The Journalist Living Large with Brice Minnigh

Words by Sakeus Bankson

Brice Minnigh has a stamp collection. That’s how he ended up at a marionette show with Muhammad Ali, in the capital of North Korea.

It’s the kind of story that would be a highlight of most people’s lives. For Minnigh, it takes two hours of interviewing before he remembers a press trip he took to the country, while he was working for a government newspaper in Beijing.

“For a while I collected North Korean stamps, which have all this wild propaganda art on them,” Minnigh says. “There was a stamp shop in the hotel where we were staying, and as I walked in I saw Muhammad Ali in the foyer. I admire Muhammad Ali in a big way, and I stopped in my tracks and was like, ‘Champ!’ We talked, and next thing I was sitting next to Muhammad Ali at a North Korean puppet show.”

When you have as many stories as Minnigh, veteran journalist and longtime editor of Bike magazine, it’s not surprising you’ll forget a few.

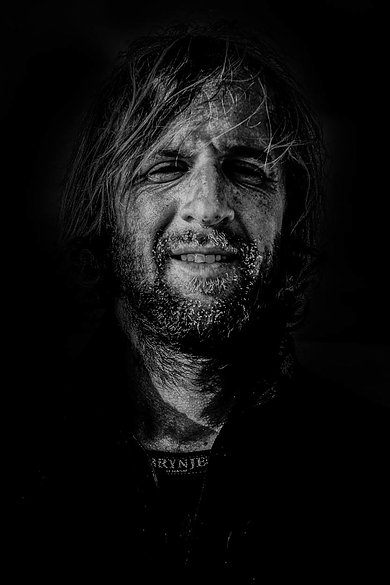

We’re at Minnigh’s home in Encinitas, CA, drinking a beer after a morning surf at a nearby beach break. He enjoys the ocean as much as he enjoys the trails, and the swell has been especially good over the past few weeks. The slight 46-year-old is grizzled, with salt-and-pepper scruff covering his jaw and closely shaved head, and as we talk it occasionally twitches to the side. It seems like a shrug, but is actually a tic he picked up while reporting in southern Russia.

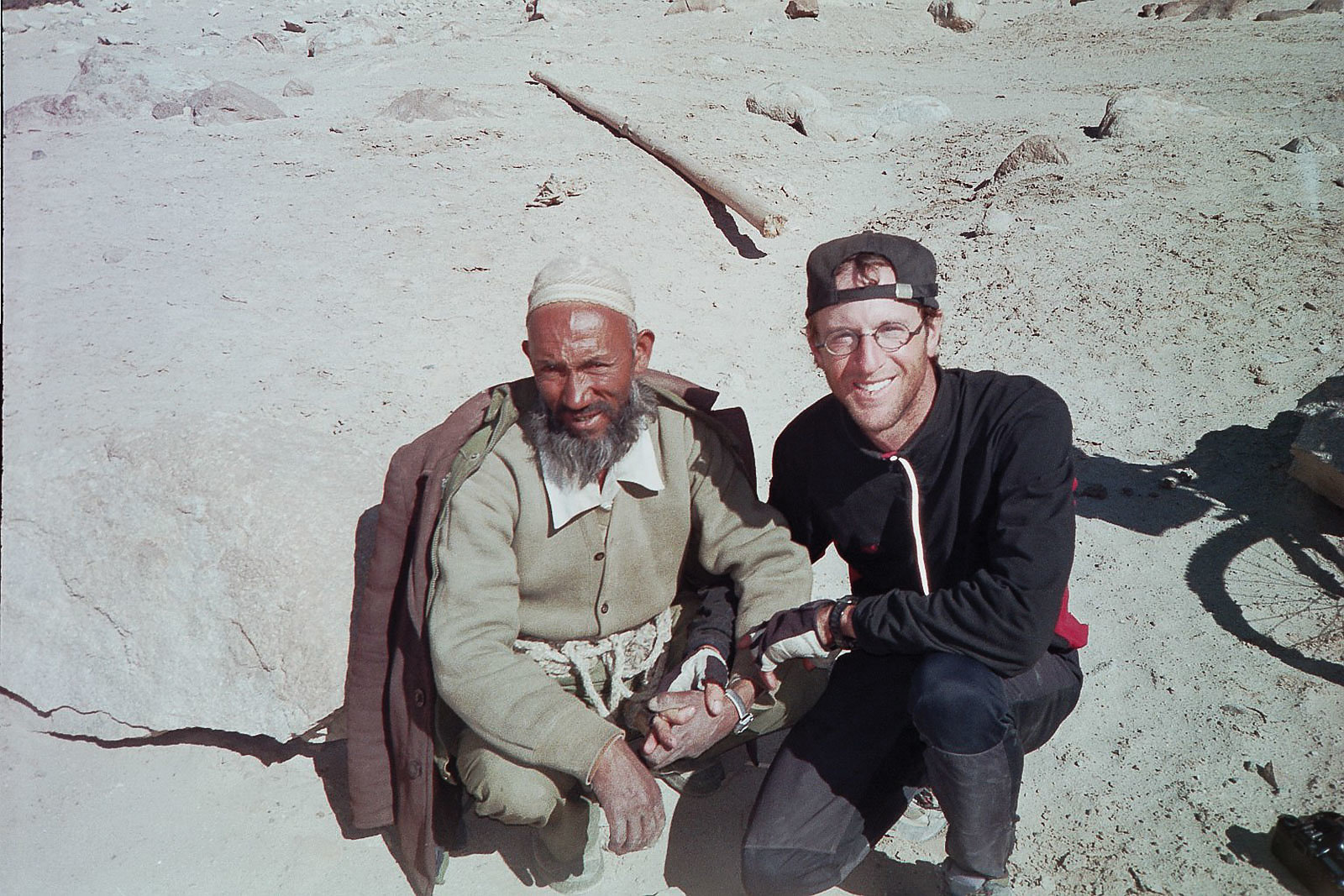

Before we start the meaty part of the interview, he gives me some background on the photos around the room. A bike trip to Taiwan. Peasants in China. Memorable Bike cover shots. One of the three guidebooks he wrote covering Greater China, a part of the world where he lived for more than a decade.

It doesn’t take long before it becomes obvious Minnigh is way overqualified for his current job. And that’s not to rag on Bike. It’s the most prestigious mountain bike mag in the world, and Minnigh is rightfully proud of his time there and the team he’s assembled.

The discrepancy only arises because the rest of his resume belongs to someone working at publications like National Geographic or Time. Minnigh speaks four languages—English, Russian, Mandarin and Cantonese—and before he joined the Bike team, his byline had graced newspapers and magazines across the world.

He’s been to the North Pole, almost died while skiing across Greenland’s ice sheet, oversaw Reuters’ entire Asian debt-reporting division, and biked across China to Pakistan. His passports have almost as many stamps as his North Korean propaganda postage collection.

As he lines out the incredibly convoluted chronology of his life, there is one common thread. A journalist’s job is to tell the story, and Minnigh is pure journalist. Now, after nearly 30 years of reporting, Minnigh’s tale has become an epic story in itself—even if he can’t remember all the parts.

“I didn’t even realize how weird that might sound to people until I was telling a friend years later,” Minnigh says. “The subject came up, and I said, ‘I met Muhammad Ali in North Korea!’ That’s when I realized it probably sounded a little strange. But that’s my fucking life. And it’s hilarious.”

Born outside of Washington D.C. in 1970, Brice’s outdoor wanderings started early. His father, George Jr., was a backcountry specialist park ranger, and his job took Brice, his mother Janet and his brother George to different national parks across the United States. Eventually they landed for good at the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, near Gatlinburg, TN.

Growing up, Minnigh developed a rebellious side. He played soccer in high school, and thanks to his parents’ upbringing, he made friends with many of the minority students—and got into fights as a result. He played drums with his brother in a band, went to punk shows, and skateboarded constantly. But it was while visiting South Carolina that he discovered one of his lifelong passions: surfing. It was here he’d also meet his oldest friend, Roque Elliott. The two surfers both chafed at being landlocked in Gatlinburg, but they made the best of it, skating the drained pools of vacation homes during the off-season.

All the while Minnigh was riding mountain bikes. His first was a fully rigid Bridgestone MB-6 Trailblazer, and he took both the bike and his drumming skills when he moved to Nashville to attend Belmont University as a music major. That, however, didn’t last long.

“I realized they were teaching me to be a human metronome,” he says. “I decided I’d get a real education and major in journalism instead.”

Minnigh had always been an avid reader, and he wasted little time learning the curriculum firsthand. He began an internship at the Tennessean newspaper, which soon turned into a job—and led to him working for the competing paper, the Nashville Banner, a year later. He started with the obituary beat—not the most glamorous position, but one he found invaluable.

“You have to get an obituary right, no mistakes; you can’t run a correction because it’s just not appropriate,” he says. “It’s a good way to get the fundamentals of journalism down.”

After that, Minnigh moved on to general assignments. He remembers finishing an early morning of reporting, and then drinking beer while watching that afternoon’s edition run through the press. Sometimes his byline would be on the front page, an honor that often generated mixed emotions.

“If you have a fatal shooting, it’s going to get on the front page,” he says. “It was kind of twisted. It’s your byline on the front page, but you got there because someone died.”

In the meantime, on the other side of the world, the Soviet Union was beginning to fall apart, and in China, the Tiananmen Square massacre had just happened. As a journalist, Minnigh felt compelled to be a witness and began studying Russian on the side.

“I could feel times were changing in a radical way,” he says, “and I thought, ‘I need to be a foreign correspondent.’”

And so, not long after Minnigh graduated from Belmont in 1992, he was on a plane to Moscow to do just that.

Minnigh arrived in a climate of rapid change. He had taken on an internship with NBC News as part of a study program with Moscow State University, but the job didn’t hold his interest for long. After just half a year, he went full local, beginning a career of freelance work for the Moscow Times and then the Moscow Tribune. It was chaos, and Minnigh thrived.

“It was a really exciting time to be there, with the turmoil and dissolution of all the Soviet states,” he says. “One of the things about journalism is that if you’re willing to go do the gritty things other people don’t want to, you’re going to get a lot of interesting assignments.”

He did. The new jobs carried Minnigh throughout Russia and Eastern Europe, and for two years Minnigh dove fully into the reporting. Surfing, skating and riding bikes fell to the wayside as he followed story after story.

“All I was doing was working,” he says, “and I decided I needed to do something else to get my life back to a more balanced place.”

The “something” turned out to be a ride on the Trans-Siberian Railroad to Beijing in November of 1994. Almost immediately upon arrival, he found a different type of journalism job—“polisher” for the China Daily, an English-language propaganda newspaper for the country’s Communist Party. Basically, Minnigh took poorly translated articles from the Chinese-language People’s Daily and edited them into proper English. Considering the questionable accuracy of many of the articles, Minnigh’s rebellious side couldn’t help but make an occasional appearance.

“We would try to subtly sabotage some stories,” he says. “I won a bet about getting ‘pubic security bureau’ into a headline instead of ‘public security bureau.’ I did it, and while I think it was in the body copy, it won me a case of beer.”

Minnigh worked at the China Daily for nine months, and despite the propaganda angle, found it to be a positive change after some of the heavy subject matter he had covered in Russia. He became fluent in Mandarin. He explored the city. He took photographs. He went to North Korea and met Muhammad Ali. And, most importantly, he started riding his bike. A lot.

“If there was any place in the world that was the land of the bicycle, it was China,” Minnigh says. “We were going everywhere on bikes, and it opened up a whole new world of how to really see the country.”

Along with two expat friends at the paper, he began taking trips outside the city, sometimes putting in 100-mile days. They visited various Ming- and Qing-dynasty tombs and began making missions to different parts of the Great Wall of China.

“We’d take Friday off, and all we’d bring was the gear we were riding in and sometimes these crappy little sleeping bags,” he says. “Then we’d just roll. Ride to a place on a map, stash our bikes at the base of the Wall, and climb up and sleep in these ancient guard towers.”

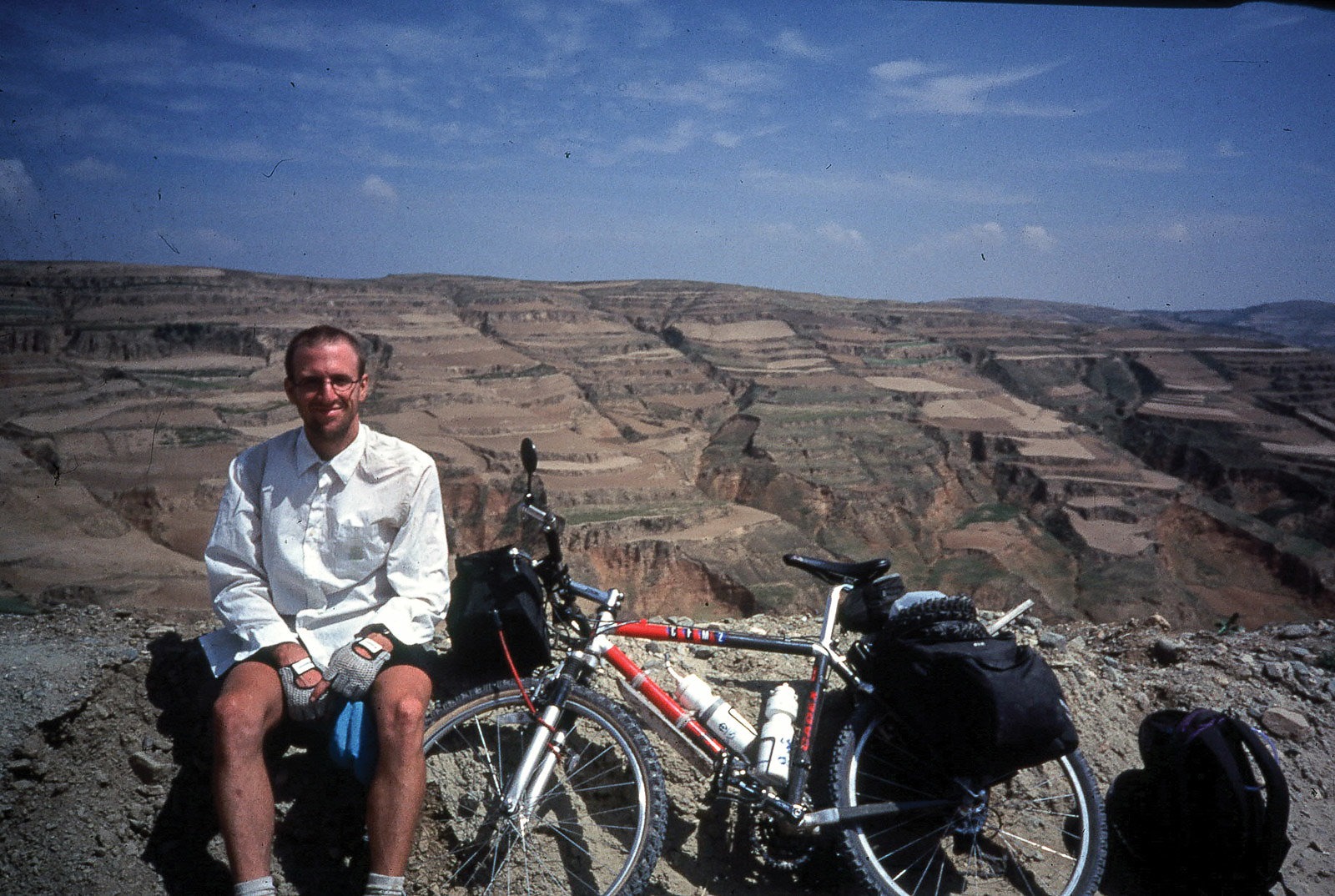

Soon Minnigh and Scott Urban, a Coloradan who also worked at the Daily, envisioned something larger: a trip from Beijing to the border of Pakistan, a 6,500 km journey as the crow flies along the south edge of Inner Mongolia and the Taklamakan Desert. They convinced the Fujianese branch of Giant Bicycles to give them new bikes in exchange for shooting all the images in their Asia calendar, and after working out a story deal with the newspaper, the duo headed out in the fall of 1995.

“For the first 1,800 miles, we were trying to keep the Great Wall in sight, so we could sleep on it and get photographs,” Minnigh says. “It was kind of a daft idea, but sometimes daft ideas are the best ones because they get you in a lot of trouble. And it’s when you get in trouble that you have a real adventure.”

The trip ended up lasting three and a half months, traversing everything from roads to trails to animal paths. Sometimes they stayed in villages, accepting the hospitality of the locals. Other times they found themselves far from anything, sleeping under shower curtains in the rain or biking through bouts of dysentery. There were moments of misery, but the trip was also an epiphany.

“It was gnarly, but it built a lot of character,” he says. “We realized we could still do all this, even though everything was uncomfortable: ‘I’m cold, I’m hungry, I’m sick, but look where I am! I’m on my bike feeling free and living large.’ And I was just hooked. I knew for the rest of my life I was going to be taking big adventures on my bike.”

Following the next few years of Minnigh’s life is far more difficult—even he has trouble remembering the exact timeline. Having finished the China expedition, in 1996 Minnigh based himself out of Vilnius, Lithuania, where he conducted research paid for by a Fulbright grant that saw him traveling back and forth between assignments in the Baltic states and different parts of Russia.

But by the end of the year, China was again calling. Great Britain was scheduled to give Hong Kong back to China in 1997, and—ever the political junkie—Minnigh wanted to be there during the handover. So after returning to the United States for a few weeks to visit his family, at the end of 1996, Minnigh left Lithuania and made the move to Hong Kong. After a quick succession of freelance gigs, Minnigh got his first job in financial journalism for a publication called the International Financing Review. Three years in, he had developed an extensive network of contacts and earned a name for himself. But, in keeping with tradition, by that time he was ready for another daft idea.

In 2000, Minnigh and Urban set out once again, this time on a big horseshoe journey across Northwest China and throughout Tibet. As with their previous trip, the physical demands of the journey were daunting, but the most dangerous difficulties turned out to be the legal kind. Most of the territory they were to cover was closed to outsiders without travel permits—which the two did not have. The result was dozens of arrests.

“We spoke Chinese, were on bikes, and would be accused of being spies,” he says. “So the public security bureau would escort us back east, and then we’d have to ride back the same way, through the goddamn village in the middle of the night.”

That expedition also ended up being three and a half months, by the end of which Minnigh had lost 30 pounds. His adventure bug was satiated, but he was out of work, so he returned to Hong Kong in search of a job and found one in the financial sector he had previously covered—but this time as the executive director of a bank-lobbying group called the Asia-Pacific Loan Market Association. It was a change of pace for Minnigh, and one he didn’t like.

“It was the first time I wasn’t a journalist,” he says, “and after nine months I didn’t feel good about myself. I didn’t believe in what I was doing, and after about a year I left.”

At the same time, Reuters was purchasing a media outlet called Basis Point and needed someone to lead the debt-reporting division. Minnigh’s previous experience made him the perfect candidate, and suddenly he was covering the same banks he’d represented just months before. The job was a hefty one; Minnigh had more than a dozen journalists reporting directly to him, and he was responsible for the accuracy of the reporting of hundreds more.

But by the end of 2003, he was itching for another adventure. In April of 2004, Minnigh took what he calls an “unapproved sabbatical,” and left with Steven Wright, David Jessop and Alexander Moore for a 30-day North Pole expedition. It was a sufferfest, but successful. Reuters even let him keep his job.

Still, following what had now become a lifelong trend, Minnigh found he no longer wanted the position. He left Reuters in December of 2004 to spend the next year freelancing in Hong Kong, before linking back up with Scott Urban for another three-and-a-half-month bike trip. This time it was through Chile, Argentina and Bolivia, and when he returned he had a different ambition: to write a first-edition guidebook about Taiwan for Rough Guides.

Minnigh had spent time in the country during his financial reporting days, and he knew the potential offered by the mountainous terrain, the incredible surf, and the trails snaking through the substantial national parks. He spent a year photographing and researching what would become a 600-page book, information that would be useful on future trips for Bike.

And yet, even as he saw more of what Asia had to offer, his attention was slowly turning west. In 2006, he and a friend named Steve Coward had the chance to ride the Cape Epic, a burly, eight-day stage race in South Africa. Back in Hong Kong, Coward and Minnigh began training hard, but the pollution was so bad they had to wear medical masks during rides. Then he received a phone call from Roque Elliott, suggesting he relocate to Southern California, where the surf was good nearly year-round and the air wasn’t toxic. It left Minnigh with an existential decision.

“I was 35 or 36, and I had been out of the U.S. continuously for 15 years,” he says. “I suddenly realized I’d lived my entire adult life overseas. I thought, ‘Maybe I need to go back to my home country and get grounded again. I mean, who am I?’”

Minnigh landed in San Diego in December of 2006. Roque hadn’t lied—the surf was great, and Minnigh soon found a job helping Chinese immigrants settle into U.S. culture. It was a mellow year for Minnigh, who was renting a room near the beach and surfing almost every day.

The lull was not to last. June of 2007 found Minnigh once again pedaling through Tibet, climbing into the Himalaya toward Nathu La pass. On the other side lay a 50-mile dirt road down into India, a descent they were not to make. A day from the top of the pass, a drunk truck driver accidentally ran Minnigh off the road, pushing him down an embankment and forcing the end of his handlebars nearly through his hand. After splinting the appendage with a spatula, they rode two days back down the way they came, to a village with a—very primitive—clinic.

“They didn’t even have a proper X-ray machine,” he says. “They looked at it and told me it was broken. And I was like, ‘Yeah, I know it’s fucking broken! Now what can you do about it?’”

What they could do about it was realign the bones. What they couldn’t do was provide painkillers of any sort. Instead, they offered Minnigh a cigarette to relax, which worked until the clinic workers began pushing the broken bones back into place. His teammate, Shaun Horrocks, had his camera out and captured the moment—and one of the most iconic images in what became Minnigh’s first feature for Bike.

“So the first big photo of me in Bike was me screaming in pain, while all these Tibetan people are standing in the background like, ‘What the hell is going on?’” – Brice Minnigh

“It turned out to be an insane shot, and Dave Reddick, the photo editor at the time, loved it and wanted to run it as a spread,” Minnigh says. “So the first big photo of me in Bike was me screaming in pain, while all these Tibetan people are standing in the background like, ‘What the hell is going on?’”

As difficult as China, Tibet or the North Pole had been, the height of Minnigh’s “character building” was yet to come. In August of 2007, shortly after having metal plates put in his hand at a hospital in Hong Kong, Minnigh, David Jessop and Stephen Wright once again headed north. This time the objective was a 40-day ski traverse of the Greenland ice sheet, unassisted by wind kites or helicopters, and with each dragging two sleds behind them.

The trouble began almost immediately, when a wave swamped some of their gear on the shore as they were climbing up from the beach. Then, after an overly long struggle to the plateau, Jessop fell into a crevasse. During the recovery, Jessop accidentally grabbed Minnigh’s bad hand, popping both metal plates out of his bones—a problem, considering they still had 35 days to go.

Over the next few weeks, the crew battled through whiteouts and unseasonal amounts of snow, which left them days behind schedule and severely depleted their food supply. Using their satellite phone, they coordinated a helicopter drop of a week’s worth of food. The package ended up in the middle of a crevasse field several miles away, and considering they were on the verge of starving, the group had no choice but to brave a treacherous recovery. While crossing toward the supplies, Jessop fell into a huge crevasse. Expecting to see him with a broken back—if they could even see him at all—when Minnigh and Wright were finally able to wiggle out to the hole, they were surprised to find him on an ice ledge 20 feet down.

As lucky as Jessop had been, they still had to get him out. Through a combination of sheer will and luck, Minnigh and Wright were able to pull Jessop to the surface. Left with even less food than before, the crew was forced to call for a helicopter rescue. But they were alive.

“Physically and mentally, it’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” Minnigh says, “and we felt a real sense of accomplishment for surviving. But we were stupid, and slightly arrogant, to think we could pull it off without hardships. On the way back, Dave said, ‘We conquered it, lads!’ I was like, ‘We didn’t conquer shit. We got out by the skin of our teeth.’

“To this day, every New Year’s Eve, Dave sends me a text or a message saying, ‘Thanks to you and Steve, I lived another year.’”

The implications of that trip—or rather, the other possible outcomes—were not wasted on Minnigh.

“I think the Greenland expedition made me realize an adventure doesn’t have to be the most hardcore thing imaginable to be meaningful,” he says, “especially when I’m riding mountain bikes and surfing and not feeling like my life is in jeopardy all the time. I mean, where do you go next? It’s a question a lot of adventurers face. Who knows, maybe I’ve learned one or two things in these 46 years.”

Having survived the most harrowing experience of his life, in 2008 Minnigh returned to the warmer, mellower beaches of San Diego and made another life-altering decision. While traveling to China for another guidebook, he had been offered a potential position with the Associated Press in Honolulu. He had also been offered a managing editor position at Bike. He chose the latter.

By 2012, Minnigh had officially become the editor in chief of the magazine, and in the years since has assembled his dream team: Photo Editor Anthony Smith, Managing Editor Nicole Formosa, Gear Editor Ryan Palmer and Online Editor Jonathon Weber. He’s continued to travel the world, with and without a pen in hand: Afghanistan, the Republic of Georgia, Colombia, Senegal, Sri Lanka—the list is as long as it is epic, additions to an already impressive resume.

“Sometimes I forgot how many years I’ve been writing, how many subjects I’ve covered,” he says. “I’m just proud of the body of work I’ve been able to accomplish as a journalist. I’ve tried the hardest I could for everything I’ve taken on, tried to do the very best work I can and make it as meaningful as possible.”

It’s dusk as the conversation winds down, the California sunset touching the tops of the trees behind the apartment. Minnigh is a political junkie, and inevitably the topic of the recent presidential election comes up. He has plenty of opinions, and eventually I ask him why, with all his experience and knowledge, he’s stayed at a mountain bike magazine instead of writing for Time or the Washington Post or another heavy-hitting publication. He pauses for a moment before answering.

“I’ve thought about that a lot over the past several years, because I’ve had a couple of opportunities and my name’s out there,” he says. “Since the election, I’ve gotten really fired up and thought maybe I need to go back into news. But I don’t want to go back into news because as a lifestyle it’s just draining. It negatively affects your health, and when I was just doing news I was depressed a lot more often. But it’s made me realize how much I appreciate the really good news outlets we still have.”

Considering he’s covered the collapse of the Soviet Union, the world of multi-billion-dollar finance, edited Communist propaganda articles, and nearly died in the middle of Greenland, I wonder about the value he sees mountain biking having to the larger world in general.

“There are so many things I think are valuable in mountain bike media,” he says. “Over the years, we’ve gotten so many letters from readers about how they were down in the dumps, or had serious drug or alcohol problems or injuries, depression, bad marriages—you name it. People have literally said, ‘Your magazine or this story has helped pull me out of this period and get me excited about riding mountain bikes.’”

As for Minnigh, he finds as much inspiration in surfing as he does mountain biking, and his future goals include ripping short boards and legit trails into at least his 60s. He’s been thinking about chronicling a narrative of his adventures into a book, but like the trips he’s taken with the magazine, they are ambitious ideas that he has no intention of rushing. Until then, he’s content to enjoy where he is, because it’s exactly where he wants to be.

“It sounds corny to say it this way, but surfing and biking are just different ways of communing with nature,” he says. “And I love nature. I love being outdoors. I love taking it all in and riding your mountain bike. You’re always in it, and you suddenly feel alive. And I feel like this is the way I’m supposed to feel.

“I don’t want to define it. I like the fact that it’s undefined, and it’s just a feeling you have when you’re on a perfect wave, or ripping along some ridgeline at 13,000 feet and all you can see is hundreds of miles of jagged mountains. That’s life. That’s living.”