapped potential is rapidly being recognized. Thanks to donations from private benefactors, several miles of new trails have been built along hundreds of acres of private property.

Despite this rapid growth, the Slate Valley Trails group remains as dedicated to the integration of the trails into the community as it is to stacking up miles of rocky singletrack. The organization is working with the Poultney Chamber of Commerce to better connect with local businesses and cooperating with the township to develop trailhead and parking infrastructure. All of this development is being complemented by the work of two of Vermont’s building and advocacy luminaries: trailbuilder Hardy Avery and influential environmental advocate Caitrin Maloney.

“When Hardy and Sustainable Trailworks came down to start building at Slate Valley Trails, everyone was super excited,” Smid says. “Hardy and Caitrin were known entities. They brought a lot of positive attention to the trails. Hardy is well respected as a builder and had done such a good job in other parts of the state, so getting him here a few years ago was a fantastic start.”

“THAT’S ONE OF THE CONUNDRUMS FOR VERMONT AS A WHOLE. IF WE’RE GOING TO BASE OUR WHOLE ECONOMY ON TOURISM, WE HAVE TO FIND A WAY TO DO A LITTLE BETTER AT PROVIDING A LIVABLE WAGE TO THE LOCAL FOLKS.”

—CHRIS SMID

For her part, Maloney had previously worked for Stowe Land Trust, a prominent conservation group, and she had considerable experience with nonprofit management and board development. She applied that experience to helping Slate Valley Trails with strategic planning and fundraising.

Maloney and Avery were so impressed by the area’s potential that they personally invested in it, with Avery’s company, Sustainable Trailworks, buying land and contributing to further trail development.

In addition to working down here and building the trails, they now own land and are developing their own business right here in Poultney,” Smid says. “They’ve kind of bought into the long-term vision of Slate Valley Trails and decided to make this their home and see this place as a place they want to live.”

For Smid, this type of personal investment and community buy-in are what makes Vermont such a special place to live, ride and build trails.

“Being a Vermonter means respecting other people and working together in a very direct and personal way,” Smid says. “Maybe that’s what some people from outside the area like so much about Vermont. It’s a small-scale society, and a person with vision, energy and respect for others can do a lot of good here.”