Time Machines The Trails of Downieville, California Connect a Gritty Past and Pragmatic Future

Words by Sakeus Bankson

For a town of 325 citizens, Downieville, California, is home to a lot of ghosts.

They wander through the 150-year-old buildings lining the scrap of downtown; they haunt the 7,000-foot heights above, silently chipping away in the ruins of countless tunnels from one of California’s most prolific mining booms. They fish the banks of the three rivers that collide at the center of town, pulling in equally ethereal river trout. They chop and saw away at trees of primordial size, many of them destined for mine shoring, bridge abutments, or railway beds.

A decade ago, it seemed as if Downieville would become a ghost itself, rotting then fading from Northern California’s treacherous topography like so many other mining or timber towns. And it would have, if not for one spectral thread: In the Lost Sierra, the ghosts all built trails. Generations after their creators are gone, a group of passionate inhabitants are using those trails to breathe renewed life into a 300-person town that was once home to 5,000.

Born from a maxed-out credit card, a van and one chainsaw, fueled by mountain biking’s rowdiest race, and shaped by a grassroots organization’s unintentional vision, Downieville’s newest trail builders are determined to keep the town away from the afterlife by creating something that will last for generations.

“We had no imagination beyond growing the trail system,” says Greg Williams, founder and executive director of that organization, the Sierra Buttes Trail Stewardship (SBTS). “But as we started to do that, it really started to be about the people. How do we keep families here? How do we keep each other involved? That’s been the next level of the whole stewardship. The trails are the easy part.”

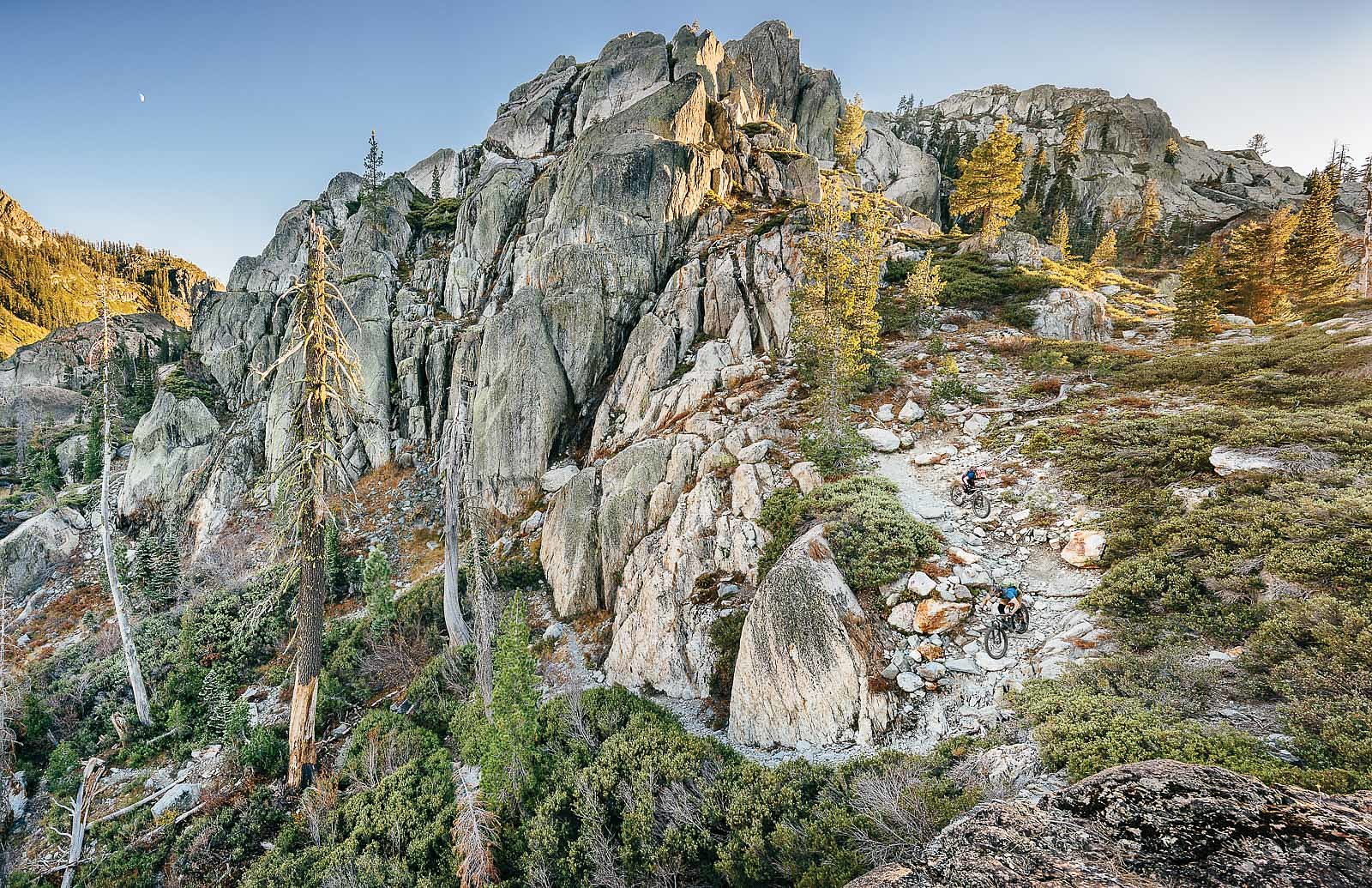

Draped across the ceiling of Northern California, the Lost Sierra makes for an impressive setting. Covering roughly 40 square miles of Plumas and Sierra counties, the region is a tangle of 8,500-foot-high granite towers, sawtooth ridgelines, alpine meadows and turquoise lakes, fissured by deep canyons. Quincy, population 1,750, marks the Lost Sierra’s north end; Graeagle, population 750, marks the east. At the south end, tucked into one of these valleys at the confluence of the Downie and North Yuba rivers, is the tiny town of Downieville.

It’s a stunning place to visit, one of the reasons it’s become hallowed ground for mountain bikers and outdoor recreationalists. It’s also a really dumb place to start a town. The narrow valley has very little level ground, limited space for infrastructure, and would be a death trap during a wildfire.

“The only reason we’re here is because of one word, and that word is ‘gold,’” says Lee Adams, Downieville resident, former sheriff and district supervisor of the Sierra County Sheriff, and member of the State Historical Resources Commission.

In the mid-1800s, that was a powerful word, especially in California. The precious metal was discovered in these same mountains in 1849, and kicked off one of the biggest gold rushes in history. Countless would-be millionaires swarmed the Lost Sierra, and a rash of makeshift towns sprung up wherever it was flat enough for a tent and a road.

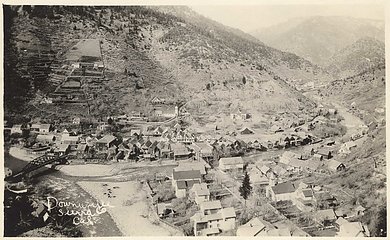

By the 1850s, Downieville was the largest town in the Lost Sierra and one of the richest in California, with amenities that put modern Downieville to shame. An estimated 2,500 to 5,000 people lived within five miles of downtown, funding a dozen hotels

and saloons, a barbershop, bathhouse, multiple grocery stores, a cigar shop, a candy manufacturer, an express mail office, a surgeon/dentist, and no fewer than four doctors. “In 1853, it was one of 16 communities running to be state capital,” Adams says. “It came in ninth, but Los Angeles was not even one of the 16.”

Such an explosion of humanity came with costs, the miners’ standard of living being one of them. Supplies were incredibly expensive, especially in winter, and even tent space was hard to come by. But the landscape paid the dearest price—the surrounding hillsides were stripped bare of trees and vegetation, cut down for building homes, railroad ties, firewood, shoring inside the mines, or simply to make access easier. Plumbing was limited at best, and the gritty miners used the river for bathing, drinking and other less savory ablutions.

The population of Sierra County topped out at 16,000 people that same year, but it’s hard to build a sustainable town when you’re actively removing the resources that allow it to exist. The arrival of hydraulic mining sped up that process; the method involves literally blowing away the hillsides with hoses, and nowhere was the practice more common than in the Downieville area.

“They were blasting so much away that downstream towns like Marysville were being completely buried in mudslides 20 feet deep,” says writer Mike Ferrentino, author of Bike magazine’s longtime column, “The Grimy Handshake,” and a founding member of SBTS.

This motivated the California legislature to make hydraulic mining illegal in 1884, and—along with falling markets and the arrival of the first and second World Wars—the Lost Sierra’s golden glory days ground to a halt. Forestry, however, was still thriving in Sierra and Plumas counties, and towns like Graeagle, Williams’ current hometown, saw booms akin to the mining days. Downieville becamse home to the United States Forest Service’s district office, which supported as many as 50 full-time employees and even more seasonal workers.

But those numbers dwindled with each government funding cut, and the logging industry was squeezed by new environmental laws, until in 1980 the USFS decided to move the district ranger office to Nevada City, California. Fifteen years later, the Lost Sierra was one of few places in California where the population was shrinking. The ghosts, however, weren’t going anywhere.

Some of Williams’ best childhood memories come from the Lost Sierra of the 1970s, although the Nevada City native’s roots reach even deeper than the area’s glory days. His great-great grandfather, a member of the Miwok tribe in Nevada City, moved to Downieville during the Gold Rush to lead pack mules into the remote mines. Williams remembers summer vacations spent driving the Lost Sierra’s old 4x4 roads with his parents in their 1942 Jeep. “Where my dad got stuck was usually where we camped,” he says. “One time we got stuck in a spot for two weeks before somebody helped haul us out.”

Both bikes and business have been key parts of the 47-year-old Williams’ history as well. He raced BMX from an early age, and in fifth grade got in trouble for selling bubble gum to his classmates to fund new bike parts. Looking to keep him out of trouble, when Williams turned 17 his parents bought him a mountain bike—which, in turn, brought him back to Downieville.

“The first time I rode from town was 26 miles of pavement with 5,000 feet of ascending,” he says. “I figured, ‘Shit, people would love to get a shuttle to the top of this hill.’ That started working its way into my brain. I knew bikes were important, I knew this place was important, but I didn’t know how to put it together. As soon as I knew, man, I just poured everything I had into it.”

“The first time I rode from town was 26 miles of pavement with 5,000 feet of ascending. I figured, ‘Shit, people would love to get a shuttle to the top of this hill.’ That started working its way into my brain."—Greg Williams

For Williams, that “everything” consisted of a van and roof rack, which he bought in 1992 after being approved for a $10,000 credit card. He called his new business the Coyote Adventure Company and began driving customers from Nevada City to ride the huge descents around Downieville. Armed with Gold-Rush-era maps and a lot of free time, he set out to explore even more of the Lost Sierra—for better or worse.

“In the early days we just tried to get down the hill, keep our bikes together and keep ourselves together,” he says. “It was fun, but it was also kind of a survival experience.”

With a van and some go-to routes, in 1993, Williams moved his operation to Downieville—or, rather, he posted a clipboard outside a pizza shop where people could sign up for shuttle rides. It was successful enough that by 1994 he could afford rent: a 10-by-10- foot space in that same pizza shop, which also served as his bedroom.

Downieville doesn’t have many easy riding options, so there were frightening moments, but visitors routinely left wanting to return. Hoping to draw more riders to the area, in 1995, Williams decided to put on an event as oddball and ambitious as the Lost Sierra: the Coyote Classic, a point-to-point, National Off- Road Bicycle Association-certified race from Sierra City to Downieville.

“There’s nothing like a stopwatch and a timed run for people to really pay attention,” he says. “We didn’t even have a timer—we just figured the guy from NORBA would have it covered. My wife Heather, who was my girlfriend at the time, handled registration, and we slept in the middle of a dirt road with my parents. Looking back, we had no idea what the fuck we were doing.”

People loved it. That first year 277 riders showed up, and a news clip from the second year shows a field of Lycra-clad competitors on fully rigid bikes, bumping their way into town with smiles as big as they are dirty. In place of prize money, early winners were given a gold nugget, pulled straight from the Yuba River.

That success turned bitter in 1998, when Williams’ financial partner sued him for the rights to the race. The ensuing two-year legal battle drove Williams into bankruptcy, but he kept the renamed Downieville Classic and Yuba Expeditions alive with the help of the area’s ever-growing tribe; folks like Debbie and Chuck Bonovich—Downieville regulars since 1992—who took over managing an ever-increasing number of volunteers, and Marc Cosbey, a former crew hand on America’s Cup sailboats and caretaker at the Gold Lake Lodge in nearby Lakes Basin, who took over handling the course.

“That was probably the first year that I really realized how important people are in your life,” Williams says. “Those two years I was in court on the Friday before the race, battling an injunction to keep it going. If I lost, if the race would’ve stopped, I would’ve been back in bankruptcy. Downieville would’ve stopped. Those people stepped up and made it happen.”

As far as races go, the Classic is unique for both organizers and participants. Dropping more than 5,000 vertical feet in 15 miles, the downhill race is the longest in the United States; that number, however, also includes more than 1,000 feet of climbing. Inversely, while the cross-country race climbs some 4,500 vertical feet over 26.5 miles, it also includes 5,700 vertical feet of descending. The hefty numbers ground down even world-class professionals, who were used to downhill or cross-country-specific courses. But others excelled in the brutal variety, including iconic freerider Mark Weir. Now known for his all-around style and tenacity (and massive Fu Manchu moustache), “Mr. Tough Guy” raced the sport category during his first Classic. He would go on to win the downhill eight times.

“Mark Weir was instrumental in making Downieville a thing,” Cosbey says. “He brought it to the forefront. The way he approached it, the way he trained for it, the mentality that he had. He would come out a few months early, help me prep the course because he wanted to know every inch. He would look at lines, practice them while we were out there. And then come race day he was the Muhammad Ali of Downieville.”

Weir wasn’t the only suffer-fiend, as attested by the popularity of the “All-Mountain” category. Introduced in 2005, the event requires riders to race both the downhill and the cross-country events on the same bike. Of the 2018 Classic’s 800 total participants, nearly 350 people competed in the all-mountain.

“If someone underestimates the Classic, they’re stupid because it’s the hardest race you’ll ever do,” Weir says. “We’ve heard grown men cry like babies.”

The course’s infamy is offset by the goofy, wild and unconventional in-town antics. Throughout its nearly 20-year history, it’s come to include a river jump (dubbed Ron’s Big Air, in honor of Williams’ father, who came up with the idea), a log pull down Main Street, Cosmo’s Wild Island competition (in which cyclists ride out a rickety, inner-tube-supported gangway to an inflatable island in the river), raffles, beer gardens, gear expos, dance parties and even a breakdance competition—all made possible by the efforts of 200 volunteers, many of whom have been attending since the event’s early years and now bring their families.

“The Classic is really the tribe-builder of the whole thing,” Williams says. “It’s a bunch of anarchy. Then right around 5:00 on Sunday the lights go off, and we take town back over. Come Monday morning, I’m out sweeping the streets and getting town cleaned up for the locals.”

His DNA may not be connected to the area, but for Mike Ferrentino the Lost Sierra has felt like home ever since he moved to Nevada City in 2000. Shortly after, Williams hired him as a mechanic at the shop in Downieville. Two years later, Ferrentino was living in Downieville, walking through the woods with Williams commiserating about the winter.

It had been a heavy snow year, meaning there would likely be an equally heavy number of trees blocking the trails come spring. They’d called the local USFS office to ask about getting them cleared, but the cash-strapped agency didn’t have a sawyer on staff. So, the two asked a different question: What if they did it themselves?

The USFS took no issue with their tree-clearing plan, so Ferrentino, Williams and Cosbey bought a chainsaw and headed into the mountains. The result was a “comical crash course in how to run a chainsaw,” Ferrentino says. “We weren’t very good. We probably shouldn’t have had one.”

Instead, they bought two chainsaws (they bought the second to cut out the first after getting it stuck in a downed log) and began thinking about what they could accomplish with even more people. It was a shared sentiment; their first trail work days drew 20 people, then 30, then 40 or more, all coming to work, ride bikes, drink beer and “howl at the moon,” Williams says. “Those work days got to be a really big thing.”

In 2004—with the help of Carl Butz, an “IT tech guy who lives off the grid”—the group established a nonprofit, and began to help clear, build and maintain the trails upon which the Classic and Yuba Expeditions depended. The Classic itself, however, took a break; that year Greg and Heather had their first child, Kenzy, and between that and starting the nonprofit the crew decided to postpone the race.

“You can’t just go somewhere and take; you have to put back in,” Ferrentino says. “So the idea of the stewardship to me was, ‘We owe it to these trails, to this community, to take care of this stuff we’re making a living off of.’ I think even at that point Greg was already arching several steps further along.”

By the early 2000s, Plumas and Sierra counties had fallen from two of the richest in California to two of its poorest, and two of only three in the state with shrinking populations. Many of those who remained in Downieville and the surrounding communities saw mountain biking as a challenge to their heritage.

“There’s a resistance you’re going to have to overcome, that whatever you’re doing isn’t as valid or is somehow disrespectful to the reason those families lived there for generations,” Ferrentino says. “So, you invest yourself fully. You stake your place with your family, and you say, ‘I’m going to continue to do this because I think this matters. This place matters.’”

As the nonprofit’s founders quickly found out, far more people cared about this community than anyone expected. By that time, the Classic and Yuba Expeditions were doing well enough that Williams could fund a trail crew. But great vision requires greater resources, so the group decided to apply for some grants. They just needed a name.

“We were all about the trails, then came this grant application with ‘stewardship’ in it,” Williams says. “It was like, ‘Sierra Buttes—that’s our mothership. That’s gotta be it.’ From there it all just fell into place.

“In hindsight, that we didn’t name it ‘Downieville Mountain Bike Organization’ was the key to everything. It was the gateway. We’re a trail stewardship, and we’re all-inclusive. We all hike, we ride mountain bikes, we ride dirt bikes. Some of us ride horses. We’re all about everybody being out in the forest.”

Intentional or not, that inclusive ethos came to define the SBTS. In the past 15 years, they’ve worked on mountain bike trails, dirt bike trails and ADA-accessible pathways; they’ve also worked on wilderness trails and 70-plus miles of the Pacific Crest Trail, all of which are permanently closed to bikes. Closing out 2018, their resume includes a total of 101 trail projects, including building 84.4 miles of new trail and maintaining 944 miles of existing trail, completed with the help of 1,342 volunteers who put in 85,000 hours of labor.

These numbers are reflected in the local economy as well. More than 10,000 people visit Yuba Expeditions every year, and each season they run more than 7,000 shuttles. The Classic’s success has since spawned two other races—the Lost and Found Gravel Grinder and the Grinduro—and Williams estimates the three events have had a $10 million impact on the Lost Sierra. In 2018, the race, the shop and the adventure company earned $2 million in gross income, all of which goes back to the Stewardship and into the community. Last year, $856,000 supplemented the salaries of their 46 fulltime-employees, nearly all of which live in either Plumas or Sierra counties.

“Visitors are great,” Williams says, “but if you don’t have people here to interact with them, if you don’t have kids in the schools, you start to lose a sense of community. We feel recreation can be a mechanism to attract the kind of people who want to be stewards of the land, and also have a sense of pride for where they live.

"Visitors are great, but if you don’t have people here to interact with them, if you don’t have kids in the schools, you start to lose a sense of community. We feel recreation can be a mechanism to attract the kind of people who want to be stewards of the land."—Greg Williams

“Then we’ll be able to get more kids in the schools and teach them how to take care of this place so when we’re gone, we know it’s in good hands.”

Initially, Cosbey managed these volunteers as trail crew boss. But the current boss, Henry O’Donnell, is an example of that dream made reality. O’Donnell was born and raised in Downieville and began working at the Yuba shop when he was 10 years old, earning five cents for every fly he swatted until he was promoted to cleaning the vans. At age 15, O’Donnell won the Downieville Downhill, beating out a field of world-class pros.

He’s since ridden around the globe for Santa Cruz Bicycles, but he’s always called Downieville home—as do his children, Levi and Logan. Thanks to SBTS’s high-school trail crews, they can start their bike careers with shovels instead of fly swatters—the program employs 13 students each summer, and has provided jobs for more than 100 local kids since its inception in 2011.

Characteristically, SBTS’s newest effort is about unconventional stewardship. In 2018, they started a new branch called Lost Sierra Development, which buys properties in the area to ensure locals have reasonably priced housing options.

“We think it’s going to change people’s lives,” Williams says. “In a lot of mountain towns, all the available housing goes to VRBOs and Airbnbs, and people in the service industry can’t afford to live there. Downieville is a spot where we feel like we can make a difference, where we can provide housing and opportunities for them to thrive.”

It’s an ambitious effort, the results of which will take decades to fully be seen. In the meantime, Williams pulls motivation from those projects that have already matured.

“The one that probably stands out the most to me was building the North Yuba River Trail,” Williams says. “It was seven miles and all hand-dug, and it took us 13 years. The progression of things that happened on that trail, to watch people grow up and to watch the town change, to watch my life change—it’s like a time machine.”

Downieville may be SBTS’s home, but there’s a reason it’s named after the Sierra Buttes. As locals know, the legacy of the Lost Sierra’s ghosts extends far beyond the Downieville Classic. The Stewardship’s master plan includes using old 4x4 roads and miner paths to connect Quincy, Graeagle and Downieville with a trail network stretching dozens of miles.

Part of that effort is Mills Peak, a nine-mile, 3,000- foot alpine ride that was funded with a combination of grants and $36,000 in donations. Another is the Tower 2 Town trail, an 18-mile, 7,000-vertical-foot descent from the summit of the Sierra Buttes to Downieville that is one of the longest in North America. And those are just the newest—the area has as many local classics as it has ghost towns.

“If the race is their sole experience with Downieville, that’s an awesome thing,” Ferrentino says. “But it is just the corner of what is out there, and the further you get from the racecourses, the more you get into this just spectacular high-country riding.”

Beautiful and challenging may make for incredible riding, but it still begs the question: What made Downieville, just one of dozens of boom-and-bust towns in the Sierras, a mountain bike mecca? For Williams, it’s the inhabitants and their unrelenting tenacity to stay in a place they love, be they spandex-clad mountain bikers, old loggers in cutoff AC/DC shirts or the ghosts who haunt the room above the pizza shop.

“Really, the power of the stewardship is those relationships,” Williams says. “People will do a lot of things for people they care about. That’s what makes it all happen, that’s what makes this tribe. That’s what makes dirt magic, and everything we do possible, is just the relationships and people’s passion.”

![“Brett Rheeder’s front flip off the start drop at Crankworx in 2019 was sure impressive but also a lead up to a first-ever windshield wiper in competition,” said photographer Paris Gore. “Although Emil [Johansson] took the win, Brett was on a roll of a year and took the overall FMB World Championship win. I just remember at the time some of these tricks were still so new to competition—it was mind-blowing to witness.” Photo: Paris Gore | 2019](https://freehub.com/sites/freehub/files/styles/grid_teaser/public/articles/Decades_in_the_Making_Opener.jpg)