Pedal to the People A New Wave of Americans Discover Mountain Biking

Words by Ian Terry

If 20th-century American recreation conjures visions of baseball fields, soccer balls and playgrounds, then the 21st may well be defined by the rise of trails, kneepads and pumptracks.

Once content with shoveling tax dollars toward expensive community swimming pools or tennis courts, record numbers of everyday people are turning to the modern mountain bike as a viable tool for reshaping the economy of towns emerging from an era of outdated industrial practices, or as a gateway to healthier living.

This movement has been simmering since the mid-2000s, a period in which small bands of dedicated riders began to finally make meaningful inroads with local land managers after a spate of bike bans took hold across the United States and largely confined mountain bikers to select plots of subpar trail. Today, stories of bike towns abound—Bellingham, Washington; Bentonville, Arkansas; Moab, Utah; East Burke, Vermont; Brevard, North Carolina. But these hallmark hotspots, which garner ample attention in mainstream mountain bike media as well as general news outlets, are just the tip of the proverbial trail spear. Aided in part by throngs of Americans flocking to the outdoors to safely recreate during an unrelenting pandemic, demand for new trails and use of existing ones have never been more pronounced. The International Mountain Bicycling Association (IMBA) reports land managers have tracked anywhere from 100-to 500-percent increases in trail use during the past two years. This groundswell is leading to crowding at established trailheads, swarms of mountain bikers at new ones and calls for more infrastructure in areas where riders must drive long distances to get their fix.

The rush to trails is fostering entirely new demographics of Americans to steer their bikes off pavement and onto dirt—often for the first time since childhood—on terrain never intended for sustainable recreation. In Burnet, Texas, a hill described by one local as mostly a place “people went up to and partied” is now Spider Mountain Bike Park, the U.S.’s only year-round, lift-serviced bike park. In Anniston, Alabama, nearby Fort McClellan, a former U.S. Army post, was converted into a trail system designed specifically to host student league mountain bike races. In Chisholm, Minnesota, abandoned iron ore mining pits are now home to a robust 25-mile network of multi-use singletrack geared toward bikes. In Brunswick, Maryland, a father and son duo convinced local officials to turn a 59-acre tract of city property, a section of which used to be a landfill, into a four-mile multi-use trail system as part of the town’s effort to rebrand itself from a coal and railway hub to a friendly outdoor-minded community of some 7,000 people on the brushy banks of the Potomac River.

It took local Tara Ward two tries before she found the new River’s Edge trails. Operating on rumors from friends, Ward discovered the system and began walking them with her two kids, dogs in tow. The woods at the eastern edge of Brunswick are dense, though treasures abound for those who venture into its dark thickets. Groves of native pawpaw trees and patches of prized mushrooms are sought after by some in the area. Until Ward came upon fresh jumps and berms while meandering through the forest, she says the totality of her knowledge and prior experience with mountain biking consisted of being “vaguely aware that it existed.” Soon, she was wading through gobs of information to learn more and venturing out on her hybrid bike.

“It was intense, and it was scary,” Ward said. “But there were these times when I was just kind of flowing on the cross-country trails and thought, ‘Wow, I like this.’”

Ward’s next obstacle as a new mountain biker, as thousands of fellow Americans who also took up the sport in 2021 came to find, was navigating supply chain issues and low stock. Unprecedented disruptions and shipping delays, caused by COVID-19 and exacerbated by the U.S.’s heavy reliance on Asian bike frame and component manufacturing, merged with a level of demand not seen since the early 1970s to create a perfect storm of bicycle scarcity at a moment when interest was riding high. So, after parsing through options at her local bike shop, Ward upgraded from her trusty hybrid and settled on a Liv hardtail. She’s working up to confidently riding the berms at River’s Edge. Her 11-year-old son, Will, can’t get enough of them. Before receiving his own bike for his birthday, he preferred his mom’s even though his feet couldn’t touch the ground. Undeterred, Will simply got used to falling.

Earlier this spring, Will joined Carlo Alfano, who first presented the idea of the River’s Edge system to the City of Brunswick, and other volunteers to help tune up the trails after a long winter. In a year Will is eligible to begin riding with his local National Interscholastic Cycling Association team, which, thanks to the work of the Alfano family, now has a home trail system for youth interested in cycling. And even though he’s not yet old enough to formally join, Will is already attending meetings.

“It’s his passion,” Ward says of her son’s interest in mountain biking, “He’s a kid who just seems to have this urge to physically test the environment around him in any way that he can.”

If Will had grown up in Brunswick just a decade or two ago, he would have spent his childhood testing the environment in other ways than flying down professionally sculpted jumps on a bicycle. Like millions of other kids, he might have joined the local little league instead. Of course, he may still decide one day that he prefers baseball over mountain biking—or chess, or playing violin for that matter. But River’s Edge gave him a taste for dirt that can’t be taken away. As more and more riders like Will and his mom discover riding, once-tepid partnerships between mountain bikers, parks departments and land managers are evolving in some progressive regions into an all-hands-on-deck push to make space for the next phase of American mountain biking.

IMBA, once goaded by some for having most of its staff based in Boulder, Colorado, is spreading its trailbuilding tentacles across the U.S. to position itself for a focused effort to bring new mountain bike infrastructure to 250 towns and communities by 2025.

“We’ve got a couple people in the front range of Colorado,” says Dave Wiens, who works as IMBA’s executive director and lives in Gunnison. “Kent [IMBA’s CEO] is in Omaha. We got folks in Maine; Massachusetts; North Carolina; Prescott, Arizona; the Bay Area; Arkansas; Madison, Wisconsin. Everyone is involved in their local advocacy and brings different perspectives to the conversation.”

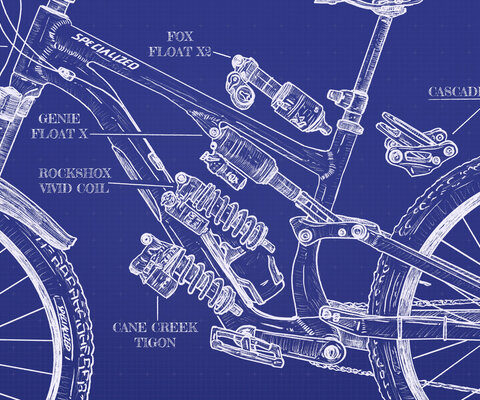

Diversifying where staff lived meant Wiens, alongside CEO Kent McNeill and other leaders in the organization, were already used to hopping on Zoom calls or picking up the phone to chat with colleagues before the pandemic hit. A spread-out team allows each member to learn dos and don’ts of trail advocacy in their area and then report back to share information where needed. McNeill, who joined IMBA’s staff in 2018 after serving on its board since 2013, likes to think of building trails and advocating for increased mountain biking opportunities as an endeavor with region-specific nuances—not dissimilar to how riders in various locales may have different equipment preferences that essentially do the same job.

“What we’re learning is that there is kind of a process that everybody goes through,” McNeill says, “It’s like building a bike, you have so many choices of what drivetrain, what tires, what frame type—it’s all different for the individual communities. There are all these local flavor-type decisions you get to make, but then there’s just things you can’t avoid that have to be part of the process or you don’t end up with what you want in the end.”

As McNeill prepared to make the jump from IMBA board member to full-time staffer in the late 2010s, feedback from partners, community members and everyday riders was increasingly based around creating more accessible options than the typical blues and blacks commonly built by veteran mountain bikers. But while adding more beginner runs to existing systems might make for a more enjoyable experience to newcomers fortunate enough to already live in areas close to trails, it wouldn’t do much to introduce the sport to people like Tara Ward—people who, until a trail opens within easy access of where they live, would likely never throw a leg over a knobby-tire bike with suspension and pedal off down a narrow dirt path.

“What would it look like if we really put an emphasis on bringing trails close to home?” McNeill said, repeating a question that IMBA’s aptly-named More Trails Close to Home campaign hopes to chip away at answering during the coming years. “For most people, if their only option is to load up a bike and drive an hour away, it’s just not an activity they’re going to be able to do often.”

IMBA’s brand of trail egalitarianism crystallized at the start of the pandemic, when even intrastate travel was restricted in many regions in an effort by local health officials to prevent a spread of infections. COVID-19 cases have since ebbed and flowed. The cost of travel is only rising. Recent Consumer Price Index reports show the highest increases in consumer costs during the past year are attributed to oil and gas prices. Put in mountain biker terms, the more you rely on diesel, gasoline or jet fuel to access trails, the harder inflation is hitting your wallet. This increasing cost far outweighs inflation associated with food products (ride snacks), medical care (broken bones) or hard goods such as apparel (new gloves). As Americans feel the squeeze, an opportunity to safely ride a bicycle close to home looks less like a neighborhood perk, and more like an elemental antidote for uncertain times.

“If we want mountain biking to be as commonplace—no matter where we live—as ball sports and ball fields, we have a lot of work to do,” McNeill said.

Fortunately for IMBA, work is humming. The nonprofit netted $1.5 million in revenue in 2021, a million-dollar increase over the year prior. On the ground, project planning and new trail construction are moving forward. On May 6, 2022, the community of Erwin, Tennessee, hemmed in by the Blue Ridge Mountains, gathered under cloudy skies to formally open the first phase of the new Unaka Bike Park, a two-mile network of flowy green and blue runs that lies within earshot of the town’s middle and high schools. Unaka was partially funded by an IMBA Trail Accelerator grant, a program that helps bike advocacy groups get the cash they need to kickstart projects that already have local buy-in. Fundraising for the second phase of the trail system is now underway. When secured, six more miles of singletrack ranging in difficulty from beginner to expert will be added to this land owned by Erwin Utilities—once used only as a protected watershed before adding outdoor recreation amenities.

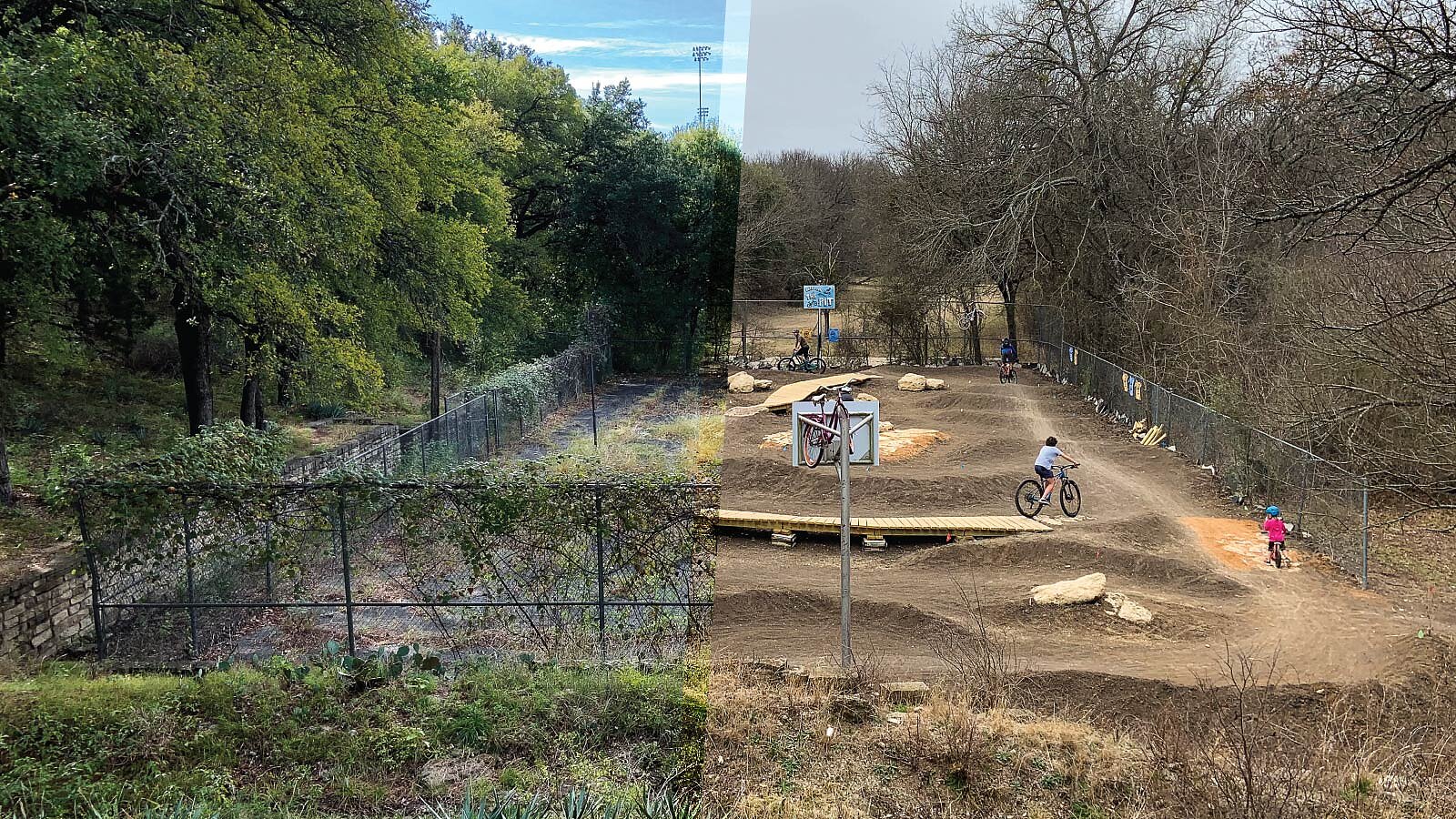

Not all IMBA’s successes are measured in miles, however. Some notable projects have taken shape on pieces of land barely a few car-lengths wide. A former overgrown and dilapidated tennis and basketball court known as “the Pit” to Weatherford, Texas locals is now a small bike park filled with features to get kids and beginners hooked on riding, thanks to a collaborative effort between IMBA, the Weatherford Mountain Bike Club, local city officials and Shadow Trail Designs, a private trailbuilding contractor.

“It used to look like something out of the Walking Dead,” Wiens said, referencing the Pit. “Next thing you see is it’s a cool little skills area full of people on bikes.”

Around two years ago, IMBA started tracking progress toward its More Trails Close to Home mission. The latest figures: 44 created, 58 committed, 353 engaged.

As seeds are sown for the future of mountain bike infrastructure across the U.S., towns with newly established, thriving trail systems offer clues for healthy growth. And as success stories emerge, a sometimes-elusive mixture of land access, local on-the-ground enthusiasm and unlikely partnerships appear to be driving many of America’s burgeoning bike towns.

Josh Blum’s podcast, “Trail EAffect,” is focused entirely on digging into the nitty-gritty of American mountain bike trail development. Blum, who lives just outside La Crosse, used to spend hours on the road at his former position with the Wisconsin Department of Transportation. To fill his time behind the wheel, he’d put a podcast on when the constant stream of NPR or other available stations grew monotonous. Blum is no stranger to bicycle advocacy either. He’s dedicated countless hours of volunteer time maintaining his local trails, some of which he helped bring to fruition via IMBA grants. Combining his interests, he set out to record and document cases of modern mountain bike growth, as well as challenges.

“Through all of this, I kept having questions about how other communities are doing this,” Blum says. “I know you can’t replicate the same model everywhere, but if you could take bits and pieces from all these different places, maybe you could create a roadmap of what works and what doesn’t—and maybe you could also start spotting trends.”

In the 80 episodes he’s published since starting the podcast in late 2020, Blum has noticed bellwethers of mountain bike prosperity-to-be. For one, communities that position trailheads within a reasonable riding distance of where residents live stand the best chance of organically cultivating outdoor culture because having to drive, even short distances, can deter people from getting out to ride. Another lesson learned—one Blum stresses to anyone who asks him how to get trails built in their town—is that planning must be done up front.

“Sometimes in the plan you have things identified, environmentally or otherwise, that you need to address,” Blum said, “But it’s also a good way to show the community that may not be involved in mountain biking, or may not even know what mountain biking is, that you are actually trying to do something legit.”

Planning for trails, in the case of Chisholm, meant first disentangling restrictions for public use of abandoned mining sites. In this northeastern Minnesota town, iron ore is a source of pride. Metals extracted from vast, man-made pits here were used to build tanks and planes during World War II, then glistening skyscrapers in major metropolitan areas such as Chicago and New York City in the years that followed. Today, mining accounts for a much smaller segment of Minnesota’s economy. But it remains inextricably linked to local culture—something advocates for the Redhead Mountain Bike Park set out to honor when they first began the hard work of gaining access to a 1,225-acre site just south of Chisholm.

In 2018, a decade of perseverance paid off for Minnesota outdoor recreation dreamers when a bill was passed that eased existing laws around fencing people out of former mine sites and provided certain exemptions for parties interested in developing the land further for public trail use. The legislation, authored by former state representative and current Deputy Commissioner of the Iron Range Resources and Rehabilitation Board, Jason Metsa, marked a vital jumping off point for community advocates to begin truly shaping Chisholm into a hub for trails.

“Without that cooperation between multiple agencies and landowners and community advocates, Redhead would just be a dream,” says Jordan Metsa, who works as the development director at the Minnesota Discovery Center in Chisholm and also happens to be Jason’s brother. “It’s breathing new life into an area that has kind of sat stagnant.”

Since the Redhead trail system first opened in 2020, the Minnesota Discovery Center has added a full-service bike shop, including rentals, to its longstanding repertoire as a purveyor of local history, stories and knowledge. From the trailhead at the center, riders fan out onto 25 miles of multi-use singletrack set against canyons, gulleys and cliff edges that emerge from ghostly, blue water. During summer months, Kermit-green leaves provide a stark contrast to burnt-orange rocks and dirt. Expert riders have trail options like Fractured Falls and Deep Water while beginners can cruise Spell Bound or make their way out onto the North Star Loop. Hikers and trail runners are welcome on all Redhead trails and, to expand access even further, kayak and canoe rentals are offered too.

Candice Sjogren opened 30West Fitness and Recreation in early 2019. Her husband, Joel, is a Chisholm native who works at a local mine. The Sjogrens, together with business partners Jen and Nick Gigliotti, were only just beginning to see their new fitness facility come into its own when statewide COVID-19 mandates required gyms to shutter. The plan for 30West had always been to expand beyond the gym, so with the pandemic hampering business, they decided to present an idea to the Minnesota Discovery Center: Open a bike shop and rental service to help provide equipment for anyone interested in experiencing Chisholm’s mountain biking.

The plan had its hiccups. Fleets of rental bikes weren’t easy to come by during the pandemic, but instead of scrapping the idea entirely, they used the extra time to hone their knowledge of mountain biking which, between 30West’s four owners, was limited to Joel having ridden a bit during college in Duluth. When classes were still being offered, Joel flew to Colorado to take an intensive mechanic certification course at the Barnett Bicycle Institute. The instruction gave him the foundation of knowledge to begin offering basic tune-ups. 30West’s bike shop is now running full swing, with younger high-school age employees learning how to set up suspension on rental bikes or assist customers with minor repairs.

“Sit down, look at a screen—there’s so much of that in our lives now,” says Sjogren, who frequents the trails with her 3-and 5-year-old kids, Noah and Stella. “Here’s this opportunity to go have fun, to be active, to start this culture of movement that kids can carry on for their whole lives.”

The Chisholm mountain bike community is eagerly awaiting summer. Many in town, including Metsa and Sjogren, believe this season will be the first true test of the new Redhead system. Will visiting riders enjoy the terrain enough to tell their friends? Will locals embrace a sport that, until last year, many had never heard of?

For now, Chisholm, like so many other developing bike towns, is playing a game of wait and see. A sense of communal confidence is rising in tandem with the shift to warmer weather. Build it. Trust they’ll come.

Learn More About Biketown