Analog Anarchy The Calculated Chaos of Stephen Wilde's Photography

Words by Brice Minnigh | Photos by Stephen Wilde

In today’s fail-safe world of digital photography, few things feel risky—and even fewer things feel truly dangerous.

With LCD screens constantly flashing back images for immediate review, it’s easy to repeat shots until the desired result is achieved. Photographers no longer need to rely on their intuition, on that proverbial “sixth sense,” to know when they’ve captured the perfect moment.

Gone are the days of rushing to the darkroom to develop freshly exposed film in anxious anticipation of what would appear on the other side. The stress of shielding lead-lined film containers filled with the irreplaceable gems of a once-in-a-lifetime assignment—and of keeping them from airport X-ray machines at all costs— is mostly a thing of the past.

These days, it’s hard to actually fail, and outcomes can feel predictably routine. Post-processing options are swapped with the click of a mouse, salvaging even poorly executed shots by readjusting exposure levels. The breathless seconds of pulling negatives from chemical baths are distant memories for most.

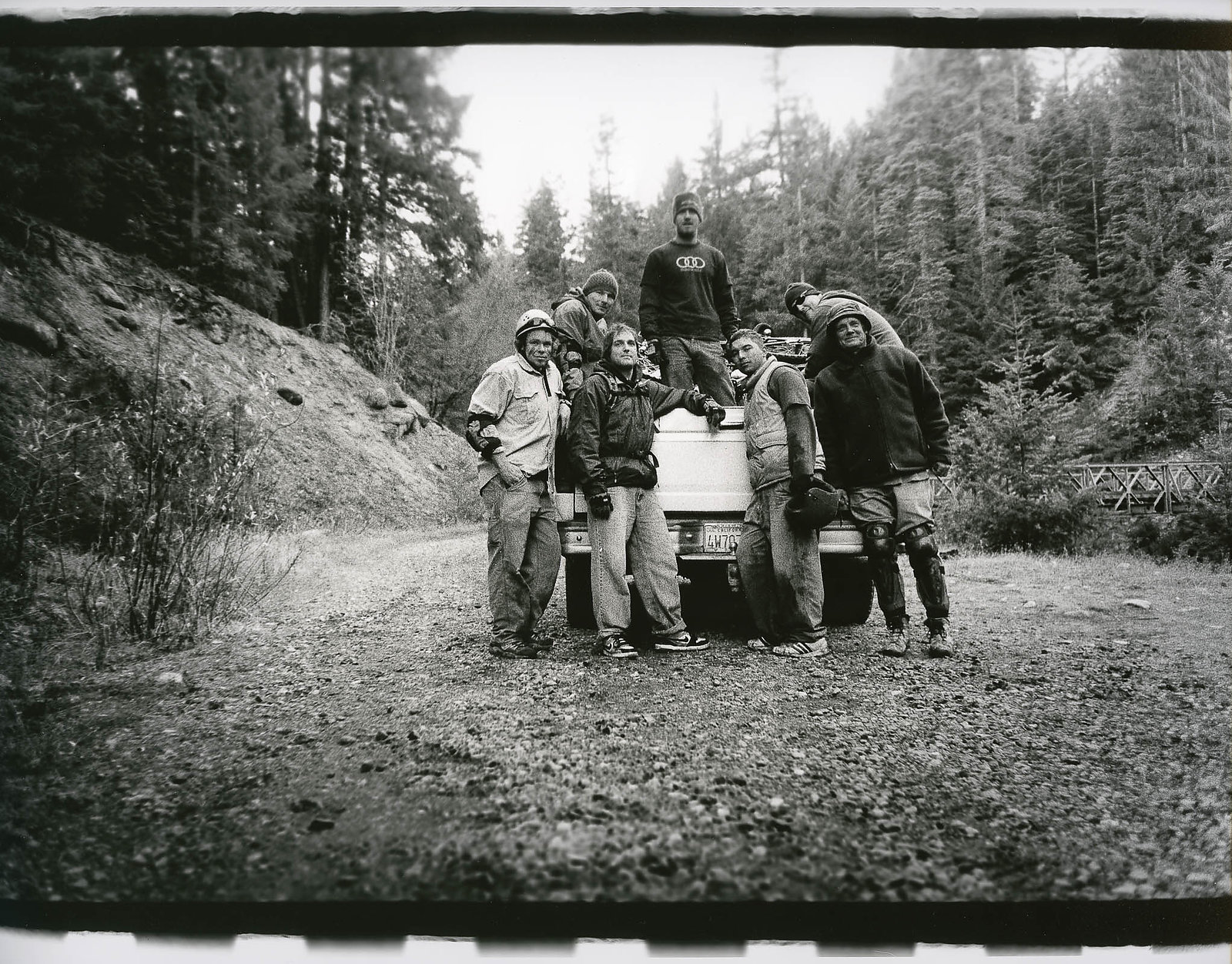

This was simply not the case for the forefathers of mountain bike photography. Back when it was possible to fail—when hard-fought assignments were one ill-chosen f-stop from inadequacy—lensmen such as Tom Moran, Bob Allen, John Gibson, David Epperson and eventually Sterling Lorence were putting their reputations on the line with each and every shoot. But few, if any, were as consistently fearless as Canadian Stephen Wilde, whose inimitable eye and appetite for radical experimentation put him in a league of his own.

Raised in Vanderhoof, British Columbia, Wilde studied photography at what was formerly known as the Alberta College of Art and Design in Calgary, where he began developing a fine-arts approach to his work. He further honed his skills during a coveted internship with American portrait photographer Annie Leibovitz in 1997, and the experience strongly affirmed his proclivity for adventurousness behind the lens. Wilde’s technical prowess and audacious instincts, paired with his deep love for mountain bike culture, enabled him to document nuances of the sport in a boldly inventive manner.

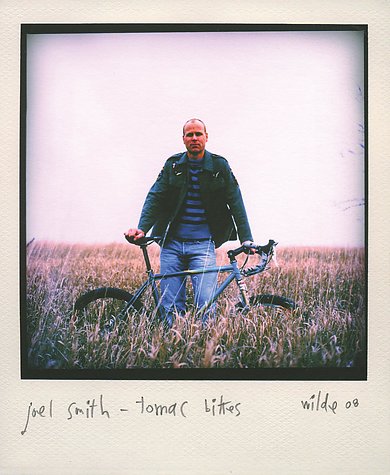

“I would put Stephen way in that progressive category, ahead of the rest of us, always and forever,” Lorence says. “He had a next-level talent of expressing his subjects, not only in the way he took a shot, but also in the way he presented it. When you look back through the archives, he was using the most abstract ways of presenting photos.”

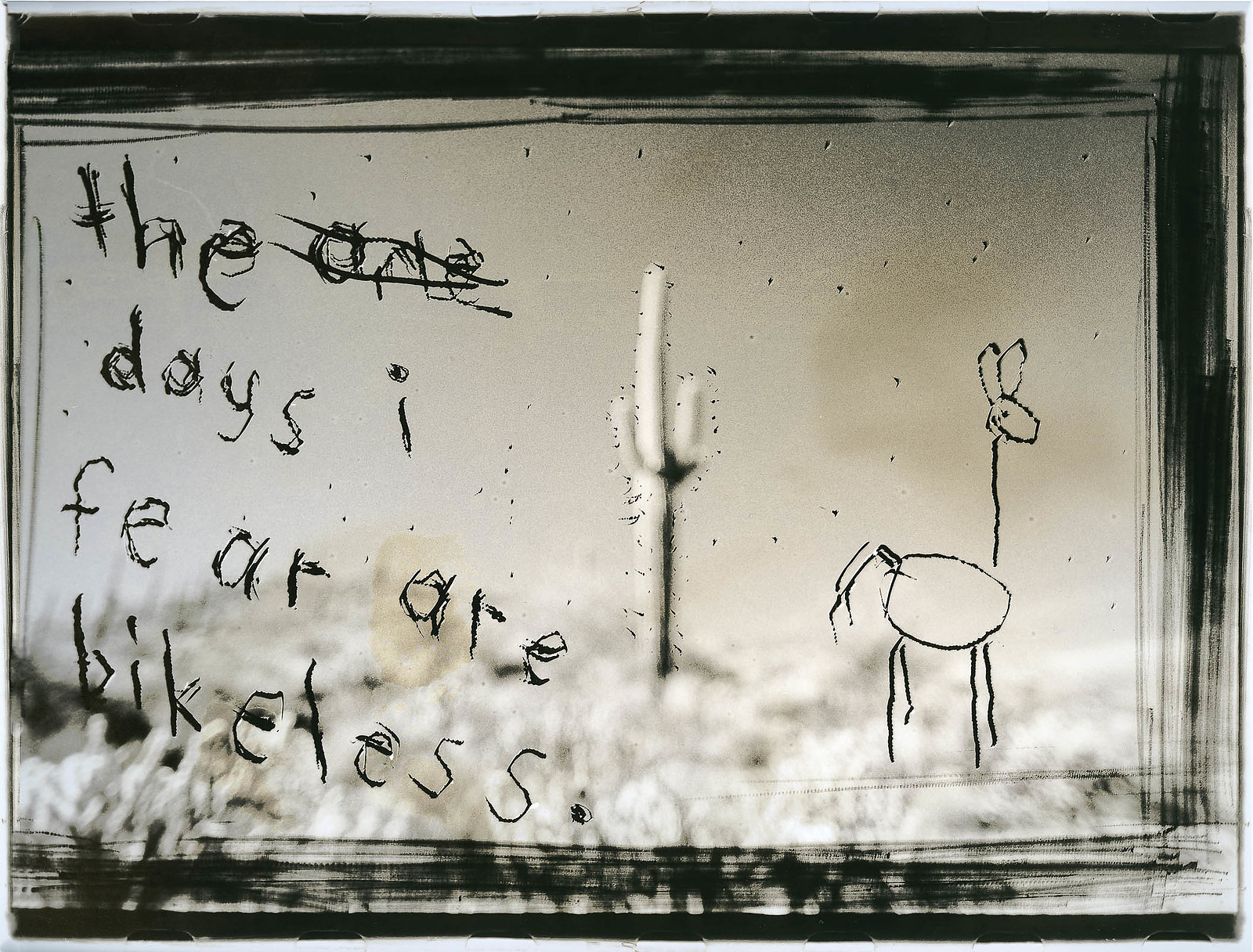

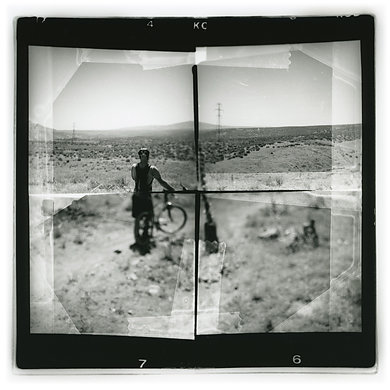

Wilde’s process has always been highly conceptual, and his creative vision typically veers toward the unusual and the unexpected.

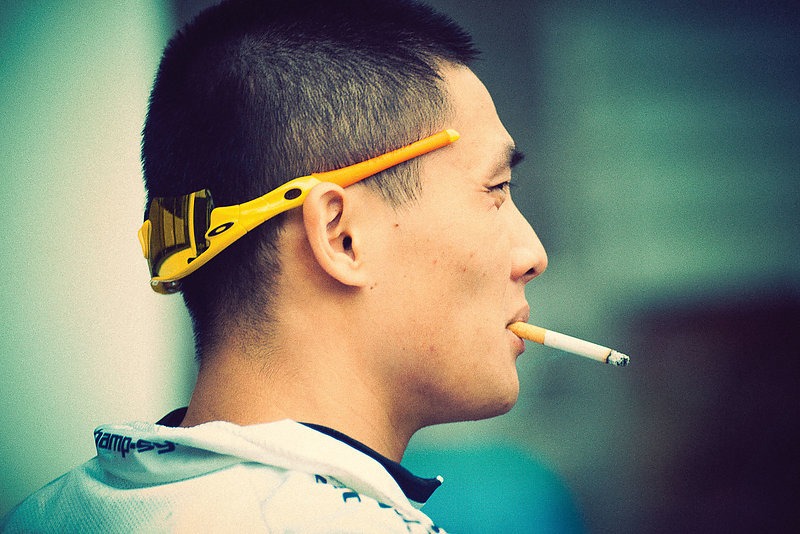

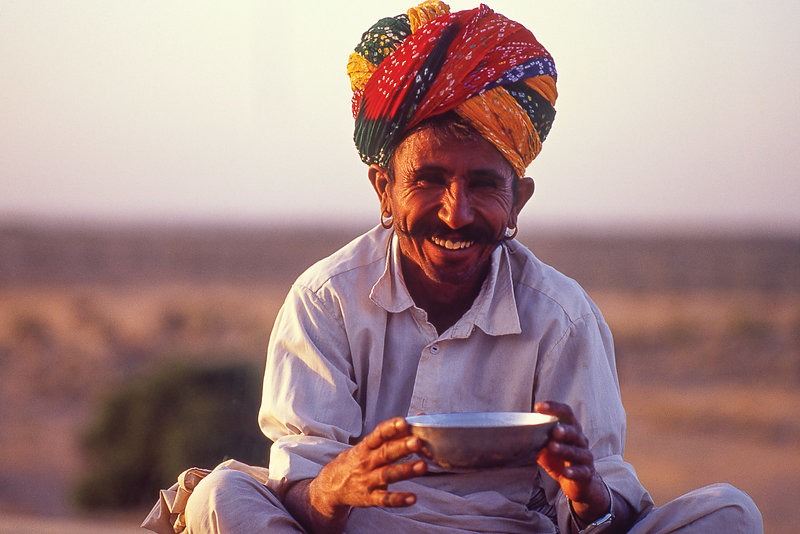

“Stephen’s inspiration, what caught his eye, was different than most,” Lorence says. “He was inspired by the culture and the characters of the sport. We’re all such a bunch of kooks, and he had such a good eye for the wacky things and all those moments that don’t happen on the trail. It was Stephen who inspired us to look beyond that obvious trail shot.”

While Wilde is characterized by some as a “photographer’s photographer,” Lorence believes his talents transcend that description, referring to him as “more of a ‘fine-arts, painter’s photographer.’”

“He was always thinking in terms of colors and tones and moods,” Lorence says. “And he would nail the moods he was feeling through the colors he was documenting. He was almost like a painter, and he had mastered all those different types of paintbrushes.”

Exposing negatives to shroud his subjects in the moods he was feeling was only the beginning for Wilde. Next came the darkroom, where his penchant for perilous experimentation—a potentially disastrous risk in the pre-digital era—would be satiated. Here, all sorts of alternative development methods were in the offing: Cross-processing, bleaching/ selenium toning and even the bending of negatives would be employed to realize his desired effects.

“It was risky for sure,” Lorence says. “It was at the beginning of my years as a photographer, and what he was doing was so artistically unique in mountain bike photography. I remember thinking it was intimidating that the rest of us would have to compete against something like that. But I was also excited that he was bringing such a diverse and artistic spread to mountain biking.”

Though the analog era has long been eclipsed by mainstream digital photography, the ethos of Wilde’s early work still has resonance, as evidenced by the widespread use of digital processing mechanisms designed to instill photos with a retrospective look.

“Nowadays, photographers are searching the internet for plug-ins or scouring their Lightroom for presets to give their photos an

alternative look that is merely emulating the manipulation of real film stocks that Stephen was doing organically,” Lorence says. “But they don’t have to risk it all like he did.”