Until the Bitter End Adventure, Romance and ‘90s Alt-Rock in New Zealand

Words by Brian Haffner

It’s an early April morning, and a touch of autumn is in the air as the two-liter, four-cylinder engine sputters to life.

The 1994 Ford Econovan, dubbed “Black Mamba,” pulls out of Christchurch, New Zealand, headed south along the coast toward the town of Dunedin. Like most vans in the country, the Mamba backfires as she makes her way down the two-lane highway, her rust-eaten chassis shaking with the potholes.

Inside are four smelly tourists, all on three-month visitor’s visas. Mark Taylor is at the wheel, talking Tinder and snacks, while Will Cadham gives him incorrect directions. Simon McLaine heckles both from a makeshift plywood bench in the back, while trying not to cough from a mix of exhaust fumes and dirty chamois odor.

I’m crammed in the middle, pointing my long-obsolete Super 8 camera out the Mamba’s equally abused windshield to capture, well, whatever we find ahead. Considering the past few weeks, that could include nearly anything.

This journey began at the end of January, when we left North America with intentions of racing in New Zealand for the 2017 winter season. To save money, the four of us decided to share expenses, buy a used van and make a documentary about privateer racing. But those plans began to unravel just a few days after arriving in Christchurch, when we learned there was a computer issue with the online lottery system. This meant if we wanted to compete in any of our scheduled races beyond the first two, we’d have to re-enter our names and hope we’d be selected by chance. We should have been anxious—those races were our reason for being in the country.

“Fuck it,” Mark joked. “I’m not going to re-enter.”

We laughed. But as that faded, we all exchanged quizzical looks. Were the others kidding? Or was there some concurrence deep within our ridicule?

When the lottery reopened, none of us entered. Suddenly, we found ourselves in New Zealand with months of free time, endless miles of unexplored trail, and a big van called the Black Mamba.

In February, we’d raced the two events for which we were still registered, but once that was done we’d officially completed our professional obligations. The courses also covered most of the South Island’s classic riding areas, and over the next two months we ticked off the trails in Queenstown, as well as both the Wakamarina and Whites Bay tracks. Between rides, we explored the north end of the island, wandering through the famed Wairoa Gorge, marveling at the New Zealand Alps, and driving along the lush west coast.

But the southern half of the island, particularly the east coast, remained untapped. We knew there was riding. We just didn’t know what kind, or the quality, so we formulated a plan. We’d return to Queenstown and its fantastic trails, but take the long way: south from Christchurch down the coast, then north through Fiordlands National Park. After arriving back in Queenstown, we’d make our way to Christchurch in time for our flights home.

Which brings us to our smelly April departure, and a coffee stand on the way out of Christchurch. The girl behind the counter asks us where we’re headed, and when we answer Dunedin she is instantly excited. We’d picked the town as our first destination after coming across a magazine in a grocery store with an image of an inviting series of pine-needle-covered turns.

“I love Dunedin,” she says. “But be careful if you party down there.”

“Be careful?”

“Oh yeah, Dunedin is wild, man,” she says. “It pops off in the streets. At the last party I went to down there, they tore the house apart. Just destroyed it. Ah, I’m so jealous you’re going to Dunedin.”

What did “popping off in the streets” mean, literally? We speed down the coastline at 40 mph, the top sustainable speed for the Black Mamba, eager to find answers to these questions.

Decidedly intrigued and slightly nervous, we head south. What kind of place was this, with loamy trails and an infamous party scene? Would there be girls? What did “popping off in the streets” mean, literally? We speed down the coastline at 40 mph, the top sustainable speed for the Black Mamba, eager to find answers to these questions.

Only a few minutes after arrival we see an example of “popping off.” Driving through downtown en route to the trails, we turn onto a side street and are stopped abruptly as a group of university students and middle-aged partiers cross the street between a grim-looking apartment building and a rundown house. Dressed in costumes ranging from giant rabbits to slutty robots and carrying beverages in both hands, they are struggling visibly to remain upright. It is about 10 a.m.

Later in the day, at the Rotorua EWS race we should have been attending, Kiwi underdogs Wyn Masters, Matt Walker and Ed Masters will masterfully battle through heavy rains, navigating a gauntlet of slick roots to take first, second and third. Somehow, they seem comfortable in the slippery morass, and within the first 50 feet of our ride in Dunedin, we quickly figure out why the race was won by locals.

Thanks to a healthy amount of rain over the past week, the pine needles that looked so appealing in the magazine have combined with the unique, clay-based soil to create an absence of traction, more comparable to ice than dirt. Even Mark and Will, who are used to surviving winter trail conditions in Vancouver, BC, ride most sections with both feet off the pedals and crotches on their top tubes. Back at the safety of the parking lot, one statement comes from our lips: “Thank God we weren’t racing.”

Though we search for better options, our campsite in Dunedin is as grim as the conditions. Camping in New Zealand is heavily regulated, mostly due to a rapidly growing, Instagram-fueled influx of van-living tourists. To prevent them from literally shitting all over the country, “freedom camping”—just parking in a random spot and sleeping in your vehicle—is limited to those with self-contained toilets and gray water tanks. Vehicles without these amenities can only camp legally in designated campgrounds.

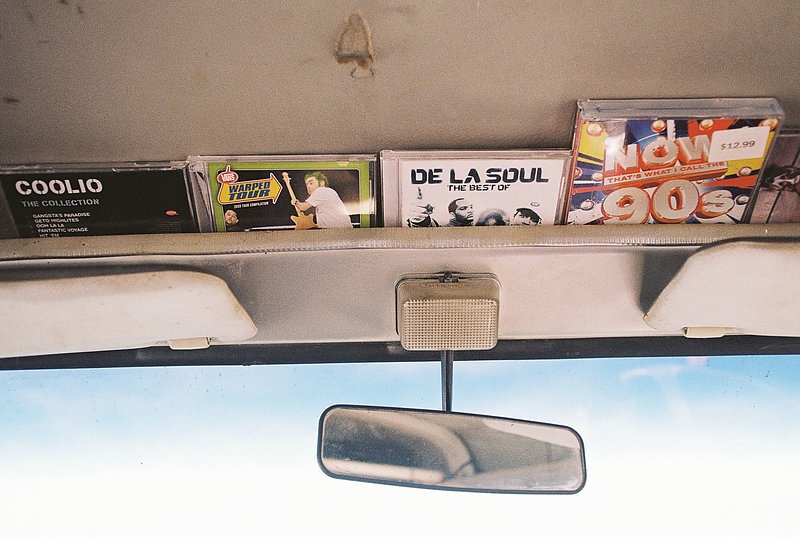

The Black Mamba falls squarely into the latter category, and so we cram into a grass field that closely resembles a music-festival parking lot. Two groups of campers battle for control over the zone’s soundtrack, one blaring groovy jams and the other ’90s alt-rock hits late into the night. As we struggle to fall asleep, we decide that whatever genre prevails, there can be no winners in this conflict.

As we comb Google Maps the next morning for a quieter campground, Simon receives a mysterious text from “Jake,” a friend of a friend in Bluff, a town a few hours south. The message offers tales of seldom-ridden trails, hidden descents and free camping. We are skeptical, but another night listening to the battle of the bands isn’t an option. Once again, we point the Mamba south.

Bluff is a small fishing town at the southernmost end of New Zealand. It is renowned for its oysters, which are considered a delicacy throughout the country, but its trails are obscure at best. We meet Jake the next morning at the local coffee shop, but immediately upon our arrival we’re distracted by the shop’s purveyor, a big, friendly Maori bloke who emerges from the kitchen with a large tub of oysters. Despite it being 8:30 a.m., he’s already snacking on the shellfish, and he offers us a sample before taking our coffee orders.

We reluctantly accept, because his tone implies that declining isn’t an option. It quickly becomes apparent that in Bluff, “sample size” means eating the whole tub.

Our stomachs churning from our unwanted breakfast, we follow Jake into the hills behind town and through a surprisingly extensive maze of trails. Jake is familiar with the area and its history, having spent 20 years here before moving north to a larger town (the lack of women in Bluff had something to do with this, he tells us). But during those two decades, he constructed a labyrinth of trails to rival anything else we’ve ridden on the island—tight and tech, with axle-deep pine loam in places, all accessed by a paved shuttle road. He returns every year, and it’s obvious why.

After getting our fill of oysters and Jake’s trails, we head north. However, the lack of maintenance the Black Mamba has endured during her 200,000-mile life is starting to become apparent. Since we purchased the van in early February, she has required an occasional push start—not unusual for a vehicle her age.

But as we drive the narrow road through Fiordlands toward the tourist destination of Milford Sound, it becomes a regular maneuver. We still see it as more of an inconvenience than a serious issue. Each time we push the van out of one of the park’s scenic overlooks, we can’t help but enjoy the shocked reactions of wealthy European families and busloads of Asian tourists.

It’s about this time that the Mamba starts dying while idling, making intersections exciting obstacles. Initially, Mark is able to bump start the van before lights turn green. But that becomes less common as we near Queenstown, meaning the rest of us must get out and push before jumping back into the van as the Mamba lurches through traffic.

The miles to our destination tick down, and we all utter silent prayers, cross our fingers, and hold our collective breath in hopes we’ll make it.

The miles to our destination tick down, and we all utter silent prayers, cross our fingers, and hold our collective breath in hopes we’ll make it. Tensions are high right until the moment we pull into our camp spot, and, after one last backfire, Mark turns off the engine—intentionally, this time.

Our relief increases as we check out the campground. It has numbered slots and enforced quiet hours, and is within riding distance of everything four responsible athletes need: the bike park, the grocery store, the liquor store and the ice cream shop. Compared to Dunedin, it’s paradise, so we decide to call this base camp until we return to Christchurch. And perhaps the rest will somehow resolve the Black Mamba’s issues, or at least extend its life by a few hours.

It’s a great, practical plan, with a high chance of success. But then we meet Steph.

Steph is a lovely Canadian girl visiting Wanaka on holiday, who Will met via the dating app Tinder. The two spent a few days chatting online, and Steph suggested Will come visit Wanaka. After three months surrounded by smelly dudes, we are all understandably hurting for female companionship, and Will can’t take it anymore. He tells us he’s taking the van to Wanaka. Since the rest of us are also living in the van, that means we’re going too.

Mechanical issues aside, by this point the Mamba has developed a very serious odor issue. In preparation for his date, Will wedges some wild sage into the ceiling, which he proceeds to burn for the entirety of the two-hour commute to Wanaka. It smells an awful lot like weed, but we assume our collective sense of smell has been so tainted by foot odor that it’s become completely unreliable. We choose to ignore it.

Will’s date goes well, enough so that we stick around Wanaka for a few days so he and Steph can go on a few more. Each evening after riding, we burn more sage as Will gets ready for the night’s date. And each morning, the weed smell becomes harder and harder to ignore, until one night the sage catches the ceiling on fire. The resulting fumes are incredibly potent, a mixture of quasi-weed and whatever odors the Black Mamba’s ceiling had absorbed from her previous owners.

It’s a testament to Steph’s character that, during their date later that night, she doesn’t comment on the fact that Will smells like a roadie for the Dave Matthews Band.

Alas, it’s a romance not meant to last, and Steph heads back to Canada as we once again point the Mamba toward Christchurch. Along the way is Craigieburn, a small town with impressive riding that we know is some of the best on the South Island. The descents are long, as are the gravel roads we must shuttle to access the trails. We’re all tired, but it’s too good to pass up, and Mark volunteers to drive for the first lap.

In a show of unexpected gumption, the Black Mamba makes the climb without any issues. The problems start on the way down, as Mark navigates the steep, winding shuttle road after dropping us off. At one point the engine’s RPMs drop too low, and the whole vehicle dies—including the power steering and power braking—just as it enters an exposed switchback. Somehow, Mark is able to manhandle the van around the turn, and frantically bump starts the engine moments before disaster. By the time he meets us at the bottom, he has decided the Mamba has made her last shuttle lap. We don’t argue.

Mark is fine, but the Mamba never recovers. Still, we’re able to limp our reggae-scented, barely running death trap back to Christchurch. She has served us loyally, facilitating our adventure until the bitter end, for which we pay our respects, drinking an honorary beer at the first gas station we reach in Christchurch.

After that, we sell her for $300 worth of scrap metal.

![“Brett Rheeder’s front flip off the start drop at Crankworx in 2019 was sure impressive but also a lead up to a first-ever windshield wiper in competition,” said photographer Paris Gore. “Although Emil [Johansson] took the win, Brett was on a roll of a year and took the overall FMB World Championship win. I just remember at the time some of these tricks were still so new to competition—it was mind-blowing to witness.” Photo: Paris Gore | 2019](https://freehub.com/sites/freehub/files/styles/grid_teaser/public/articles/Decades_in_the_Making_Opener.jpg)