Blowing Hot Air Flat Tires and Cheap Electronics

Words by Cy Whitling | Photos by Anthony Smith

The flat tire was simple enough to fix—a small sidewall tear that we quickly plugged with a bacon strip and then took turns reinflating. While our group of three swapped shifts on the mini pump, we discussed a recent surge in sponsored social media posts hawking affordable electronic tire inflators.

The videos were compelling, maybe too compelling: Happy influencer-types quickly inflating tires with vape-shaped objects before flashing cheesy smiles at the camera.

“Your tire pumps in seconds and ready to roll!” one rider exclaims.

I’m a skeptical person. I’m quick to jump to judgement of perceived scams. My friend Finn Hopper was less pessimistic, more informed about electronics, and argued that maybe these pumps had merit. My partner, whose flat tire prompted the conversation, withheld judgement.

When we got home I bought the most-recommended electric mini pump I could find, the Airbank Mini Bike Pump Pocket SE. It was on sale for $24. Now, it costs $39. That’s significantly cheaper than my current favorite pump, the Wolf Tooth Components EnCase 40cc ($64.95). Too good to be true, right?

Since my initial brush with the Airbank, similar electronic mini pumps have hit their stride in mainstream mountain bike media. They’re becoming more common to see on trail, while remaining inescapable on the internet. The beginning of 2025 was notable for it was the point in time in which electric mini pumps went mainstream—no longer the domain of only terminally-online gear nerds. So how does the Airbank work? And, more importantly, what are the tradeoffs we make as riders and consumers when we chase electronic convenience in our gadgets?

I was quite skeptical of the Airbank’s ability to consistently pump up mountain bike tires. Its marketing copy felt out of touch and the product photos all looked a little fake. So, I ran a series of tests. First, I fully charged the Airbank (it takes about 24 minutes to charge from an empty battery). Then I used it to inflate a 29x2.4-inch Schwalbe Tacky Chan from empty to 25 PSI and timed each inflation. Round 1: 1 minute, 30 seconds. Round 2: 1:36. Round 3: 1:48. Round 4: 13 seconds before it died, with the tire at 8 PSI.

For context, in ideal conditions, at max effort, I got the same tire to 25 PSI with my Wolf Tooth pump in 3:08. That left me absolutely gassed so, in real life, I’d say closer to ten minutes with the mini pump.

Next, I recorded the Airbank’s sound level. Phone-based decibel (dB) meters are notoriously inaccurate, but mine read a peak level of 79 dB, while the same meter read the peak of my panting and swearing while inflating the tire manually at 81 dB. The Airbank is loud, but not absurdly so.

I used the Airbank to seat the bead on the same tire, and it did so, no problem. My mini pump did not.

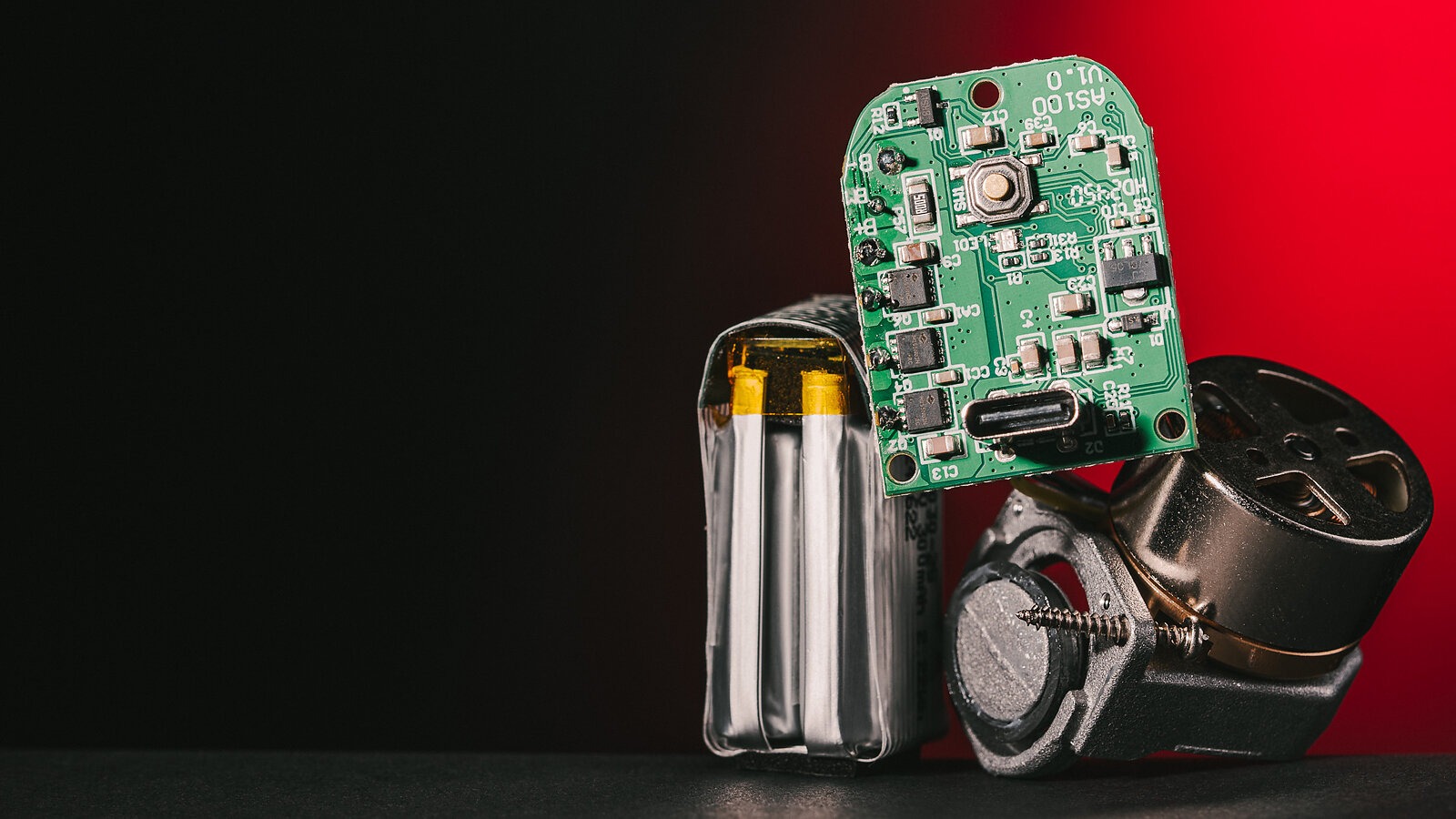

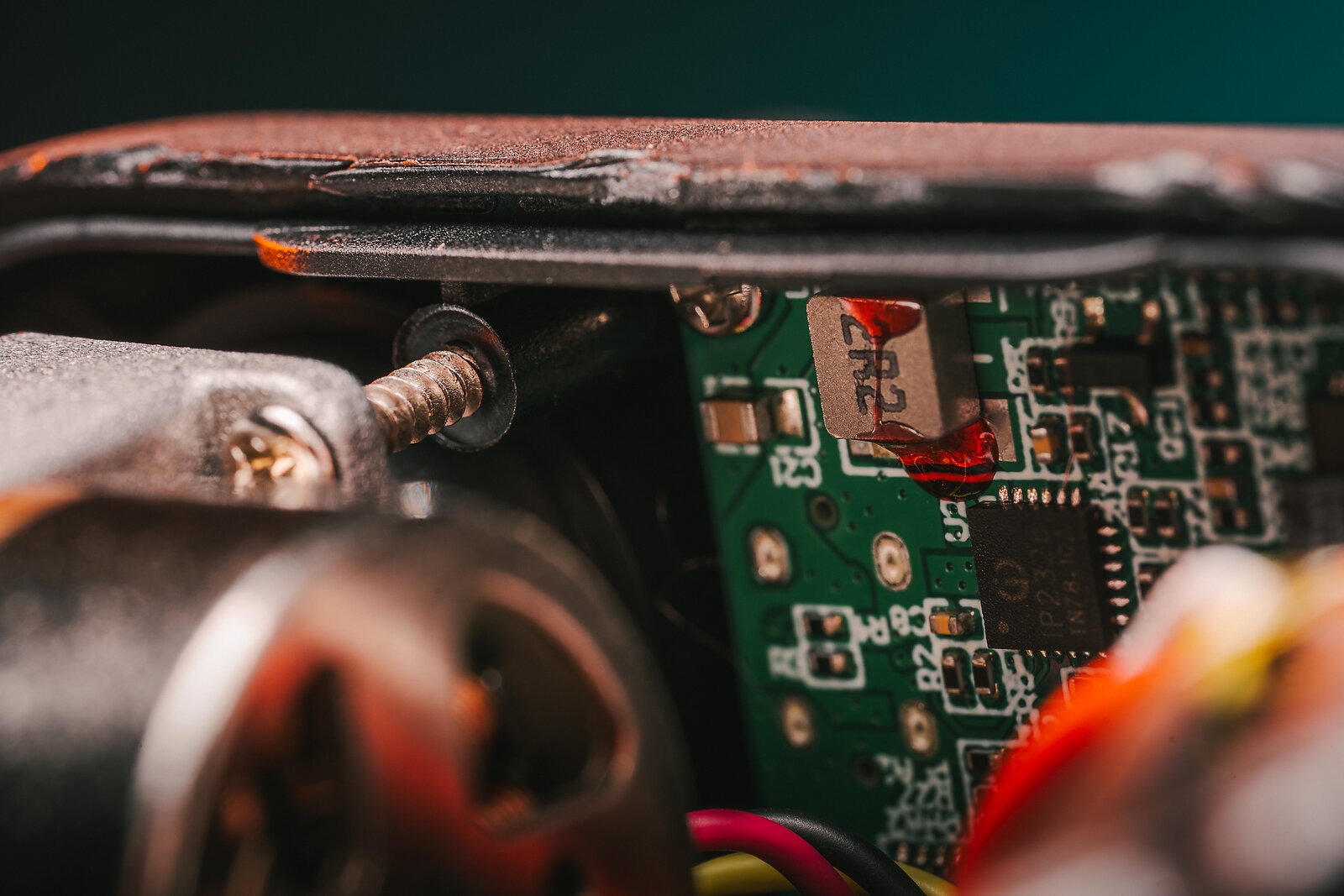

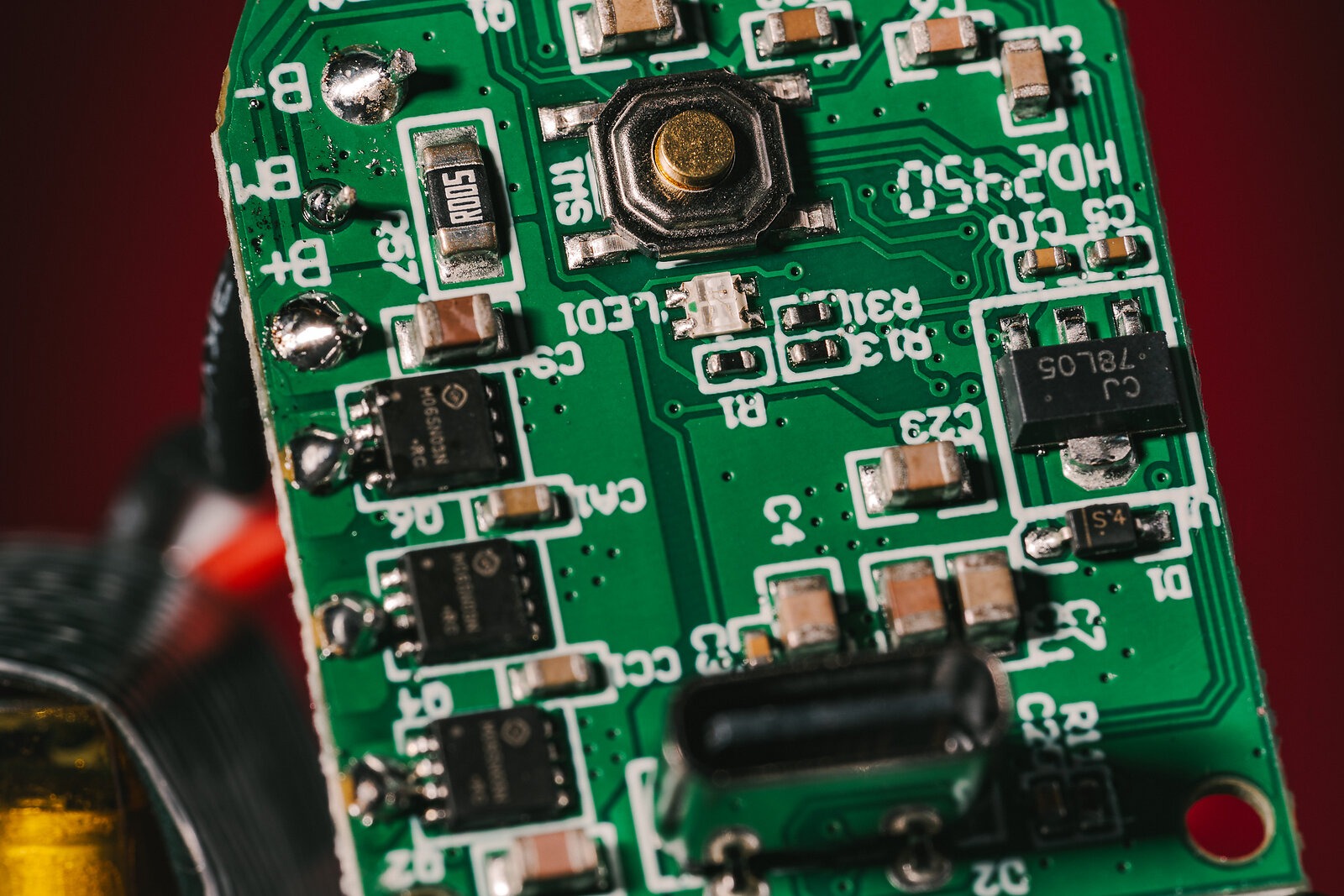

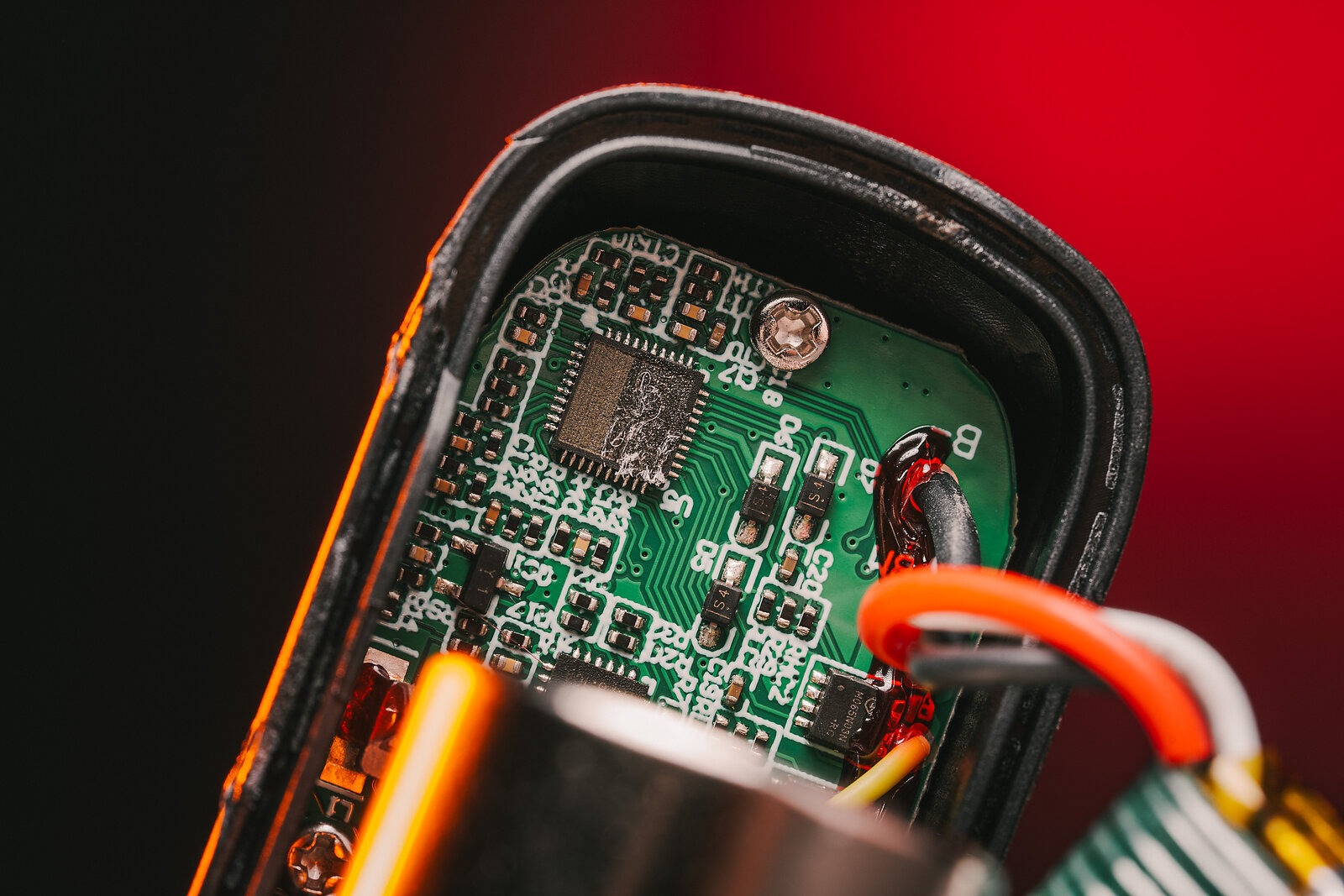

With all that out of the way, it was time to crack open the Airbank. Finn builds and flies nano-scale racing drones, so he had the tools and knowledge to dive into the device. Inside we found a small 2.22Wh 2S Li-Po battery pack with a nominal operating range of 6.4 to 8.4V, along with a circuit board, and a small drone-style motor running a forged piston and very simple valve. The build quality was neither exceptionally bad nor impressively good, and nothing really stood out in terms of the electronics. I’ve had several quick glimpses inside other electric mini pumps, at a range of prices, and all of them seem to share this same basic architecture.

Finn ran a few tests and did some rough math to get an idea of the load that the system put on the battery, and then we called in our ringer.

Tom “Danger” Place is a co-owner, lighting engineer, tester, and customer service manager at Outbound Lighting. He’s a very well-educated and informed nerd who loves taking electronics apart and figuring out how to make them better. He's the kind of guy who can disassemble a hotel TV to gather emergency parts, or direct a full camera rebuild over a video call. I gave Tom the info we’d gathered about the Airbank, and he took it apart again to confirm and do some tests of his own.

Li-Po or lithium-polymer batteries, like the one found in the Airbank and the ones found in your phone, have a reputation for occasionally catching on fire. There are a few reasons for that—stories about electronics catching on fire tend to make an outsized impact in the media landscape and poorly-designed batteries, along with the electronics that overload them, are often present in very cheap products. Could the Airbank be a liability? And is it possible to make an informed decision about the safety of cheap electronic products before hitting “Add To Cart”?

“If it’s a product that looks like an obviously cheap Temu-style product that’s just been rebranded, try to find it on Temu—usually you can—to help inform your decision,” Tom said, mentioning a Chinese e-commerce company known for its bottom-of-the-barrel pricing. “If the company is some nonsense named brand you’ve never heard of that only sells stuff with AI-shitty photoshopped images in Amazon listings, then maybe don’t trust it. If it’s a legitimate brand and a unique product, they’re probably highly invested in making products that don’t catch fire for the sake of their brand and liability.”

At first glance, Airbank flirts with that line. The mockups aren’t terrible, but they’re not exactly convincing either. Same goes for the product copy: “Are you tired of encountering tire deflation and carrying heavy bike pump when riding?” it asks. It’s hard to tell what’s a bad translation, and what’s AI generated.

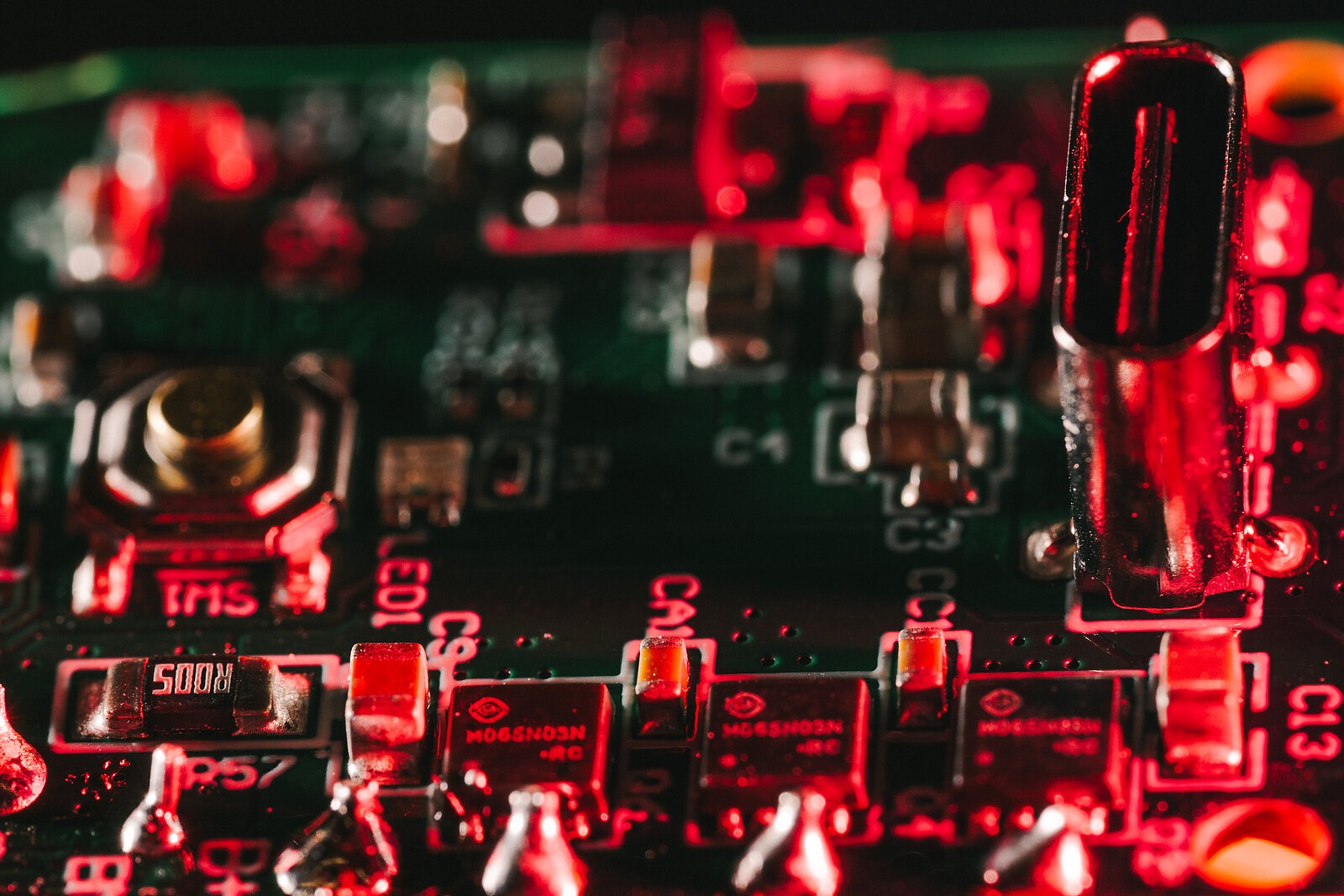

Tom’s testing confirmed that the Airbank is very unlikely to act as a little bomb in a plastic case waiting to ignite. Every battery has a “C-rating”—the measurement of current at which it is charged and discharged. Since this is a 2.22 Wh pack, a charge or discharge current of 2.22 watts would equal 1C. Finn and Tom’s testing found that this device is charging at around 3 to 4C and discharging at about 12C.

In practical terms, the higher the C value, the more strain is being put on the battery, and the more likely bad, fiery things are going to happen. Protection circuits help prevent those fiery things, even at higher C values, but they’re not often present on cheaper products. The Airbank’s discharge C ratings are higher than, say, a vape, but lower than the 30-40C rate remote control applications like a drone would see, and it has several protection measures in place. No red flags here.

The second reason that cheap electronics often fail is standby current or what colloquially is known as “vampire draw.” Thanks to entropy, batteries don’t just stay fully charged forever. And if they’re left fully discharged for long enough, the cells fail and no longer accept a charge. In a product like the Airbank that effectively bricks it. There’s no way to replace the battery. If it dies, it’s done forever. That’s especially concerning in an emergency product like the Airbank. If you don’t flat often, it’ll spend a lot of time in your pack, never getting used, and probably never getting charged.

I’ve run into this issue firsthand with a few products. Li-Po batteries are use-it-or-lose-it, meaning it’s actually much better for the battery if you use it and recharge it every day, like your phone, rather than only checking on it every couple months. This was our biggest concern with the Airbank. However, Tom hooked it up to a digital multimeter, ran some tests, and determined that it had a very low standby draw of 1uA, which means that with a full battery it should hold a charge for about one year.

That low draw, combined with protection circuits and built-in stepdown of power draw as the battery depleted, allayed our fears both of spontaneous ignition and of vampire draw rendering the pump useless. Our fiddling and testing found that from an electronic standpoint, the Airbank was completely adequate.

Though, that didn’t address my other core concern with the Airbank: It doesn’t resemble or have the feature set of something that was designed by and for mountain bikers. Its form factor fits in nicely with the vape and AirPod aesthetic, but it is completely out of place on a bike. It doesn’t fit any of the places I’d typically store a pump, like inside frame storage, next to a water bottle, or below the top tube. The Airbank isn’t alone in this. I have yet to see an electronic mini pump with a form factor that makes sense for mountain bikers. These companies are marketing effectively, but seem less concerned with making a product that functions seamlessly with the modern mountain biker.

The Airbank also does not have any water or dust resistance seals. Instead, it comes with a Ziplock bag to keep it in. Simple, but inelegant. In fact, the air intake is through the USB-C charging port. If you’ve ever had to clean pocket lint out of your phone’s charge port, you know how bad of an idea this is.

Finally, the electronic choices being made with the Airbank display a lack of understanding of what mountain bikers want or need. If electronic pumps are going to gain mainstream acceptance, they must marry the speed and convenience of a CO2 inflator with the reliability of a manual mini pump.

“Electric pumps have a literal ‘easy button’ to inflate your tires which sounds amazing. The downside is that they don't work at all if the battery is dead, and I have no idea how long they last or if you can get replacement parts like seals,” said Dan Dittimer, the co-owner of Wolf Tooth Components. “The [Wolf Tooth] EnCase pumps were designed to be ultra reliable and dependable. Several of us had experiences where the pumps [or] CO2s we were carrying failed us for various reasons which in a few cases resulted in a very long walk back to the trailhead.”

When you need a mini pump, you really need that mini pump to work.

I spoke with design engineer Jack Goodwin, who has a penchant for pushing his bikes and components to their limits, to ask him about whether he’d consider using an electronic mini pump.

“If my pump were to have a battery, that would mean that in order to retain that peace of mind, I’d have to systematically plug the damn thing in after a ride and then equip it back on me for my next ride,” Jack said. “We’ve now gone from out of sight, out of mind to plainly in sight, front of mind. That is a fundamentally different tool.”

Tom and Finn both pointed out that there is no obvious reason that the Airbank doesn’t just use a common 18650 Lithium-Ion cell instead of its Li-Po battery. This would give it around six times the capacity and help allay fears about thermal overload and standby current. Those 18650 cells are found in everything from e-bikes to electric cars and would make it possible to replace only the battery if it went bad instead of tossing the entire product.

I don’t love electronics on mountain bikes, but I can imagine buying an electronic mini pump. However, it wouldn’t look like the Airbank. It would have the form factor of a traditional mini pump, it would have storage for bacon strips or another form of tire plug. It would need a more reliable, replaceable battery, and it would need to be made by a company that understood and cared about mountain biking.

That last point led me to Fumpa, the “inventors of the rechargeable bike pump.” Fumpa makes all its pumps in Australia, offers user-replaceable batteries, and sponsors the Decathlon-AG2R La Mondiale World Tour and Orbea Fox Factory racing teams.

The most similar product in Fumpa’s line to the Airbank is the Nano pump. It’s significantly more expensive than the Airbank at $99, and features an aluminum shell instead of plastic. But Fumpa is invested in and concerned with the post-purchase lifestyle of their products. Byron Walmsley, the founder of Fumpa, explained: “[If] your Fumpa’s battery loses its ability to recharge properly, you can replace it yourself by ordering a refurb kit which includes all the parts, instructions, and materials to extend the life of your Fumpa. This provides a far more responsible (to our customers and our environment) solution than a simple ‘throw it out and buy a new one’ consumer model.”

Walmsley also argues that the Fumpa is better suited to the needs of cyclists than more affordable alternatives. They can achieve higher pressures (120+ PSI) without needing to ramp up and then be placed over the valve stem, and Fumpa offers a full range of adaptors and accessories to fit everything from wheelchairs to track bikes.

While Fumpa doesn’t address my form-factor frustrations with electric mini pumps, the company was responsive to my questions and incredibly helpful. I reached out to its generic support email, and just a few hours later had a response from a real person who understood cycling. The same goes for Wolf Tooth Components and Outbound Lighting.

In reporting this piece, I emailed Airbank several times and have yet to hear anything back. That doesn’t make me optimistic about troubleshooting or continued product support. The company’s investment in the product and my experience seems to end as soon as I click “Purchase.”

It took two clicks to buy that original Airbank, and it appeared on my porch fourteen hours later. Capitalism, in its current stage, has enabled effortless consumption.

“The current crop of electric emergency pumps out there is just making more e-waste without enough real-world benefit to be worth it,” Tom told me.

For years I’ve eschewed CO2 cartridges because they’re fiddly and wasteful. I don’t like only having one shot, and I’m rarely in a situation where saving a few moments with a CO2 cartridge would outweigh the effort of using a simple, trusty hand pump.

E-waste, like an electric mini pump with a clogged intake, shot battery, or a bad circuit board, takes that frustration and raises the stakes. Recycling a used CO2 cartridge is easy. In contrast, when a product like an Airbank reaches the end of its lifespan, it’s most likely going to end up in a landfill, leaching trace amounts of toxic elements into the world—to say nothing of the byproducts made during its production.

“Shit is cheap because it’s cheaply made. I could not sell a bike light for $25, because it costs us considerably more to produce each of our lights, for a lot of very good reasons, including paying good wages with benefits to our staff,” said Tom from Outbound Lighting. “There is a spectrum to all this from gouging to undercutting, but at a certain point I would love to see more consumers recognize the choice that’s in front of them when it comes to a reputable brand selling a product at a fair price for what they get, versus an off brand with no accountability trying to sell the cheapest thing possible to do the job.”

If my Airbank dies, I can click “Buy Now” and have another brand new one at my door tomorrow. I can crouch idly as the device whirs into action and fills my tires at the push of a button. Then I’ll pedal my bike with the substantial assistance of a small battery-operated motor. When I shift, yet more tiny batteries flip the derailleur from gear to gear. I’ll go ride trails with signs made from littered car parts, on ground crisscrossed with abandoned cables from the last time these woods were logged.

There’s an abandoned washing machine in this forest. Its circuit board is exposed, a mess of wires and capacitors framed by ferns. Perhaps I’ll stop and contemplate some sort of greater meaning, a heavy-handed metaphor encouraging me to think twice before I consume. Or, perhaps, I’ll just keeping cruising. Convenience is a hell of a drug.