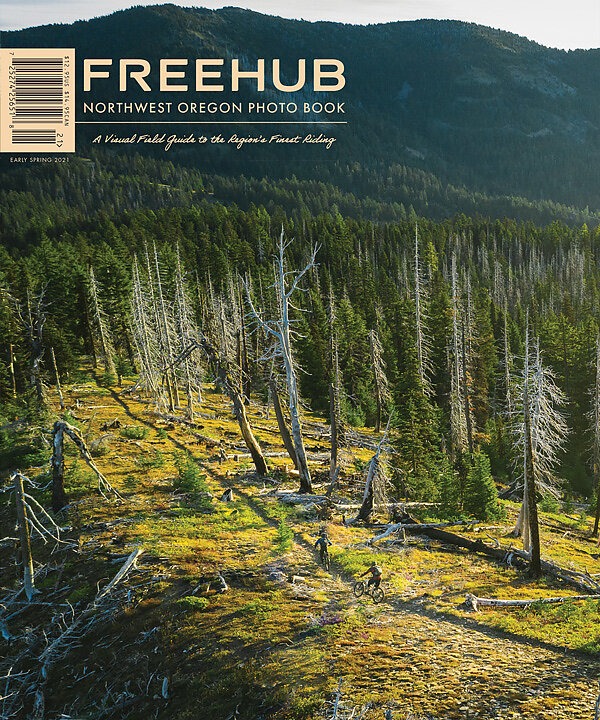

Welcome to Issue 12.1

As Freehub enters its 12th year of coffee-table book publishing, we’re proud to present this special Northwest Oregon Photo Book—a visual field guide to one of the planet’s greatest places to ride a mountain bike. Though Northwest Oregon’s striking diversity of landscapes and climates naturally lends itself to world-class riding, the trails themselves were transformed by the people who’ve lived here: the native inhabitants who first created them, the loggers who built access roads and the mountain bikers and equestrians who have expanded and maintained them over the last several decades. This weighty book is a tribute to these people, with extensive photo galleries, stories and maps highlighting the region’s finest riding destinations and chronicling how they came to be. From the growing networks near the outdoor-loving cities of Portland and Bend to the storied trail systems surrounding the timber-rich towns of Hood River and Oakridge, this carefully crafted manual paints a vivid picture of why these extraordinary places should be at the top of every mountain biker’s bucket list. Welcome to Issue 12.1.

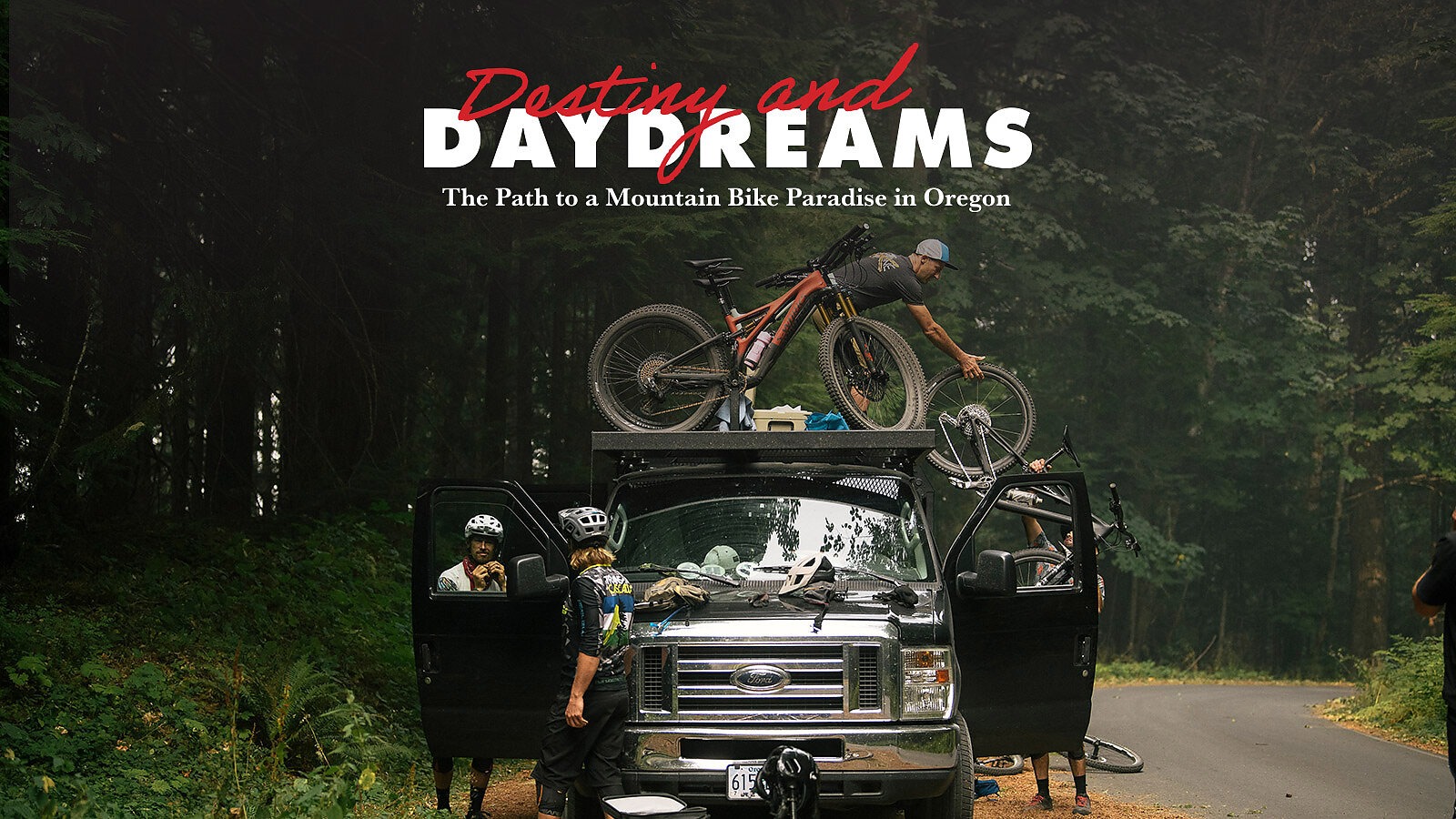

Do you believe in destiny? Part of me likes to think so, and I’d like to think destiny is also why you’re reading this article.

My connection to the great state of Oregon could have everything to do with destiny, too, stemming all the way back to my Midwestern childhood, when I grew up playing a computer game called The Oregon Trail.

This game was designed to teach schoolchildren about the realities of 19th-century pioneer life on the Oregon Trail. Each player assumed the role of a wagon leader guiding a party of settlers from Independence, Missouri, to Oregon’s Willamette Valley, using a covered wagon during the Gold Rush of 1848. The interactive game required players to complete simple math equations, make navigation decisions, hunt for food, shop for supplies, know when to rest, and, most importantly, to daydream about frontier life.

Fast forward to 2007, 20 years after my last game of Oregon Trail, and I’d found myself living in Oregon, helping guide mountain bikers on the trails covering our vast landscape. Oregon boasts a perfect blend of ecology, geology and topography, resulting in terrain that feels designed for the mountain bike. It’s the place you dream of riding.

Words by Nick Gibson & Adam Craig | Photo by Paris Gore

At the confluence of the Columbia and Willamette rivers lies the fascinating city of Portland, Oregon, a place whose alluring natural attributes are rivaled only by the independent and progressive mentality of its inhabitants.

With its rivers lined with bike paths and crossed with bridges, Portland’s layout lends itself to an outdoor lifestyle, and bicycles of all types are a preferred medium for both transportation and recreation.

While urban and commuter bikes are de rigueur within the city, mountain bikes have become increasingly popular in recent years, and today Portland boasts a burgeoning mountain bike community that is on the verge of exploding. Like most metropolitan areas in the United States, there are precious few trails within the city itself, but Portland’s proximity to open landscapes and the foothills of the Cascade Range means that singletrack networks abound just a short drive from the downtown core.

On any given day, Portlanders can be seen loading bikes onto their vehicles and heading out of the city in all directions, inevitably bound for a trailhead leading to a diverse array of singletrack. Unlike many of the country’s large cities—where the average inhabitant is more concerned with finding a high-paying job than spending time outdoors—Portland’s population is increasingly defined by a shared desire for a life balanced between work productivity and an outdoor lifestyle. Attracted by this balance of work and play, and drawn by the promise of craft beer, craft food and even craft bikes, more like-minded people are moving to the city. The economy is booming, the skyscape is transforming, and the demographic is diversifying. And mountain biking is fast becoming one of the common threads that binds Portlanders together.

Photos by Aaron Blatt & Dylan VanWeelden

When an historic winter storm wreaked havoc on the Hood River Valley in January 2012, the mountain bike community watched in frustrated horror as destruction to surrounding forests mounted.

For days, wrist-sized branches coated in thick layers of ice sagged and eventually snapped, the noise echoing like gunshots across the frozen town.

Dispatchers worked day and night fielding calls about downed electrical lines and splintered power poles. The moment the icy roads became remotely navigable, a handful of anxious trailbuilders, mountain bikers and county forest managers made a beeline to the trails to see what was left.

“I went straight to Grape Smuggler,” trailbuilder Gary Paasch recalls. “I was crushed. Huge trees were thrown across the trail. If you didn’t know what you were looking at, it was hard to even tell where the trail was. I knew I would never rebuild Grape Smuggler back to what it was. The county was going to log it, and my heart wasn’t in it to re-create the trail that I worked on for the better part of 10 years. But deep down I knew there was something bigger that was coming. I just couldn’t see it yet.”

Words by Elle Ossello | Photos by Alexandra Erickson

Resting calmly at the base of the eastern Cascade Foothills, straddling the Deschutes River as it tumbles over lava rock in Central Oregon’s high desert, the town of Bend has a split personality.

The river forms a dividing line between mature ponderosa forest to the west, with sage, juniper and grasses fading east into the desert. The west side of town is all about recreation, with trailheads, river access and snowy peaks. On the east side are sprawling neighborhoods, light industry, ranching and a Wild West way of life.

With some of the earliest known evidence of human habitation in North America just 100 miles to the southeast at Paisley Caves, humans have been enjoying the relative ease of travel through Oregon’s high desert for 14,000 years. Fast forward to the 19th century, when early settlers found a rare ford of the river at a place that came to be known as Farewell Bend, and progress as we now measure it began.

The first sawmill was built near Pilot Butte in 1901 and the town grew quickly on the back of the timber industry. This boom continued for decades before tapering off in the 1980s and 1990s. At that time, Bend’s personality began to shift, as many mountain towns have, toward a recreation-based economy that is still supported by the tim- ber industry, as exponential population growth continues to drive the housing sector.

Words by Adam Craig | Photos by Tyler Roemer

Among the places reputed to be the Pacific Northwest’s premier riding destinations, few have a stronger claim than Oakridge, Oregon.

Squarely centered within the contiguous Willamette National Forest, its location enables riders to easily trade the mundane trappings of civilization for the Cascadia paradise of pristine meadows, lush forests and rugged ridgeline vistas.

Aptly described in the City of Oakridge charter as the “Mountain biking capital of the Pacific Northwest,” the township serves as a hub for endless adventure, with each trail network acting as an access point, or spoke, in the overall wheel that is the surrounding Middle Fork Ranger District (MFRD).

“It depends on what you’re after, but Oakridge really does have it all,” Kevin Rowell, MFRD trails manager, says. “You can either ride to the trailhead via a combination of gravel road connections to singletrack or shuttle just about any style of riding your heart desires.”

Words by Michelle Emmons McPharlin | Photos by Trevor Lyden

A good friend of ours recently took a road trip to Utah with several buddies in search of sunshine and some of that celebrated slickrock goodness.

After months of COVID- 19-induced isolation and a sustained stretch of Pacific Northwest gloom, the crew was understandably ecstatic to arrive in the open desert and ride bikes under sunny skies.

For riders accustomed to the greasy rock rolls of a Bellingham winter, the unparalleled traction of the Moab-area sandstone was mind-blowing. It seemed they could ride anything, at any speed, with few consequences. Though they noticed the painted arrows blazed onto the sandstone at regular intervals—clear signs of a designated route—some chose to ignore them in favor of myriad other lines that proved irresistible. The many ancient, wind-sculpted bowls were perfect for wallrides, and even the steepest of rock rolls simply begged to be dropped.

As they approached a juncture with another trail, one member of the group decided to go way offline, charging into a steep rock roll and fishtailing his way through a crispy layer of black crust coating the sandstone surface. He cleaned it with ease, bottoming out at the trail junction and whooping triumphantly at a horrified cluster of local riders gathered around the trailhead sign.

“Uh, dude,” one of them said in palpable annoyance. “You’re not supposed to ride off trail here. You just skidded through thousands of years of crypto, bro.”

Words by Brice Minnigh | Illustration by Victor Brousseaud

Even though Hood River, Oregon is a long way from British Columbia, the Family Man zone of the town’s Post Canyon trails gave pro rider Hannah Bergemann her first taste of freeride stunts inspired by Vancouver’s legendary North Shore.

The Family Man skills area is essentially a mountain bike playground filled with skinnies, jumps and drops of varying shapes and sizes. As a teen, Hannah loved to spend long afternoons sessioning the different features, determined to progress from one to the next. Her favorite trail, Drop Out, captured her imagination with its many wooden freeride builds.

“In the beginning, that’s what got me excited about riding,” Hannah says, adding that freeriding held much more appeal than her early forays into mountain bike racing. Trying to find the fastest lines and obsessing over race results wasn’t really her cup of tea. Instead, she was more interested in hitting jumps and honing her skills on challenging terrain.

Fast forward six years and the only things that have changed are the size and scale of the jumps and drops. That, and the fact that she’s a rising talent in the freeride community, having made a name for herself on the Enduro World Series race circuit and during Formation, a weeklong progression camp aimed at elevating the wom- en’s freeride movement. Along the way, she’s picked up segments in videos and high-profile films, and during the summer of 2020 she scored a coveted Red Bull sponsorship. It’s safe to say we’ll only be seeing more of her.

Words by Katie Lozancich | Photo by Skye Schillhammer

Beyond the bounty of backyard riding spots that come and go with each passing generation of kids, there are always those that remain nurtured over time and expanded until they become “destinations” in their own right.

In many cases, the widespread popularity of these riding destinations helps the nearest town transition from a dying industry to a recreational zone, breathing new life into the local economy and giving the community an altogether new identity and purpose.

While the transition stories of former logging towns such as Oakridge, Oregon might be better known, those of other towns across the state are only starting to take shape. One such place is the sleepy coastal community of Pacific City, a once-thriving fishing and logging town that is reinventing itself as a tourist destination. Though it’s become popular for water sports such as surfing and windsurfing, the rich dirt and singletrack potential of the surrounding forests is just starting to be tapped by local mountain bikers.

At the forefront of this movement is Josh Venti, a landscaper who is melding his passions for riding and working in the dirt into a future of trailbuilding and advocacy. Josh’s discovery of mountain biking didn’t occur until about 10 years ago, when he was languishing behind a desk in the office of Bros & Hoes Landscaping, a company he’d started with his brother. After losing a coin toss, Josh had been relegated to office work and had become 90 pounds overweight. As work took precedence over wellness, he’d slipped into unhealthy patterns and realized he needed to turn things around.

Words by Bryan Cole | Photos by Trevor Lyden