Remote Learning Drawing from the Toiyabe Crest's Sage Wisdom

Words by Kurt Gensheimer | Photos by Ken Etzel

A short, stocky Latino man flashed a smile at me from under his wide-brimmed hat, moving his hands back and forth along a narrow ribbon of dirt that had previously been hidden by a thick wall of sagebrush. I’d watched him approaching from a mile away, free hiking across a massive slope with a flock of sheep following, tailed by his trusty sheep dog.

“¡Aaah … camino!” he exclaimed as he strode along the newly liberated path.

“¡Si!” was all I could muster in response, beaming widely, proud of myself for knowing what the man said. It was the first word I had uttered to another human in four days, because he was the first human I’d seen in four days. I stepped to the side of the trail and waved him through a freshly cut path up to the top of the ridge, where his giant white tent was pitched at an elevation of about 10,000 feet above sea level.

“¡Gracias!” he said, vanishing back into the sage with his flock close behind.

I’m not sure what the sheepherder thought of me, a lone, sweaty gringo covered in dirt, holding a cordless reciprocating saw, mowing down sagebrush like it was my life’s mission. It occurred to me that, in a real sense, this has been a life mission for me—at least ever since I first rode the Toiyabe Crest Trail (TCT) in 2016.

This magnificent, 72-mile trail runs north to south through Nevada’s Toiyabe Range, located in the center of the state, about 30 miles south of the half-horse town of Austin. A historic National Recreation Trail, the TCT’s southern half lies within the Arc Dome Wilderness, while the northern half lies outside the Wilderness area. I first learned of the trail after reading an article written in 2011 by my friend Yuri Hauswald about his unplanned overnighter on the TCT with two friends.

The crew had gotten a late start, and they had little information about the trail. It was so overgrown that they got lost numerous times, eventually running out of daylight and being forced to sleep rough on the edge of a cliff at an elevation of 9,000 feet above sea level. Thankfully the weather was favorable and they were able to shiver their way through the night with nothing more than an emergency blanket and a few granola bars, making it out safely the next day.

That story stuck with me, and in 2016 I convinced the original crew to make a second attempt at a single-day crossing, this time with me. Despite a daybreak start, we still ended up in the dark after 35 miles. But we didn’t get lost, as we’d come prepared with ample food and strong lights that allowed us to find our way to the trail’s northern terminus at the tiny outpost of Kingston. It remains one of the greatest days I’ve ever had on a mountain bike; not because it was the most ripping trail, but because it was high adventure in a truly remote region only a three-hour drive from my home in Reno.

After that life-altering experience, I dreamed constantly about how remarkable the ride would be if the trail were properly maintained. The trail’s 35-mile, non-Wilderness portion—which has 6,500 feet of climbing—was so choked with overgrown sage, mountain mahogany, wild rose, evergreens and aspens that it was incredibly slow going. There were multiple sections where the trail simply disappeared, requiring some tricky route-finding. I believed if this trail could be cleared it would be one of North America’s most unforgettable single-day epics.

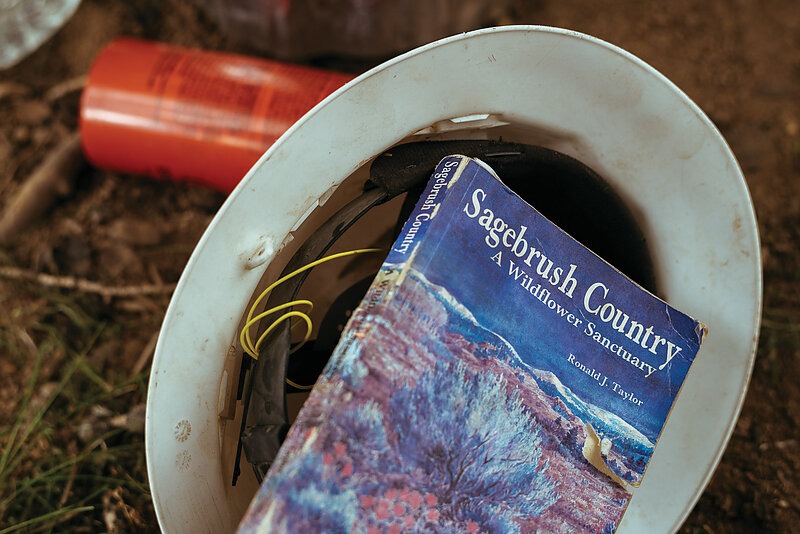

The next summer I got to work, spending weeks sawing through an endless sea of sagebrush with a couple of friends. In the Toiyabe, summer days are long and the sun is relentless, as there is precious little shade once out of the canyons. The saving grace is the trail’s high elevation, as temperatures rarely exceed the low 80s, even on the hottest of days. The work is tedious, wrestling one stringy floret of sagebrush after another out of the ground. The sage dust gets in your nostrils, causing constant bouts of sneezing and sometimes leading to nosebleeds. The stubborn, unbending brush slaps at your arms and legs, leaving bloody scratches as souvenirs of your labor.

The first day of work can be psychologically punishing. Minutes seem like hours. Hours seem like days. The very thought of doing this work over a 35-mile stretch seems impossible. But no matter how slow you’re going, simply looking around at the Toiyabe’s sheer beauty puts everything into perspective. You take a sip of cold spring water to reset the mind and fall back into sage-busting mode. It doesn’t take too long to find a rhythm.

By the third day of clearing, one becomes a brush-busting machine, blasting through walls of green in a complete trance. Life is simple. Get up, get to work, get dirty and tired, sleep like a stone, and then get up the next day and do it all over again. Each day you make it a little further down the trail, seeing the fruits of your labor, and before long an entire day will pass in what seems like a couple of hours. What started as a fool’s errand eventually turns into a dozen miles of trail being cleared. The light at the end of the tunnel becomes visible. You feel tired and invigorated at the same time.

The Toiyabe Range is deceptively diverse. In the middle of a state that most people write off as barren desert, it is brimming with water and life. Nevada’s longest mountain range—which runs for 130 miles and boasts a 30-mile stretch of peaks exceeding 10,000 feet in elevation—towers over the Big Smoky Valley, one of North America’s largest aquifers and longest-running basins. With the Toiyabe Range to the west and the Toquima Range to the east, water drains into the Big Smoky Valley with no exit. This water seeps into the ground and can be tapped by shallow wells, which often only need to be drilled 10 feet deep to cause a gusher of life to spring from the earth.

In the mountains, wildflowers explode in a kaleidoscope of colors all summer long. Dozens of bird species sing their songs from stands of aspen that thrive alongside year-round creeks, home to a healthy population of native Lahontan cutthroat trout. Antelope, elk, mule deer, bighorn sheep and mountain lions roam the hillsides, and one could be forgiven for mistaking these verdant canyons for the high country of Idaho or Utah.

One thing the Toiyabe is not brimming with is people. I’ve spent days camping in this region without seeing a single human. Spending a week in these lush canyons is the ultimate retreat from people and cell service, and when one finally returns to society, it’s with a sense of calm, peace and wisdom. A regular dose of the Toiyabe is all the medication I need to stay sane in a culture of insanity. It’s a place where you can look deep inside yourself amid a dramatic landscape that puts into perspective how insignificant your problems really are.

The TCT was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Army Corps of Engineers in the late 1930s. Nevada’s longest continuous trail is a testament to human perseverance and ingenuity, especially considering the time in which it was built and the remote-ness of its location. Running in the shadows of peaks reaching as high as 11,500 feet above sea level, the TCT contours through dozens of drainages, routed perfectly to catch one year-round spring after another. Some 90 years since the original builders first broke ground, most of the trail is still intact, despite having undergone almost zero maintenance in the last 40 years.

As part of the United States’ National Recreation Trail (NRT) network—which consists of almost 1,300 federally-designated NRTs totaling a length of more than 29,000 miles—the TCT is a small fish in a big pond. The network was created with the idea of promoting multi-use recreation, from hiking and horseback riding to cycling and even motorized use. An NRT can be anything from a slice of singletrack to a converted railway trail or even a paved pathway, and funds for their restoration or maintenance are designated through the federal Recreational Trails Program (RTP). Since 1993, the RTP has allocated $1.38 billion in federal funds toward trails, with an additional $1.02 billion in matching funds being raised by non-profit groups.

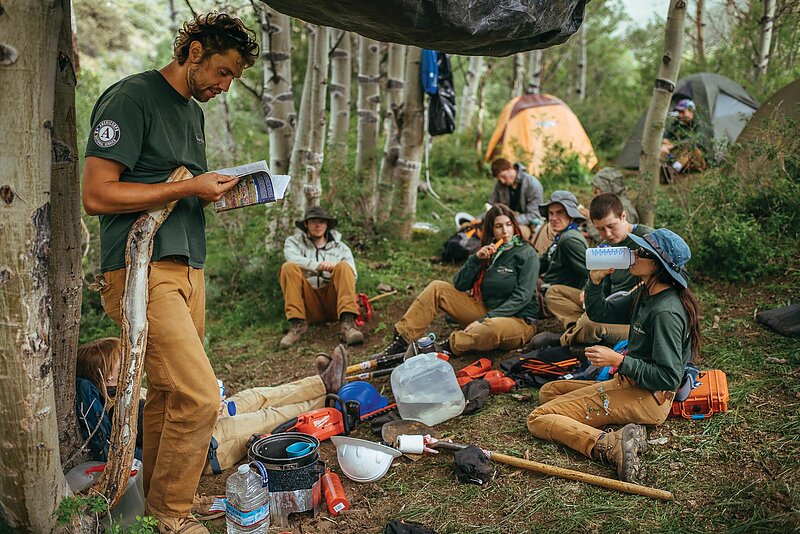

Few, if any, of those billions have been apportioned to the TCT. So, once my friends and I realized it would take a decade of our lives and a mountain of saw blades to clear the trail’s 35-mile non-Wilderness portion, we decided to apply for an RTP grant. With the help of The Great Basin Institute (GBI), a Reno-based conservation organization managing millions of dollars in federal grants, in 2019 we secured an RTP trail maintenance grant of almost $60,000 for the TCT’s resurrection. Though work was postponed in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this summer the GBI assembled a Nevada Conservation Corps (NCC) crew that completed several week-long deployments in the field—harkening back to the trail’s very beginning, when small teams of able-bodied CCC workers built the foundation that has lasted until today.

The work was exhausting, but the spirited NCC team members threw themselves into the sagebrush clearing and soaked up the serenity of their surroundings. The crew leader, Amos Frye—who has led trail projects from the Rocky Mountains to Alaska during his years with the conservation corps—was impressed by his first experience in the Toiyabe.

“The diversity of the landscape and wildlife, plus the scale of the terrain, make the Toiyabe very unique,” Frye said. “Then you factor in how remote this place is—there isn’t really anything else quite like the Toiyabe. Aside from the Sangre de Cristo Wilderness in Colorado, working in the Toiyabe is at the top of my favorite assignments ever.”

The Toiyabe is not for everyone, however. It is not a curated outdoor experience. It takes significant effort just to reach the trailhead. There is little trail information, scant signage and absolutely no services. The closest town, Austin, is 40 miles from the trailhead on a dirt road, and it has a population of fewer than 200 people. And the closest town to that is 100 miles in any direction. It is not a good place to get hurt.

“The feeling of remoteness is what really sticks with me,” said former professional racer Mark Weir, who experienced the TCT for the first time in 2018. “I’ve been to some remote parts of Africa, and the Toiyabe has the same feeling of utter solitude. You’re far away from anything or anyone. You’re in harm’s way, and if you screw up, there’s nobody around to help. But you don’t have to travel halfway around the world to some exotic place to get that feeling. It’s right in your backyard.”

Underscoring the TCT’s remoteness, the only other population center in the region is the tiny outpost of Kingston, located at the mouth of Kingston Canyon, four miles southeast of the TCT’s northern trailhead at Groves Lake. There are barely 100 year round residents of Kingston, and aside from the Lucky Spur Saloon—a must-stop watering hole—there isn’t much else going on in town. There used to be a bed and breakfast that recently became a private residence. The general store closed a few years back, as did the medical clinic. Even the saloon is for sale right now. Kingston’s future is uncertain, and most of the people in town aren’t even aware a national recreation trail starts just up the canyon from their houses.

Rekindling interest in the TCT could help bring a few businesses back to Kingston. Residents Chad and Candace Kelly are trying to start an adventure guiding company, Battleborn Adventures, that would lead moto rides and help mountain bikers access the TCT through shuttles. They also want to establish a small market to provide residents and visitors with simple food options—something that is sorely lacking, given that the closest place to buy groceries is 35 miles south in Round Mountain. There also is an acute shortage of lodging in town.

“Unlike a lot of other mountain towns, Kingston has almost no short-term rentals,” Chad said. “We want to get more people visiting the area, but if we can’t provide amenities like food and lodging, it severely limits Kingston’s ability to thrive as a destination.”

Once the TCT is restored to its former glory and word of its magic spreads, more visitors may come to Kingston and Austin. And if they do, it could open the door to the TCT’s next chapter: the construction of a new, 35-mile segment linking Kingston to Austin. This new section would be off-highway-vehicle legal for dirt-bike use, making the TCT the country’s only true hybrid national recreation trail featuring three distinctly different segments: Wilderness, non-motorized use and motorized access.

But before any new trail plans are approved, there’s still a lot of sagebrush to be cut. By the end of this summer, the TCT is expected to be clear from Kingston Canyon south about 20 miles to Tierney Canyon. At that point, it will be possible to ride from South San Juan Canyon to the TCT and then north for 12 miles before descending back to the start through Washington Canyon—a 25-mile loop with a hearty 4,000 feet of climbing.

Point-to-point shuttles are also an option, dropping riders at either Washington Canyon or South San Juan Canyon for challenging rides back to Kingston. Both routes feature a healthy amount of climbing, but the final descent to Groves Lake is what Weir calls a “gravity cavity”: a sliver of singletrack through an archway of tall sage with several steep straight-line sections. It’s a brake-burner descent, but the sight lines are excellent and other trail users can be seen from a distance.

The TCT’s non-Wilderness segment from Ophir Pass to Kingston Canyon is 35 miles, and fit individuals with solid route-finding skills should be able to complete it in a very long day. Half of this section is still overgrown, so a day-break start is required, as is carrying good maps and lights. For those wanting to experience this portion over two days, camping in South San Juan Canyon is a good halfway point. This route is expected to be fully cleared within two years, making it much easier to navigate.

There are hopes that the TCT’s ultimate restoration will serve as a paradigm for hundreds of other national recreation trails that have been all but forgotten. With more people riding mountain bikes than ever before, identifying historic trails and resurrecting them could be an ideal way to help diffuse increased traffic on well-known trails. Getting new users involved and securing grant funding through the Recreational Trails Program is a great place to start and adopting a worthy trail and restoring it might just change your life. It certainly has changed mine.