Filthy Rich A Century of Wealth in Western BC

Words by Sakeus Bankson

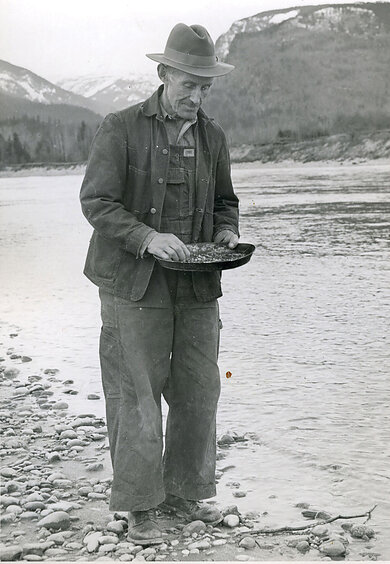

There was little glamorous in the life of a miner in the mid-1800s. Driven by dreams of instant wealth, swinging a pickaxe hundreds of feet underground in darkness only broken by candlelight, some went insane from the isolation. Some died in avalanches or accidents. Almost all walked away with nothing but wasted months or even years.

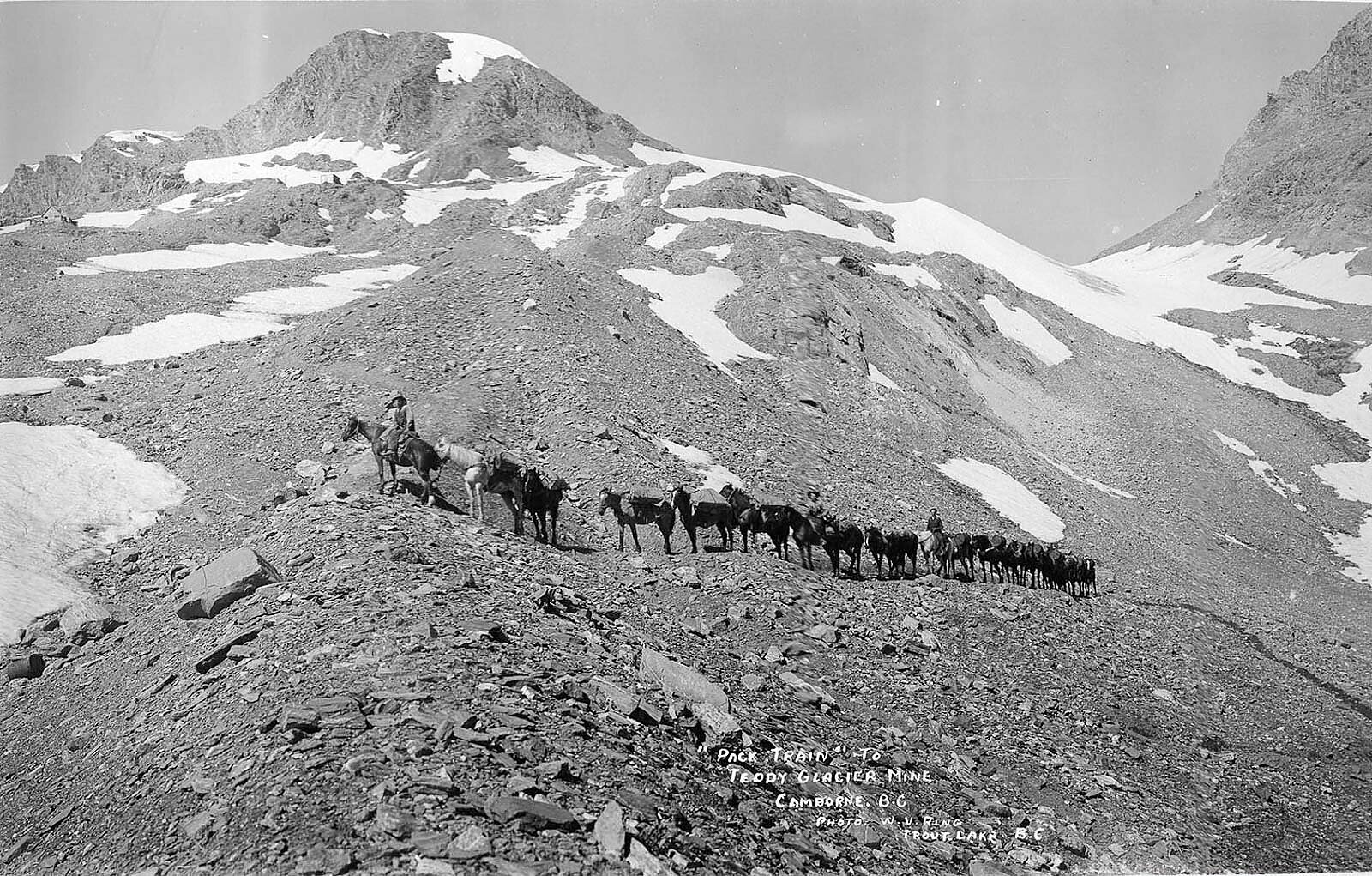

The West Kootenays was an exception. In the deep tunnels pocking the lonely hillsides, those miners discovered the glimmer so many had tried and failed to see—the glitter of gold and silver. After years of searching they had found their glamour, and soon wealth began pouring out of the region in the millions, and the accompanying railroad and logging industries (as well as sketchy land acquisition schemes) boomed alongside the mines puking bright orange ore. There was money in the hills, and the rush to cash in pumped through the region like a frantic, shimmering heartbeat.

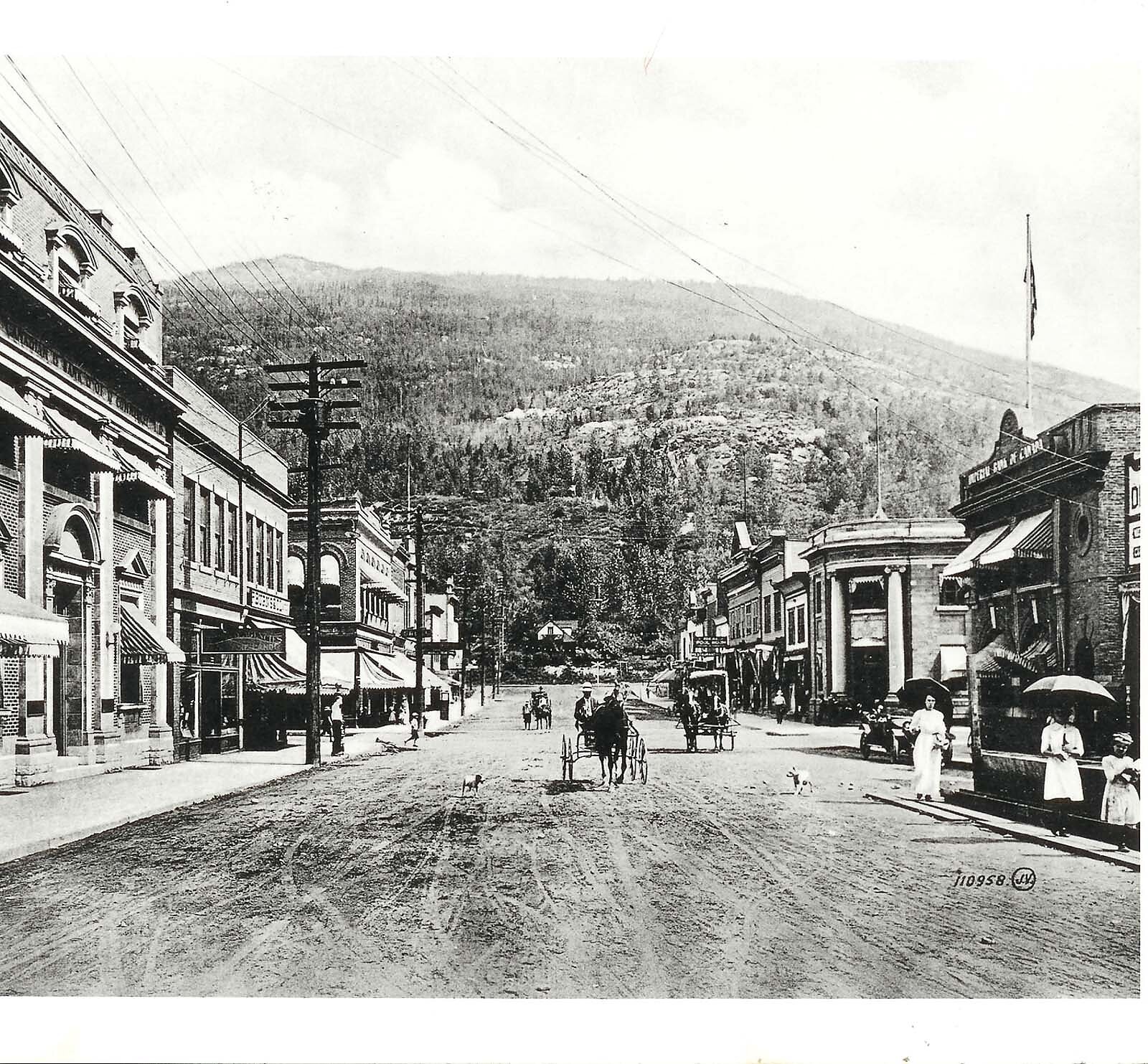

After decades as frontier mining camps, by the 1880s the towns that had sprung up to support this influx were becoming the largest in western Canada. By the turn of the century Rossland could claim 42 saloons, Nelson two major rail lines, and Revelstoke a YMCA, opera house and Hume Department Store. The West Kootenays were no longer a remote backwater—it was one of British Columbia’s hottest locales.

But, as is inevitable with most communities built on a mining boom, by the early 1900s things had started to slow down. However, lumber, railroads and a steady stream of mining kept the area and its major towns alive—and created the logging and mining roads that the first West Kootenay mountain bikers would careen down nearly a century later.

While nothing on the area’s mining legacy, mountain biking would officially creep its way into the West Kootenays relatively early in the sport’s history. In 1985 the first Rubberhead Festival was held in Rossland, a fully rigid rattle-fest where riders blasted along the town’s growing network of XC trails and clattered down nearby wagon roads. Eight years later, Rossland would host the 1993 North American Championships. In the slowly emerging North American bike scene, the West Kootenays were on the map.

Mark Holt, owner of Nelson’s 19-year-old Sacred Ride a bike shop, has seen the West Kootenay’s notoriety grow since the early ‘90s—in fact, as possibly the most prolific trail builder in BC, he’s largely responsible for it. The former Montreal-ite arrived in Nelson via Whistler in 1992, where he immediately began riding his Rocky Mountain Summit hardtail and scratching in trails. Over the next two decades he can be credited with over 50, including some of Nelson’s most famous. However, in the early years Holt and friends still frequented Rossland—even if few others did.

“Rossland had a bunch of rad riding for that era, and we used to go there all the time,” Holt says. “Still, it wasn’t like the coast at the time. They were the self-proclaimed mountain bike capitol of Canada, but there was nobody there.”

“It wasn’t like the coast at the time. They were the self-proclaimed mountain bike capital of Canada, but there was nobody there.”

Meanwhile, in the dusty terrain of nearby Kamloops, a knobby, two-wheeled monster was growing. With snowboarding booming and skiing in the midst of the “extreme” movement, a group of riders began approaching mountain biking with that same rebel attitude. With the backing of Vancouver’s Rocky Mountain Bikes, the “Fro Riders” need no introduction: Wade Simmons, Brett Tippie and Richie Schley are the undisputed godfathers of freeride mountain biking, and when they began including the West Kootenays in their “Kranked” movies the area was suddenly on a completely different radar.

“Mountain biking really kicked in here around 1997 or ’98 with ‘Kranked’ and then the New World Disorder films,” Holt says. “It had always been Rossland—now we had folks coming to Nelson, specifically to ride.”

The popularity of the West Kootenays, especially Nelson (in large part thanks to Holt’s ceaseless building), surged among the newly emerging freeride mountain bike scene. The steep, techy descents and twisting skinnies from the films generated all sorts of interest, and soon riders were showing up in droves—a relative term compared to places one the coast like Whistler and the North Shore. As the later 2000s rolled in and the type of in-vogue styles changed, the West Kootenay’s popularity once again ebbed.

“The community has definitely grown over the years, but there’s definitely been quiet stretches,” Holt says. “Just a couple years ago, especially in the early 2000s, I’d show up to work and people would be lined up at the door looking for trail maps. But we don’t get that as much anymore.

In recent years, however, the mountain bike industry has exploded, a combination of user-friendlier bikes and folks searching for a new way to enjoy the outdoors. Nestled in some of British Columbia’s most impressive mountains and surrounded by views and terrain to rival any in the world, the “outdoor experience” was something the West Kootenays has been known for since long before white settlers arrived. And so as bikers searched for new places to ride, it was almost inevitable they’d rediscover the West Kootenays.

“The area has definitely been on the map for a while and I think it’s going to keep growing, if slowly,” Holt says. “I don’t think it will ever be anything too big because we’re so far away from everything, but it hasn’t slowed down in 20 years.

One of the benefits of being hours from everything is unsullied variety—the differences in terrain and fauna between Rossland and Revelstoke can be quite dramatic, and each offers its own flavor of riding disciplines. Rossland is known for its long heritage of XC, and has more recently seen a boom of intermediate flow trails and more newschool riding style. The jewel of the area, however, is the Seven Summits Trail. The monumental 20-plus-mile ride opened in 2004; a mere three years later, it had earned Bike Magazine’s coveted “Trail of the Year” award.

Over the past decade, it’s Nelson that’s become the hub of mountain biking in the West Kootenays (as Holt puts it, “Where else can you drop 3,000 feet to a BBQ, beers and bikinis on a beach?”). Famous for its old-school technical descents and expert-level freeride trails—including the monstrous Powerslave—it has recently garnered XC attention with its own epic, a 10-mile, high-elevation shred called Vallelujah. Ever progressive, Nelson has even added a bit of downtown newschool riding—Lefty’s, the city’s newest trail and first machine-built jump line, just a short pedal from town.

The Slocan area is even farther north, home to the 500-person New Denver as well as possibly the most talked-about operation in mountain biking: Retallack Lodge. Famous for its winter cat skiing, Retallack has recently started offering shuttle and heli assisted riding, and their quickly growing network of trails is the embodiment of the newschool freeride style...no pedaling required.

The steep, techy descents and twisting skinnies from the films generated all sorts of interest, and soon riders were showing up in droves.

However, the newest and most unique location in the West Kootenays is Revelstoke, a small mountain town just over Rogers Pass. High-alpine singletrack like Frisby Ridge and Keystone Basin are a type of riding offered nowhere else in the area—and possibly even British Columbia. Along with the impressive efforts of local trail builders, the tiny railroad town has redrawn the boundaries of the West Kootenay bike scene.

“Revelstoke has definitely come on strong in the last few years,” says Holt, “It’s really helped to spread people all over the West Kootenays. A few years ago everyone was just coming to Nelson and Rossland—now it’s all the way up through Slocan to Revelstoke.”

While all that remains of the mining origins of the West Kootenays are trailside relics and ruins, the legacy of pioneering and exploration continues in the trail builders and riders of today. And while the promise of discovering an easy fortune may have faded, the West Kootenays now draws another type of miner, these ones seeking a two-wheeled wealth in brown gold.

“I think it’s a series of things that makes it so incredible” Holt says. “It’s one of those spots that’s not that easy to get to, so when you pull around the corner that first time—whether you’re coming into Rossland or Nelson or Revelstoke—it’s immediately this beautiful setting, massive peaks and lush forest and perfect dirt. It suits mountain biking perfectly.”