Ghost Trails Reclamation and Revival in Northern California

Words by Kurt Gensheimer | Photos by Scott Markewitz

Looking through the hand-blown glass window, the world outside the old mining cabin appeared wavy and distorted.

It snowed relentlessly for hours, turning the meadow surrounding the cabin into a blanket of white; an odd contrast to the neighboring aspen grove still sporting bright green leaves.

It was a freak late-September snowstorm, the first snowfall of the season in California’s Northern Sierra Nevada Mountains. Across the warm cabin sat Eric Porter, my partner for this week-long adventure into the “Lost Sierra,” a section of the range between the towns of Downieville and Quincy. We were on a mission: to hunt down and ride as many of the area’s “ghost trails” as possible.

The moniker is deserved, as these primitive ribbons of dirt weren’t built for recreation. They were originally carved during the Gold Rush of 1849, when tens of thousands of prospectors combed the rugged Sierra Nevada terrain in hopes of striking it rich. For these men, “recreation” meant drinking whiskey at the saloon after a soul-crushing day of work, and the trails were a means of survival, to transport tools, horses and ore from their remote mines. For us, they represent a means of escape from the mass of humanity and the daily grind, a therapeutic release to connect with the environment. If we could find them.

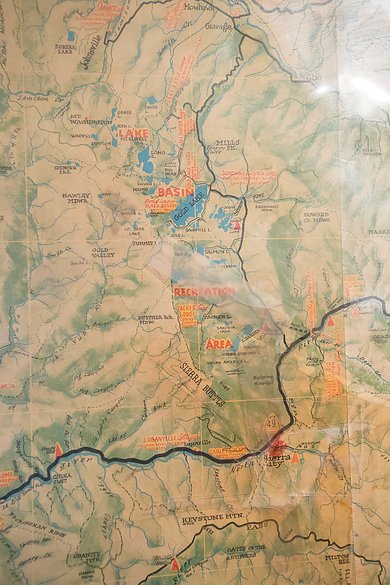

The Lost Sierra was one of the epicenters of the Rush of ’49, and left hundreds of miles of trail crisscrossing the area. Once, they connected dozens of mines, mining camps and communities, now long abandoned, but very few of the trails can be found on modern maps. However, one map still shows many of these prospector paths. It can’t be found on the Internet and isn’t in any books. It’s hanging on the wall of the Red Moose Café in Sierra City, CA. Like a two-wheeled treasure map, it’s what inspired a three-year quest to find and ride the ghost trails of the Lost Sierra.

I first noticed the Red Moose Café’s map while having breakfast at the bar one morning. Not recognizing many of the trails, I asked Steve, one of the restaurant’s owners, where he’d gotten it.

“It was here when we bought the building,” he said. “It’s a Sierra County Booster map from 1954. I’ve been exploring the Lost Sierra since childhood, and there are old mining trails on here I’ve never seen on other maps.”

I was hooked, and over the next three summers I searched for these ghost trails. Many are near-nonexistent, having been reclaimed by nature. Others are passable, but could only be found by spending time hunting through the woods and engaging with the community members who worked hard to keep them open.

Ghost trails are an acquired taste because they ride differently than most modern trails. Rogue sticks litter the trail bed, a thick layer of pine needles makes the surface soft and slippery, and loose rocks jump violently against your downtube, or worse, your shins. Switchbacks are steep, tight and numerous. Sometimes the trail is so faint you’re essentially freeriding through the forest, and climbing is particularly challenging thanks to a perfect combination of steepness and lack of traction. Having to hike-a-bike is common and serves as a sort of gatekeeper—only the most fit and motivated are willing to do it, but the rewards almost always justify the hump uphill. Once you’ve adapted to these primitive conditions, everything else feels tame.

The toughest part of riding ghost trails is simply finding where they start and finish, as often what’s clear on a map is completely hidden on the ground. But there are other ways to find and follow them.

The toughest part of riding ghost trails is simply finding where they start and finish, as often what’s clear on a map is completely hidden on the ground. But there are other ways to find and follow them. Back in the 1930s, the U.S. Forest Service employed an army of Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) woodsmen to mark and inventory every trail on public lands. As crews hiked or rode horses down each, they signaled their path by regularly cutting “blazes” into abutting trees. A blaze looks like a lower case “i,” a roughly eight-inch vertical rectangle topped by a two-inch rectangle, cut at eye level into the bark with a hatchet.

The bright, exposed wood of a blaze can be seen from a distance, even through thick forests with heavy underbrush; useful on trails so narrow and primitive that without aboveground markers you could completely lose the path. Such cuts eventually lined thousands of miles of trail across the American West, earning CCC crewmembers a new nickname: “trailblazers.”

For the modern explorer in the Lost Sierra, blazes also provide chronological direction. Since the practice of chopping them into trees is no longer accepted, only old trails will be accompanied by blazes—assuming they haven’t disappeared under a century of regrowth, and that the marked trees didn’t fall over long ago. The blaze is merely a guide; sometimes you must rely on instinct to follow these forgotten trails.

Not all of the Lost Sierra’s ghost trails have been completely forgotten. A few days before our blaze hunting led us to the snowy mining cabin, we were on the Sardine Lake Overlook Trail, an old prospecting path in the shadow of the Sierra Buttes. It’s also a Lost Sierra classic, thanks to its creek-bed rockiness and full views of both Upper and Lower Sardine Lakes. After climbing from nearby Tamarack Lake, the trail’s initial descent begins with a series of steep, tight and loose switchbacks—difficult in general, but even more intimidating considering you’re 1,000 vertical feet above Sardine Lake. Taking in the view while riding isn’t an option, as the trail commands attention, but you’ll stop because the towering granite spires of the Sierra Buttes command even more.

It’s the type of awe-inspiring terrain usually reserved for wilderness areas or National Parks, where mountain bikes aren’t permitted. But the Sierra Buttes are different. Evidence of the area’s days as a major gold producer are everywhere along the trail, from old mining equipment to massive stone foundation walls. Because of this, every trail around the Sierra Buttes and through the alpine beauty of the nearby Lakes Basin (except for the Pacific Crest Trail [PCT]) are legal for bikes. Located just north of the Buttes, the Lakes Basin is not for everyone, as a 10-mile ride in the area can often take three or more hours due to the steep, technical terrain. But those willing to push their fitness and skills will find dozens of alpine lakes set under the Basin’s giant cliff walls, ample reward for the suffering experienced in every climb.

As we’ve learned on this trip, all trails come and go. Such was the case with Deer Lake Trail, another old prospecting trail along the Sierra Crest. Dropping south off the Crest toward Pack Saddle Campground, Deer Lake is three miles of narrow, rocky and technical descending, broken up by numerous log drops and with incredible views of the Sierra Buttes. It’s a truly primitive backcountry experience, but one that was recently lost to the mountain bike community. As part of a reroute plan, Deer Lake was slated to become part of the PCT, and thus hiker-only. But not without compromise, as the move would also open nine new miles of singletrack to mountain bikers.

In a coincidental twist of fate, we also happened to be the very last mountain bikers to legally ride Deer Lake Trail, as the day we rode it was the same day as the USFS closure. Never have I had a more bittersweet riding experience; it was like a final dance with an old friend. My sense of melancholy was amplified as we reached the end of the trail and passed the USFS trail crew in the act of hammering the new PCT sign into the ground.

Jamison Creek Trail, at the northern terminus of the Lakes Basin, is another of the region’s seldom ridden icons. Dropping 2,000 feet in just over three miles, the trail takes riders from the high alpine of the Sierra Crest to the historic mining community of Johnsville, serving up remarkable views while requiring laser-focus. The beginning is steep and loose, winding past a trio of alpine lakes below Mount Elwell’s enormous rocky spires; halfway down, the scree turns to loam as it dives into seas of wildflowers and stands of aspen. Grassy Lake marks the final half-mile, where matters get serious—a gauntlet thick with ultra-chunky rocks and big stairsteps that push the limits of suspension. The choice to roll, air, or send each feature is up to the rider; just look before you leap, as this final section has claimed numerous collarbones.

Every old trail in the Lost Sierra has its own characteristics; no two feel or ride the same, and even that can change depending on the weather. The snow wasn’t the only anomalous weather we experienced, it was just the most recent. Conditions ranged from a sunny, “sun’s out, guns out” day on Sardine Lake Overlook, to gloomy fog and cold drizzle on Deer Lake, to three inches of snow and subfreezing temperatures on Jamison Creek. The snow came down harder as we pedaled toward the warm cabin, wondering what other surprises hid in the whiteness ahead.

While the map at the Red Moose Café may be webbed with forgotten routes, modern trail maps of the Lost Sierra are far from empty. Some 80 years after the CCC crews passed through the area, a new generation of trailblazers are putting their own marks on the landscape: the nonprofit trail-building and habitat-restoration group Sierra Buttes Trail Stewardship (SBTS). Founded in 2004 as a three-person volunteer group, SBTS now employs 40 full- and part-time staff—86 percent of whom live in either Plumas or Sierra counties—and maintains more than 800 miles of trail.

Considering the recent history of the area, that’s an impressive and important statistic. Along with Alpine County, Sierra and Plumas are two of only three counties in California that have shrunk in population over the past 15 years. Towns in the Lost Sierra continue to struggle economically, which makes SBTS’s efforts even more critical to help families put food on the table and help local communities maintain their way of life. By combining the therapeutic power of a trail experience with preserving important historical routes, SBTS is providing strength through heritage, for all ages. In 2017 alone, the 13 students in SBTS’s youth programs earned 39 skill certifications and maintained more than 10 miles of trail.

“Our children are the future of land stewardship and our mountain communities, so it’s important to instill a sense of pride and ownership of trails with them,” said Greg Williams, SBTS executive director and cofounder. “It also gets kids outside where they can be kids, playing in the dirt, learning about ecosystems and becoming better human beings.”

One of the community’s biggest trail developments was completed during the summer of 2017, when SBTS, Sierra County Land Trust, Tahoe National Forest – Yuba Ranger District, and the Pacific Crest Trail Association partnered on a historic reroute of the PCT. The project was nearly 10 years in the making and included six new miles of legal mountain bike and motorcycle singletrack on a decommissioned portion of the PCT, enabling riders to connect Packer Saddle with the infamous “Baby Heads” descent to Pauley Creek.

The project also expanded legal access for mountain bikes to the Sierra Buttes Overlook Trail by opening a 1,500-vertical-foot section that shared an alignment with the former PCT. Dubbed “Tower 2 Town,” the ride nowvdrops from the 8,591-foot summit of the Sierra Buttes to the town of Downieville—a total of 7,000 vertical feet over 18 miles, making it one of the longest continuous descents in North America.

“We want our community to be the model for welcoming all outdoor enthusiasts, and we’re building it one trail at a time in the Lost Sierra.”

—Greg Williams

“This was a huge community effort that will benefit all trail users, motorized and nonmotorized,” Williams said. “We want our community to be the model for welcoming all outdoor enthusiasts, and we’re building it one trail at a time in the Lost Sierra.”

The heavy snowfall continued as Eric and I searched for refuge to escape the storm. Eventually we saw candlelight across the meadow, flickering like a beacon through the windows. The smell of a warm fireplace and the sound of laughter grew as we pedaled up to the front door, swinging open with a welcoming hurrah.

Mark Weir, Marco Osborne and Ryan Finney had awaited our arrival all afternoon, drinking and telling stories while Frank Gulla prepared a feast on the stove above the fireplace. All four share a deep connection to the area, and part of their conversation centered on the next generation of local riders. Between the magic of the old cabin and the freak September snowstorm, it is the perfect place to dream a little and create a vision for the future of the Lost Sierra.

Part of that vision is ensuring the strength of the area’s history and community, and they all feel the ghost trails are central to keeping both alive. These old, elusive pathways are more important than ever, because they provide a passage through time and a sense of pure, raw, rugged adventure that modern trails lack.

By reviving these ghost trails, modern riders will also give them a fresh-yet-familiar purpose: reconnecting Lost Sierra communities through exploration. Not a quest for gold or material riches, but one of self-discovery— a form of balance in an unbalanced modern world. For the hardy miners who built them, these trails served as paths out of the wilderness. More than 160 years later, they offer a different community the chance to stay in the wild; a way for the people of the Lost Sierra to remain in the mountains they call home.