The Testing Grounds Trails Reshape Communities in Northwest Arkansas

Words by Jess Daddio

Bea Apple never considered herself an active kid. And yet, when she and her family moved from the Bronx to Rogers, Arkansas, back in 1993, then 13-year-old Apple couldn’t help but feel the pull of the Ozark region. Its wide-open plateaus and deep, forested valleys, its sandstone bluffs cut by clear waters, begged to be roamed. The Natural State was green and vast—nothing like the home she had previously known.

Apple’s family had emigrated from South Korea to the United States in the ‘70s. When they first landed in Northwest Arkansas (NWA), they found community with a local Korean church. Apple’s first camping trips in the Ozarks were with that church group. They’d spend weekends at Hobbs State Park-Conservation Area and Beaver Lake, just outside of Rogers.

Back then, Hobbs had none of the modern, bike-optimized Monument Trails that Arkansas’ state parks have become known for today. There was no bike park in Apple’s hometown of Rogers, no trails tying Bentonville’s neighbors together with backyard ribbons of dirt. Prayers and poultry plants sustained life in much of the Ozarks. Throughout the ‘90s and early 2000s, NWA—a region centered around the cities of Bentonville, Fayetteville, Springdale, and Rogers— depended on manufacturing, transportation, and agriculture to keep the lights on. Mountain biking existed in the area, but only at the fringes. Tourism as a whole was still in its infancy. If there was one thing the region was known for, it was Walmart, which started as the Walton’s 5&10 (five-and-dime) in Bentonville, just seven miles northwest of Rogers.

For years, there had been little change in NWA. Life was quiet, the cost of living affordable, and the population mostly working class. But more than a decade after Apple moved to the Ozarks, the Walton family’s outdoor-loving grandsons, Tom and Steuart, began investing their Walmart fortune into Bentonville, building it into the self-proclaimed “Mountain Biking Capital of the World,” and sweeping the entire region into a metamorphosis of fairy tale proportions.

Apple moved to Bentonville in 2006, one year before the city opened the first five miles of Walton-funded trail at Slaughter Pen. By then, she had lived and traveled all over Arkansas. Over the years, she had heard about people mountain biking, but, she says, she thought the sport was “extreme with a big ol’ X.”

An electrical engineer-turned-entrepreneur, Apple found she had a knack for hospitality. In 2011, she opened the restaurant Pressroom and made fast friends with her neighbors at Phat Tire Bike Shop. As the Slaughter Pen trail system grew, along with Bentonville’s reputation as a cycling destination, Apple, her family, and her business were swept up in the movement. Pressroom’s location made it a go-to post-ride spot for cyclists. The restaurant even sponsored a road team. When Apple had kids, she put both of them on Striders.

Meanwhile, it seemed that new riding spots were cropping up every month: the Rogers Railyard Bike Park and Lake Atalanta trail system; Bella Vista’s Little Sugar, Back 40, and Blowing Springs trail systems; and a new skills course and loop around Lake Fayetteville. In 2014 and 2018, the International Mountain Bicycling Association (IMBA) awarded Fayetteville and Bentonville bronze and silver-level status, respectively, as IMBA Ride Centers, creating the first-ever IMBA Regional Ride Center.

In 2016, the mountain bike momentum in the region was so palpable that IMBA decided to host its World Summit in Bentonville. That same year, Apple finally went on her first mountain bike ride. A friend gave her a used carbon mountain bike. She was so excited to ride it, she bombed down All-American—a one-mile flow trail that starts downtown—without her helmet. On her next ride, helmeted this time, she followed her friends Kim and Jordan out to the Tatamagouche and Medusa trails in Slaughter Pen. It was illuminating.

“That was my first experience of having your brain blown open by riding with other people and how fun that is,” she says. “It was just magic. Mountain biking transformed my relationship to the outdoors, to this place, to Arkansas.”

At 36 years old, Apple dove headfirst into the fast-growing mountain bike scene. Her kids did, too. They learned together. She started coaching for her oldest son’s National Interscholastic Cycling Association (NICA) league. She saw firsthand all of the unique opportunities kids like hers had to ride trails right from their front doors, to plug into a community that was truly inviting to riders of all ages and abilities. It was everything Apple wished she’d had access to as a kid. But as Bentonville and the surrounding communities continued to churn out an unprecedented two to three miles of new singletrack per week, Apple’s property taxes doubled, tripled, and eventually quadrupled. As much as she loved to ride and to see her kids ride, Apple started having concerns about trail access and equity.

“I was exposed to all of the super positive aspects of [mountain biking], especially from the youth sports and community building perspectives,” she says, “but at this point a lot of regular middle-class folks are totally priced out of even owning a house in Bentonville, so what does that mean about who the trails are for? There are pros and cons for sure.”

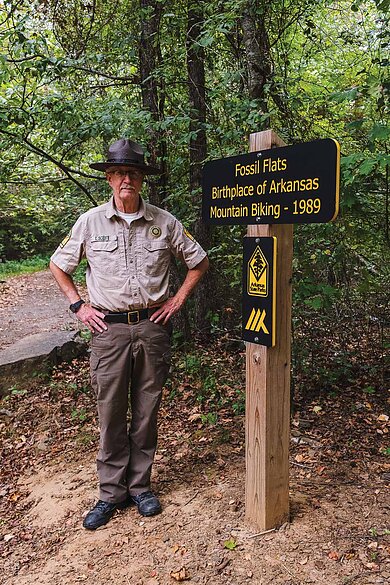

Devil’s Den State Park Assistant Superintendent Tim Scott knew this day would come. A Natural State man at heart, Scott had laid the groundwork for the region’s mountain bike scene long before the Waltons got involved. Locally he’s known as the Godfather of Arkansas Mountain Biking. Scott was born and raised in Rogers, went to college at the University of Arkansas, and got his first job at a state park east of Little Rock in 1978. In 1984, he returned to NWA to work for Devil’s Den, a CCC-built state park in the Boston Mountains, 30 miles south of Fayetteville.

"MOUNTAIN BIKING TRANSFORMED MY RELATIONSHIP TO THE OUTDOORS, TO THIS PLACE, TO ARKANSAS.”

—Bea Apple

A year later, Scott noticed some mountain bikers were visiting the park to ride its hiking trails and old roadbeds. At that time, many land managers elsewhere were banning mountain bikers from riding in their parks, but Scott and his supervisor, Wally Scherrey, rode bikes. They wanted to foster mountain biking in Arkansas’ state parks. They just didn’t know how.

In September 1988, Scott and Scherrey packed their mountain bikes and camping gear into a Devil’s Den housekeeping van. They drove to Crested Butte, Colorado, to attend the town’s Fat Tire Bike Week festival in the name of research. Scott approached the bike festival like the parks scholar he was and took detailed notes of everything from mountain bike slalom to log-pulling contests. In his mind, Devil’s Den had all of the ingredients to host a similar event; he just had to convince his higher-ups that it was feasible.

“At this point, we [Devil’s Den] are beginning to get some bikers,” Scott wrote to senior park officials in his post-trip memo. “The question is do we want to invite these folks, to actively seek their business or to wait until they appear in great numbers. No matter which route we take they are going to come. This is assuming that this ‘fad’ does not pass Arkansas altogether, which I feel it will not. In fact, the whole park system should be prepared.”

His prediction proved persuasive. In 1989, Scott organized the Ozark Mountain Bike Festival in April and the NWA Mountain Bike Championships in September. Both were largely considered the first of their kind in the state. The festival featured many of the activities Scott had seen in Crested Butte, such as bike trials and that log-pulling contest. More than 100 racers toed the line for the September cross-country race, which looped out of the park onto Forest Service roads in the Ozark National Forest.

The events were so successful that the state park gave Scott the green light to not only continue hosting them— which he has every year since, with the exception of 2020— but also to build a trail at Devil’s Den for the express purpose of mountain biking. Over the course of the next year, Scott spent months hand digging that trail, paralleling Lee Creek’s exposed and fossil-studded limestone bed. The three-mile loop, which he named the Fossil Flats trail, made its debut at the 1990 festival. Many still consider it the first mountain bike trail in Arkansas.

“Believe it or not, yeah, there was mountain biking before Tom and Steuart Walton,” says Ozark Off Road Cyclists (OORC) President Rob Reno.

Reno moved to the region in the mid ‘90s. The OORC was founded in 1997, but the volunteer trail advocacy and maintenance organization was loose and informal. Reno, who had grown up BMX racing, tried numerous times to get connected to OORC, but never heard back. So, he did what most mountain bikers at that time did: He took a handsaw in his pack and cleared trail as he rode.

Aside from Devil’s Den, there were only two other places to ride before Slaughter Pen opened: Mount Kessler in Fayetteville (which was privately owned before the city purchased it) and the Upper Buffalo Headwaters in the Ozark National Forest, an hour southeast of Kessler near the community of Red Star. Both trail systems were nothing like the purpose-built trails that were to come. A nine-mile series of narrow, hand-cut, technical trails traced fall lines down Mount Kessler. Though they were steep and rocky, they were beloved by Fayetteville’s core riders and the original members of OORC who built them.

The Upper Buffalo trails were also old-school in flavor. Sometimes they were fast and smooth, sometimes choked with rocks. Unlike the singletrack at Mount Kessler, Upper Buffalo’s trails were essentially backcountry. There was no city center nearby, no people to call upon should you need assistance. That is, unless you knew How Kuff, a homesteader in the Upper Buffalo who cut in some 30 miles of trails there over a span of 20 years.

It was pure coincidence that Kuff stumbled upon the Upper Buffalo. In 1978, he and his then-partner had ended up in Fayetteville after months of hitchhiking around the country. Three years after first laying eyes on the Upper Buffalo, he purchased one of the few private inholdings there and built a homestead. In 1990, Kuff and the Newton County Wildlife Association went to battle against the Forest Service over the future of the Upper Buffalo. The Forest Service wanted to log it; Kuff wanted to protect it. Downstream of his homestead was the Upper Buffalo Wilderness and the Buffalo National River, which had been designated America’s first national river in 1972. Logging the headwaters of the Buffalo, he argued, jeopardized those federal protections downstream. The lawsuits landed Kuff and the Upper Buffalo’s supporters in federal courts, but eventually they won. In its 2005 revised forest plan, the Forest Service designated the Upper Buffalo Headwaters as a non-motorized dispersed recreation area.

By that point, Kuff and his neighbors had already begun to craft a mountain bike trail network. Though the trails had clandestine beginnings, the Forest Service wasted no time in adopting them and even bought Kuff a GPS device to map the trails. In 2002, Kuff and his neighbors started the Headwaters Challenge, an annual community bike ride that demystified the remote trail system and eventually became OORC’s largest fundraiser. Kuff says this partnership with the bike club helped to legitimize the Upper Buffalo’s trails. At the suggestion of OORC, Kuff wrote one of the first trail-related grant proposals to the Walton Family Foundation. In 2012, the Waltons awarded the OORC $300,000, mostly to build parking areas, install trail signs, and create trail connectors. Two years later, the Upper Buffalo Headwaters opened about 38 miles of backcountry singletrack to the public. That same year, IMBA designated the Upper Buffalo Headwaters as an IMBA Epic.

“THE MATH WORKS PRETTY DAMN GOOD. BUT IT WOULD NOT HAVE WORKED IF IT WAS JUST A CHECK FROM A FOUNDATION SAYING, ‘GO BUILD SOME TRAIL.’ IT HAD TO BE THE WHOLE COMMUNITY, ALL TOGETHER."—Gary Vernon

For many years, the Waltons funded trail maintenance in the Upper Buffalo, and for Kuff, that was huge. Before, it had just been Kuff and a few OORC members with chainsaws volunteering to clear trails on a nearly roadless 7,000-acre tract in the rugged Ozarks. But a few years ago, the Upper Buffalo lost that funding, and Kuff doesn’t know why. As the Waltons continue to pour millions of dollars into trail infrastructure close to Bentonville, creating more trails in Northwest Arkansas’ city centers than ever before, Kuff worries that mountain bikers today may never know the Ozarks he loves: a forest full of black bears, mountain lions, and post oaks so big around you can hardly wrap your arms around them.

“Nothing like that is in Bentonville,” Kuff says. “I’m not fond of billionaires. They always seem to do things in a way that benefits them.”

Gary Vernon doesn’t see it that way. The 54-year-old has worked for the Waltons in some capacity since the late ‘80s. His job at Walmart brought him to NWA in 2003. For 30 years, he climbed the corporate ladder there, eventually earning the Walton brothers’ trust. He was a mountain biker, after all, and served as president of the local NWA IMBA chapter, Friends of Arkansas Singletrack (FAST), for seven years.

In 2015, Vernon left his career at Walmart to serve as Program Officer for the Walton Family Foundation, where he oversaw all trail- and cycling-related initiatives until 2023. He was instrumental in rebranding the region’s trail systems under the Oz Trails umbrella, and helped the state parks execute the purpose-built Monument Trails network. There is hardly a mile of trail in NWA’s nearly 600-mile network that Vernon has not had a hand in bringing to fruition. Now, Vernon is the Director of Investments, Outdoor Recreation and Trail Innovation at the Runway Group, a holding company founded by the Walton brothers.

Although Vernon grew up racing BMX and has a deep appreciation for the old-school riding that Kuff treasures in the Upper Buffalo Headwaters, he says that remoteness is intimidating for a lot of riders. Even now, there’s no cell service in most of the Upper Buffalo, and the nearest hospital is more than an hour away in Harrison. As the demographics of mountain bikers changed over the years, Vernon knew NWA’s trails needed to adapt, too.

Most of NWA’s 600 miles of trails, which have largely been built in the past six years, were designed with accessibility in mind. From the huge hits at Coler Mountain Bike Preserve in Bentonville to the intricate rock lines at Passion Play in Eureka Springs, Vernon says every new trail network strives to include something for everyone, from adaptive riders to kids, professional mountain bikers, and everyone in between. That diversity is good not only for growing the sport, but also for creating a healthy community and a vibrant economy.

In the past few years, dozens of cycling brands and manufacturers have opened stores in or relocated to NWA, including Rapha, Strider Bikes, Specialized Bicycle Components, Allied Cycle Works, YT Bicycles, and Vittoria Tires. The Oz Trails’ popularity not only attracted new brands and business, but they also elevated the reputations of the trailbuilders who built them; companies like Progressive Trail Designs, Rogue Trails, Jagged Axe Trail Designs, and Rock Solid Trail Contracting.

Northwest Arkansas’ trailbuilding industry is expected to continue to grow. In 2023, the NorthWest Arkansas Community College Foundation received an $8 million grant from the Walton Family Charitable Support Foundation to establish a trails technician program and build a state-of-the-art lab at the school. Students will be able to gain certification in sustainable trails, trail construction and maintenance, and trails and community development while stacking these courses alongside a bicycle technician certificate, or into an associate degree in construction technology or general technology.

Last year, the University of Arkansas’ Center for Business and Economic Research released a study that found the cycling industry generated $159 million in total economic impacts in 2022 from cycling-related jobs, tourism revenue, and taxes in Benton and Washington counties. Vernon estimates that the Waltons have invested anywhere between $12 and $20 million building trails in those two counties.

“The math works pretty damn good,” he says, “but it would not have worked if it was just a check from a foundation saying, ‘go build some trail.’ It had to be the whole community, all together. Twenty years ago, kids were running out of town as soon as they got out of high school. Now people are moving here without a job. It’s all about having the trails. People want to belong.”

The combination of trail access, economic opportunity, relatively affordable cost of living, and the desire to belong are some of the driving factors behind NWA’s explosive population growth. According to U.S. Census Bureau estimates, NWA is one of the fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the country and is currently the 100th largest.

Justice Berry is one of the many mountain bikers who have relocated to the area in the past five years. Berry moved from Kansas City to Bentonville in 2022 for the mild year-round temperatures and the incredible variety of riding, but also because it was the one place he could actually envision raising a family. Kids growing up in NWA have the chance to ride trails to school, race on a team, even go to school to become a bike mechanic or a trailbuilder.

Berry loves that he can ride nearly every day of the year, even when it rains. On some trails, he says, you can ride 15 minutes after a thunderstorm and never get muddy. Berry leads a weekly e-mountain bike group ride on Mondays. The interconnectedness of the trails to the community, he says, is truly special. But life here can also feel a bit like living in a snow globe.

“Bentonville has such an influx of culture because of Walmart, Tyson Foods, and JB Hunt Transport,” Berry says, “but you couldn’t come down to Bentonville and say this is 100 percent Arkansas. Bentonville is an absolute melting pot.”

Sofia Reyes says the region wasn’t always so diverse. In 1990, when Reyes was 20 years old, she moved from Mexico to Bentonville with her cousin, Olivia Barraza, to work for Walmart. Back then, Reyes didn’t have much time for recreating. A single mother of two, she was busy keeping food on the table. Eventually her kids grew up and moved out. Reyes was 45 and, too soon it seemed, an empty nester. She thought, what now? Her cousin had started riding mountain bikes and Reyes, ever curious, decided to give it a try.

“I live here. How could I not be part of it?” she says. “When [Olivia] invited me to her biking group, I looked at them and I felt like we were back in 1990. I didn’t have the body type, I didn’t look like them, I didn’t have a nice bike. I felt awkward. I wanted to ride, but I didn’t feel like I belonged.”

She and Barraza wondered, where was their community? When the two cousins first moved to NWA in 1990, the region was only 1.3% Hispanic and Latino, according to data from the Northwest Arkansas Council. But as of 2021, that population had grown to 17.3%. Those faces were not reflected in the bike community, so Reyes and Barraza decided to change that. In 2019, they founded Latinas en Bici, a cycling nonprofit that specifically serves Latina women. Their mission is to break down cycling’s barriers to entry, be they financial or cultural, and to create a safe place to build community.

In the four years since its inception, Latinas en Bici membership has increased from 10 members to more than 120. They lead a number of weekly group outings, including mountain bike rides which they offer every other Tuesday. Their Bici Escuela teaches the basics of cycling exclusively in Spanish. Every session has a waitlist. Reyes says Bentonville’s well-maintained systems, abundance of beginner-friendly trails, and proximity to neighborhoods have been critical to Latinas en Bici’s success.

“I just turned 54 and I can’t believe I’m mountain biking at this age,” she says. “I love to see our older women mountain biking. I call them chingonas. They’re awesome.”

For Rachel Olzer, the Executive Director of All Bikes Welcome, this is the power of NWA’s trails. That women of color can access a mountain bike community that looks like them, that shares their lived experiences, is deeply impactful. Olzer moved to Bentonville from Minneapolis at the end of 2021 and started at the nonprofit in 2022. All Bikes Welcome’s mission is to increase racial and gender diversity in cycling. Their bedrock event is the Grit MTB Festival, a three-day mountain bike gathering created by and for marginalized folks in the cycling industry.

Some days, trying to further diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts in NWA feels like a tall order. Olzer says it’s the hardest job she’s ever had, but she’s hopeful.

“In my limited understanding of living here, this is probably an unprecedented amount of change for a southern state, and with that there’s an opportunity to really examine the values and traditions that have kinda ruled this area of the country,” Olzer says. “I think this place is really magical in that it shows when you put resources towards something, when we prioritize very specific things, we can move literal mountains.”

Bea Apple shares that pragmatic optimism. In 2020, Apple and her friend, Kim Seay, founded Bike.POC, an organization that initially started as a solidarity ride for the Black Lives Matter movement. It has since grown into an advocacy group aimed at creating a safe and inclusive environment for BIPOC and LGBTQ+ folks who ride. Apple is still an entrepreneur—in 2018, she and her business partner opened a textile studio and shop called Hillfolk— but she’s also an advocate for equity-based cycling and transportation infrastructure in and around Bentonville.

She says NWA is uniquely positioned to rewrite the collective understanding of what bikes can do for rural America. Only time will tell if the region can rise to the occasion, but Apple hopes that the resources and energy behind trails are indicative of a bright future.

“This is a testing ground. We need to breathe new life into rural communities and communities of color that have long been left out of the conversation,” she says. “I 100 percent believe that this place and these people can continue to push the needle towards a good direction. Where we are right now is the product of someone’s imagination, and this place is really poised to be imaginative.”