The Big Show The History of Crankworx, Mountain Biking's Biggest Event

Words by Sakeus Bankson

In every sport, there is “the” event. It’s where the legends are made, where the limits are drawn and then broken, where gradual evolution gives way to cataclysmic progression, where the sport’s soul is defined. For hockey, it’s the Stanley Cup. For football, the Super Bowl.

For mountain biking, it is undoubtedly Crankworx. Since its inception in 2004, the Crankworx mountain bike festival has drawn hundreds of thousands of people to Whistler, BC, to watch the world’s best riders compete for a spot in mountain biking’s history. And, if they’re lucky, to watch those riders change mountain biking’s future in the process.

It’s hard to pinpoint specific highlights when an event has, over its 12 years, created new disciplines, launched athletes to fame, and reshaped the seasonal identity of one of the world’s most iconic ski towns; it’s even harder when there are so many such highlights to point out. Darren “Bearclaw” Berrecloth’s massive 360 in 2005. Or when mountain bike legend Brian Lopes won the Air Downhill for the fifth time in a row in 2010. Or Stevie Smith becoming the first person to win all three downhill events in 2012—which was then dubbed the “Triple Crown” of Crankworx. Or hometown hero Brandon Semenuk’s third slopestyle win in 2014. They all changed mountain biking, and they all happened at Crankworx.

Now with two international venues, the event is poised to influence the sport on a global scale. Because when it comes down to it, the sport depends on progression, and progression is what Crankworx does best.

“There’s nothing else that compares,” says Cam Zink, two-time slopestyle champion. “It’s the big show. How crazy the crowd is, how excited the riders are—I’ve had some of the best times of my life there, and it sets the bar high for the rest of the year. Everyone works harder for it. It’s Game Day.”

To truly appreciate the legacy of Crankworx, one must walk the path that led to its creation. Whistler’s early bike scene was mixed but vibrant—during the ’80s the town hosted BMX events, graced by the likes of very young Brian Lopes and Wade Simmons, and on the slopes locals began connecting gravel roads with an ever-growing network of trails. As the ’90s rolled around, there were already some modern favorites, a few of which would eventually turn into classics—like Ripping Rutebaga, which would later morph into Dirt Merchant. By 1995, Whistler was even hosting a mountain bike festival, called the Cactus Cup, with XC races and a dual slalom.

It wasn’t until 1999, when the bike park opened in its current form, that mountain biking truly took off at Whistler, which would soon become known as a premier destination for the burgeoning freeride scene. And that’s when Paddy Kaye entered the picture.

Kaye moved to the area in 1992 from Ontario as a ski bum, but as he stumbled into the bike scene, trails became his main focus. In 1997, he and a few fellow riders started Joyride, a trail-building company that had a significant influence on the beginnings of the bike park. As Whistler’s reputation grew, Kaye and Chris Winter, another Whistlerite biker, decided to start a competition free of UCI, NORBA or other official organizations. And thus, in 2001, the duo organized the Joyride biker cross as part of their larger Whistler Summer Gravity Fest.

Each year brought new contests, such as the Air DH, a 50-jump race down A-Line that was added as a last-minute replacement when the World Cup dropped out in 2002. Soon the biggest international names were gracing the rosters. Something special was brewing, even if Kaye and Winter didn’t know what it actually was.

“It was the first time we saw the hardcore freeride scene, guys like Wade Simmons and kids like Thomas Vanderham, side-by-side with guys like Brian Lopes and Steve Pete and Cedric Gracias, the big names in the UCI events of the time,” Kaye says. “It was cool and casual and it felt like we were connecting some dots.”

Actually connecting the dots, however, required some creativity, particularly in slopestyle. Just as the riders had to figure out what it took to win in this new style of riding, so did those who would be giving out the prizes. Without any established system of scoring, Kaye and Winter brought in judges from snowboarding, who they figured at least had experience with the process. Almost all of those initial overseers are now certified FMB judges, and still score events at Crankworx today. Joyride was onto something.

“We didn’t really know what we were doing for those first events,” Kaye says, “and ended up discovering this whole new discipline.

The other events also earned the approval of their respective all-stars. Brian Lopes, already one of the most decorated and well-known riders of all time, remembers his reluctance to compete his first year in 2002, giving up one of his few open weekends to go to a relatively unknown event.

“I honestly didn’t want to go,” he says. “At the time, I was totally engulfed in World Cup racing, and I just wanted to go home. Then when I got there, I was like, ‘Oh my god, this place is amazing!’ I couldn’t wait to go back the next year.”

Whistler couldn’t either. In a case of organic, grassroots growth, in 2004 the many events and festivals of Gravity Fest were consolidated under Crankworx, a company owned by Whistler Blackcomb, the Resort Municipality of Whistler, and Tourism Whistler. As vice president of business development, Rob McSkimming was a vital (if not the most vital) figure in starting the bike park, and so alongside General Manager Mark Taylor, the duo took the reins as organizers.

Over the next few years Crankworx saw a few different general managers, but one of the most instrumental in helping the even transition from homegrown and grassroots to full-grown and professional was Jeremy Roche, who stepped in as GM in 2006. In 2008, the resort bought the event in its entirety for a dollar, transforming it into a nonprofit organization designed to drive tourism to the area.

In 2010, Darren Kinnaird—who had spent the few previous years working on event sponsorship with Roche—took the Crankworx general manager role, and the current team was formed.

But back in 2004, the event had a new owner, new name and new builder (Paddy Kaye and Joyride left to pursue other projects). Changes aside, however, the level of progression did anything but slow. It was game on.

“As far as progression at the time, everything was at Crankworx,” Zink says. “Each year something new would happen. There were the New World Disorder movies, and there were freeride events like Rampage, but they were kind of sideshow things. Crankworx made it legit.”

A list of the highlights since that initial running would easily fill a book—from the beginning, Crankworx earned a reputation as the arena for explosive progression in a sport that was still very much figuring itself out. With New World Disorder’s films introducing the vague term “freeride,” it was anyone’s guess where mountain biking was headed. This was most obvious in slopestyle, which would immediately become Crankworx’s most glamorous event—and perhaps its most influential.

“Those early years were so awesome, not really knowing what this whole thing was,” Zink says. “It was the coolest contest, but really confusing—people on downhill bikes, hardtails, XC bikes that were starting to look like slopestyle bikes. No one knew its identity and no one knew where it was going.”

Paul Basagoitia’s victory the first year was a prime example. As a BMX rider who had almost no experience on 26-inch wheels, friends convinced him to borrow a bike from Zink and compete in slopestyle. He dropped in, and with a set of tricks yet unseen in mountain biking, he blew everyone away. The bar was set, but no one could have predicted how high that bar ended up being.

Crankworx’s immediate influence on the sport wasn’t just in the slopestyle realm. The Air DH was already adding jumps and flow to the downhill scene. The Garbanzo Enduro DH, in the bike park’s newly opened Garbanzo zone, was longer than almost any other downhill race at the time, pushing top riders like Cedric Gracia, who won in 2004, to an entirely new limit. The next year, Gracia added another notch to Crankworx’s reputation for spectator-pleasing hijinks when he manualed down 1,300 vertical feet of the course after blowing his front tire on the newly built Freight Train.

But perhaps the most remembered moment in Crankworx’s history happened in 2005 during the slopestyle, when Darren Berrecloth threw a 360 over the course’s 60-foot road gap. It was unprecedented at the time, and for both legends like Zink and up-and-comers like Brandon Semenuk, mountain biking had just changed.

“I still remember Bearclaw’s 360,” Semenuk says. “At the time that was a huge feature, and watching him stomp that was the craziest thing we’d ever seen on a bike. It was just insane.”

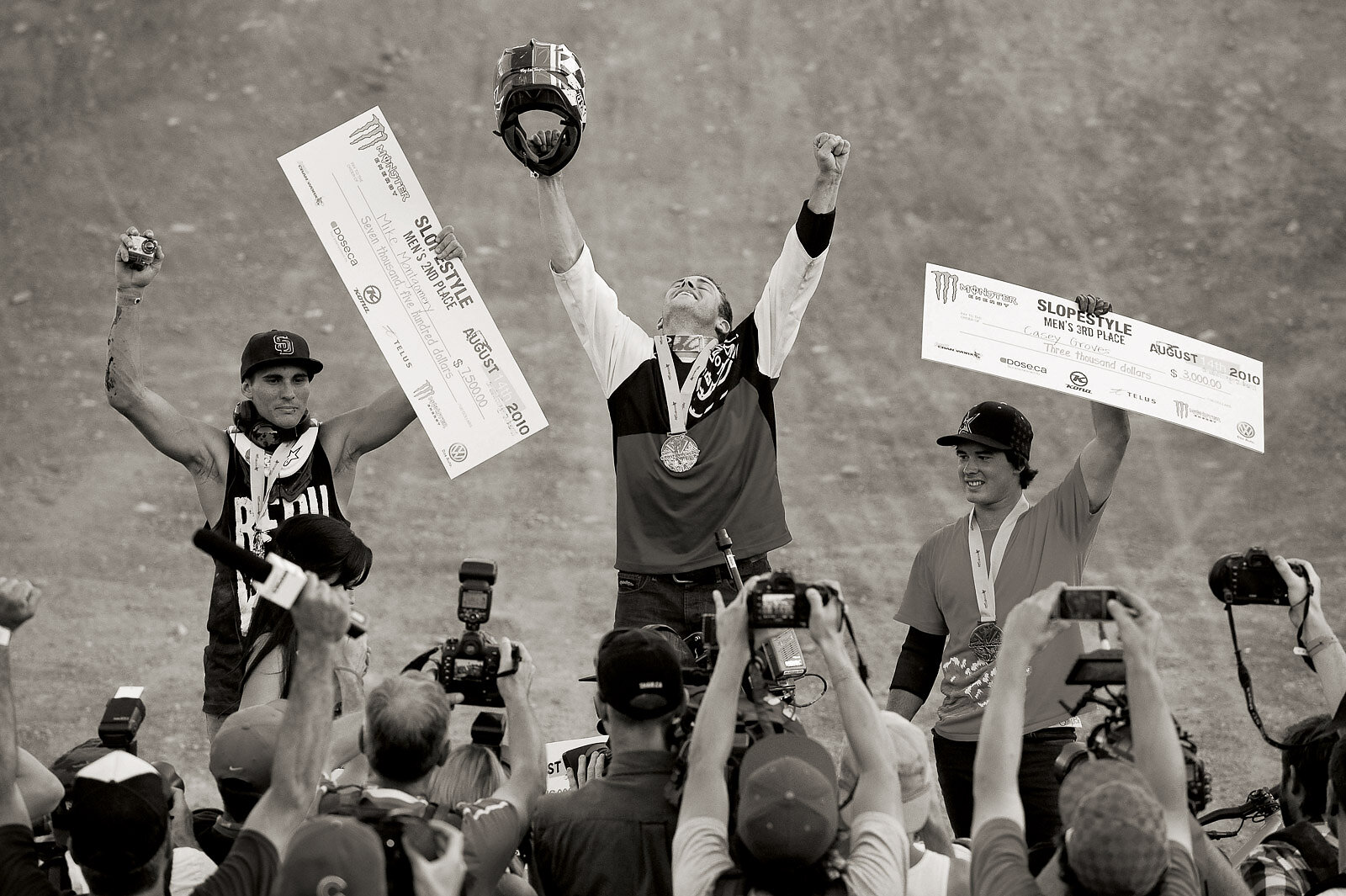

The milestones continued with each year’s event. Zink’s 2006 winning run in the then-Monster Energy Slopestyle set a whole new level of amplitude, and Greg Watt’s victory line in 2009 “would still hold up today—it was like seeing the future,” Zink says. That same year the newly added Canadian Open DH brought a classic-style downhill to the lineup. In 2009, the Deep Summer Photo Challenge allowed mountain bike photographers to compete alongside the athletes. Along with Lopes’ five-peat, in 2010 Zink returned from a barrage of injuries to reclaim the slopestyle title, and Olympic gold medalist Anne Caroline Chausson nabbed three victories herself, in the Garbanzo DH, Air DH and Canadian Open Enduro. The hits just kept coming.

On the organizational side, each year brought new adventures, but sometimes even the failures led to unintentional successes. One example is the resurrection of the dual slalom in 2007. The field was impressive, as was the prize money, so when the timing system failed the evening of the event, it was a big deal. In the interim, some freestyle competitors started playing around on the course, throwing tricks off the jumps. The crowd loved it, and while technically it was a screw up, it eventually led to the 2012 addition of the Dual Speed and Style.

“There have been a few of those kinds of growing pains along the way, as it went from really a grassroots event to something high-end and professional,” McSkimming says. “We’ve had to grow along with it, and sometimes we’ve kept up and sometimes we haven’t. But we’ve always learned a lot.”

By 2011, Paddy Kaye and his company Joyride had already developed a reputation as the best professional trail builders in the world. This included mountain biking’s other most prestigious event: Red Bull Rampage. Crankworx was working with Red Bull as the new sponsor of their slopestyle, and it was through this connection that Kaye got his newest—and oldest—professional building job. For the first time since 2003, one of the event’s key originators would return to the venue he had helped create. The Joyride Slopestyle was born—or rather reborn, and Kaye brought more talent than ever.

“It’s amazing building a course like Joyride, but there’s also a bunch of pressure to get it right,” Kaye says. “It’s similar to what the athletes do: We spend the whole year preparing and building a course that progresses every year, so the riders can do the same, to put on a show that pushes the sport. It all works together.”

That year, Semenuk—a Whistler local—finally won the event after being on the podium three times since 2007. He would go on to win twice more, in 2013 and 2014, becoming the only rider to claim three gold medals in the event and an inspiration for young slopestylers everywhere.

“When we grew up slopestyle didn’t exist—we were watching racers and trying to duplicate that,” Zink says. “Now kids are growing up with these idols like Semenuk, giving them something to strive toward.”

Progress continued in the other disciplines as well. In 2012, Stevie Smith became the first person to take home a Crankworx “Triple Crown” winning all three downhill events. In 2013, the GoPro Dirt Diaries video competition joined Deep Summer as a venue for artists to add to the madness. After a huge swell of social media support, 14-year-old Whistlerite Finn Iles was allowed to ride in the 2014 Whip-Off. He won. At Crankworx, legends of all ages continued to be made.

As far as Whistler itself is concerned, Crankworx has also helped reboot the identity of one of the world’s largest ski resorts. When the bike park was built in the late ’90s, the town was primarily winter-oriented. Partly due to the draw of Crankworx, the town’s summer culture has exploded as well—so much so that it has surpassed the Telus Ski and Snowboard Festival as the biggest event of Whistler’s year. For pow-seekers, Whistler is still a well-established destination. For dirt-seekers, it’s become a nearly holy pilgrimage.

“It brings a lot of new faces,” Semenuk says. “Now there’s a really big mountain bike culture. You see more people doing the mountain-bike-bum thing instead of the ski-bum thing. It’s created this foundation for Whistler to be the Mecca of mountain biking.”

Considering its beginnings, it’s obvious the “big show” of Crankworx has always been centered on Whistler. However, both Kinnaird and McSkimming think its future lies in its ability to travel. As early as 2007, there was already a Crankworx event in Colorado (which fizzled in 2011), and 2012 saw the first running of Crankworx Les 2 Alpes in France. This past year, they’ve added New Zealand into the event’s international roster. 2015 also saw the inaugural Crankworx Rotorua in New Zealand, signifying the festival’s next big step: the Crankworx World Tour. This brought a whole new level of global interest, especially via the interwebs.

“These last few years we’ve been able to see where people are watching the live webcast, and some of the countries are in the middle of nowhere, places you’d never think would know about mountain biking, let alone Crankworx,” Kinnaird says. “Tanzania, Sudan, Botswana, Namibia, Macedonia—it’s really weird to see where people are watching from. Five hundred in Indonesia tuned in for the Rotorua slopestyle. It’s pretty amazing. I mean, who are these people?”

On the administrative side of things, the potential this presents is huge. The tour now has its own downhill and enduro races—including the Whistler stop of the Enduro World Series—as well as the Triple Crown of Slopestyle and King and Queen of Crankworx. That’s quite the jump from its homegrown beginnings.

“It’s taken on a life of its own in some ways,” McSkimming says. “It’s gone from a small regional thing to a worldwide tour that gets a worldwide audience that attracts the best international riders in the sport. When you think about it in that context, it really has come a long way in a short period of time.”

One major entity has remained absent from the Crankworx lineup: the UCI World Cup, particularly the downhill circuit. It’s the most vaunted competition in the discipline, but the momentum Crankworx has built is all its own. And, according to many of the biggest names in the sport, it should stay that way.

“Anyone in biking, especially on the management side of things, would want a World Cup event at their home mountain,” Lopes says. “I know the Whistler folks have wanted to bring something like that to Crankworx without much success, but I don’t think they really need the UCI—if anything, the UCI needs Crankworx.”

Now in 2015, Crankworx has set another standard in the world of competitive mountain biking: for the formation of the World Tour, prize money is equal for men and women on the podiums, making Crankworx the first event to do so. There’s more to progression than just tricks and race times.

As for Joyride, the crown jewel, Kaye thinks they’ve developed a style that works for both fans and riders—a very reasonable assertion, as 2014’s finals saw a record 30,000 on-site spectators. Kaye plans to leave the massive, moto-sized hucks to venues like the Fest Series, and instead focus on honing in the course to accommodate slopestyle’s increasingly technical trick set.

“It’s hard to say, but I don’t think it’s going to get much bigger,” Kaye says. “I think it’s just going to get more refined. I can’t really see an 80-footer happening at Joyride, but you never know. For me personally, I’m just absolutely honored to still be involved and be able to have impact on where this sport is going.”

Fifteen years since that initial Joyride slopestyle and 12 since its official birth, Crankworx has become the biggest event in mountain biking and continues to push the limits of the sport. Perhaps more importantly, however, is its role in growing mountain biking in general.

“I think it’s brought it to the masses, a celebration of the sport’s culture on a larger stage,” Kinnaird says. “A lot of folks who are exposed to the event leave with the feeling that Crankworx is mountain biking.”

And as the sport continues to grow, so does Crankworx, thanks to the administration, builders, fans and athletes that have carried its progression along the way. It’s been a group effort, but two folks remain integral to the event’s influence and evolution.

“I think Rob McSkimming and Darren Kinnaird—really the whole crew up there—are doing an incredible job,” Lopes says. “They’re always open to listening to the riders, taking feedback and implementing it as well as they can, and I think that’s what’s made it what it is: an event that everyone, both riders and spectators, look forward to going back to.”

As for future athletes looking to put their names in Crankworx’s hallowed halls? This is the wisdom Mr. Zink would pass along: “To anyone on top of the drop-in for the first time, the best advice I can give is to have fun with it,” he says. “It’s probably the best time you can ever have on a bike.”

![“Brett Rheeder’s front flip off the start drop at Crankworx in 2019 was sure impressive but also a lead up to a first-ever windshield wiper in competition,” said photographer Paris Gore. “Although Emil [Johansson] took the win, Brett was on a roll of a year and took the overall FMB World Championship win. I just remember at the time some of these tricks were still so new to competition—it was mind-blowing to witness.” Photo: Paris Gore | 2019](https://freehub.com/sites/freehub/files/styles/grid_teaser/public/articles/Decades_in_the_Making_Opener.jpg)