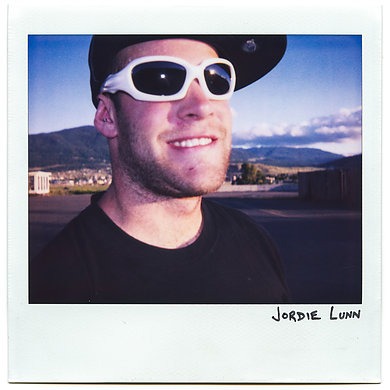

Jordie Lunn In Memoriam

Words by Brice Minnigh

Editor's Note: This article was originally written and published in 2019. The Freehub team is resurfacing this tribute to commemorate the anniversary of Jordie's passing.

Mountain biking has lost another one of its greatest ambassadors with last week’s tragic passing of Jordie Lunn.

The Canadian racer-turned-freerider's larger-than-life presence and perseverance has left an indelible imprint on our sport. Over the course of a 20-plus-year career that spanned multiple eras, Lunn’s impact was every bit as palpable as his momentous triumphs and gut-wrenching crashes.

At 36—an age when many freeriders gracefully graduate into more forgiving disciplines—Lunn was charging as hard as ever, inspiring countless riders around the world with fearless, mind-bending moves that most humans could scarcely imagine. Even in his last days, Lunn was doing what he loved most: Riding fast and free with close friends, keeping the stoke level high with his infectious exuberance. His untimely passing came after a crash while riding in Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, with Darren Berrecloth, Greg Watts and Brayden Barrett-Hay.

Though his riding alone was enough to sear his legacy into the minds of mountain bikers worldwide, it was his exceptional kindness and magnanimous spirit that truly set him apart. In an action-sports realm in which results are paramount, Lunn consistently placed relationships and basic human interaction above all else—including his own competitive interests. He literally had time for everyone, from fellow athletes to fans, from the youngest groms to their parents and grandparents. To Lunn, there was no such thing as a ‘random’: Everyone was important.

“He was such a loving human, and he showed that love to people from all walks of life,” says freeride veteran Cam McCaul, a longtime friend whose entire family was close to Lunn. “He made an impact on everyone he met, from a six-year-old kid to a 63-year-old woman. He could relate to everyone, and because of that everyone cared about him. From my daughters to my mom, everyone cared equally about him.”

At competitions, Lunn unfailingly placed the communal atmosphere ahead of his own performance, stopping to sign autographs, talk to fans and actually get to know people. Even in the face of death-defying Rampage lines and daunting Joyride jumps, he routinely chose friendly conversation over mental preparation.

“Jordie viewed it as his duty to keep the stoke alive and spread the love,” says childhood friend Berrecloth, whose bond with Lunn stretched from the early days of riding bikes in their hometown of Parksville, B.C., to his final moments in Mexico. “We grew up in a small town and remember those days when we would meet our childhood heroes, and how devastating it was if they didn’t give us the time of day. And Jordie wanted to make sure he never made any kid feel like that.”

Though Lunn’s vibrant personality was what most endeared him to fans, his riding accomplishments were extraordinary in their own right. In a professional career that spanned two decades, his achievements influenced multiple generations of riders across a broad spectrum. From his teenage success as a downhill racer to his unforgettable segments in numerous freeride films, his storied trajectory was filled with watershed moments. In a very real sense, Lunn’s freeride filmography bridges the entire history of freeride to date: Starting with his breakout role in the groundbreaking 2000 movie, Ride to the Hills, all the way to his recent, self-produced Rough AF video trilogy.

“In what we call freeride, in what’s actually shaped this niche of mountain biking, Jordie has been right there the whole time,” says veteran freerider Matt Hunter. “I actually can’t even imagine what the freeride world would look like without him.”

In Ride to the Hills, the young DH racer joined freeride pioneers Andrew Shandro and Dave Watson, as well as Jesse Roberts and Cody Swansborough, for a rowdy segment on the mesas around Virgin, Utah. That site ended up being the venue for the original Rampage contest.

“For that shoot, we rented two mobile homes and hit the desert, pulling over on some gravel roads when it got dark,” recalls photographer Sterling Lorence, who shot still images for the film. “When we woke up the next morning, we looked out the windows and were just freakin’ out over those mesas.

“Jordie was only 16, but he was already regarded as a powerful big-mountain rider, and he really wanted to ride those big lines with the boys,” Lorence adds. “He brought downhill skills into the freeride realm, and that was huge.”

It was during this Ride to the Hills shoot that the freeride world got its first taste of Jordie’s boundless energy and mischievous nature, says Anthill Films co-founder Darcy Wittenburg, who was there for his first bona fide film shoot.

“We were all crammed into these RVs, and Jordie was just being a full grom, making a lot of noise and farting the whole time,” laughs Wittenburg. “Shandro was a sort of chaperone for Jordie, and at a certain point he just kicked him out of the RV and Jordie ended up having to sleep all night on a picnic table.”

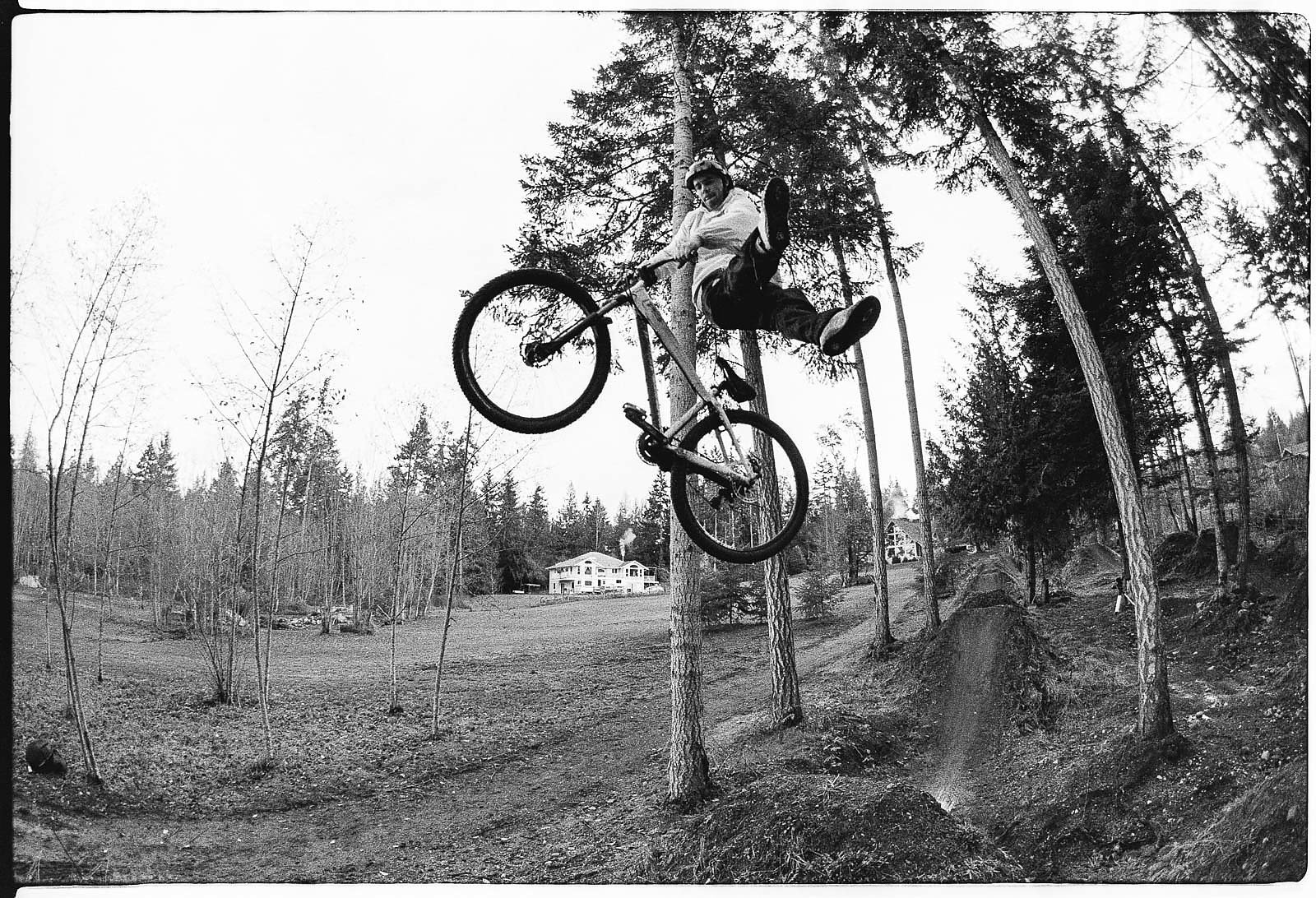

Lunn’s riding spoke for itself, and with an ever-positive attitude that made him a true asset on film shoots, his freeride career took off. Throughout the next six years, he landed major segments in films such as 2004’s The Collective and 2006’s ROAM, the latter of which featured unforgettable scenes of Ryder Kasprick, McCaul and Lunn hitting the dirt jumps in his own backyard. Though ROAM immortalized these backyard jumps among the general riding public, for Lunn’s ever-expanding circle of friends they were merely a place to meet and have fun on bikes.

Lunn’s parents, Bonnie and Brian, were faithful supporters of the riding endeavors of he and his two brothers, Craig and Jarrett. They were happy to let their friends dig jumps and clown around in this continually evolving dirt playground. Over time, it became a veritable community center for bike riders, and new people were always welcome.

“I’ll never forget the time I was going over to [Vancouver] Island, hoping to ride his jumps, and I stepped off the ferry to see Jordie had come to pick me up,” says Ross Measures, a former pro rider and longtime SRAM employee. “He drove 40 minutes to pick up a kid he didn’t know. Seeing him in Run to the Hills and The Collective, I just thought he was the coolest dude ever. And then I was suddenly friends with him.”

This is a story echoed in some form or fashion by countless riders who were welcomed into the Lunn family fold and immediately inducted into the Vancouver Island riding scene. Over the years, Lunn’s backyard jumps were the site of multiple home-grown contests with names like the Jordtron Jumpathon, the Peanut Butter Knife Fight and Fresh Air. And through it all, Lunn was the lynchpin—for both the riding and the never-ending, extra-curricular fun.

In the days since Lunn’s death, the groundswell of emotion and memories pumping through social media feeds has been overwhelming. Hundreds upon hundreds of friends and fans have posted personal photos of all manner of shenanigans, from drinking games to scantily clad costume parties—all backed up with painfully heartfelt words expressing how much Lunn meant to them.

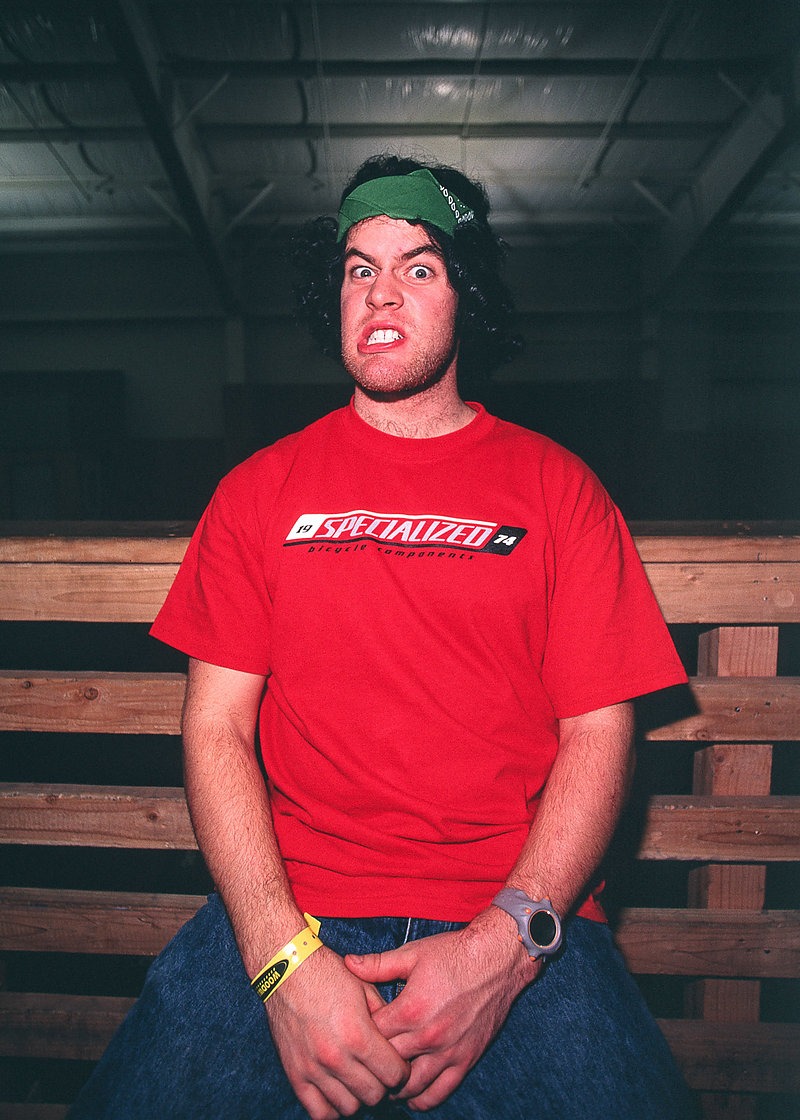

“He had this ability to find something fun and funny in any situation, and it was incredibly contagious,” McCaul says. “He could walk into any room, and even if the vibe was already positive, he would always put it up a couple of notches. Witnessing him elevate an entire group of people was amazing.”

This elevation of spirits extended everywhere he went. And, if there was riding and a party involved, Lunn could be counted on for support—even for contests in which he wasn’t competing. From Rampage to Crankworx to Fest Series events, Lunn would be there, ready to ride, pick up a shovel or crack open a beer and get the festivities going.

“His presence was commanding, and you never really knew what you were going to get. But you always knew that whatever it was, it was going to be good."—Ross Measures

“Jordie loved the riding community, and he was always around,” Measures says. “His presence was commanding, and you never really knew what you were going to get. But you always knew that whatever it was, it was going to be good. If I saw Jordie somewhere, I immediately knew I was in the right spot.”

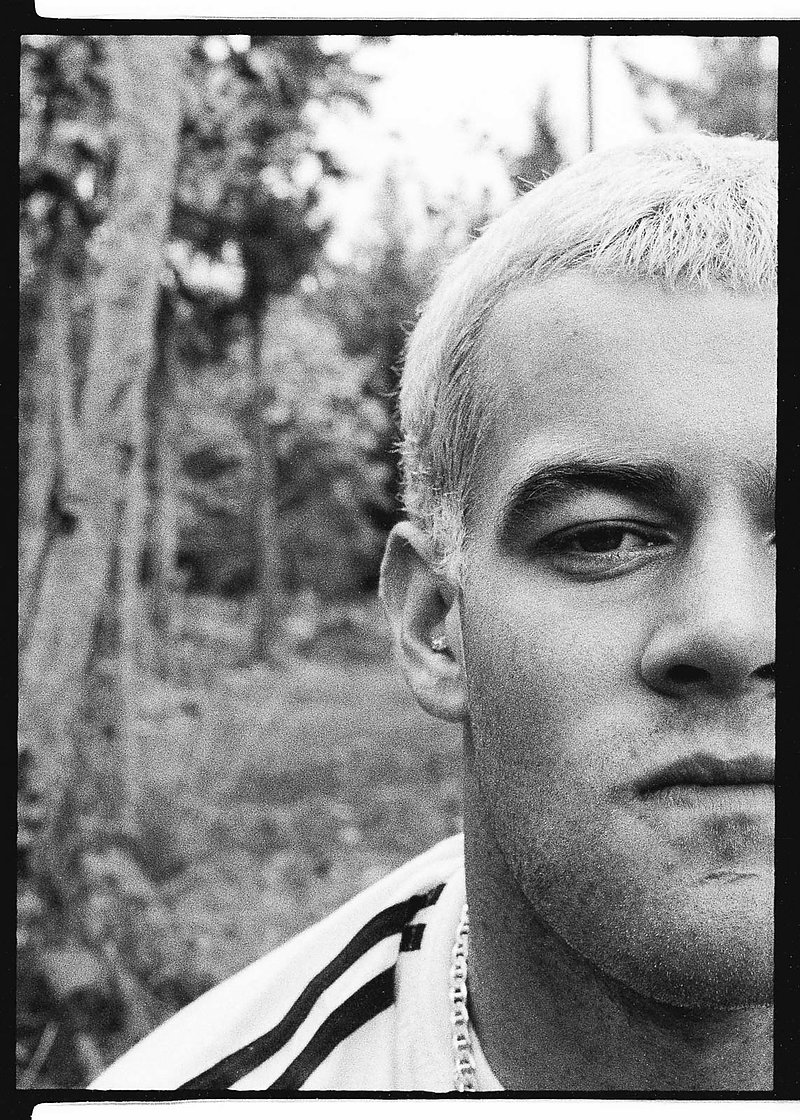

Lunn’s individuality was also expressed through his appearance. In his younger days, he was known for his outlandish riding kits and constantly changing hairstyles. Over the years, his steady accumulation of tattoos that eventually spread to his neck and head made him stand out in any crowd. Add to this his assortment of gold teeth and you had a sight that could make even the most hardened gangbanger shudder.

“Jordie put a lot of thought into his appearance, on and off the bike,” says freeride veteran Thomas Vanderham. “Whether it was wearing white pants on a muddy day, limited-edition Air Jordans in the bike park or just wearing pink on the golf course. It was fashion over function with Jordie, all the time. He really enjoyed being an individual and being a little different than everyone else.”

Underneath his increasingly brash appearance, however, lied a tenderness that could be tapped by anyone who approached him.

“His tattoos and gold teeth were almost the only way he could hide how big his heart was,” Lorence says. “Those were only skin deep, but once you get underneath them, he was just a big softie, a big teddy bear.”

Hunter fondly recalls the opening days of summer coaching camps at Silver Star, where he, Vanderham, Graham Agassiz, Matty Miles, Kenny Smith and Lunn would spend their days showing kids how to improve their skills.

“On the first day of camp, some of the parents would be a bit taken aback by Jordie’s appearance, but once they had a chance to talk to him, they’d always be so stoked,” Hunter says. “The kids were always coming back with stories about how cool he was, and by the end of the camp he’d be everyone’s best friend.”

By all accounts, Lunn loved kids, and he spent thousands of hours with them, coaching everything from the Elevate clinics at Silver Star to Summer Gravity Camps at the Whistler Mountain Bike Park and even hosting his own hometown clinics. It was a tangible way for him to share something he truly loved, and he was abundantly generous with his time.

“There was never a kid Jordie didn’t have time for,” Berrecloth says. “Sharing his knowledge and everything he’d learned over the years with the next generations was super important to him.”

Throughout his career, Lunn’s selflessness routinely led him to put the interests of others above his own, and he was more interested in spending time with friends and family than pushing for self-advancement and sponsorships. But the riding itself was a constant, and at its finest, it was downright revolutionary—like the time, at the 2007 Bearclaw Invitational, when he became the first human ever to pull a corked 720 on a bicycle.

“He’d already been a Canadian originator on the DH scene, but when he pulled that corked seven it notched him in the history books as being a slopestyle originator, and that set him on a really good path,” Berrecloth says. “After that there was some serious spark in his step for freeride.”

Though Lunn’s career and competition results ebbed and flowed over the years, he continued to send it on some of the biggest lines. And with the advent of the Fest Series, he found a perfect fit for his unrivaled ability to pump up the party train. During the Hoff Fest at Retallack Lodge in 2016, he gave a Who’s Who of the world’s most progressive big-mountain riders a show they’ll never forget.

“We’d all been riding the big jumps there from sun-up to sundown, just sessioning 60-foot jumps non-stop,” Vanderham remembers. “The sun was going down and everyone started winding down and having a beer. But Jordie was on fire, and he didn’t want to stop. He just kept riding and riding, until it was getting dark and kind of sketchy. We all gathered on the top of one jump and he just did this massive air over us and threw us the horns. We just went insane.”

It was around this time that Lunn staged a comeback that is arguably unparalleled in freeride history. Already in his early 30s—a time when many freeriders start to soften the hard edges of their careers—Lunn recaptured his focus, embarking on a furious fitness campaign and reinventing himself with a relentless DIY ethic. He began building trails, jumps and wooden features in the forest near his home, spending day after day in the woods with his dog constructing some of the scariest stunts in the history of freeride.

These jumps and wooden features were the backbone of Lunn’s singular vision for his Rough AF video series—a trilogy that sent shockwaves through the internet and turned online forums into modern-day coliseums. With his steely determination and some help from his friends, Lunn revived the raw essence of freeride, harking back to its rough-and-tumble roots.

“I’ll never forget it,” says close friend Rupert Walker, filmmaker and co-founder of Revel Co. “When Jordie was making his Rough AF videos, he literally spent every single day, from dawn to dusk, in that forest, building that insane shit with his bare hands. All that work is what really re-fired his career. The gaps, the ladder bridges, and that insane vertical tree ladder—that was some of the craziest shit ever. He built stunts that no one else would ride—not even the best riders in the world—but it didn’t matter because he knew how to ride it all.”

Those features, particularly the vertical tree ladder, were haunting echoes of freeriding’s early days on Vancouver’s North Shore, only amplified by Lunn’s uniquely artistic approach.

“Those stunts were Jordie’s expressions of his true self. When he took the bull by the horns and started building these, it was clear to all of us that he was pursuing his purpose.”—Darren Berrecloth

“Those stunts were Jordie’s expressions of his true self,” Berrecloth says. “And the words ‘rough as fuck’ were perfect. When he took the bull by the horns and started building these, it was clear to all of us that he was pursuing his purpose.”

When it comes to the now-infamous tree ladder, in one heart-stopping instant, Lunn hurtled his way into freeride greatness, instantly encapsulating the genre’s gritty soul and enshrining an icon that will come to personify its purest lifeblood.

“That tree ladder was the deadliest thing I’ve ever seen,” says Margus Riga, the photographer who captured the moment. “It was, by far, the scariest thing I’ve ever shot. He was standing at the top, looking down, and then he just freefell at least 40 feet into a 20-foot tranny. It was the roughest thing I’ve ever seen on a bike. We all just exploded and rushed up to him, and he was so happy. But what was really special was that it wasn’t about him doing it. It was about proving what is possible for a human to actually accomplish.”

On top of this, the Rough AF videos proved to the world that Lunn was back, and in 2018 he was invited back to Rampage at age 35.

“That’s pretty much unheard of,” says Vanderham, himself a veteran of multiple Rampages. “Once a rider moves on from that event, they’re generally not going to go back. You have to be in such a focused headspace to compete at Rampage. But I think Jordie felt like he had some unfinished business there and just really wanted to settle it.”

Simply returning to Utah’s towering mesas to compete just miles from where he filmed his first major film segment was a dream come true—not just for Lunn, but for all the riders and fans who’d grown to love everything he represented.

“His career is truly remarkable,” says photographer Haruki Noguchi, whose friendship with Lunn started in the early days of the backyard jump jams. “He genuinely enjoyed pushing the sport, and he would do whatever it took to push the bar. He never slowed down, and he pushed it all the way to the end. And to end your life doing what you truly love is nothing short of incredible.”

A donation page has been created to help Lunn's family cover the remaining medical expenses. Any help is greatly appreciated and all excess funds will go toward Lunn's passions in his name. This includes, but is not limited to, youth coaching programs, mountain bike facilities and concussion research.

![“Brett Rheeder’s front flip off the start drop at Crankworx in 2019 was sure impressive but also a lead up to a first-ever windshield wiper in competition,” said photographer Paris Gore. “Although Emil [Johansson] took the win, Brett was on a roll of a year and took the overall FMB World Championship win. I just remember at the time some of these tricks were still so new to competition—it was mind-blowing to witness.” Photo: Paris Gore | 2019](https://freehub.com/sites/freehub/files/styles/grid_teaser/public/articles/Decades_in_the_Making_Opener.jpg)