Helping Hands Elite Mechanics Blaze a Path for Women

Words and Photos by Anne Keller

Paige Stuart is disarmingly considerate, even at four o’clock in the morning. Between offering coffee, checking last-minute notes, chatting with racers, and forcing down some cereal, the petite 44-year-old is cleaning the kitchen.

Stuart is an elite race mechanic tasked with working on bikes for some of the best riders in the world. But right now, in the few idle moments between tasks associated with guaranteeing that multiple intricate machines will function flawlessly for the entirety of the Leadville 100 cross-country race, there is a dirty kitchen, and since no one else is stepping up to the task, Stuart does dishes.

One racer, known for his late arrivals, asks Stuart for a few adjustments on his bike. This should have been handled the previous day but, with the kitchen now tidied, Stuart grabs her headlamp and in the soft glow of an antique lamp, goes to work. The signs requesting no food or drink say nothing about bike repair, so the lavishly decorated Victorian parlor of the team’s Airbnb has turned into a temporary equipment storage room. Stuart makes the necessary adjustments. If there’s any hint of annoyance with the early morning ask, it’s imperceptible.

It’s still dark on this mid-August morning in 2023 when she rolls the first of several bikes out to the starting corral in downtown Leadville, Colorado. Low-lying clouds take their first visible shape in the sky—robust and heavy as they spit a light rain onto the crowd gathering below.

For as long as there have been organized, professional mountain bike races, there have been race mechanics. In the grassroots early days, “racer” and “mechanic” were often one and the same— the self-reliant ethos inherent in mountain biking spread naturally to racing. But as bikes grew more complicated and races began being won by increasingly slim margins, the separation of roles began. The duties of an elite race mechanic today are highly specialized and must be performed with precision. Most of the race scene’s top wrenches cut their teeth in shop jobs or as company technical staff.

The job is demanding and involves a commitment to long hours. Beginning before daybreak and ending late into the night is commonplace. It is also largely a solo pursuit. Extended stretches of time are spent in an empty garage, back porch, or team van while the racers, team managers, and other support staff can schedule activities during routine hours. It is cracked knuckles, dirty fingernails, shared hotel rooms, missed sleep, and skipped meals. It is also an overwhelmingly male-dominated profession.

Jen Klish knows this all too well. The Sacramento-based anesthesiologist spent a year wrenching on the NORBA and World Cup circuit in 2000. Despite the heyday that American mountain bike racing enjoyed during that era, Klish was the sole female wrench.

“During those years, you’d sometimes see women changing their flats, doing basic repairs, but no one was working on their suspension, building wheels, or doing the more complicated fixes,” Klish said. “And there were definitely no other women wrenching on the circuit in official roles.”

Twenty-three years later, and despite significant growth in participation of women in recreational cycling, competitive racing, media, and industry positions, not much has changed when it comes to team mechanic roles. There are currently only two U.S.-based women working on the professional mountain bike race circuit.

The Leadville 100, which in 2024 is hosting its 29th edition, is considered one of the most prestigious in the U.S. Each of the nearly 2,000 participants must qualify for the event and, for the pro field, the race’s inclusion into the Lifetime Series marks it as a competitive must-do for the cross-country elite.

In 2023, Stuart arrived on site two days prior to the race, immediately readying bikes for the three Liv/Giant athletes that she is responsible for. All are legitimate contenders for a winner’s jersey, which makes Stuart’s role all the more crucial. She works out of a 24-foot Sprinter team van parked in front of the rental house. Outfitted with shelves of tires and wheels, a full workstation, tools, and an air compressor, the van is her mobile repair shop for the weekend.

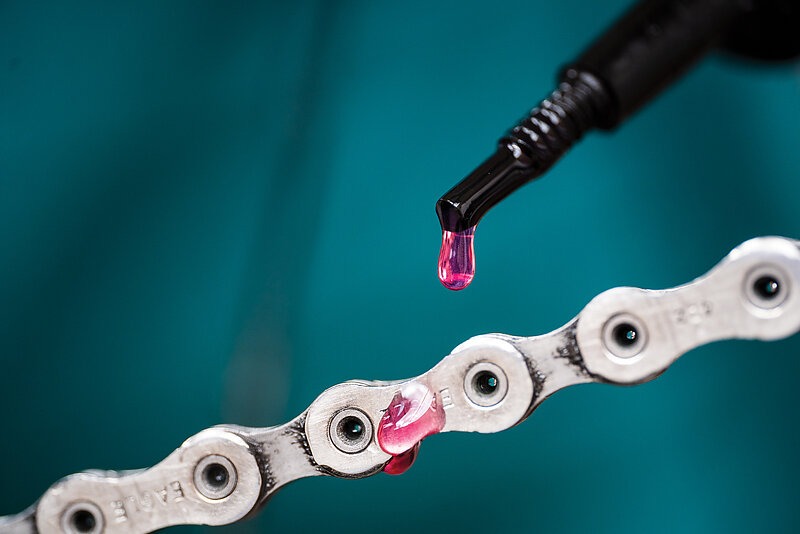

As evening turns to dusk, Stuart kneels on the sidewalk and changes tires. Sealant oozes off her hands and collects on the pavement like a child’s melting ice cream cone. It’s 8:30 p.m. when she stops to eat dinner before going back to work. An afternoon downpour the following day forces Stuart under the cover of a pop-up tent as she finalizes her bikes. With her collar pulled up and taking frequent pauses to warm her hands, she trues wheels, pulls and cleans cassettes, and adjusts suspension for the specifics of the racecourse.

Early in the morning on race day, team managers, mechanics, and support crew jockey for position in the tight starting corral. They act as place markers while the racers take warm-up spins on secondary bicycles. At 5:45 a.m. the sky continues to impart a soft rain. Wind occasionally whips through the venue, foreshadowing a day defined by a certain moodiness permeating the event. The starting gun is fired at 6:30 a.m. and the racers sprint to begin a grueling 106-mile journey. As they ride away, Stuart hurries from the starting gate to the team van and inches in line with traffic on Highway 24 toward an aid station at mile marker 50 where she’ll park for the better part of the day. Her mug of coffee, now several hours old, has turned tepid in the mountain air.

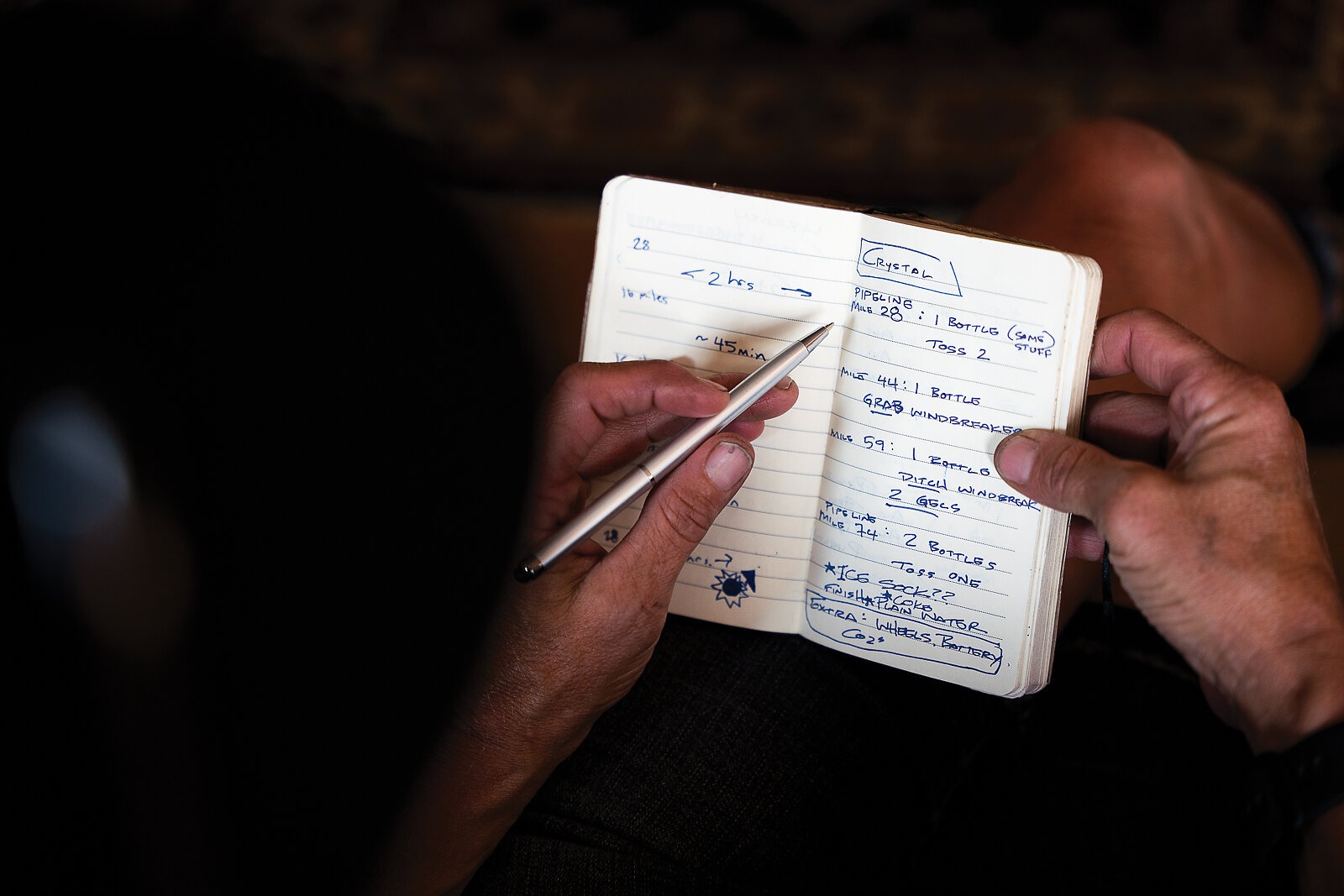

Later, in an open, high-desert field dotted with sagebrush, Stuart checks her notes, then her watch, and then cranes her neck around spectators to peer out at the course. Underneath her team tent, tools are neatly organized on a folding table. A pink notebook sits out. In it, Stuart has written notes detailing the bike set-up measurements of each of the team’s athletes along with lists of approximate times that they should pass through each aid station. The racers wear an electronic chip and, as they pass by timing markers, their locations are broadcast online. Those who track close to their expected times are assumed to be having a clean ride with no issues. For Stuart, a “boring” race day typically means a job well done.

Stuart wasn’t always mechanically proficient, although she was raised in a household that both valued and modeled that skill set for her. The mechanic bug came later for her, in her early 20s while living in Salt Lake City, Utah.

“I scored this old Schwinn Sting-Ray from the thrift store for stupid cheap. It was rusted, none of the bearings spun, the bottom bracket didn’t spin, and I completely disassembled it and figured out how to fix it. I was able to get it working perfectly again, and I got a lot of joy out of that,” Stuart said. “I got to tell people how I basically resurrected it from the dead. And then I just started hoarding thrift store bikes and fixing them up for my friends— sending them out into the world to live again. That’s how it all began for me.”

After relocating to Moab, Utah in 2011, Stuart attended UBI (United Bicycle Institute) for her own personal education. She was an avid cyclist and realized that modern technology, such as disc brakes and suspension, were out of her league, but she wanted to be able to fix her own bikes. She finished the course and was immediately cold-called by a bike shop.

After a year of trial by fire, Stuart sought out work at the Chile Pepper Bike Shop, one of Moab’s preeminent shops, to learn from some of the best in town. She stayed at Chile Pepper and moved up through the ranks until eventually being offered the service manager position. Her promotion was short-lived as she soon received a call from Liz Walker, the global sports marketing lead for Liv Cycling. The company’s race team was looking to fill a mechanic role and Stuart had been recommended.

“My first day on the job Liv flew me straight to Europe to work a World Cup race,” Stuart said. “It was insane, I don’t even know how to describe it. I was fresh out of Moab basically just riding with my friends not really paying attention to the race scene and then, there I was.”

Stuart made a great impression and went on to become Liv’s primary circuit mechanic. When Walker transitioned to working as Liv’s team manager, she intentionally set out to hire women to fill the roles supporting their race program.

“I thought that with viewing the race program as an extension of the marketing of Liv Cycling, why not hire the professional staff to match?” Walker said. “It just seemed to align with what else we were trying to do.”

When she hired her, Walker knew Stuart had never wrenched at the World Cup level before, but she was more interested in finding someone teachable who had the soft skills necessary to develop into the role. To funnel women into these positions, Walker knew some of the roadblocks needed to be removed. At a World Cup race, she was once approached by another team manager who apologized for not having any women on the staff of his team.

“He said, ‘I tried, but I just couldn’t find any that were qualified,’ and I was like ‘ding, ding, ding, that’s the problem.’” Walker said. “You don’t become qualified until someone gives you the opportunity, and that takes a lot of bandwidth. You need someone to create the environment and offer the level of support to coach someone into experience. If that’s not your primary motivation, then, of course, it is going to be really hard to find.”

An hour’s drive north of Leadville sits the town of Breckenridge, which hosts the annual Breck Epic stage race, a six-day suffer-fest with a combined elevation gain of nearly 40,000 feet over 250 miles of racing.

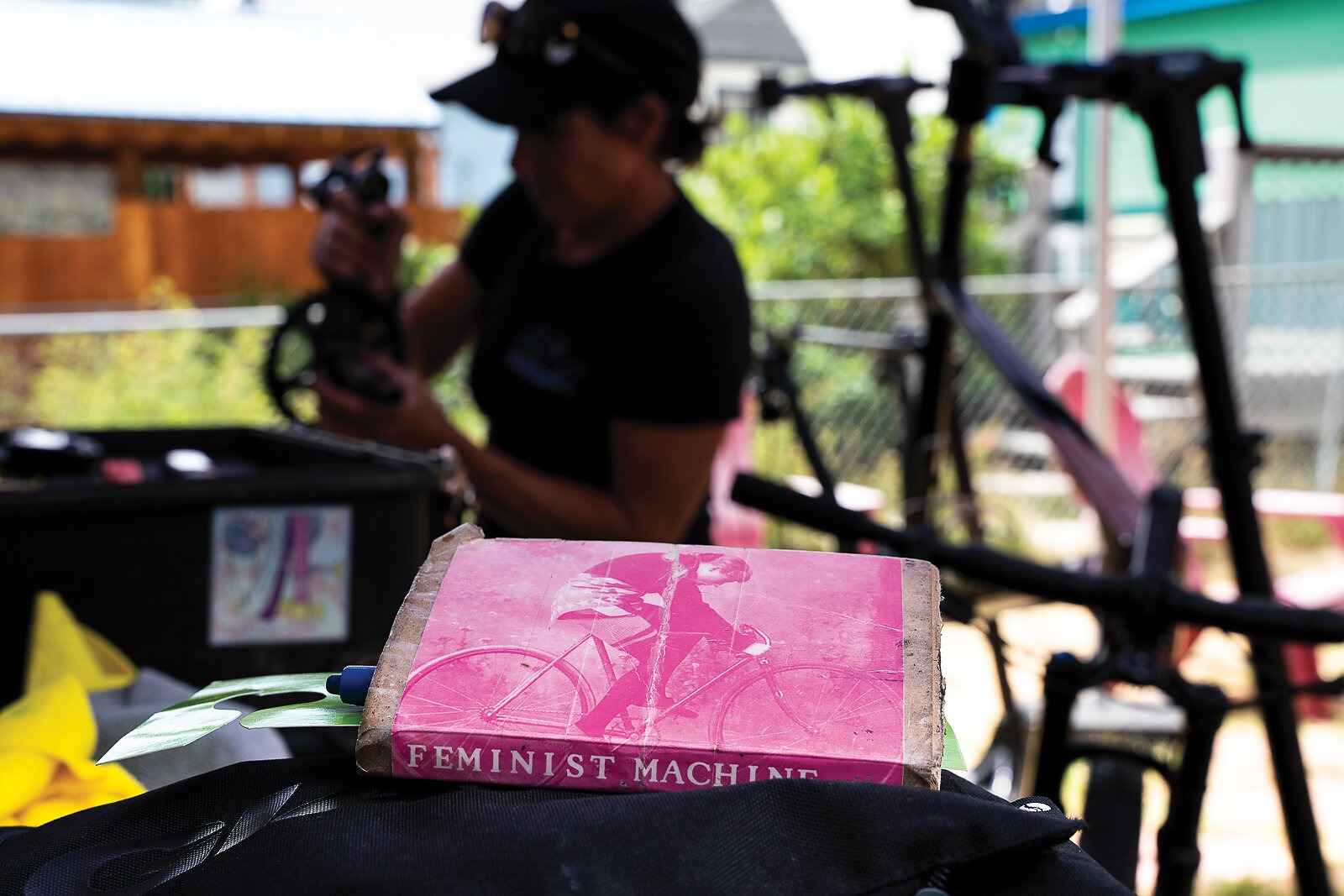

Andi Zolton unpacks a power washer from the back of her car. While possibly overkill for cleaning a bicycle, it’s much more effective than a garden hose. Between a full tool kit, extra tires, a bike stand, cleaning supplies, and spare bike parts, her car is packed to capacity which renders her rearview mirror useless. Zolton, wrenching for three professional racers on the Juliana team, didn’t score the team van for this event, so her compact Hyundai hatchback must serve as a temporary repair shop.

The challenging terrain of the Breck Epic presents a logistical quagmire for team staff and support. Accessing aid stations requires creativity and a knack for problem-solving that, if not properly planned for, could leave a racer stranded. For Zolton, reaching the first aid station meant strapping a spare set of wheels to her back, loading a pack with tools, and hiking the remaining two miles from the trailhead.

At the team house before the first stage, Zolton pulls on a pair of bright fuchsia dish gloves and goes to work cleaning bikes. A bucket of soapy water sits at her feet as she fires up the power washer. It’s an efficient process, but it leaves her drenched. Once cleaned, she spends the next few hours meticulously detailing the bikes. She lightly sandpapers rotors for better braking grip and removes pulley wheels from the rear derailleurs, cleaning them delicately by hand. It’s time-consuming and a technicality that most would overlook, but not Zolton. This level of attention is partly driven by what she believes represents quality work, but it also comes from a place of genuine care. The most rewarding part of the job, she says, is the connection built with her riders.

“Obviously it matters to me if they win or lose, but what is more important to me is the human connection, the trust that I get to build, and how it can impact race day,” Zolton said. “If I have built up trust and fostered that connection and I know that I have done the best job I can, seeing that translate to confidence from the team is the most rewarding part.”

For the better part of the evening, Zolton works alone in the garage. The racers, in varying stages of resting and showering, occasionally stroll in, clad in sweatpants with towels wrapped around their hair. Sometimes they offer food. Sometimes, just company. With three bikes to maintain, Zolton finishes the evening by headlamp.

Watching Stuart and Zolton, it’s undeniable that they both possess a high level of competence in their respective positions. They are expert mechanics and have extensive technical knowledge. Their professionalism forces several questions to the surface. Namely, why should gender be a limiting factor for anyone filling this role? Why are there not more women bike mechanics?

“It’s hard to dream about being something you’ve never seen before,” Walker said. “The bike industry was never built around women or any underrepresented population, so very few can see themselves in those roles. We have to bring people into positions and support them in those positions so that there is a greater chance for more people to see someone like Paige and believe that they too could carry that title.”

In recent years, women have begun making inroads to filling mechanic roles at shops. After Stuart took the job at Chile Pepper in Moab, she noticed that over time more women were applying for its wrenching positions. This interest also prompted a popular once-a-month Women’s Mechanic Night hosted after hours. On those evenings, a packed house of participants could be found, bubbly water in hand, eating slices of pizza and engrossed in whatever technical topic Stuart was discussing as she held court at a repair stand. Questions came freely, the welcoming environment conducive to the airing of any passing query, regardless of experience or mechanical proficiency. This is not a scenario exclusive to Moab; the popularity of women’s mechanic nights throughout North America has skyrocketed.

While the shop scene could be viewed as a wellspring of ideas that dictate the direction of the mountain bike industry as a whole, at the elite level this growth has yet to meaningfully translate to the race circuit. For Walker and Stuart, the disconnect between shop interest and professional race wrenching is part of a larger societal narrative.

“For a very long time there has been this unfair domestic burden placed on women that has prevented them from taking on roles where you might be traveling for half of the year,” Walker said. “If you have a family at home, what are the chances that your partner is going to stay home and take care of the kids?”

Stuart shares a similar view of the phenomenon and believes that any talk of increasing the number of female race mechanics should include “a deeper discussion about gender equity and opportunity.”

This broader societal narrative encompasses the expectations placed, however nuanced, on women in the workplace, in which positions are typically validated. Historically, on the race circuit, women working as support staff filled roles such as soigneur (a term adopted from road cycling that describes someone whose job is to provide massages, physical therapy, or assist with training and other off-the-bike tasks) or as a team chef. In bike shops, women are often directed toward the sales floor.

Stuart, Zolton, and Klish all say that from a team race mechanic standpoint, they’ve felt supported and encouraged by their male counterparts. The level of respect toward these women from their racers is also apparent. In a broader shop context though, the general public does not always show as much encouragement.

“When I first started working at the bike shop, I would literally have guys look straight over my head and be like ‘I need to talk to a mechanic,’” Stuart said. “I had this one older man walk back into the service area and try to physically pry a tool out of my hand. It was infuriating.” With more women filling shop roles, many are hopeful that this dynamic will soften, but the potential bad taste it leaves can reverberate and alter future career choices.

“Without change, at some point, perhaps women are going to get fed up and look at this and think, ‘This is not a place for me.’” Walker said.

After threatening all day, the sky in Leadville finally opens up to deluge racers as they start to cross the finish line. The crowd of spectators scatters to seek shelter under any available awning while team staff members dig through their backpacks for rain gear. Stuart pulls on her Liv team jacket as a handful of top men sprint down the roadway toward the line. She’s kept track of the standings throughout the day but it’s hard to forecast how the finish will unfold. She has another hour and a half on course before Anthony, a leading contender in the women’s field, will complete her race. Stuart talks with the Team Giant racers as they come in, grabbing bikes while they pose for photos and accept their medals. Then she waits as the rain continues to fall.

When Anthony crosses the line in 6th place, the impact of the cold, wet weather combined with severe physical exertion has taken a toll and she partially collapses as she comes to a stop. Stuart catches her and her bike, the two making a strange pair as the taller racer is steered through the crowd, held up by the five-foot-one-inch-tall mechanic. The shock of Anthony’s exhaustion begins to slowly calm, but it underscores the definition of support in Stuart’s checklist of responsibilities.

When the final racers stagger in and the last of the course tape comes down, the anticipation of the weekend fades to memory. Dusk looms and the race venue, so congested earlier, is empty now. An occasional burst of wind picks up a stray number plate, sending it fluttering across the ground.

After the initial celebration, there’s nothing to do but pack up. Tool satchels are rolled, pop-up tents folded away, bikes disassembled and tucked into travel bags, and rental houses cleaned. Mechanically, Stuart earned a perfect score: All bikes worked with no issues.

“In the downtime between races, I might restock my supplies or order a new tool that could make me more efficient at my job,” Stuart said, sitting quietly for a minute to bask in the success of the past few days. “I’ll definitely ride my bike.”

The reflective calm is short-lived though. Stuart has tools to pack. She stands up and gathers her belongings. Planning for the next event has commenced.