The Architect - Dave Weagle's Suspension Revolution

Mountain bikers should thank their lucky stars that suspension guru Dave Weagle didn’t have a bigger apartment.

Weagle grew up in central Massachusetts, an all-around athlete who played hockey, basketball and baseball, and rode motocross. Plenty of motocross. In the mid-1990s, after high school, he moved east to Boston, and the Wentworth Institute of Technology, to pursue a mechanical engineering degree and his dreams of working for a Formula 1 racing team.

“I had basically tailored my schooling toward that,” Weagle says. “But when it came time to pull the trigger, I had met my now-wife, and decided I really didn’t want to move to the UK to pursue F1 racing. I had done my due diligence, and it really didn’t seem like the right move for me.”

Instead, in 1998 the newly minted graduate went to work for Draper Laboratory, a contractor for the United States Department of Defense. Living in the Boston area, Weagle still had the itch for some throttle twisting.

But his apartment had space limitations. “I would have never, ever, ever bought a mountain bike,” he says. “I would have continued to ride motocross. But I couldn’t fit a motocross bike in my apartment.

“All of my buddies had mountain bikes, and they were having fun, riding in Lynn Woods, so I took a shot. I went out with them a couple of times, and that was pretty much it.”

Weagle’s inquisitive, analytical mind shifted gears—literally.

“As I got into mountain biking a little further, I started looking at these bikes and saying ‘What the heck is going on with these things?’” he says. “I had the suspension background, I had the athletic background, and I really melded the two together. And started thinking about what the heck is this thing actually doing?

“It’s crazy, but nobody had actually published any kind of technical analysis of how chain-driven wheel suspension actually functions. It’s insane to think that in the 100 years of motorcycles, no one had actually taken the time to do it. But if you think about motorcycles, you hit the gas, and it really doesn’t matter.”

Motorcycles simply evolved. “They would just move things around until things worked, and it was all good,” Weagle says. Being human-powered, mountain bikes were a different animal—or, more accurately, machine—altogether.

Weagle says he had an idea of what he was feeling while riding, but wanted to quantify those sensations. One, for example, is what he calls the “language of feel,” which he wanted to define mathematically. It was a sensation he believes first developed in both his early riding and his activities outside of biking.

“I’ve always attributed the fact that I have a propensity for feel, or maybe a finer-tuned sense than most people, to the fact that my main sport growing up was playing hockey,” Weagle says. “I was on blades my whole life. I don’t know if there’s any truth to that, but that’s what I’ve always imagined.”

Weagle built a language for the math, and soon wrote a paper on how “chain-driven suspension actually reacts to acceleration forces.” Now he just had to decide what to do with it.

Weagle continued to ride, and race, with a distinct preference for downhilling. While he’s learned (reluctantly, he says) to pedal over the years, he still prefers spending his day using another machine—a chairlift—over grinding out long climbs.

“I would have never had success in mountain biking if I wasn’t able to ride the bike, and, at one point, ride at a reasonably high level.”

“I was pretty notorious in the NORBA pits for suspension tuning and helping people sort through their own bikes,” Weagle says. “Suspension tuning back in the day was quite a bit more rudimentary than it is now.”

Weagle specifically targeted the dampers that were popular at the time, which he says “didn’t function all that well. So just making them work at all was really, really important.”

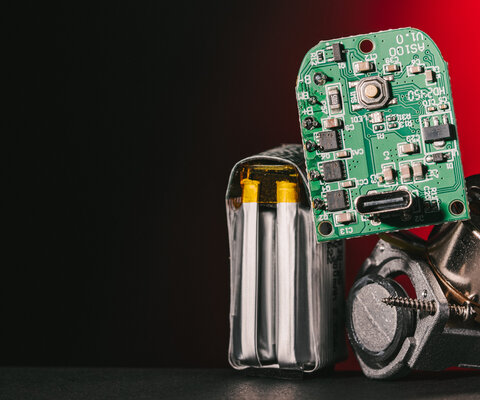

He began tinkering with existing suspension platforms and building his own bikes. Together with some friends, Weagle launched Evil bikes in 1999, followed by e*thirteen drivetrain components in 2002. But his work at NORBA races was also turning heads.

“You had bikes like Intense that were amazing bikes for the time, but they had a lot of adjustments,” he says. “And only a couple of the adjustments were functional in any real way. Understanding how they functioned, why they functioned, what the limitations of the existing dampers were, and helping riders through that, I got myself a reputation in the pits.”

Those experiences and the subsequent reputation he earned led to an offer to develop a product line for Iron Horse, which had started to heavily invest in its mountain bike department. Weagle said he took the suspension methodology he had developed and eventually created a “kind of idealized system that became [the] DW-link.” The title came from his nickname at the time, and was officially coined by a friend.

This groundbreaking suspension design marked a watershed moment in mountain biking. From a pure downhilling perspective, it was a sort of mechanical revolution akin to the Repack pioneers in the 1970s, bombing down Mount Tamalpais in California’s Marin County aboard their “clunkers” and “ballooner” bikes: It defined what was possible, and set the standard for what was to come.

The terminology is a bit intimidating, but the design is centered on the concept that “varying anti-squat can be used to counteract the negative effects of load transfer on a bicycle suspension,” Weagle says. “I didn’t invent anti-squat. That’s just a known phenomenon in vehicle suspension. Your car has that. Your city bus has that.”

Essentially, “anti-squat” helps suppress natural weight transfer under acceleration, which helps the rider to keep the bike’s wheels in contact with the ground while providing enough suspension to keep the rider’s backside in the saddle, instead of acting like a catapult.

Like many landmark inventions, the DW-link and Weagle’s work with those temperamental dampers has withstood the test of time.

“If you go back and look at pre-2003 bikes, and post-2003, the direction [of suspension design] has moved a lot closer to what I was doing early on and farther away from any other design,” he says. “There’s really no other design. Every design has moved this way.

“That’s made bikes better for everybody. It’s made suspension more compliant.”

Weagle left Draper Labs in 2003. “Eventually, I saw a gun mounted on a robot that I had designed, and decided that perhaps military engineering wasn’t for me,” he says.

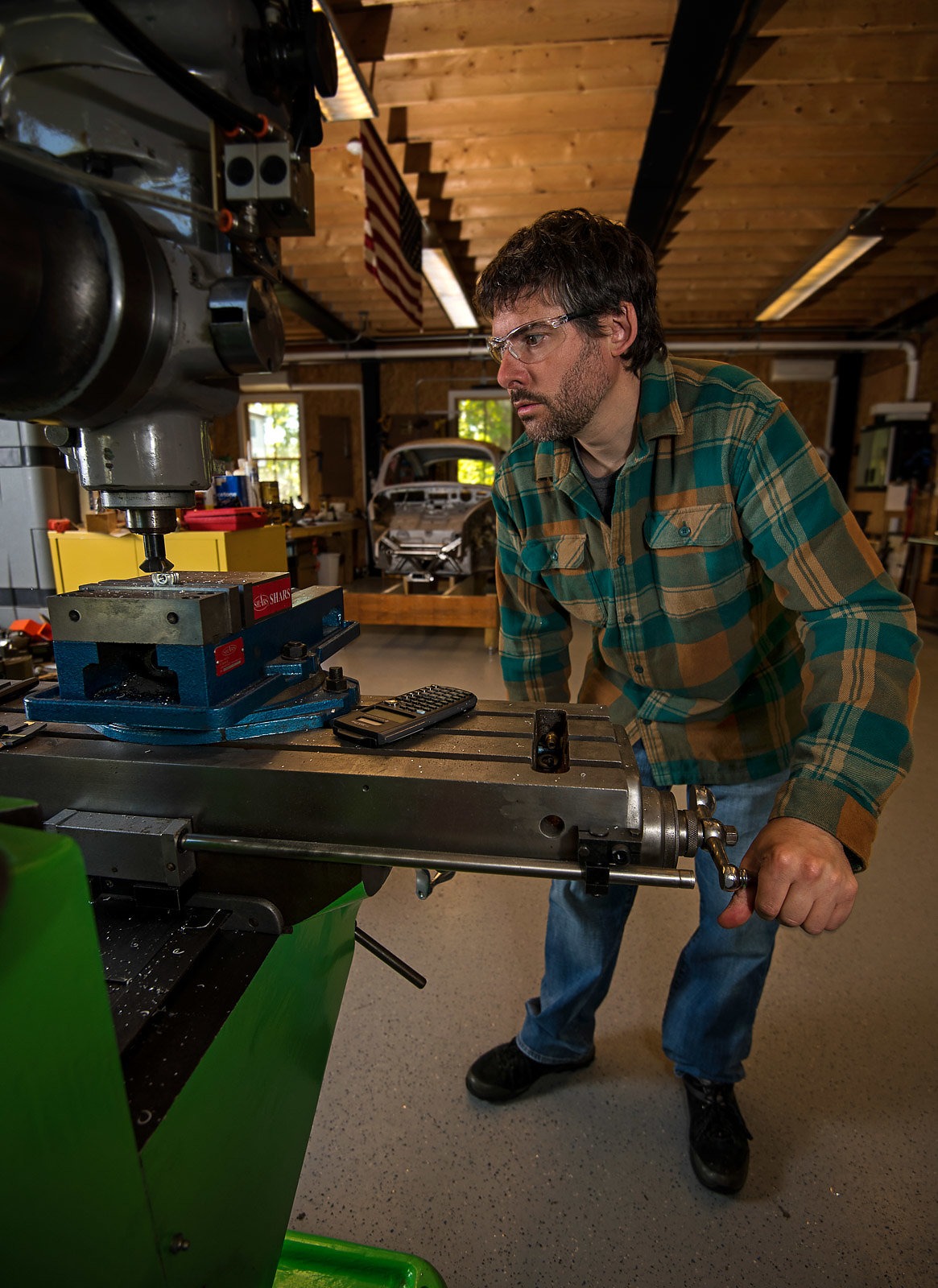

Free to do what he wanted, he then committed himself full time to bike and bike suspension design. And Weagle has never once sat on his laurels.

“In terms of suspension design, where we were 10 years ago, the designs that I put out there, that I worked on, were definitely [utility] knife-type products,” Weagle says. “You could use them for anything. I would say today, in 2016, nearly every single product that is sold has gone in the direction of what I was doing in 2005 and 2006.”

In the past 16 years, he has created a number of suspension designs, led by several iterations of the DW-link (on Iron Horse, Pivot, Ibis and Turner bikes), the DELTA system found on Evil bikes, and the Split Pivot (on Devinci and Salsa bikes). The goal, Weagle says, has always been to help the bike vanish underneath the rider.

“For me, [suspension design] is more about the people,” he says. “My biggest goal, my biggest achievement, is when the product really disappears. It’s just gone. It’s totally transparent.”

Asked what his specific goals are when designing a bike or a suspension system, Weagle says, “However the rider really wants it.”

“I can’t necessarily prescribe that, unless we’re talking about a race bike for a specific athlete, in which case that specific athlete has areas where they’re better and some areas where they’re struggling, so we’ll work specifically with that,” he says. “A downhill bike is a downhill bike, and a cross-country bike is a cross-country bike, just from a pure geometry standpoint, and a suspension travel standpoint.

“There are divisions there, but, by and large, trail bikes today, it’s really about preference,” Weagle says. “You want to ride a longer travel bike, that’s fine. You want to ride a shorter travel bike, that’s fine too. It’s really nothing wrong with either.”

That’s why Weagle is comfortable working with numerous clients, since every bike manufacturer has a slightly different type of ride in mind.

“My goal when consulting partners is to help them build their best possible product,” he says. “Some lines, like the Evil line, I get to do from the ground up. I get to choose the geometry, I get to choose what the product line looks like, I can choose the suspension. I do everything, essentially. Obviously, there are other people working on the project, but I’m the architect of the line.”

Regardless of the company he’s working for, “my job is to coach them on geometry and do all the suspension design for them,” Weagle says.

He also emphasizes that it’s important to respect the specific vision of every company he consults with, and does his best to meet those ideals, not his own. “My goal, from a field standpoint, is to understand who the people behind the companies are, how to make that bike fit with who they are,” he says.

“An Ibis and a Pivot do not ride the same,” Weagle says. “The guys behind the companies are different people, and I think a little bit of division is nice.”

Today, Weagle has set up shop in Martha’s Vineyard, a well-known tourist retreat just off the southern arm of Massachusetts’ Cape Cod where he shares a home with his wife, Linley. The island will never be considered a mountain biking mecca, much like Moab or British Columbia’s North Shore. But that doesn’t bother him.

“My wife grew up here, and that’s where we got married,” he says. “And I like being married. So I’m on Martha’s Vineyard.”

The home office doesn’t hinder his vision. A far cry from that original, cramped apartment, the Weagle workshop is sort of a museum, with more than two-dozen bikes and frames hanging from the walls. Asked if he has a favorite design, Weagle replies without hesitation: “The next one.”

“I’m trying to live more in the present,” he says. “I’ve always enjoyed riding the bikes of the time, or the ones slightly ahead of their time.

“Still, I never really choose favorites. There’s always something better. By the time somebody sees something that I’ve worked on, I’ve already dissected it and I’m completely sick of it. I’ve been looking at it for two-and-a-half years, and probably just done with it.”

However, Weagle is guarded when it comes to future projects, regularly answering with a flat “Can’t talk about it” when asked. That’s understandable, given how many of his designs, from suspension systems to thermoplastic bash guards, have been “borrowed” by other manufacturers over the years.

“If I had a nickel for everyone who told me I was a complete dumbass for trying to build a plastic bash guard, I’d be retired,” he says. “But you can’t buy a metal bash guard anymore.”

Weagle’s work continues to fascinate and invigorate him, especially with the advent and popularization of 29- and 27.5-inch wheels, which offer new dynamics and new challenges. And his continued involvement in the industry, again, is a blessing for mountain bikers everywhere.

“What really excites me are the mechanical problems,” he says. “That’s what I really enjoy—solving difficult challenges. That’s what drives me.”

Weagle readily admits his attitude toward mountain biking has undergone a 180-degree change since he begrudgingly saddled up along with his buddies on the technical trails of Lynn Woods on Boston’s North Shore two decades ago.

“I love the fact that I can work in mountain biking. I love the fact that my work makes people’s lives better, makes people happier,” Weagle says. “People go through their lives dealing with some crappy job, or whatever. Everyone’s got something going on. We all have things personally, or professionally, making us crazy.

“I know that if I go out on my bike, that stuff tends to disappear,” he says. “I’ve heard that time and time again from other riders. Getting out on the trails is like their church.”