Just That Beautiful The Stories Behind Three Whistler Masterpieces

Words by Jann Eberharter

Trailbuilding is art.

Maybe not in the traditional sense, but even the greats like Michelangelo, Vincent van Gogh or Pablo Picasso would not deny that—like any other form of art—it’s creative interpretation. To mountain bikers, these ribbons of dirt are some of the most beautiful things on this planet.

Trails can’t be hung on a wall, but they can cover an entire valley and the peaks above. No place is this more evident than Whistler, BC, which for trail-junkies has become the Louvre, the Sistine Chapel and the Museum of Modern Art all wrapped into one. From the alpine epics on Mount Sproatt, to the renowned classics in the woods of Blackcomb, to both the perfectly manicured and wonderfully raw descents of the Whistler Mountain Bike Park, the array of ridable artwork in Whistler is unprecedented.

Despite this variety, one commonality runs through them all. Every inch was designed and sculpted by a talented trailbuilder, each with their own vision, operating on their own terms, for their own reasons. Most are mountain bikers, though a few will admit they build more than they ride, choosing to spend their free time perfecting their masterpieces.

Any day in the woods is a day well spent, and out of the many hours that go into building a trail there is no shortage of triumphs and tribulations. Every turn has a goal and every feature a purpose, giving each trail a unique story, not just of its creation but its intention as well.

This is the tale of three Whistler classics, told by the masters who created them.

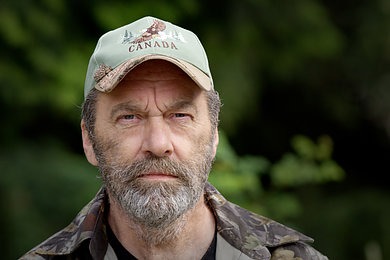

Dan Swanstrom // River Runs Through It

Dan Swanstrom first experienced Whistler in the winter of 1978, and by 1980 the Yukon-native was living in Whistler full-time as a ski bum. He originally came for the snow, but—like so many others—stayed for the dirt.

“I dirt-biked growing up, but mountain biking was pretty freeform,” he says. “It’s not like dragging a motor around and running out of gas. The only thing that runs out of gas is you.”

It was the early days of the sport in the valley, and it didn’t take Swanstrom long to tick off all the existing trails—one day, more specifically. Wanting more riding options, Swanstrom began creating them himself.

“I just became obsessed with trailbuilding,” he says. “I’d build the trail without cutting in the beginning or end, then the last day I’d go open them up, come back around, rip through it, and be stoked. Then I wouldn’t ride it again for years.”

By the mid-‘90s, Swanstrom’s trails occupied an epic gallery of Whistler masterworks, including Danimals, Ride Don’t Slide, and Rainbow’s End. In 1995, he built River Runs Through It, a meandering track through the forest near Alta Lake. As the name suggests, the trail can be slightly swampy and thus has plenty of North Shore-style woodwork to accommodate.

“The third day I was building the trail, I heard this rustling and weird sound,” Swanstrom says. “I realized a tree had fallen over and blocked Rainbow Creek, and all the water was coming through the forest. In a few minutes, I was knee deep. I just fell a big cottonwood over the river and rode across it—there we go, we had a bridge. After 15 years, that log was finally packing it in, so the Municipality put some money into it and built a decent bridge.”

The expenditure wasn’t surprising; when the Municipality put a counter on the trail to measure traffic, it clocked 13,400 riders in three months. Swanstrom’s reaction? “That’s ridiculous.”

In recent years, the Municipality has revamped parts of the trail. There’s now a section with wooden berms, a drop and some ladder features. All are fun, but a notable departure from the style of the original. Different people want to ride different things, and in the end the Municipality was simply trying to create something for everyone.

Luckily, there are plenty of other places for Swanstrom to enact his artistic visions. The 65-year-old is still building trail, continuing his legacy as one of Whistler’s most prolific builders.

“Lots of people ask, ‘Why do you build trail?’” he says. “My answer? I just love doing it.”

Tom Prochazka // Dirt Merchant

In the late 1990s, an experiment was underway at a ski resort in British Columbia. To fill the slow summer months, Whistler began building a few lift-accessed mountain bike trails on the hill’s fallow slopes, and by the year 2000 the project was seeing promising—if modest—success. It was enough that Whistler’s management tentatively provided a tiny trailbuilding crew with some monstrous resources: an excavator, and a chunk of woods in which to use it.

Shortly after, in 2001, Tom Prochazka was appointed bike park manager, with the goal of creating something to bring mountain biking to the masses (and vice versa)—a tough proposition, considering insane difficulty was the golden attribute in trailbuilding at the time. The excavator offered a then-novel compromise: a wide, flowy trail that could be ridden by novices, sprinkled with jumps to tantalize advanced riders as well. The result was A-Line, and it would revolutionize the sport. But before the build crew was even finished, they had loftier visions. Literally.

“We wanted to go bigger than A-Line,” Prochazka says.

Dave Kelly, a fellow bike park employee, soon drew up plans for two future trails. One was Easy Does It, a beginner flow trail and first priority. The other was their “bigger” jump line: Dirt Merchant, which was put on hold until the park had completed a few user-friendly trails first. But thanks to a wrong turn, the crew’s dream trail came to fruition sooner than expected.

“As the guys were building Easy Does It, they got lost and went kind of steep,” Prochazka says. “So we decided we’d just build Dirt Merchant.”

Prochazka was able to green-light the trail with management, and the crew set to work. Considering the size of the planned features, their most difficult task was to ensure the gargantuan jumps were as practical and safe as they were fun. To do so, they tested each individually.

“The trail crew were shredders, so we’d build a jump and they’d hit it first to see how it was,” Prochazka says. “When you build a jump trail, if you get it spot on the first time, you’re doing really good. But you always find that a jump could be better, maybe longer or steeper, so the next time you get a machine in there, that’s what you do.”

In 2007, Prochazka left his job at the bike park to join Kelly in starting Gravity Logic, a trail consulting company. A bold move, based around a simple question: How big can the sport get if there’s only one bike park?

The answer, it turned out, was bigger than they ever imagined. In the decade-plus since Kelly and Prochazka started the company, Gravity Logic has built bike parks all over the world, from Vermont to Sweden to Guatemala. With each project comes new challenges and new opportunities.

“It’s kind of like art,” Prochazka says. “Each trail is different, and that’s the trailbuilder’s perception of how it should be. I’ve designed and built probably 1,000 km of trail, and it’s interesting to see the progression of our building and how we see things.”

Throughout it all, Gravity Logic and Whistler have maintained their relationship. And as Prochaska and Kelly’s first collaboration. Dirt Merchant remains the standard against which everything else is measured. It’s just that beautiful.

“Europeans are always asking me, ‘When are you going to build us a Dirt Merchant?’” says Prochazka, “and I tell them, ‘I won’t. There’s only one. I can build you a jump trail, but not Dirt Merchant.’”

Dan Raymond // Rockwork Orange

A Rockwork Orange was the first trail Dan Raymond ever built, and it started by accident. On a ride in 2009, Raymond noticed what looked like a new path headed off into the woods, but upon further inspection he found it dead-ended shortly after.

He put it out of his mind until a year later, when he once again passed the same entrance and found it unchanged. This time, Raymond began scouting features the area, and in 2010 he began linking them into a coherent trail—and quickly realized there was little dirt to work with. Rather than give up, he used what he did have: rock, and plenty of it. It’s a slow medium, and that pace allowed him to shape every feature to perfection.

“You only have one chance to make a beautiful line through the forest,” Raymond says. “I thought it would take an afternoon, but that turned into two years.”

More than a half decade later, Raymond is WORCA’s lead builder. His building style, however, is still influenced by his previous career as a professional snowboarder. It’s not a surprise, considering the same year Raymond started A Rockwork Orange, he also competed in the 2010 Vancouver Olympics. The way he uses terrain feels a lot like ripping powder on a snowboard, and just as he rarely snowboards in a straight line, he rarely builds in a straight line either.

“I like to think of each move as related to the next,” Raymond says. “Two moves that on their own could be very awkward, but in succession keeps you engaged. To me there is a sense of accomplishment making it through these difficult moves, and difficulty doesn’t mean it has to be huge or fast. Difficulty can be that balance of riding slowly around an obstacle. That’s part of the experience.”

As for the trail’s name? That was partly inspired by the surplus of stone, but anyone who has ridden the trail will realize the moniker—and Raymond’s building strategy—have more nefarious undertones.

“Clockwork Orange is a demented movie,” he says, “and as I discovered the terrain I thought, ‘Well, here’s terrain that’s just screaming for demented moves.’”

Perhaps the most twisted feature on the trail is a steep rock roll corner through two trees. It’s a treacherous, tricky move, which is exactly what Raymond intended; an unknown rider, however, apparently didn’t approve, and took the liberty of removing the trees. In the world of trailbuilding, that is a serious taboo.

“That was the hardest move of the trail,” Raymond says. “Not everyone sees a trail the same way. To me, going and changing somebody else’s trail, somebody else’s interpretation of that forest—that’s difficult to accept.”

It wasn’t one distinct moment that made Stanley Kubrick’s film so wonderfully haunting, and though Rockwork Orange’s most difficult feature has been dumbed down, the rest of the trail remains a prime example of Raymond’s building style: connecting unique, individual features in a way that creates one truly demented—and incredibly fun—bike ride.

“To me, a berm is a feature, but three berms in a row, they kind of all have a similar feel,” he says. “Whereas a certain rock face, connected to another rock face, connected to this gap between the trees…those features are what I like about biking.”

To learn more about biking in Whistler, visit whistler.com/bike

![“Brett Rheeder’s front flip off the start drop at Crankworx in 2019 was sure impressive but also a lead up to a first-ever windshield wiper in competition,” said photographer Paris Gore. “Although Emil [Johansson] took the win, Brett was on a roll of a year and took the overall FMB World Championship win. I just remember at the time some of these tricks were still so new to competition—it was mind-blowing to witness.” Photo: Paris Gore | 2019](https://freehub.com/sites/freehub/files/styles/grid_teaser/public/articles/Decades_in_the_Making_Opener.jpg)