Let's Give it Hell Slightly Buzzed and Totally Blind at Trans-Cascadia

Words by Jann Eberharter

Volcanos are insane. As in, incomprehensible—for me at least.

The amount of sheer energy that lies dormant below is something I’ve only witnessed in sci-fi movies or imagined accompanying the apocalypse. But they’re also insanely beautiful.

From where I’m standing on Strawberry Mountain, I can see four volcanos and the view is slightly overwhelming. Mount Rainier is to the north, Mt. Adams toward the east, Oregon’s Mt. Hood visible to the south, and dominating the horizon to the southwest is St. Helens—or rather its leftovers. The top 1,300 feet blew off in 1980. The views from southern Washington’s Gifford Pinchot National Forest certainly don’t suck.

But I’m not here to stare at mountains, although it’s an enticing way to spend the day. Instead, I’ve got loppers in one hand and a gas can in the other. Neglected trails don’t care too much for the view, and they’re not going to clear themselves.

This mid-July weekend is one of three build parties hosted for (and by) the upcoming Trans-Cascadia. The event is a four-day backcountry enduro mountain bike race, but the ethos, operations and vision go far beyond racing. Along with putting on an epic party, organizers spend months beforehand opening and maintaining trails, quite often ones that haven’t seen footprints or tire tracks for decades. Then they send 100 people down each trail at race speeds, with the racers having zero knowledge of what’s around each corner.

Preparing old trail often means resurrecting it, and usually much more trail is scouted and cleared than what actually ends up included in the race. This is the least of their worries. Yes, it might mean extra effort and time, but those are things they’re happy to contribute. As a nonprofit organization, Trans-Cascadia has never cared too much about, well, profits. Organizers and volunteers alike are happy to be in the wild exploring new terrain, figuring out what’s possible and creating an unforgettable experience for those who show up to race.

The founders of Trans-Cascadia have discovered—or maybe more accurately created—a way to progress backcountry racing, while also giving back to the trails and communities that host the event. Four years into their endeavor, the work they’ve done and the relationships they’ve built are laying the foundation for more mountain biking in the Northwest’s volcanic paradise. And that deserves a party.

I first met Trans-Cascadia founders Alex Gardner, Nick Gibson and Tommy Magrath at Green River Horse Camp, 11 miles northeast of Mt. St. Helens and two hours from the nearest town, during the second of three weekend work parties. Cell service is nonexistent in most places Trans-Cascadia operates, and that’s the way they like it. Anywhere from 20 to 50 people will show up during a given build weekend, a mix of industry supporters, race volunteers and local enthusiasts.

Mornings kick off sometime around 7 a.m. (if not earlier) and although everyone treats their coffee like an IV, they’re ready for work. Groups are sent in different directions, prepared to do brushwork, saw trees or dig bench cuts where needed. By this stage in the reconnaissance, the Trans-Cascadia crew usually knows what trails are in the vicinity, but the current state of them is what’s in question.

The madness is directed by Alex, Nick and Tommy, who have been friends for more than a decade. The three have long been part of the bike industry as reps, working for Modus Sport Group, a sales agency out of Bend, OR, and working closely with high-profile brands. While living throughout the Northwest they spent countless weekends exploring the expansive forests of Cascadia, becoming mesmerized by the terrain.

Their collective experience was the perfect storm for creating a one-of-a-kind event: They had solid relationships within the bike industry, a love of showing off the Northwest and experience racing. Combining those things, they realized, would deliver exactly what they loved most: riding new trails at high speeds with good friends. And like most grand schemes, it gained life through a few beers.

“Nick, Alex and I were at a reggae bar in Laguna [CA] called the Dirty Bird, and we started talking about putting on this race in the Northwest,” says Tommy, who’s head of logistics. “I exited about halfway through the night, because I thought they were crazy. The next morning we were still talking about it.”

Nick had raced a fair amount, but his preferred style was far beyond a simple stage race. He’d competed in Megavalanche, a race in the French Alps that kicks off with a mass-start of 250 people on a snowfield, and Trans-Provence, a six-day, blind enduro race through the alps, both of which are known for being demanding and exhilarating.

Influenced largely by the Trans-Provence, Nick knew his home region had the terrain to host an epic backcountry stage race and that the blind format would align ridiculously well with the trails of the Cascades. With friends as driven as Alex and Tommy, all they needed was someone crazy enough to fund their grand plan.

“Casual conversations turned into big ideas,” Alex Gardner, event producer, says. “I coerced [Nick and Tommy] into thinking it was possible, and we asked Shimano for sponsorship and told them how great this idea would be. They bought on and funded us out of the gate.”

That was 2014, and once finally back home after a long summer spent traveling for Modus, the trio scouted a few areas within the Willamette National Forest they knew had trails up to par, trying to visualize stages, camp logistics and simply what a backcountry race might mean in this area. The trails they rode we so good they had to give it a go.

“You only get to experience trails for the first time once. So when somebody is willing to curate a ride for you and take you on this journey that they’ve envisioned or spent years developing, it’s a pretty special experience.”

—Nick Gibson

“You only get to experience trails for the first time once,” says Nick, who now serves as Trans-Cascadia’s race director. “So when somebody is willing to curate a ride for you and take you on this journey that they’ve envisioned or spent years developing, it’s a pretty special experience.”

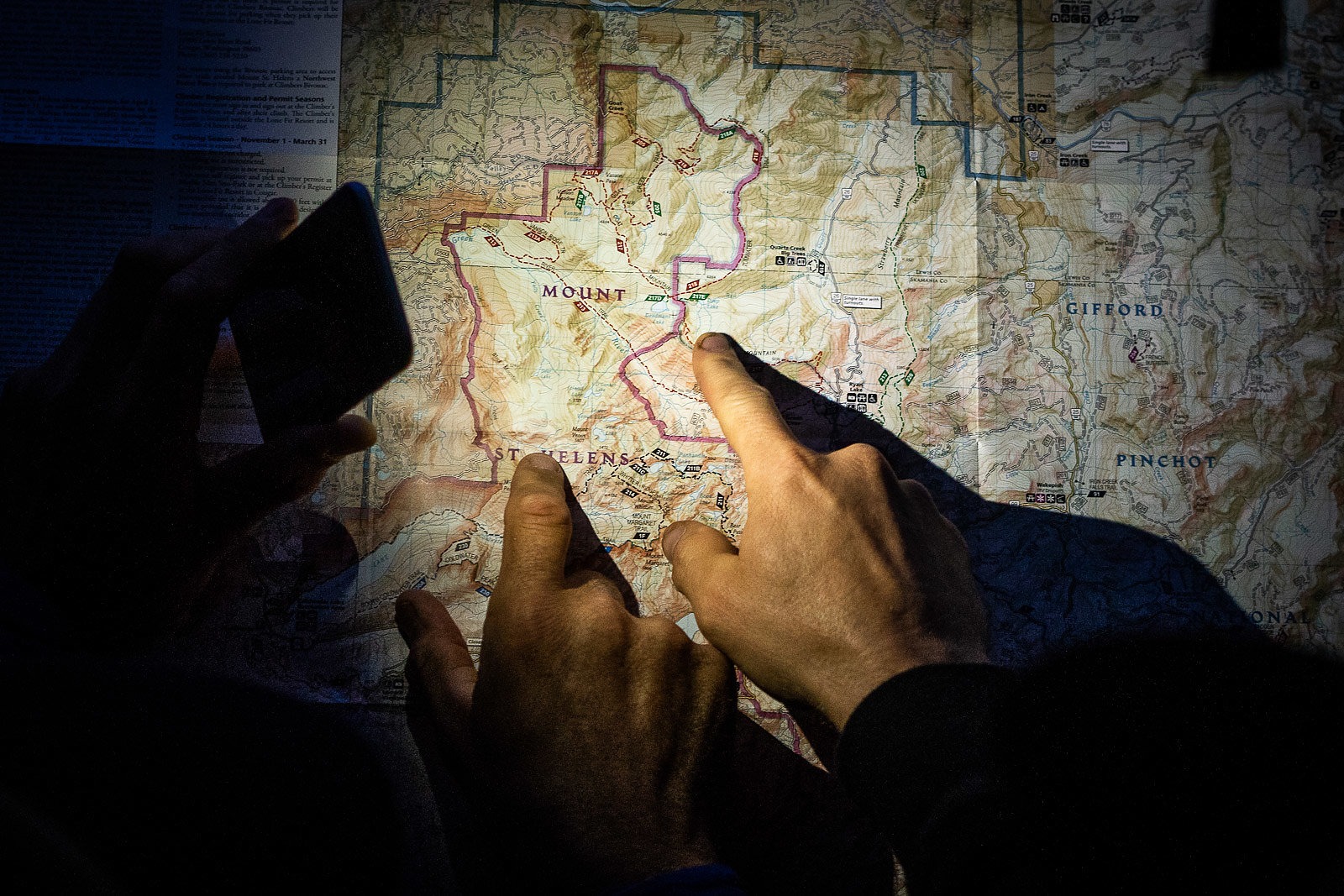

With devising such a journey in mind, they started poring over maps, talking to ranger districts and scouting central Oregon on dirt bikes.

“Once we got out to Lake Timpanogas, it was epically beautiful and the trails were super fun,” Tommy says. “From there, you could tell it was going to be a good thing; it didn’t matter how many people signed up that first year or really how it went, even the worst scenario was going to be an amazing weekend. That was when it was like, this is going to be fun, let’s give it hell.”

And give it hell they did. The next fall, the inaugural Trans-Cascadia officially kicked off outside of Oakridge, OR. Sixty-six racers showed up, and the days that ensued exceeded the expectations of everyone involved—Nick, Alex and Tommy included. Not only had they pulled off one of the most ambitious parties of all time, but they’d also proved their hunch correct: Cascadia had the potential to host a damn good race.

The terrain held so much opportunity that they returned in 2016 and 2017, giving themselves a leg up on logistics, and allowing them to open more trail in the area. By its fourth year, Trans-Cascadia had attracted some impressive names to its roster, including legends like Kathy Pruitt, Bryn Atkinson, Mark Weir and Geoff Kabush. Each year, the much-deserved hype about Trans-Cascadia wasn’t even about the race, but the culture that was developing around it.

That culture goes beyond race weekend, and was evident when we arrived back at camp. Over beers and spectacular meals, crews discuss their findings, their progress and what’s next. That’s when Alex, Tommy and Nick start to figure out what a course map might look like and how certain trails can be linked together. Not unlike race weekend, professional chefs show up to feed the crew and beer flows without limit.

“The flow of the event is really part of the magic,” Alex says. “How you leave camp, how you get back to camp, things you see along the way. We’re trying to put together the best course possible and share the most fun moments. It’s a constant puzzle of how that goes together, from one stage to the next. It’s definitely an evolving conversation until maybe 30 days before the race.”

Once the final build weekend of the summer is done and dusted, volunteers sit back and relax (and maybe go ride the results of their hard work). But for Nick, Alex and Tommy, the logistics are just beginning.

Hosting a 100-person, multi-day stage race is no easy feat, but when the goal is to tour terrain and trails very few people have ever ridden, there’s a decent chance those trails aren’t in good shape. Since day one, Trans-Cascadia has had no problem putting sweat equity into their chosen terrain.

“That’s the hardest part; when you’re trying to go year after year, you have to find new trail,” Tommy says. “You can’t go back to the same thing—it’s got to be blind. We’re going to do our best to keep it as surprising as possible.”

They’ve looked at archival maps from the 1980s and found old Civilian Conservation Corps trails that had been nearly forgotten. It’s not uncommon for a trail to have 200-plus downed trees across it under such circumstances.

“Last year we opened up a big network in the Sweet Home Ranger District in the Willamette National Forest and that was a big project, like 40 miles of backcountry restoration,” Nick says. “It hadn’t been logged or brushed out in years. What happens with these networks is people find out we’re here, and then the people that ride the stuff start advocating for it.”

Build weekends serve as a means by which to assess the current state of trails in a prospective area. Not only is this a chance for Nick, Alex and Tommy to figure out what’s available, what needs work and what could sensibly be raced on, but it’s also an opportunity to get a feel for the logistics that will go into race week.

“We end up writing 140 percent of the trails we’ll use into our permit,” Nick says. “Once you get out there and start cutting it out, you see how the trails start to form. We’re constantly just talking with the community and trying to find where the cool riding spots are. It’s a lot of map research and a lot of communication with the community and just experimenting on trails. A lot of it doesn’t work out, but a lot of it does too.”

As a race format, blind enduro racing poses a lot of challenges for both organizers and racers. The format Trans-Cascadia uses isn’t unheard of, but in the true style of its organizers, it pushes what most people would think of as being possible. Stages vary anywhere from 15 to 30 miles, some being shuttle days, others being nearly 8,000 feet of climbing and eight hours in the saddle.

“I’ve seen all the things in an event that go wrong,” Nick says. “For me, it was taking all the knowledge of things that I knew I didn’t want in a race and trying to really make those things right.”

For the 2018 running of the event, the crew chose possibly the most infamous volcano in North America: Mt. St. Helens. Starting just outside of the blast zone, racers would make their way through the ensuing stages to the foot of Mt. Adams, on the far east side of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest.

Nick and Alex have spent years exploring the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, but the vastness of the terrain has always been daunting, and rightfully so. But with three years of experience to their credit, they knew the forest had the potential to provide exactly what they were looking for, and they were willing to go all out.

This swath of land and its namesake are uniquely harmonious with Trans-Cascadia. Gifford Pinchot was an American forester, politician and, perhaps most importantly, conservationist—although that wasn’t exactly a thing during his time. Pinchot lived throughout the late 1800s and mid 1900s, when the natural resources of the West were looked at as being infinitely ripe for harvesting.

As chief to the Division of Forestry (which would become the United States Forest Service in 1905) Pinchot’s ideologies and subsequent policies played a pivotal role in the United States conserving land and forests for public use, as well as ensuring future resource extraction kept longevity in mind. The 1.3 million acres in southern Washington that make up the Gifford Pinchot National Forest are stunning, rugged and wild, as are the trails within.

Along with the course map, the masterminds of Trans-Cascadia like to provide entrants with only the information they need to know. This year, racers were given a meeting time and point—a weed farm in northern Oregon—but that’s about it. From there, they were shuttled into the Gifford Pinchot and out of cell service.

By the time racers arrive at camp, a swath of tents is set up not far from a full commercial- grade kitchen and the nicest porta-potties ever seen in the middle of the woods. It’s a backcountry-meets-luxury type of experience and the amenities foreshadow the riding.

“We have our race in late September, when it’s probably going to rain on you a couple of the days, and it may snow. We know how important dirt is in the Northwest, we don’t get amazing dirt year-round, but when it comes, it’s as good as it gets—it’s the best in the world.”

—Tommy Magrath

“We have our race in late September, when it’s probably going to rain on you a couple of the days, and it may snow,” Tommy says. “We know how important dirt is in the Northwest, we don’t get amazing dirt year-round, but when it comes, it’s as good as it gets—it’s the best in the world.”

Every night after dinner (maybe perfectly cooked salmon or a mean ramen made from scratch), the next day’s course is revealed to racers. The first day was 30 miles and 7,000-plus feet of climbing and descending, while day two was three shuttle laps, although not without pedaling. Once racers know a little more about what the following day will bring, they can make a well-informed decision about their nightly antics. While some people go to bed by 10 p.m., others keep the good times rolling well into the morning.

As for those who are doing the partying (or lack thereof ), there’s no one type. Trans-Cascadia attracts everyone from overseas race zealots to pro athletes to fitness-fanatic dads to the entire Santa Cruz Syndicate, a team comprised of multiple World Cup DH and enduro athletes.

And because it’s blind racing, everyone’s on a leveled playing field.

Along with the 100 or so racers that come for the week, a near equal number of volunteers shows up. Medics, stage martials, on-course timers, lunch cooks, dishwashers, evening bartenders and logistic support people do all they can to make every moment a smooth and enjoyable experience for the racers.

On the day camp was moved this year, it was an eight-hour endeavor. As soon as the day’s shuttles left, 120 tents were broken down, every racer’s personal bag was collected, the kitchen was disassembled and packed into a semi-truck, the toilets were hitched up and the entire camp hit the road, caravanning to the next locale. Barely in time to meet the first finishers, everyone—volunteers and racers alike—jumped in to help where they could.

“The race doesn’t happen without volunteers, and the community that surrounds the race has carried it from the onset,” Alex says.

By the end of the week, exhaustion is inevitable. But as racers cross the finish line of the final stage on the final day, relief trumps fatigue and everyone manages to celebrate over beers and the bottle of tequila that’s passed around. Fully drained and still partying—that’s Trans-Cascadia’s style.

Every single rider, no matter their proficiency, has just experienced the same exact thing, which is something they can connect through. The collective buzz from five days of riding spectacular trails feels like the rumblings of a volcano. The aftermath, however, is no St. Helens. Instead, it’s an unforgettable adventure and damn impressive trails, for the racers as well as the region through which they’ve ridden.

“Seeing people come though the finish line at the end of every day, they’re excited because they experienced amazing trail and amazing comradery,” Tommy says. “But there’s also a little bit of survival, there’s this let-go of emotion, like, ‘I’ve made it,’ and that’s an accomplishment.”

![“Brett Rheeder’s front flip off the start drop at Crankworx in 2019 was sure impressive but also a lead up to a first-ever windshield wiper in competition,” said photographer Paris Gore. “Although Emil [Johansson] took the win, Brett was on a roll of a year and took the overall FMB World Championship win. I just remember at the time some of these tricks were still so new to competition—it was mind-blowing to witness.” Photo: Paris Gore | 2019](https://freehub.com/sites/freehub/files/styles/grid_teaser/public/articles/Decades_in_the_Making_Opener.jpg)