After the Storm From Adversity to Unity in Hood River

Words by Elle Ossello | Photos by Alexandra Erickson

When an historic winter storm wreaked havoc on the Hood River Valley in January 2012, the mountain bike community watched in frustrated horror as destruction to surrounding forests mounted.

For days, wrist-sized branches coated in thick layers of ice sagged and eventually snapped, the noise echoing like gunshots across the frozen town.

Dispatchers worked day and night fielding calls about downed electrical lines and splintered power poles. The moment the icy roads became remotely navigable, a handful of anxious trailbuilders, mountain bikers and county forest managers made a beeline to the trails to see what was left.

“I went straight to Grape Smuggler,” trailbuilder Gary Paasch recalls. “I was crushed. Huge trees were thrown across the trail. If you didn’t know what you were looking at, it was hard to even tell where the trail was. I knew I would never rebuild Grape Smuggler back to what it was. The county was going to log it, and my heart wasn’t in it to re-create the trail that I worked on for the better part of 10 years. But deep down I knew there was something bigger that was coming. I just couldn’t see it yet.”

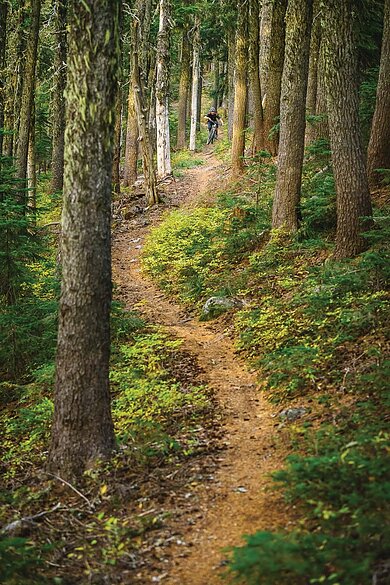

The devastation wrought by that unforgettable storm proved to be a pivotal moment that forever changed what it means to be a mountain biker in the small town of Hood River, Oregon. While many people associate the Pacific Northwest with temperate rain and mild golden sunshine, the Columbia River Gorge, with its ragged basalt cliffs and rocky scars left by the colossal river that runs through it paints a picture of a Mother Nature who isn’t quite so friendly. But her wrath is the very thing that laid the foundation eons ago for the rocky chutes, rooty tech and freeing flow for which Hood River’s most renowned trail system, Post Canyon, is known.

“I’ve only been involved for four years,” says Tim Mixon, president of the Hood River Area Trail Stewards (HRATS). “My kids were grown and I found myself with a lot of time on my hands. For years when they were growing up, I would sneak in a ride when I could, sometimes guiltily riding right through a trail work party.”

These days, Mixon is more than making up for lost time, working tirelessly in his complicated advocacy role. His plate seems impossibly full. Yet he’s unceasing in his drive to understand the complex needs of a diverse and passionate mountain bike community, while also balancing them against the agenda of the county forestry department, which primarily values Post Canyon for its original use as a tree farm.

“I was super annoyed with the 2016 presidential election,” Mixon recalls. “I wanted to do something that mattered. So I remember thinking, ‘Screw it, I’m going to act locally,’ and I raised my voice.”

Soon after, Mixon started showing up regularly to HRATS meetings and joining the animated discussions about equipping trailbuilders with resources and engaging the community in fundraising and trail work parties. But perhaps his biggest challenge is serving as an unofficial liaison between impassioned local riders and the county officials that manage Post Canyon’s timber resources.

Mixon is the kind of person who inspires action. If you find yourself walking into Dirty Fingers Bike Shop for a weeknight beer, odds are he’ll be there engrossed in a conversation about a legislative nuance or an interpersonal dynamic between trailbuilders. He has a way of untangling the small knots that converge to form a seemingly unconquerable obstacle. It takes wisdom and experience to focus on details without losing the big-picture goals, and Mixon does it in a way that is effective and personable.

These are traits Mixon shares with the late Matt Klee, the founder of HRATS and legendary champion of a vision that guides the organization to this day. Klee established HRATS in 2012 in an effort to unite impassioned riders and once-rogue trailbuilders. His timing was certainly less than coincidental. Although the seeds had been planted before the winter storm that took out Grape Smuggler, the scale of destruction and corresponding swiftness with which the county began salvage-logging throughout Post Canyon shifted the effort into overdrive.

Klee was widely loved, and had a unique ability to bring people together, even when they had dramatically opposing viewpoints. Mixon shares these attributes, and it’s clear that much of his success lies in his knack for understanding the validity of arguments from both the mountain bike community and the forest service.

“I just don’t think the county understands how people need these trails,” Mixon says. “The timber industry is a dying thing and yet Doug [Thiesies, the county forest manager] has this job that is the lifeblood of the county. The logs he pulls out of Post Canyon become 30 percent of the Hood River County general fund. He’s gonna protect that, and he should be.”

“IT’S EASY TO GET FRUSTRATED, BUT ANYTIME SOMEONE GETS TOO RILED UP, I SAY, ‘IF YOU WANT TO COME UP WITH $3 MILLION A YEAR THEN WE CAN HAVE A CONVERSATION ABOUT NOT CUTTING DOWN TREES.’ IT GETS SILENT PRETTY QUICKLY.”—Tim Mixon

“It’s easy to get frustrated,” he adds, “but anytime someone gets too riled up, I say, ‘if you want to come up with $3 million a year then we can have a conversation about not cutting down trees.’ It gets silent pretty quickly.”

At times, the tension between the Hood River County Forestry Department—a small office staffed by six—and the local trailbuilding community is palpable.

“There were over 40 people at the first trail committee meeting after that ice storm,” remembers Doug Thiesies, the county forest manager. “I had to tell them, ‘You can’t go up there and buck every log. You have to be patient.’”

Thiesies recounts the challenge of pacifying an agitated community anxious to prevent the logging and inevitable destruction of its trails. “From a forest health standpoint, we had to lay them out,” he says, adding that at that point, the importance of the trails to those local riders couldn’t be a factor in his decision-making.

As the full-fledged salvage logging operation ensued across the entirety of Post Canyon, HRATS came together with some of the most-established and well-respected trailbuilders and community leaders to figure out what was next for the trail system.

Long before there had been any formal acknowledgement of mountain biking in Post Canyon, there was bountiful evidence of the work of trailbuilding legends such as Antoine Chesaux (the namesake of Antoine’s Ridge), Jake Felt, Douglas Johnson, Dave Bisset, Jeff Blackman, Chico Bukovansky and many others. Among the most notable is Jimmy Thornton, who is known for a handful of trails in Post Canyon but leaves his enduring legacy in a 30-year career as a ranger in the Hood River/Barlow ranger district—and over 150 miles of hand-built trail throughout the 44 Trails system.

Thornton recounts the first time he proposed that Dog River, a well-worn horse trail, open for mountain bikers in the mid-90s.

“They didn’t believe bikes could climb that,” he says. But even after hearing “no” more times than he could count, Thornton persisted. “I was a nut,” he says. “I pushed it at Mount Hood National Forest recreation meetings again and again.”

National forest officials stood their ground, arguing that the trail crossed into a wilderness area just seven miles from the trailhead. But Thornton insisted that a strong mountain bike trail alternative didn’t need to approach the wilderness boundary line. Eventually, he prevailed.

While most riders now shuttle the 5.8 miles of brake-melting singletrack known as Dog River, it remains as novel today as when it was first sanctioned. And Thornton’s unrelenting drive to build additional mountain bike trails produced more local classics, such as the higher-elevation Gunsight Butte trail. These and several other signature Hood River trails offer a more traditional mountain bike experience; one that feels raw and untouched, closer to the earth yet high above the river valley below.

JIMMY THORNTON RECOUNTS THE FIRST TIME HE PROPOSED THAT DOG RIVER, A WELL-WORN HORSE TRAIL, OPEN FOR MOUNTAIN BIKERS IN THE MID-90S. “THEY DIDN’T BELIEVE BIKES COULD CLIMB THAT. I WAS A NUT. I PUSHED IT AT MOUNT HOOD NATIONAL FOREST RECREATION MEETINGS AGAIN AND AGAIN.”

Trails like these constitute a nice contrast with the big-hit, built-for-long-travel lines of Post Canyon’s past and present. Many people consider them a reminder that skinny singletrack is kinder to the earth and there’s true freedom in riding for hours without seeing another soul.

“Post Canyon is an amusement park,” Thornton says. “What they’re missing if they don’t experience riding like you can get up on Dog River, Gunsight Butte, or any of the other trails up in the 44, is the soul and spirit of adventure in the natural environment.”

Decades after Thornton unlocked Dog River to mountain bikers, HRATS gathered to face the monumental task of re-creating the beloved Post Canyon trail system. Then Klee died tragically after sustaining catastrophic injuries while riding the Whistler Mountain Bike Park.

“If there’s small solace to be had in this tragedy, it’s that Matt Klee died doing something he loved,” read the first line of a tribute in the local newspaper, the Columbia Gorge News.

Stirred by passion and the desire to realize a shared vision, the community united to build new trails such as Sister Wives, Kleeway and Float On—all trails Klee and fellow visionary Ben Ketler had proposed. Such unprecedented cooperation was an amazing feat from an historically splintered trailbuilding community.

“HOOD RIVER HAS A WEALTH OF RESOURCES: COMMUNITY MOUNTAIN BIKING EVENTS, WORLD CLASS COACHES, A TRAIL SYSTEM THAT NURTURES SAFE PROGRESSION, AND A CULTURE THAT IS INCREDIBLY SUPPORTIVE AND WELCOMING. WE’RE TAKING THAT FORMULA AND ACTIVELY WORKING TO REPLICATE IT ELSEWHERE.”—Melissa Shays

“It was blowing my mind,” Paasch says. “Those were the first machine-built trails in Post Canyon, and hundreds of people turned out to help.”

Post Canyon was not resurrected simply by the man-power that HRATS rallied, but rather by the collective desire to create a system that was safe and intuitive for riders of varying skill levels, from kids just learning to ride to seasoned freeriders, says Melissa Shays, a fixture of the local mountain bike community who is the mother of boys.

“I started working with the Junior Committee for the Oregon Bicycle Racing Association a few years after my oldest, Kai, started racing,” Shays says. “We’re actively working on figuring out ways to get more kids involved

and foster a sense of community in mountain biking pockets across Oregon. Hood River has a wealth of resources—community mountain biking events, world-class coaches, a trail system that nurtures safe progression, and a culture that is incredibly supportive and welcoming. We’re taking that formula and actively working to replicate it elsewhere.”

Kai, who will turn 15 this year, is quick to add, “I was there at the work party last year—the one with over 200 people on Mitchell Ridge. I had a ton of fun doing it and I remember not wanting to leave.”

Enjoy what you just read? Consider joining or donating to the advocacy groups and trail builders that make these areas possible.