The American Alps Peaks, Valleys and World-Class Singletrack in Washington's North Cascades

Words by Sakeus Bankson

They were scattered on both sides of the dusty, washboard trail like cast-off plastic bones, their cylindrical shapes bulging from the North Central Washington heat.

Most the water bottles were clear or white, and we searched through the torn-up mat of ponderosa needles for the odd spots of color. Those were the best. They were usually from hallowed locales like Moab or Durango. Places we wanted to go. Places we dreamed of riding.

It was 2001, in the tiny tourist town of Chelan, WA. The bottles were remnants of a regional mountain bike race held at the local Echo Valley ski hill, shaken from the racer’s frames on this particularly bumpy section of trail. While neither myself, my brother, nor our friend Cody actually needed any bottles, for three small-town, teenage wannabe mountain bikers, they were tokens of a larger, more exciting world, a taste of cutting edge in our backwoods bubble.

Or that’s what we thought at the time. With our attention on our recycling bin, we missed one key detail: we forgot to look up. If we had, we’d have realized the surrounding terrain was some of the most impressive in the country: the North Cascade Mountains, nicknamed "the American Alps" for their archetypal peaks and Sound of Music-esque alpine meadows. Even then they were packed with trails of all types, a dreamland for any ambitious rider with a taste for an adventure. We just hadn't noticed yet.

Nor had the larger mountain bike industry (with a few exceptions). That notoriety was still to come. When it did…well, our North Cascades “backwoods bubble” would change the sport, traversing highs and lows as unique and world-class as the terrain over which it traveled.

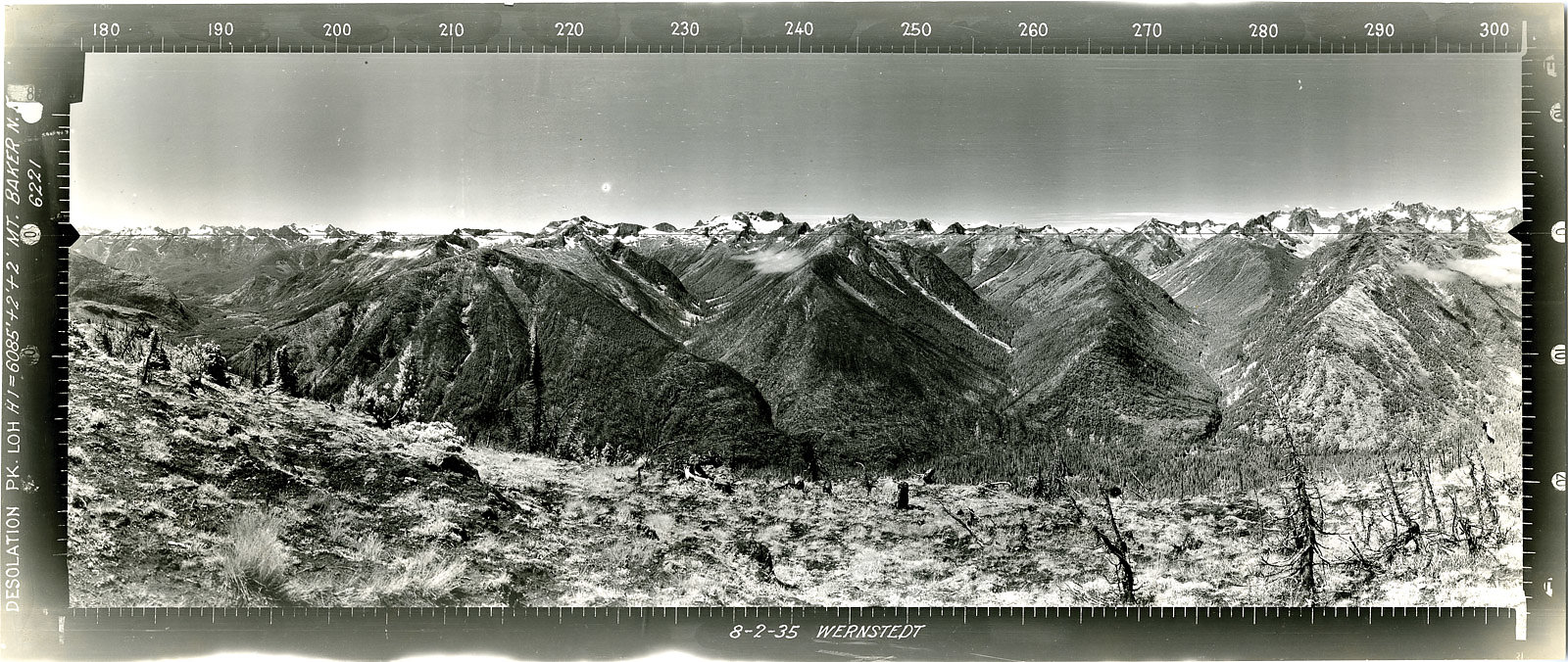

A part of the larger Cascade Range, the extent of the North Cascades depends on who you ask. Generally, the term encompasses the mountainous terrain north of Snoqualmie Pass to the Canadian border to the east by the Okanogan and Columbia rivers, and the west by Puget Sound, an area shy of about 11,500 square miles.

Between those boundaries is a world of extremes, in almost every aspect.

Weather is the most obvious. Seattle, near the southwestern corner, sees more than 150 rainy days a year, but—despite its reputation—receives just over 37 inches of annual precipitation, a mere six inches more than the US average. Snoqualmie Pass, at the southern crest, receives nearly 100 inches, while Wenatchee, at the eastern corner, regularly experiences temperatures over 100 degrees Fahrenheit and sees only 9 inches, technically making it a desert. In Bellingham, at the northwest corner, the lowest temperature on record is 19 degrees—67 degrees warmer than Winthrop’s historical low of -48 F, a state record.

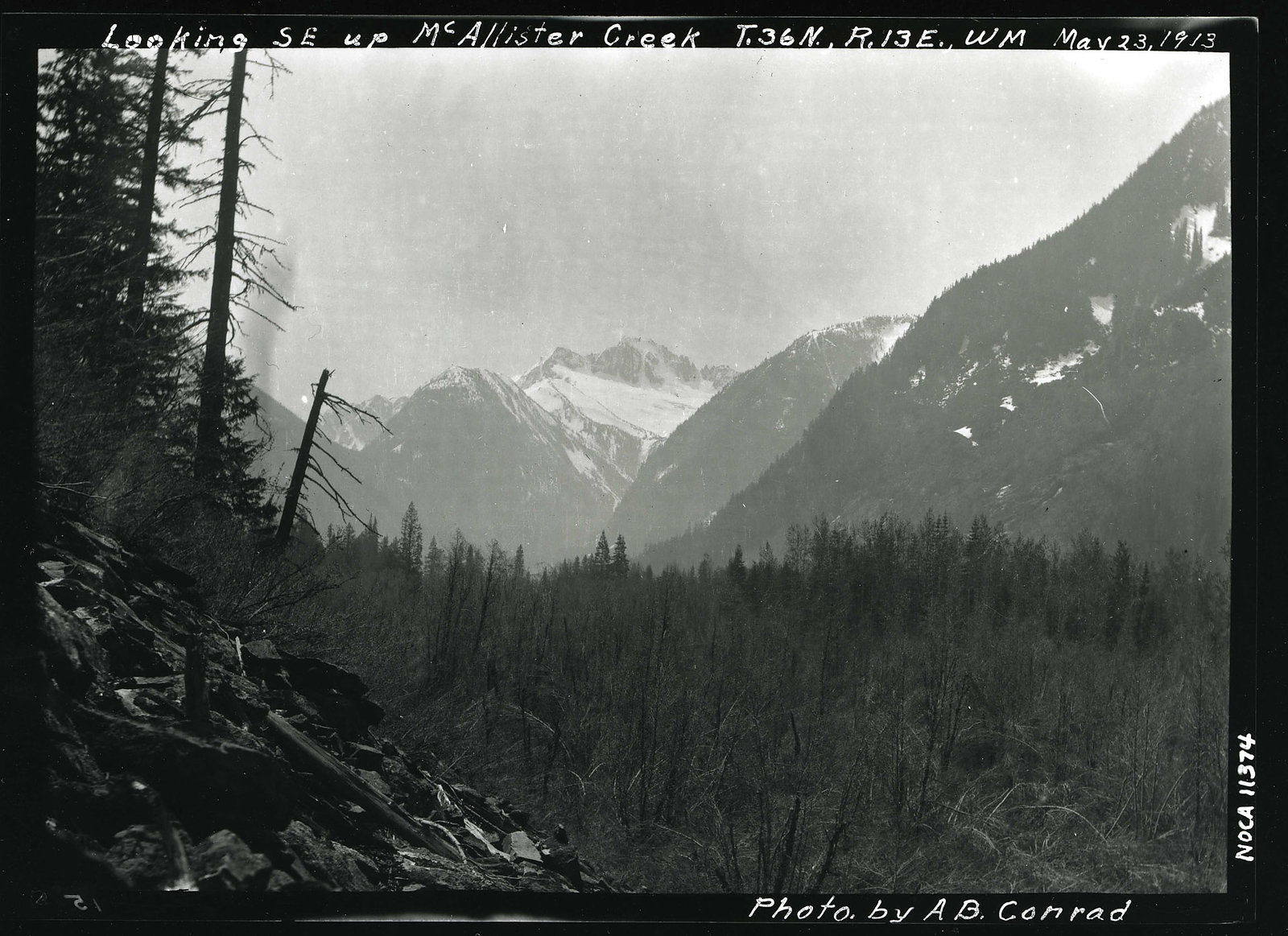

The most stunning contrast, however, are the mountains—not the elevation, but the relief. Most of the North Cascades’ summits barely scrape 6,000 feet but burst from near sea level, climbing thousands of vertical feet in a fraction of the distance, before plunging again into precipitous valleys. The most extreme is Lake Chelan, a narrow, 50-plus-mile-long inland fjord cutting into the range from its eastern edge. From the top of the highest abutting peak, the valley wall drops an uninterrupted 9,731 feet in three horizontal miles before reaching the lake’s 1,486-foot-deep bottom, nearly 400 feet below sea level, making it the deepest gorge in North America.

Because of the vast geographic differences, the North Cascades are home to deer, black bear, grizzly, lynx, cougar, wolves, marten, wolverines, elk and even moose. Immense forests of old-growth cedar, hemlock and Doug fir grow on the western edge, ponderosa and sage on the eastern, and cottonwoods, larch and sub-alpine fir across the region, depending on the elevation. Climbing upward, vast clumps of glacier cling to the craggy summits—a lot of glacier, more than the rest of the contiguous US combined.

Unlike its European counterparts, much of the American Alps are essentially a blank zone on the map, at least when civilization is concerned. There are only three roads traversing the range, the northernmost of which—Highway 20, or the North Cascades Highway—is buried under snow for five months of the year. A train didn’t cross the North Cascades until 1893, via a series of steep switchbacks over Stevens Pass. In 1890, the railroad built a tunnel under the pass to avoid avalanches, with tragic results: in 1910, an avalanche destroyed two trains and killed 96 people, leading to the construction of a deeper tunnel farther down the pass. The 1910 avalanche disaster remains the deadliest in US history.

Dangers aside, by the turn of the 20th century local alpinists were already bent on conquering the range’s imposing terrain. The Mountaineers Club, an early climbing, outdoor and conservation group, was established in Seattle in 1906. Eddie Bauer opened his first store in 1920, selling the original quilted down jacket. Lloyd and Mary Anderson founded REI in 1938, to supply the local cadre of alpinists that now included legends like Fred Beckey and Jim Whittaker. Beatnik author Jack Kerouac and poet Gary Snyder both spent time manning USFS fire lookouts, and during the backpacking boom of the late 1960s and 1970s, iconic companies like MSR, Therm-a-Rest, and Outdoor Research upended decades of traditional gear standards.

As the 1970s rolled along, the country’s sleepy, northernmost corner was already an established pioneer for outdoor recreation. It’s hallowed reputation in the mountain bike world, however, would take a few more decades.

It’s on the North Cascade’s mellower shoulders that mountain biking first found fertile ground. The range’s dramatic nature, which made the range so renowned for mountaineering and hiking, posed problems for any vessel with wheels: combining gravity with extremely steep, rocky and root-covered slopes isn’t an equation for success. Or a good time.

The relatively remote location didn’t help with the influx of new trends, either: in 1980, Washington’s entire population was a mere 4.1 million, 2 million of which were clustered around Seattle. But by the 1980s, there were plenty of locals who’d discovered the wonder of “fat tire” bikes on their own: a crew in the Methow Valley were already exploring trails the USFS would deem off-limits in 1984; cyclists in Bellingham were cutting singletrack in the thick woods on nearby Galbraith Mountain; and riders in Seattle were grunting up fire roads on Tiger Mountain.

It may not have been a scene to rival hotspots like California, but by the late 1980s there were enough mountain bikers in the North Cascades to spark another familiar, less savory aspect of the sport: the fight for trail access, as negative interactions with hikers and land managers became increasingly frequent. Threatened with extensive closures, mountain bikers across the Cascades coalesced to save their trails.

In Bellingham, Jim “Sully” Sullivan had already seen such battles around his former home of San Francisco, so in 1986 he and a group of core Bellingham riders founded Whatcom Independent Mountain Pedalers (WHIMPS). Along with protecting existing trails and promoting the sport in the community, WHIMPS coordinated with both public and private land managers to develop trail building and use guidelines with (relatively) surprising success. Meanwhile in Seattle, the Backcountry Bicycle Trails Club (BBTC) was established in 1990 to advocate for access in the area. Just three months later they held their first trail work party, on Tiger Mountain, and over the next few years they presented land managers with a trail construction guide, held events, and—of course—built more trail.

Despite plenty of struggles, by the mid to late 1990s mountain biking was on the rise across the state. A few bike companies sprung up, such as Curtlo, a frame builder in the Methow, and ZeroFlex brakes in Duvall. The Seattle-based Bicycle Paper, founded in 1972, was soon featuring nearly as much mountain bike content as road, with ads for bike shops, classes, gear and a surprising number of cycle-accident-specific lawyers from across the region. The Washington-Idaho-Montana MTB Series (WIM) organized events and notoriously challenging races, one of which was described in a 1995 issue of the Bicycling Paper as “the gnarliest and most mountain biki’nest course many of them had or would ever compete in.”

That wasn’t just a locals’ view, either. When Snoqualmie Pass hosted a UCI World Cup DH in 1998, it was described in the UCI’s press release as “meter for meter, this has to be the most challenging course yet devised for World Cup Racing.”

Unfortunately, this rapid but quiet boom took somewhat of a bust by 2000. Some of the 1990s hype survived, events like Leavenworth’s Bavarian Bike and Brews Festival, which will celebrate its 21st anniversary this year, and the Wednesday Night World Championships XC race, which still goes down every week in SeaTac. Advocacy organizations like WHIMPS, BBTC, and Wenatchee Valley Velo—which started in 1998 as a replacement for the late Wenatchee Wheelman—have only grown and continue to drive the sport.

But many players either died off or faded into ghosts of their former glory, especially east of the Cascades. The Methow Valley MTB Festival, home of the infamous “Boneshaker” DH race, was a must-attend during the ‘90s and early 2000s, but by 2010 attendance had slimmed enough that it was rebranded the Methow Valley Bicycle Film Festival in hopes of reigniting interest. The Chelan MTB Festival, which had once held XC, DH and dual slalom races, was shuttered in 2005 along with the WIM series. As for the venue’s trails? They were torn down by the USFS shortly after, buried under pine needles with the abandoned water bottles.

At the same time on the other side of the mountains, a huge development was going down in Bellingham. In 2002, the Trillium Corporation bought 3,600 acres on Galbraith Mountain, encompassing some of the community’s most prized singletrack. Rather than battle over access, WHIMPS—soon to be the Whatcom Mountain Bike Coalition (WMBC)—and Trillium sat down together and negotiated a landmark land-use agreement that both preserved access and made WMBC steward of the mountain’s trail system.

All of that was once again put in limbo at the end of 2009, when Trillium ceded the land to Polygon Financial. When Polygon didn’t guarantee future access, the community came out in such force that the company decided to renew the land-use agreement. When Janicki Logging Company began timber harvesting in 2010, they did so in cooperation with WMBC.

There were losses alongside the successes, such as when the Department of Natural Resources shut down the prized North Fork trail system, a shuttle-access, DH-centric network near the Mt. Baker Highway, in 2012. But there were wins too, and big ones. In 2013, the DNR transferred over 8,800 acres of forest surrounding Lake Whatcom to the county, to be set aside for watershed preservation and non-motorized recreation—bikes included.

Momentum was building in other parts of the state as well. For BBTC, what started with the success of the I-5 Colonnade urban mountain bike park hit full stride in 2010 with the even more popular Duthie Hill Mountain Bike Park, and in 2012 the organization—which had rebranded as Evergreen Mountain Bike Alliance in 2008—added four new chapters that literally spanned the state. Now they have eight chapters with a membership nearing 5,000; impressive in its own right, but even more so considering 99.8 miles of the trail under construction is completely self-funded by members and through trail campaigns.

New events and races seemed to be springing up on both sides of the mountains, while old ones got revised and refreshed. In 2011, the NW Epic Series ran a XC race at Chelan’s Echo Valley, an event that’s returned every year since. In 2014, the Methow Chapter updated the flagging Bike Film Festival with the Methow Singletrack Solstice; a year later, the inaugural Dark Side Festival—a collaboration between Evergreen and Wenatchee Valley Velo—premiered at Squilchuck State Park, former home of the “Squilchucker” stop of the WIM MTB series and current home of the Mission Granduro, a burly 45-mile race with nearly 10,000 feet of climbing.

The heavyweight, however, is the Cascadia Dirt Cup. The Enduro series debuted in 2013, and its venue lineup now includes zones like the Chuckanuts, Tiger Mountain, Olympia’s Capitol Forest, and—for the first time this year—Raging River near Snoqualmie, one of Evergreen’s newest ride centers.

The Dirt Cup is a serious competition, yes, but more in a flannel-clad, “hold my beer while I send this stump to flat on my klunker” sort of way. It’s a distinctly Northwest vibe, one that Transition Bikes and Kulshan Brewing summarized in their collab beer. “Party in the Woods,” it’s called, and the official release event was—no surprise—a huge party and group ride on Galbraith.

The North Cascade bike scene has hit full crescendo in the past year, one that straddles the range and has resonated across the country. Relationships with land managers are some of the best out there, be it with the USFS, DNR, or city and county officials, and it seems every town has some form of trail system and advocacy group, both of which are undoubtedly growing. In Roslyn, it’s the Community Forest; in Winthrop, it’s Sun Mountain; in Leavenworth, Rosie Boa and Ski Hill; and for Yakima, it’s Rocky Top. And those are just a few.

In Bellingham, August 2018 heralded a victory three decades in the making: a year after Galbraith Tree Farm LLC purchased the 2,240 acres containing the city’s prized trail network, the company, the City of Bellingham, and the Whatcom Land Trust reached an agreement that preserves public access “in perpetuity”. Some conflict remains, true, but obstacles are far less daunting when everyone is pedaling in the same direction.

And as for Chelan? On pretty much any summer Sunday at Echo Valley, you’ll find a core group of area riders barbecuing after their weekly group ride or build day on some of the surrounding USFS land. One of those is Bob Knauss, a renowned machinery operator who has volunteered countless hours knocking in trails like Waterbar Heaven—the same Bob whose son, Cody, once grubbed in the pine needles with me and my brother.

Cody now lives in Colorado, an hour and a half from Durango, and regularly rides the same trails we dreamed about as kids. I’ve ridden them as well. But whenever we talk mountain biking, Durango is a cursory mention, and Moab hasn’t come up in years. But even Galbraith sees only occasional coverage.

Instead, we scheme our next chance to ride two favorite all day epics, Angel’s Staircase and Pot Peak. The funny thing? They’re both visible from that water-bottle strewn stretch of singletrack. It took two decades, but we finally looked up and what we saw was the stuff of dreams.