Time Flies Past is Present for Jonnie Benda

Words by Kurt Gensheimer | Photos by Ryan Salm

Jonnie Benda is a man of simple means, as evidenced by his beaming smile and infectious laugh. He’s not burdened by societal distractions such as the internet, social media, or even a cell phone; none of these have played a role in his life. Benda’s lack of connection to the digital world has insulated him from the daily doom and gloom fed to the masses. He is the embodiment of a happy-go-lucky human.

If you want to talk with Benda, you have to go old school: call his landline and leave a message “at the beep” because he’s most likely out working, skiing, riding or digging. He drives a 20-year-old Toyota pickup and has held the same job as a waiter at the Resort at Squaw Creek, in Lake Tahoe, California, for 30 years. His wardrobe dates back to the same era, sporting a threadbare Calvin Klein long-sleeve riding jersey, Oakley baggies and worn-out work gloves with his thumb protruding from the side. He has newer clothes he could wear, but according to Benda, he doesn’t want to look too “factory fresh.” When it comes to living life, Benda is about as grassroots as it gets.

If he’s not at his job serving food and chatting with visitors on their ski vacations, Benda’s at play somewhere in Coldstream Canyon, making mountain bikers smile while enjoying Truckee, California’s most popular trail network, lovingly known as Yogi Bear. But of the thousands of riders on Yogi Bear’s perfect berms, small gap jumps, techy rock features and colorful trailside attractions, nobody’s smile is brighter than Benda’s. Riders who bump into him on the trails would never know that Benda is the curator of this unique riding experience; his humility is equal to his stoke for seeing others having fun.

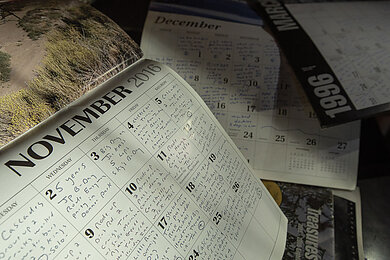

For exactly 30 years, Benda has moved dirt in Coldstream Canyon, a short bike ride from his Armstrong Tract home overlooking Donner Lake. If the trails aren’t proof enough of Benda’s three decades of labor, his collection of 30 years’ worth of calendars is. In them, he’s meticulously noted every single day he’s worked on a trail, specifying its name and who joined him. Each calendar is like a CliffsNotes diary of a life well-lived. Equally impressive as his documentation, Benda’s memory of each long-since-past day is as vivid as if it happened just yesterday. Scanning through his impressive collection is tantamount to deciphering a code. One particular entry simply states, “Oink oink all day.”

“Powder pigs!” Benda explains. “Skied pow all day on that day!”

Some people mistakenly think Benda’s name is Jonnie Patrick, due to the iconic JP trail he helped to build in Coldstream Canyon. In actual fact, the trail name’s initials refer to Benda’s first name as well as the first name of the close friend who helped him complete it, Patrick Kennedy (i.e., the Jonnie and Patrick trail). The 30th anniversary of the trail’s completion was on November 6, 2021, and despite pouring rain and cold temperatures Benda, his longtime lady Chris Kelly and a couple of friends still went out for an hour-long celebration ride.

Benda first arrived in Truckee in 1990 along with a friend from his teenage stomping grounds of Temecula, California, trading in his skate park and BMX upbringing for a ski bum lifestyle. A year later, his buddy went back south, but Benda stayed. He loved the mountains, yet there was one problem: Truckee had no good mountain bike trails.

When Benda first started working at the Resort at Squaw Creek, he met Patrick Kennedy, also known as “PK Tripper,” a chef at the time and a fellow mountain biker. They became fast friends through PK teaching Benda how to be a powder pig. The resort was also where Benda and his partner Chris met. They started dating on September 11, 2001, during a trailwork day on JP trail. He also met his longtime digging partners, Rob Holodinksi (aka Hodo) and Joel Severy, while working at the resort.

“Pretty much all my old friends can be linked back to working at the resort,” Benda says.

The construction of JP was entirely autodidactic. Besides building a couple of rudimentary tracks as a 10-year-old kid on his parents’ 12-acre ranch in Nebraska, and some dirt jumps as a teenager in Temecula, Benda had never built a proper mountain bike trail.

“The original JP trail was really steep because we didn’t know any better,” Benda says. “We modeled it after the Pacific Crest Trail because that was the only trail around back in that day. Then one day, I saw a deer running up a game trail and realized that animals are really good trailbuilders. We then incorporated the game trail into JP.”

Because JP was an unsanctioned trail, Benda, PK and a small circle of builders kept a low profile, only digging a couple of days per week after work to avoid being spotted by rangers. The first few years were spent mowing through vast fields of manzanita bushes on the south shoulder of Schallenberger Ridge with nothing more than pruning loppers and handsaws.

The work went slowly, but Benda and PK were undeterred, taking a long-game approach to trailbuilding. According to his calendars, it took Benda, PK and other friends 13 years to build only 3.5 miles of JP.

Part of the reason why JP took more than a decade to build was due to the damage incurred during the fateful winter of 1997, when a historic rain fell on several feet of January snowpack, creating catastrophic flooding across the region. The wake of that storm taught Benda everything he needed to know about drainage, as more than half of the corners on JP were completely blown up, forcing him to reconstruct much of the trail.

Once JP was finally completed in 2004, another one of Benda’s trailbuilding partners, Dan Goddard, turned him on to a new zone away from the sea of manzanita on Coldstream Canyon’s south-facing side.

“We used to sit at the top of JP trail looking out over Coldstream and across to the other side and dream about someday having a loop that would go around the entire canyon,” Goddard says.

Goddard is an avid backcountry skier and knew the canyon’s north-facing side well. This loamier side of Coldstream would eventually connect with JP for a giant 20-mile loop around the canyon, split down the middle by the massive, horseshoe-shaped switchback of the Union Pacific Railroad approaching Donner Summit.

“Truckee is blessed with a handful of community builders like Jonnie. They are artists, each with their own style of building that makes for totally different riding experiences."

— Matt Chappel

After JP was finished, word got out and riders arrived by the hundreds. The sudden increase in traffic prompted Goddard to start building a new trail on what was then called Jackass Ridge, a promising zone just above Highway 89 that the U.S. Forest Service’s Truckee Ranger District has recently renamed as Donkey Town. This new terrain would become the site of one of the builders’ finest trails, Yogi Bear. According to Benda’s calendar, he and Goddard started working on the trail in the summer of 2005, with Benda flagging the alignment and Goddard getting busy with his chainsaw. The work progressed much more quickly than with JP, averaging a mile of new trail per season. Things were going smoothly until it came time to name the trail.

“Every time I drove up the dirt road past the town dump on my way to the worksite, I’d see these giant bears raiding the dumpsters getting all fat and stuff, so I wanted to call the trail Yogi Bear,” Benda says. “Dan didn’t like it.”

Goddard agrees that he initially opposed the name.

“I fought it at first because I didn’t want it to be cartoon land,” Goddard says, “but I soon realized it was a great name.”

Seventeen years later, Yogi Bear has been transformed into a 17-mile-long network featuring trail names like Boo Boo’s Revenge, Snagglepuss, Honk Kong Phooey, Jellystone Jump and another Hanna-Barbera cartoon character, Captain Caveman. Hidden among the trees is an ammo box filled with dioramas of figurine characters from the Yogi Bear cartoon series.

Linking the Yogi Bear network to the trails on what used to be called Jackass Ridge, Captain Caveman is a connector recently built by Benda and the Truckee Dirt Union (TDU) that has been formally adopted by the U.S. Forest Service. In addition, the Forest Service has sanctioned the recently renamed Donkey Town trail as well as another trail that was recently completed by the Truckee Trails Foundation and renamed from A1 to the El Burro trail. Benda has been heavily involved with the transformation of the trails in this zone since 2010, refining them with jumps, berms and rock features.

“He literally took a broom to the corners, and we gave him a hard time about it, but there was no denying he made the trails amazing,” Goddard says.

No place in the Lake Tahoe area returns more smiles per foot climbed than the Donkey Town trail. Thirty minutes of mellow climbing delivers almost as much time descending, with berms, gaps, tabletops and drops, all of which feature roll-arounds to make the trail safe for riders of all skill levels. The proof of its popularity is in the parking area along Highway 89, where it’s hard to find a single spot, even on a weekday afternoon.

Donkey Town has become such a sensation that some feel it’s even eclipsed the popularity of icons such as South Lake Tahoe’s legendary Corral Trail. In the summer of 2021, the TDU collaborated with the Forest Service to track the number of weekly laps on Donkey Town.

“We tracked several thousands of users each week during peak-season times,” says TDU co-founder Matt Chappell.

The surge in popularity of the Donkey Town and Yogi Bear networks is largely because the trails appeal to a wide range of riders, all the way from beginners to experts. Every trail can be climbed in either direction while still being steep enough on the downhill for Zen-like flow. Everything has a harmonious symmetry; corners link seamlessly with perfectly crafted berms, and even the gap jumps instill confidence that one won’t come up short on the backsides. There are options everywhere, from small rock drops to bigger lines up and over granite boulders the size of storage sheds. All of this joy stems from Benda’s “singletrack radness” philosophy, which he explains as simply using the terrain that Mother Nature has provided to shape an unforgettable riding experience.

Though Benda’s trailbuilding creativity has helped to put Truckee on the map as a world-class riding destination, the fact that many of the trails run through a mix of federal, state and private land makes their status uncertain. This uncertainty prompted longtime locals such as Chappell, Skye Allsop and Greg Forsyth to form the TDU in 2020, mostly to foster volunteerism among the local mountain bike community. The effort has paid off in spades, with increasing numbers of newer riders working with dedicated builders like Benda for a mutually beneficial path forward.

“Jonnie’s efforts over the years have given rise to the mountain bike culture here in Truckee,” Chappell says. “With so many new people moving to town, we want to preserve and protect our culture of ‘singletrack radness’ through getting families and friends out on the trails, not just with their bikes, but also with tools to help maintain and connect with the trails.”

Another vital function of the TDU is to voice the needs of the trailbuilding community to city, county and federal land managers.

“Guys like Jonnie keep a low profile and don’t have any desire to sit in meetings,” Chappell says. “Truckee is blessed with a handful of community builders like Jonnie. They are artists, each with their own style of building that makes for totally different riding experiences. The TDU is representing trail artists and organizing a 400-person volunteer workforce to create positive outcomes for mountain biking in Truckee.”

The decades of blood, sweat and tears shed by Benda to build world-class trail networks have brought much-needed tourism dollars to Truckee, but still almost half of the town’s trails have yet to be officially sanctioned. Given this, Chappell and the TDU are focused on making sure that Benda and other builders can continue to legally practice their art and even get paid to do it, working above-thebar in collaboration with landowners.

Truckee has a long history dating back to the 1860s, but the town was only legally incorporated in 1993, making it relatively young as a municipality. Yet with the recent influx of new full-time residents—many of whom are dedicated mountain bikers—the town’s demographics are shifting and there is increased support and funding for legal trails. With this in mind, Chappell now sees more opportunity for the TDU to create a shared, grassroots vision between community trailbuilders and many of the new trail user groups.

“The TDU is focused on helping create and complete multi-use trail projects, but we are mountain bikers first,” Chappell says. “We ask, ‘what can we do to help?’ and are getting things done creatively without having to ask people for money. Mountain bikers in Truckee are realizing that if they show up to do the work, they can help create the trails they want to experience.”

For Benda, Coldstream Canyon holds much more than the nearly 30 miles of “singletrack radness.” It holds the last 30 years of his life. It holds all of his memories with friends, volunteers, and his partner Chris and their dogs, Chester and Tundra—who joined him on every single trail day, chasing after porcupines and receiving a face full of quills. Both dogs are buried along the lower Yogi Bear trail in commemoration of their lives spent with Benda in Coldstream Canyon.

Despite the surging popularity of the Truckee trails—thanks in large part to social media and the many YouTubers who’ve documented their Donkey Town riding experiences—Benda hasn’t become jaded in the slightest. During a TDU trailwork day in the fall of 2021, he counted more than 100 riders in a three-hour period on a Friday afternoon. Benda smiled and shouted words of encouragement to every passing rider, and he knew the names of at least a quarter of them.

Goddard sees Benda as an inspiration to many riders and wishes others could be as considerate as him. Goddard recalls a time when he found a fallen but movable tree in the middle of a trail, with numerous tire tracks skirting the obstacle.

“Why someone doesn’t just move the tree is beyond me,” Goddard says. “But when they see all the work Jonnie puts into the trails it inspires them to lend a hand. Plus, he’s just a super simple guy who follows his own set of rules; a big kid who never takes things too seriously.”

The simplicity of Benda’s life might be as inspiring as the “singletrack radness” he curates. But amid the ubiquity of social media and the rush of Silicon Valley remote workers who have moved to Truckee, it remains to be seen whether he’ll be dragged into the digital dependencies of the 21st Century. One test came in December 2021, when a record-breaking storm dumped eight feet of snow on Benda’s house, severing his only form of communication—the telephone landline—for almost a month.

“I don’t know, man. I think AT&T is trying to force me to cave in and finally get a cell phone,” Benda jokes.

Of all the cultural threats Truckee now faces, Benda’s forced adoption of a cell phone might be the most pivotal.