Welcome to Issue 12.3

With this year’s riding season in full swing, Freehub pays tribute to a return to trails and travel with our 12.3 edition—a stoke-filled book honoring progression in many forms. Every step forward contributes to the advancement of the mountain bike community, and this issue examines successes big and small. In the rugged state of Nevada, impassioned individuals are working selflessly to revitalize former mining communities through outdoor recreation and trailbuilding, with lifelong ranchers and freeride luminaries such as Cam Zink (featured on our cover) sharing the same objectives. In Harrisonburg, Virginia and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, hardcore riding communities are infusing a new generation of riders with a heartfelt appreciation for the value of old-school, technical singletrack. And on the hallowed slopes of Vancouver’s North Shore, original freeride pioneers still mingle with their ultra-talented progeny, proving that progression is a constant—and that it begins with each of us. Welcome to Issue 12.3.

I’m not often accused of being an optimist. In my baby book my parents described me as “solemn” and the jaundiced eye I have pointing outward is, I feel, perfectly suited to the current state of the world.

Except in the mountains—and especially on exploratory trips with a great number of unknowns.

In those situations you’ll find me rallying the crew with just one more hike-a-bike in my eternal search for the promised goods. I call it mountain optimism.

Case in point: I’m pushing my bike up a steep slope in southwest Montana with friends Erin Bergey and Nicki Trimble and looking for a trail I insist will appear any second. So far, all that has appeared anywhere near our feet are the cheatgrass burrs biting our calves.

“The next hill is the last bit of climbing,” I promise them.

Words and Photos by Aaron Theisen

There’s no doubt that the sprawling state of Nevada is harsh and rugged.

Not only is it the United States’ driest state, but it’s also the most mountainous of the lower 48, marked by seemingly endless stretches of barren mountain ranges. The alternating landscape of mostly parallel ranges and valleys—known as “basin and range topography”—has long made it one of the country’s most inaccessible regions, and it has historically been much more known for mining than mountain biking. Yet nestled within these mountains’ fringes are pockets of pure mountain biking gold, with patch-works of singletrack spreading throughout the edges of population centers.

Boasting 172 mountain peaks with at least 2,000 feet of prominence, Nevada has plenty of relief to go around. Mix this with the country’s highest percentage of federally owned land and low population density, and you have a recipe for what a handful of passionate trailblazers believe will be mountain bike paradise. Alongside lonely highways and ramshackle rural towns lay a cache of growing mountain biking hubs where the impetus to build trails and nurture riding communities is as tenacious as the terrain itself.

Words by Brooke Summers Hume | Photos by Steve Lloyd

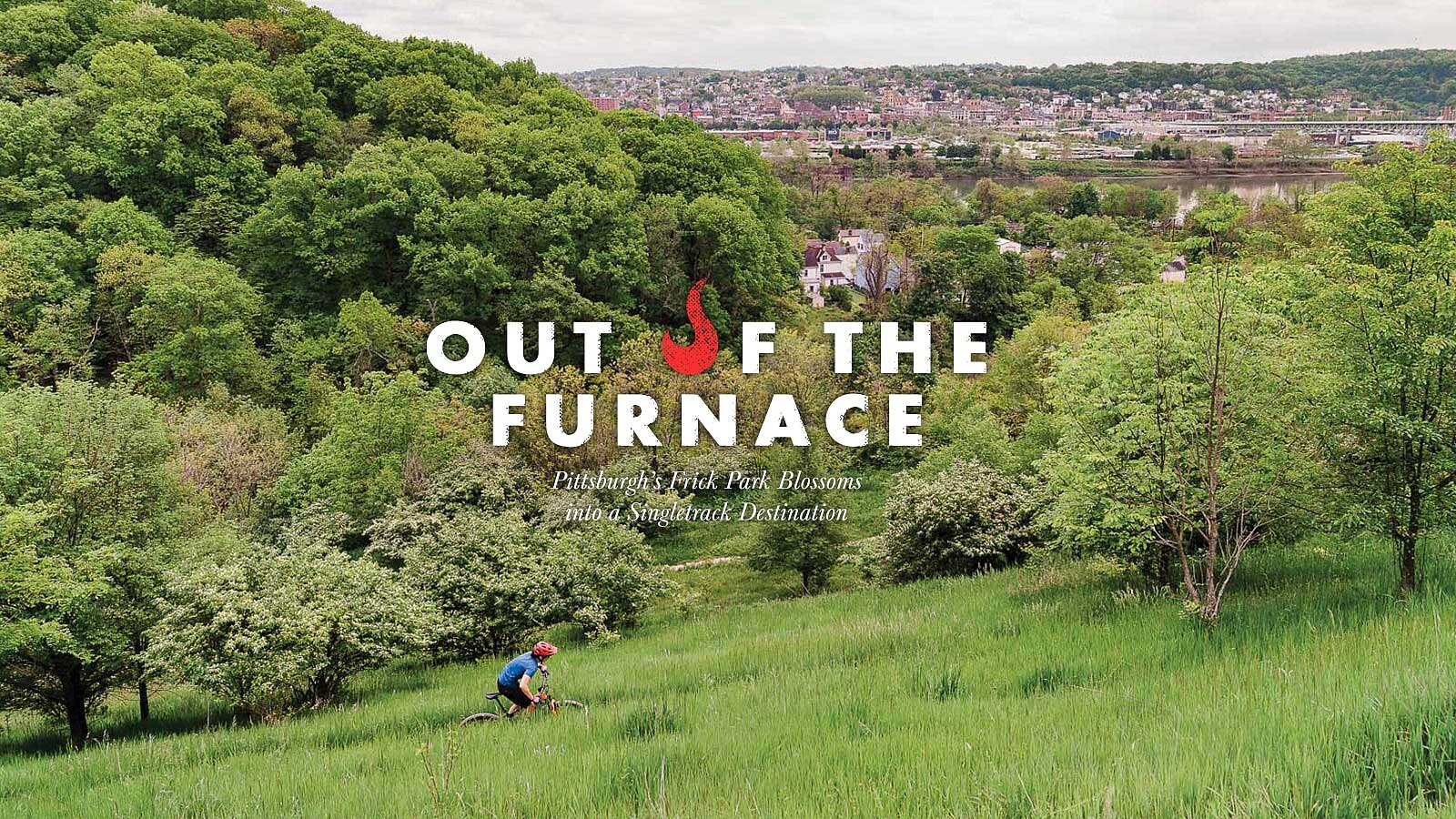

Steep hills are more ubiquitous than steel mills in Pittsburgh. Outsiders often overlook this hallmark feature of a city long dominated by the stereotype of factories billowing with fire, soot and smoke.

First documented in gritty detail by eminent American photojournalist W. Eugene Smith, Pittsburgh’s working class once made their way down the city’s punchy hills and intricate networks of stairs on foot to toil away at tough jobs producing coal and steel. Demand for such work has tapered and, since then, companies such as Uber and Google have moved in as tech steadily replaces physical industry. And while locals still negotiate the same hills as their forebears, a growing number now do so aboard mountain bikes. For these riders, Frick Park, covering over 644 acres of dense forest and ravines east of downtown, is the jewel of Pittsburgh’s mountain biking scene.

“It’s hard for me to imagine living in a city without a Frick,” longtime Pittsburgh rider and trailbuilder Randy Nickerson says. “The park isn’t without its occasional city park quirks and characters, be it rolling up on a trailside porno shoot or being confronted by a hatchet-wielding madman,” he says, recalling two weird situations he’s encountered at Frick Park. But more often Nickerson describes riding at Frick as a “drastic welcomed departure from the grit and pace of city life without actually leaving the city limits.”

For the earliest generation of Pittsburgh mountain bikers, Frick Park provided a blank slate upon which to create trails and test the limits of equipment. In the early 1990s, a handful of eager riders began scratching in the first rideable trails and, by the turn of the century, builders had established a network of singletrack totaling about a half-dozen miles. Early favorites were Nature Center (originally known as Stove Top) or, more recently, Bradema, depending on who you ask.

Words and Photos by Brett Rothmeyer

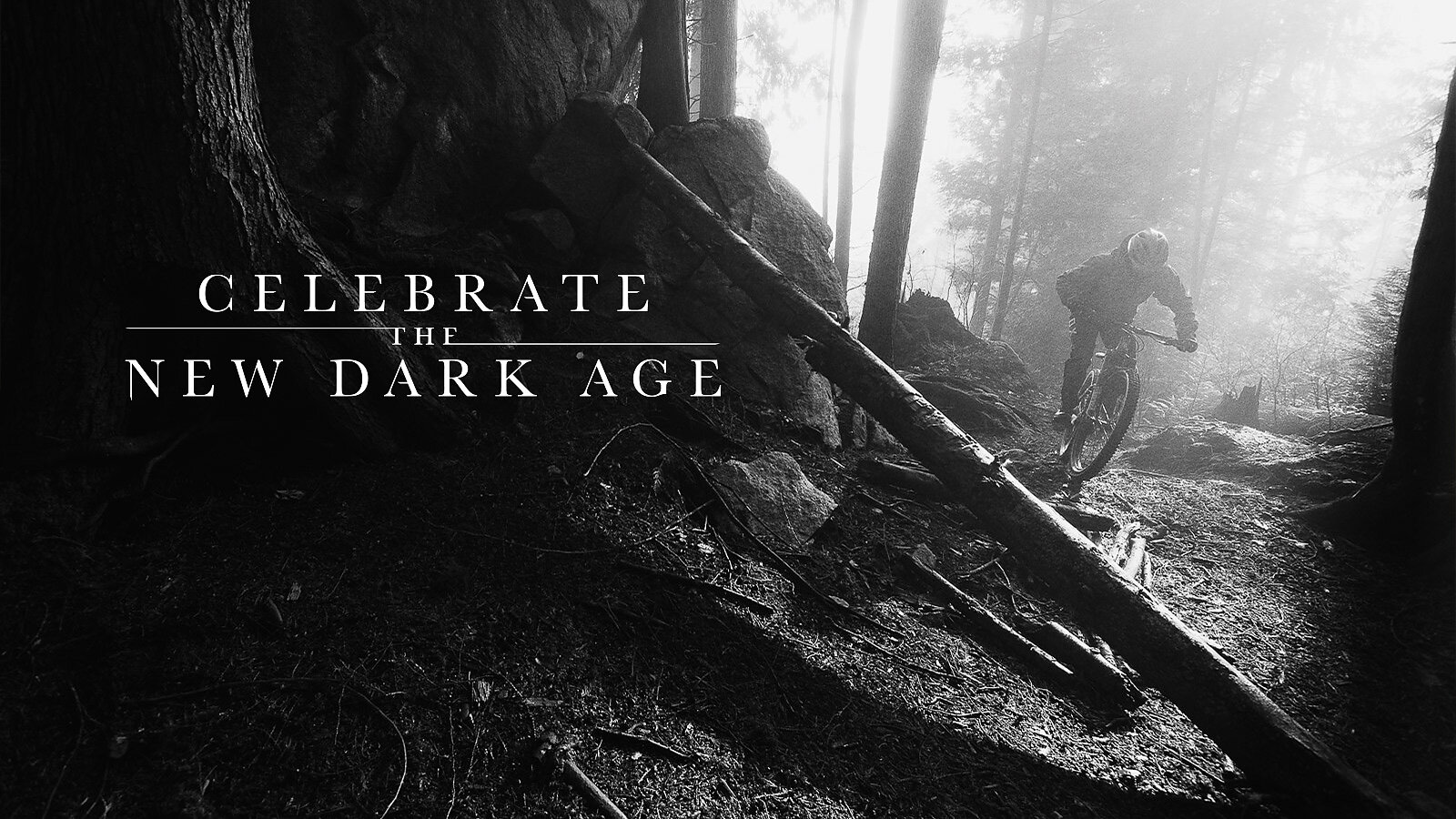

All things that grow and flourish are in a state of continuous change, subject to decline and destruction. On Vancouver’s North Shore, this idea of impermanence can be witnessed as new trails get scratched in beside the skeletal remains of decaying ladder bridges.

Day by day, newer, faster and more aggressive lines have replaced artifacts from rad times of yore at the turn of this century. At this juncture, the only constant that remains is the dark, brooding and uncompromising nature of the Shore with its steep, forested slopes shrouded in mist. Matching the ever-changing moods of this infamously rugged landscape, the geometry, suspension design and materials of mountain bikes have undergone periods of radical evolution. Emboldened by technology and inspired by history, riders who grew up on a steady diet of freeride from an early age continue to redefine what is possible, ushering in bold perspectives on mountain biking in North Vancouver. This project isn’t about remembrance. It’s a celebration of change—a new age of riding on the Shore is here.

Words and Photos by Dave Smith

Straddling his bike on Colorado’s Grand Mesa amid brilliant fall colors, days before the first winter storm put trailbuilding season into hibernation, Greg Mazu surveyed the painstaking rock work and bench cuts along the edge of a precipitous cliff overlooking the town of Palisade.

“Too many people think trails magically get built by fairies and elves, but they’re wrong,” Mazu said. “This trail got built by nomads and misfits.”

With completion scheduled for this summer, the Palisade Plunge is the crowning achievement of Singletrack Trails, Incorporated (STI), a company Mazu started in 2004. Covering 32 miles from the top of Colorado’s Grand Mesa at 11,300 feet of elevation—the largest flat-topped mountain in the world—the Palisade Plunge descends a total of 8,000 vertical feet with 2,000 vertical feet of climbing, finishing in Palisade on the banks of the Colorado River.

The only thing more impressive than the dirt and rock artistry of Mazu’s nomads and misfits is the time it took, or rather didn’t take, his crew to construct this masterpiece.

“We started in May 2019 and both phases of construction were completed in less than two years,” Mazu said, “Each time I’ve ridden the trail, I found myself repeatedly saying ‘holy shit’ because of the terrain our crew worked through and that they still work for me after all they endured.”

Words and Photos by Aaron Theisen

Sitting at 1,325 feet in the heart of Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, you’d be forgiven for mistaking Harrisonburg as little more than a blue-collar college town.

From Interstate 81, the only hint of this East Coast mountain biking hub you can actually see is James Madison University’s bluestone campus. In-town views of the mountains are overshadowed by the Cargill grain elevator, Harrisonburg’s tallest structure, rising above downtown like a cinder block tribute to the city’s agricultural roots.

The mountain bike scene in the ‘Burg is not immediately apparent, though it has been vibrant here since the dawn of off-road riding. Harrisonburg is not overrun with mountain biking tourists. Driving to the trailhead, you’re more likely to pass a Mennonite family on horse-and-buggy than a car bearing a bike rack. Of the hundreds of miles of singletrack that surround Harrisonburg, less than 10% of them are bike-optimized and only a handful are rated green for beginners. But what is here is a quietly thriving community of cyclists working to bring the region’s rugged backcountry networks to the next level.

That the ‘Burg is a place with a reputation for going big is undoubtedly a reflection of its topography. Prior to the city’s founding in 1780, Harrisonburg was known as Rocktown, and for good reason. Jagged flakes of limestone jut from the fertile valley floor as 3,000-foot parallel sandstone ridgelines hem Harrisonburg’s horizon. Massanutten Mountain and the Blue Ridge Mountains flank the city to the east while the Allegheny Mountains loom to the west. And though the city has both Skyline Drive and Shenandoah National Park at its doorstep, for mountain bikers in Harrisonburg, the true gem is the 1.8-million-acre George Washington and Jeffer- son National Forests.

Words and Photos by Jess Daddio

Each year, mountain bikers are spending more time in the air than ever before.

The advent of the modern flow trail, with its manicured, machine-sculpted perfection, has catapulted us into a new era of high-speed progression. Advanced trailbuilding techniques allow for berms that border on wallrides, ricocheting us from one banked turn to another like they’re the flippers of a pinball machine. Our understanding of jumps has evolved to a space where science meets art, resulting in tables and transitions that squeeze every ounce of speed from what gravity offers— often without the need to pedal.

At the same time, quantum leaps in bike geometry and suspension technology have changed the way many of us read terrain. Obstacles are now opportunities, with rocks, roots and even the slightest bumps on a trail serving as launchpads to airborne freedom. Clever preloading of our suspension is sling-shotting us farther and higher, and a new generation of riders is, arguably, milking as much time in the air as it is on the ground.

All these factors have made the average ride much more predictable and, in many respects, much safer. But with our overall increase in velocity—and our tendency to hurtle through space more often—the consequences can be greater when things go wrong. And with more people mountain biking than ever before, many progressive trails have become congested with punters of staggeringly different skill levels and experience, often making your fellow rider the biggest potential threat to your own safety.

Words by Brice Minnigh | Illustration by Victor Brousseaud

The durability of aftermarket bike products rarely lives up to advertising hype. Bombproof? Bulletproof? Nukeproof? Hardly. Simple fact is, we as consumers are the guinea pigs.

That next-generation space-age material used on an F-16 fighter jet must be strong enough for a bike, right? Maybe, until that high-dollar carbon crank arm that used to be a missile fuselage splinters in half and finds part of itself impaled in your calf muscle. Along with the quest for Herculean strength, we mountain bikers also continually look to drop an extra hundred grams of weight off our bikes, never mind the night before when we guzzled a sixer of Coors Light and ate a Big Mac—supersized of course. But then there is the genre of mountain biker concerned with neither strength nor the weight of money-sucking aftermarket components. Their concern is, primarily, how rad does this thing look on my ride?

Rad seemed to be the only thing on the mind of a man—I’ll call him the Bunnyhopping Rockstar—I met in the summer of 1995 at a barbecue cookout near Pittsburgh hosted by Dirty Harry’s Bicycles and the now-defunct Dirt Rag magazine. Sure, minimal weight and strength were added benefits, but when it got down to business, Bunnyhopping Rockstar only cared about the rad factor. Long wiry blonde hair down past his shoulders, tattoos on his thin, pale, sinewy arms, a scent of sweaty armpits and cigarette butts and a nonstop air-drumming routine that must have contained more invisible toms than Neil Peart’s 1984 Rush world tour kit were just a few of this character’s distinctive traits.

He was impossible to miss. The dude jumped around with more vigor than a 6-year-old on a pogo stick. His ratty hair bounced up and down and flowed more elegantly than a horse’s mane. He had a Walkman on and every so often, when a really good drum solo was coming, he’d stop hopping and put on an in- visible drumming spectacle that kept me in awe. Boom! Dugga-dugga-crash-ch-ch-ch-Chang-ka-kakakaka-Kow! Boom! Snare! Crash! Gong!

Words by Kurt Gensheimer

As soon as Steffi and Micayla began telling me stories about broken bones, collapsed lungs and being paralyzed from the waist down, I thought maybe I was making a mistake.

Who am I to write about getting injured? I’ve had long recoveries and ongoing chronic pain, but I’ve never faced multiple surgeries or known the weight of learning to walk again. The truth is, if it was only my story, I probably would have kept it to myself. But this is bigger than me—this is about all of us.

It started with an unexpected invitation. The email said I had less than 24 hours to make it to Portugal for the ride of a lifetime. The thought of racing to board an airplane felt jarring as I sipped coffee from the cozy confines of a friend’s Copenhagen apartment, slowly recovering from a late night of dancing in Berlin. But adventure called, loudly, and I booked a flight leaving at 4 a.m. the next morning to Lisbon.

As hurried trips go, this was already shaping up to be the kind where if everything went just right, there would still be a strong possibility of calamity along the way. And as the type of guy who doesn’t often get invited to ride in far-flung destinations with professional athletes—my nonexistent networking skills and utterly insignificant role in the bike industry don’t exactly make for many beguiling escapades—I had to pinch myself as I sat shotgun in a taxi with a Portuguese stranger named Hugo as we sped off, chasing only the promise of a good time.

Words Skylar Hinkley and Illustrations by Albert Mercado