Welcome to Issue 9.4

It’s nice to escape. Whether that’s a day out of the office or a weekend without cell service, there’s something to be said for straying from our normal routines. Mountain bikes offer this opportunity on a continual basis—mountain bikes and a slice of singletrack can take us anywhere. From uncharted peaks just beyond our backyard, to the Himalaya or the towers of Patagonia, there’s freedom to be found on two wheels. Freehub Issue 9.4 is dedicated to tales of adventure and escape, telling the stories of people and the extraordinary places their bikes take them.

It was a Tuesday morning in the fall of 2002 when I walked into my local bike shop and sat down in that one chair that’s meant for the loitering regulars.

It was probably too early for a beer so the shop manager, Scott, handed me a mug of coffee.

“How was your race last weekend?”

“It fucking sucked. I broke my downhill bike in practice, then I had to race my hardtail on the craziest course I have ever seen, and then my bike sponsor decided they weren’t going to have a team next year.”

“Damn. What are you going to do?”

“I don’t know, man. I think I’m just going to take a break and not ride for a while. Maybe get a new hobby. I’ve been a one-trick pony for a long time...”

Words and Photos by Chris Reichel

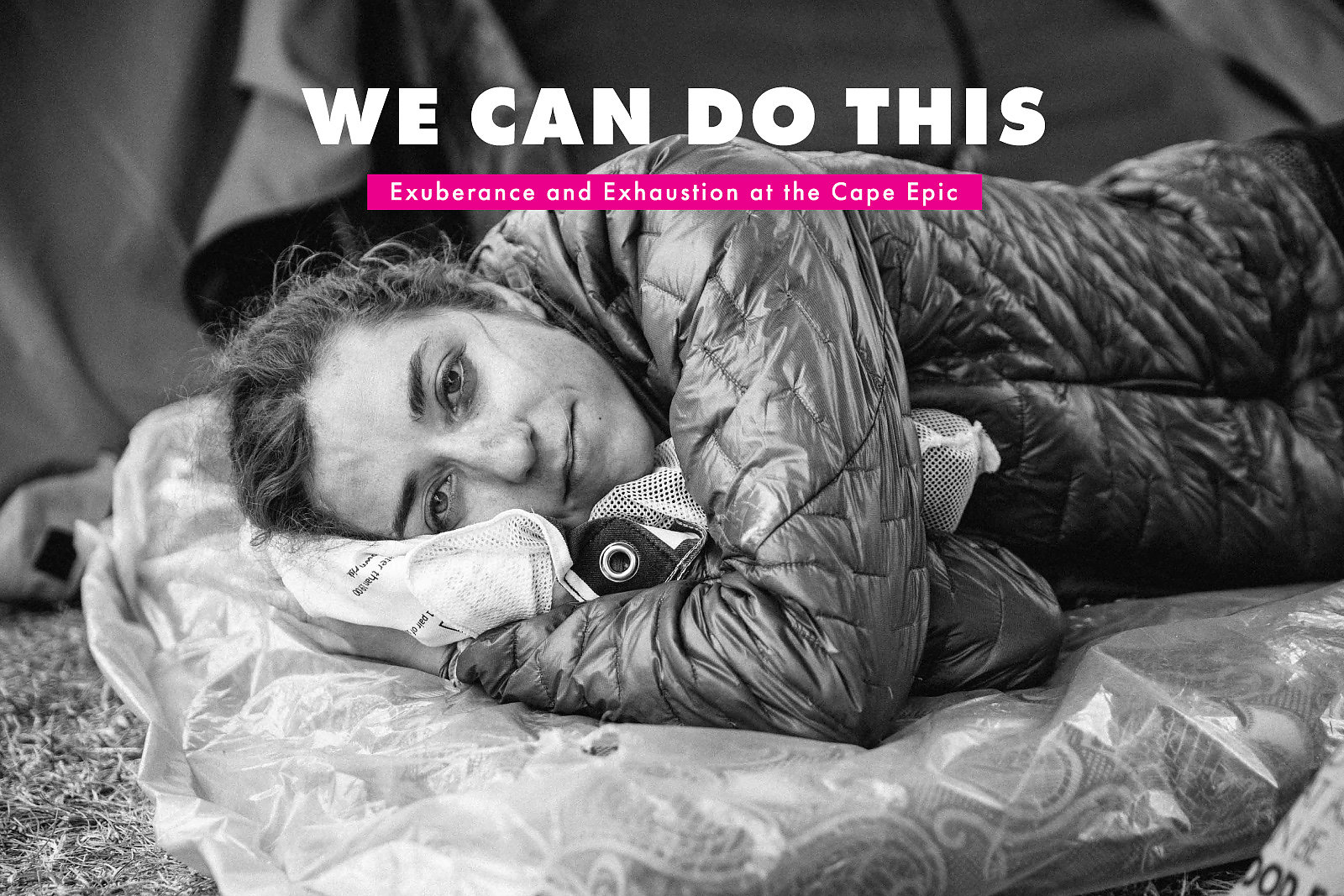

At the sound of predawn bagpipes on the final morning of the 2018 Cape Epic, I awoke, and sat up slowly.

I was empty and weak, but I was OK. I rolled over and nudged my riding partner, Kaysee Armstrong. “We can do this,” I said. “We can pedal our bikes. We don’t have to pedal fast, but we can pedal. We can finish this thing.”

The look in Kaysee’s eyes broke my already-broken heart. She nodded. “We can do this.”

Called the Tour de France of mountain biking, the Cape Epic is an eight-day team mountain bike stage race that takes place each March outside Cape Town, South Africa. “Team” is one of the key points of the Cape Epic. Over those eight days, two-person teams cover 400 miles and climb 44,000 feet, and they must never be separated by more than two minutes for the entirety of the race. I met Kaysee the day we arrived in South Africa, and besides racing together for the first time, we would also be mentoring six amateur female riders in one of the sport’s most grueling events.

When we lined up at the starting line, the reality of the undertaking hadn’t yet sunk in. A bad case of norovirus, however, definitely had. We just didn’t know it...

Words by Serena Bishop Gordon | Photos by Jeff Clark

I’m standing outside a hut at the base of the Himalaya, in a tiny village only accessible by foot, being sprayed with cow urine.

This is not how I imagined a mountain bike trip to India would go. Yet here I am, watching as the urine catches the first rays of the dewy morning light, sprinkling down like a holy golden sacrament. Which, in some ways, it is.

Back in Vancouver, BC, I would never have dreamed up such an incident, much less subject myself to it willingly. But moments like this are exactly why I’m here. Four months ago, Brandon Watts, Paris Gore, Scott Secco and I decided we wanted our next trip to take us out of our comfort zone. A place where every experience—from taxi rides to cow pee—would be different from those we’d known at home. That’s how we chose India.

Mountain bikes may have been the impetus for the trip, but the actual biking was an afterthought in our decision. Yes, we wanted to ride, but were well aware we’d likely find no perfect berms, no loam and definitely no skinny wooden ladders. We would, however, likely find plenty of culture shock, contrasts in livelihood and diverse outlooks on life. Such lofty ambitions are grandiose in theory; in reality, it turns out, they can be humbling. As the cloud of urine settled on me, I realized we’d succeeded in spectacular fashion...

Words by Micayla Gatto | Photos by Paris Gore

My obsession with Chile’s Patagonia region began in 2003, when I was given a coffee-table book titled Edge of the Earth, Corner of the Sky by a Seattle-based nature photographer named Art Wolfe.

Inside were spectacular low-light landscape photos depicting the breathtaking peaks of Los Torres and the Cuernos del Paine, located in Torres del Paine National Park...

Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994, named the fifth most beautiful place on the planet by National Geographic, and dubbed the Eighth Wonder of the World by TripAdvisor, Torres del Paine is world famous among hikers and backpackers. Two routes are particularly famous: the O and W Circuits, multi-day treks through some of the most scenic landscapes on the planet, including Los Torres, the twin granite spires that are a focal point of the park. And it sees a mere 250,000 visitors per year; in comparison, Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks see some 3.3 and 4.1 million visitors, respectively.

But beyond visitor numbers, Torres del Paine differs from the United States National Park model in one key aspect: the one that stipulates “no mechanized travel allowed.” The park’s unrivaled beauty is open to mountain bikes.

Words and Photos by Jay Goodrich

Volcanos are insane. As in, incomprehensible—for me at least.

The amount of sheer energy that lies dormant below is something I’ve only witnessed in sci-fi movies or imagined accompanying the apocalypse. But they’re also insanely beautiful.

From where I’m standing on Strawberry Mountain, I can see four volcanos and the view is slightly overwhelming. Mount Rainier is to the north, Mt. Adams toward the east, Oregon’s Mt. Hood visible to the south, and dominating the horizon to the southwest is St. Helens—or rather its leftovers. The top 1,300 feet blew off in 1980. The views from southern Washington’s Gifford Pinchot National Forest certainly don’t suck.

But I’m not here to stare at mountains, although it’s an enticing way to spend the day. Instead, I’ve got loppers in one hand and a gas can in the other. Neglected trails don’t care too much for the view, and they’re not going to clear themselves.

This mid-July weekend is one of three build parties hosted for (and by) the upcoming Trans-Cascadia. The event is a four-day backcountry enduro mountain bike race, but the ethos, operations and vision go far beyond racing. Along with putting on an epic party, organizers spend months beforehand opening and maintaining trails, quite often ones that haven’t seen footprints or tire tracks for decades. Then they send 100 people down each trail at race speeds, with the racers having zero knowledge of what’s around each corner...

Words by Jann Eberharter

When it comes to mountain biking in Switzerland, two wheels and a pair of train tracks deliver endless possibilities.

They can take you pretty much anywhere, in fact; whereas in other places, like the United States, many towns can’t be reached by train, in Switzerland many towns can only be reached by train. Much of the country is covered in mountains, and the trusty locomotives are often the only reliable means of getting around. And there’s a lot to get to: farms, hotels, lifts, entire villages—and trails, endless miles of them, braiding the ridges and valleys like a web.

The “problem” is many of these trails don’t end where they started. Of course, there’s always the option to pedal back home, but that’s often the part we want to skip. This is especially true if a trail happens to finish in a different valley, or 50 miles away.

Luckily, a train is almost always at the bottom to take you back. This pattern opens endless possibilities, from full-on singletrack DH trails to gravel-road descents. The details are different every time, and that’s the fun part...

Words by Johan Jonsson | Photos by Oskar Enander

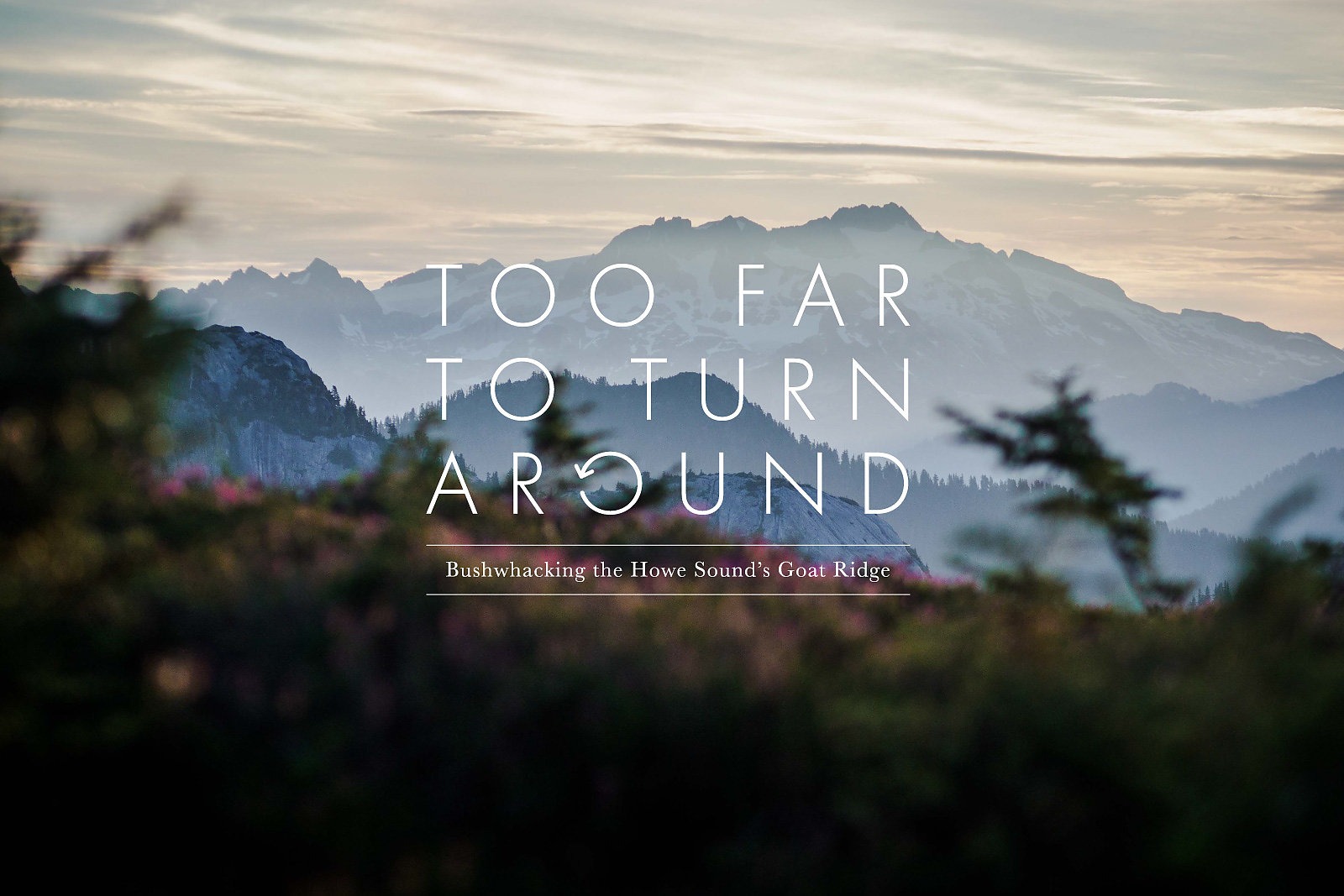

The top of the ridge was only 300 feet above, a negligible distance after shuffling along cliff edges for what seemed like miles, pushing, pulling and passing our bikes through the tangled alders.

That one vertical football field separating us from success, however, was impenetrable, impossible stone; our retreat, an alder-filled hell. With darkness climbing across the sky and no flat land in sight, one thought filled my mind: How did we get here?

Winding north from Vancouver, BC, the Sea to Sky Corridor cuts through a world of towering peaks, stretching off in all directions. The tiny town of Squamish lies at the epicenter of this terrestrial madness. Directly above is the giant granite slab known as the Chief, and a little farther beyond are the even taller bald summits of Garibaldi, Sky Pilot, Mt. Habrich and Goat Ridge. While Squamish is world-renowned for its mountain biking, this string of summits is largely the land of climbers and mountaineers.

A few months earlier, my buddy Evan Powell and I began brainstorming an ambitious backcountry loop. Starting and ending in Evan’s backyard, it would take us up to the saddle of Sky Pilot Mountain and down the entirety of Goat Ridge to Howe Sound. The problem: no trail connects Sky Pilot and Goat Ridge, a distance of less than a mile. After extensive research, and hours poring over topo maps, we determined the only way to know if the route was possible, on foot or with bikes, was to try it. We recruited two more team members, Max Schumann and Tim Wilding, and started packing...

Words by Chris Johnston | Photos by Max Schumann

I never expected to spend the last five years living out of a van, traveling around North America to ride bikes.

After eight years of university, the plan was to lead the monk-ish life of a research scientist, and at most maybe move to Europe for year and get a French girlfriend.

But then I met a drunk named Joe and a beauty named Elaine, and “the plan” went out the window in an ingenuous, chaotic fashion. Adventures, it turns out, are like that.

The detour from conventional city life came about when I was confronted with having to find a new apartment in the dizzyingly expensive Vancouver rental market. The math was challenging; on the fixed and meager income of a graduate student there was no hope in hell I could afford a new bicycle, a season of racing, a vehicle, food and an

apartment. So, I re-evaluated my priorities. Food was necessary, for obvious reasons. The racing and the bicycle were one expense, I decided, and essential for my sanity. An apartment was easily the most costly item in the equation, and also the most frivolous— but if I combined vehicle and apartment, the numbers began to make sense.

I started looking for a van I could call home. After five weeks of scouring Craigslist, I found her. Tan with an orange racing stripe, high top roof, space for bikes, and an asking price of only $5,000. I was in love...

Words and Photos by Will Cadham

Subscribe in print

or online today to continue reading!

or online today to continue reading!