Electric Slide How eMTB Growth Is Transforming the Mountain Biking Landscape

Words by Ian Terry

In a conference room at Angel of the Winds Arena in Everett, Washington, Yvonne Kraus pulled out a pair of red boxing gloves, raising them as she stood on stage before a group of outdoor recreation stakeholders gathered to hear her speak in October of 2022 on the topic of mountain bikes with electric motors.

“Were any of you there in 2018 when I brought these out?” said Kraus, who works as the executive director of the Evergreen Mountain Bike Alliance (EMBA), a statewide nonprofit trailbuilding and advocacy organization. Six or seven people quietly raised a hand.

Kraus was referring to a previous Washington State Trails Coalition conference, one of the first times she broached the touchy topic of electric mountain bikes, or eMTBs, to a packed room of hikers, equestrians, hunters, conservationists, land managers, and fellow riders hungry to learn more about how one of the state’s trail development leaders was navigating her way through the most significant technological leap of the sport’s history—a leap that has revived worry from old-guard, not-in-my-forest Sierra Club-types, as well as old-school mountain bikers bent on preserving the “no pain, no gain” ethos.

The gloves came off. Kraus smiled. She wasn’t looking for a fight, but, rather, for a breath of levity before diving into a subject that has positioned her at various points since she took the helm of EMBA in late 2015. Over the past several years, and depending on the situation, she has been a sensible advocate for, a sober policy advisor against, and a knowledgeable educator about eMTBs.

“This project has taken way too much of my time over the past few years,” Kraus said as she flipped through her first few slides.

Her work making sense of eMTB-adjacent recreation policy minutiae and legalese comes at the end of a period of intense development within the overall bicycle industry. While pedal-assist electric bicycles aren’t new (AeroVironment, of Paul B. MacCready fame, and GT Bicycles collaborated in the ‘90s to make the lead-acid juiced “Charger”), rapid lithium-ion development allowed performance mountain bike manufacturers to begin designing around the technology in earnest by the mid-aughts.

During this same period, and on through the 2010s, huge gains were made in the frame geometry, suspension design, overall weight, and durability of traditional mountain bikes. Their eMTB counterparts were much heavier and typically lagged a year or two behind whichever headtube angle, reach or chainstay length was in vogue, but that has begun to change. Apart from the inclusion of an inconspicuous motor, eMTBs and MTBs are now more alike than ever before. This amalgam is redefining the culture of mountain biking, and, in the eyes of some, reconstituting what it means to be a mountain biker.

Apart from the inclusion of an inconspicuous motor, eMTBs and MTBs are now more alike than ever before.

A veteran rider, in an example of the latest tech available, could hop on Trek’s newly released Fuel EXe, a lightweight, sleek, mid-travel eMTB the company dubbed as “a new breed of mountain bike,” and feel completely at home given that it weighs just a few pounds more than many burly enduro rigs. A beginner could feel like a superhero, as the bike’s nearly silent, modestly powered, harmonic pin ring transmission provides a subtle boost to their churning legs. Hikers or fellow riders they stop to chat with would be hard-pressed to recognize the bike as housing a motor, given that it looks virtually identical to other traditional mountain bikes produced by Trek, barring a slightly more pronounced bottom-bracket area and a tiny digital display integrated into its top tube.

What has not developed in lockstep with eMTB technology is policy surrounding their use on trails. For countries in the European Union, legislation provides a baseline regulatory standard that allows electric, pedal-assist bikes—as opposed to those with a throttle—to be classified as bicycles, with no need for special licensing, so long as they don’t produce more than 250 watts of continuous power, and don’t continue to propel riders after reaching a speed of 25 kilometers per hour (about 15 mph). The result is broad acceptance on most singletrack for low-powered eMTBs.

When she publicly presents about eMTBs, Kraus, who is Dutch, often shares a story of stopping at an Alpine hut and noticing that she and her riding partner were the only riders sporting traditional mountain bikes. A picture she snapped that day tells the story; bluebird skies, stunning views, smiling faces, eMTBs leaned against railings, helmets and clothes draped across handlebars to dry in the sun as those gathered enjoyed a beer or coffee before descending to lower elevations.

Such a harmonious scene doesn’t exist in North America, especially not in the United States, where rules about eMTB access on singletrack are complicated and often differ from state to state or even trail to trail within the same area in accordance with wildly varying rules set by local land managers.

In North Bend, Washington, where EMBA is headquartered, any visiting mountain biker would drool at the sheer number of trails to explore within 30 minutes of town. But on an eMTB, those options are difficult to sift through for even the most diligent riders. Duthie Hill Park, a renowned bike park on 120 acres, is off-limits per King County’s rules. The trails at Raging River or Tiger Mountain, which lie on land managed by Washington’s Department of Natural Resources, are fine—but only with an ADA placard. How a rider would display this on trail is not exactly clear. Tokul, a popular winter trail zone on private logging land, is a no-go; private landowners, of course, can set whatever rules they want. Kachess Ridge, a summertime backcountry classic, is governed by the U.S. Forest Service, which announced in a policy clarification in early 2022 that all eMTBs would continue to be classified as motorized, and thus disallowed from nonmotorized trails while leaving the option for future consideration of opening some individual trails to motorized users “in accordance with the Travel Management Rule (36 CFR Part 212, Subpart B).” Across the valley, Olallie State Park is fair game, as that’s Washington State Parks’ domain, and they recently decided to allow Class 1 and Class 3 eMTBs. What’s the difference between Class 1 and Class 3? Eight miles per hour, to be exact. Got it?

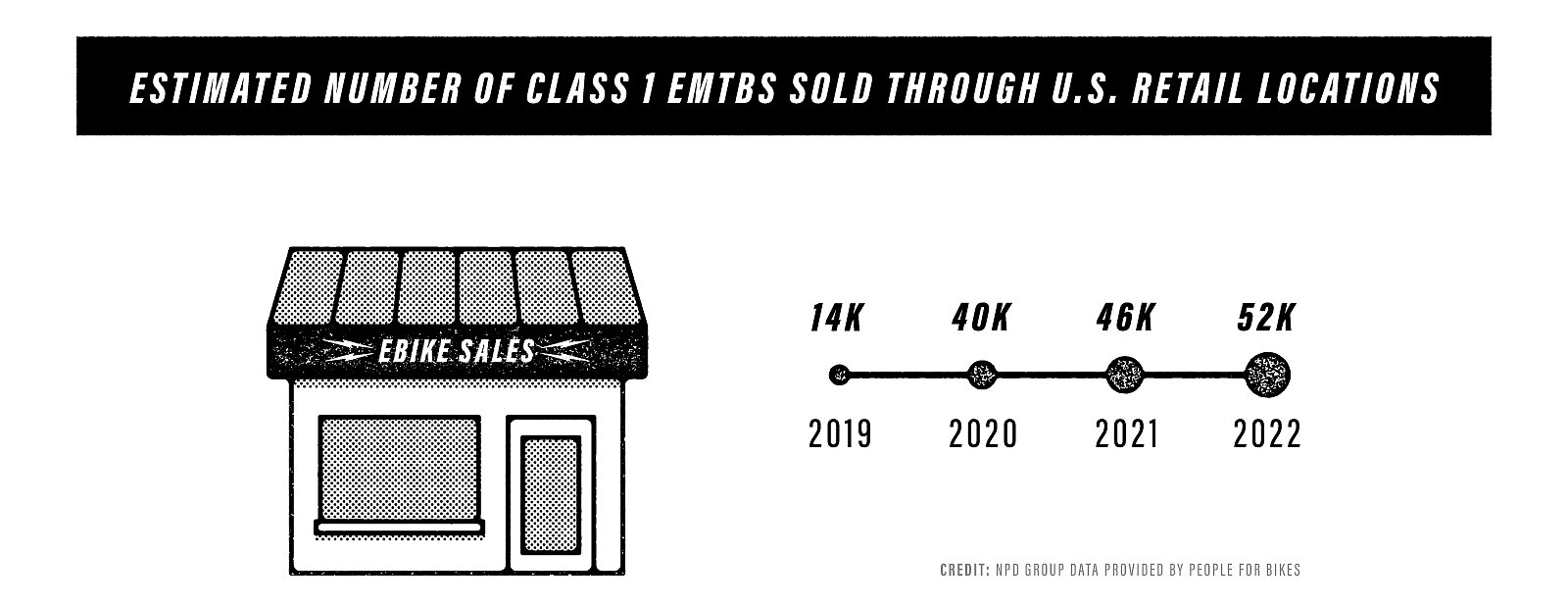

“E-bike growth was 140 percent in the mountain bike industry in 2020 [for some companies],” Kraus said. “A whole lot of market growth turns into customer confusion— ‘Where are these bikes allowed? Where do we go?’ There’s increased pressure on legislatures to take action.”

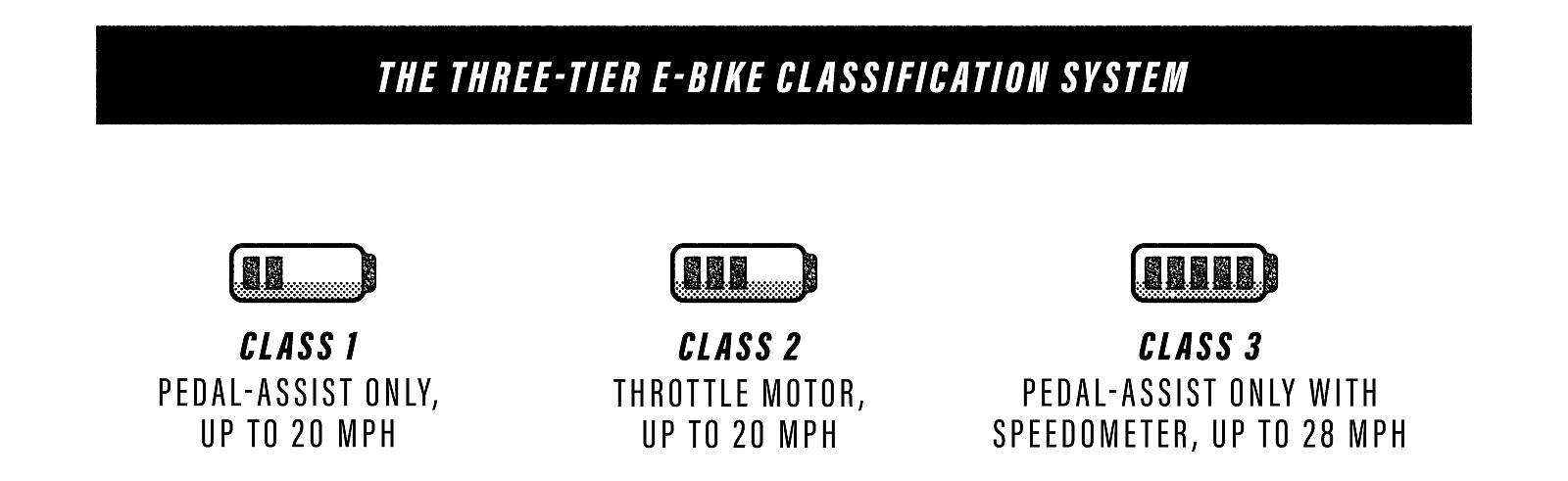

Legislation passed in Washington in 2018, which EMBA supported, provided a framework for future regulation on trails in the state by establishing the class 1, 2, 3 system, a method of categorizing e-bikes based on whether they are equipped with pedal-assist (classes 1 and 3) or throttle technology (class 2), and by their maximum motor-powered speed. It also capped continuous power at 750 watts, or roughly one horsepower, a notable bump in strength over eMTBs in Europe, which output power more akin to one mild-mannered donkey at 250 watts. Wattage output by humans varies, of course, by fitness, but isn’t far off from a common, lower-powered eMTB. Elite cross-country racers regularly lay down efforts exceeding 350 average watts during 90-minute efforts, with spikes of more than 1,000 watts. A moderately fit cyclist can average around 150 watts for the same length of time. Thus, European eMTBs allow average mountain bikers to ride like very fit people, while American eMTBs allow average mountain bikers to ride like Gore-Tex Gods, at least if there aren’t any pesky roots or other obstacles in their path.

European eMTBs allow average mountain bikers to ride like very fit people, while American eMTBs allow average mountain bikers to ride like Gore-Tex Gods, at least if there aren’t any pesky roots or other obstacles in their path.

The laws, in crucial points, also separate and call out differences between e-bikes of the urban commuter variety and mountain bikes, classify e-bikes as bicycles, and give land managers authority to grant them access to singletrack trails. To date, 39 states use the three-tier system, with California being the first to set this precedent in 2015 as People for Bikes, a bicycle industry advocacy group, began its push for more homogenous e-bike laws across the country.

The mountain bike industry has thrown its weight behind the class 1 category: pedal-assist only, with a motor that cuts out when speed exceeds 20 mph. This approach has alienated some off-road e-bike users, most notably hunters, who often advocate for trail access for high-powered, throttle-equipped models that can be purchased at outdoor stores such as Cabela’s and allow for fast access into remote areas. A lack of regulation in the U.S. allows manufacturers within this niche market to blur classification lines. An advertisement for one such bike, available on a prominent hunting outfitter’s website, notes that its “powerful Bafang Ultra-Drive motor delivers up to 1,500W [watt] peak to get you up just about anything. This Class 2 E-bike has both pedal-assist and a removable thumb throttle that can be unplugged to meet Class 1 regulations.”

A Washington Department of Natural Resources and Department of Fish and Wildlife (DNR and WDFW) report, released in September 2022, digs into findings from an extensive public and local stakeholder engagement process intended to research eMTB and e-bike use on land they manage. The report was required by the Washington legislature and was intended to inform future decisions about where eMTBs may or may not be granted access. Perhaps unsurprisingly, one of the main conclusions was that, as the agencies wrote, “There is no workable one-size-fits-all approach for managing e-bike use on a statewide level for either DNR or WDFW.”

One main reason for this determination is that every area managed by DNR and WDFW is completely unique. Regional ecology, especially in a state such as Washington, varies enormously. West of the Cascade Mountains, soil types tend to be dark, loamy, and, for much of the year, filled with moisture. Further east, the earth gets drier and sandier. Within each biome, subtleties and exceptions only flourish further across small distances, sometimes by a few degrees registered on a clinometer, or by how much light a mountainside receives based on its orientation to the sun. Every case could, with more study and data collection, show differing levels of ability to withstand increased traffic from riders now able to ride farther on eMTBs.

But, for now, that’s all hypothetical, as only one significant study exists that tackled the issue of impact of this technology on natural surface trails. That study, completed in Oregon in 2015 by the International Mountain Bicycling Association under contract with the Bicycle Product Suppliers Association (the manufacturing segment’s arm of People for Bikes), found very small differences in soil displacement between traditional mountain bikes and class 1 eMTBs, while also cautioning that "No broad conclusions should be made from the observations presented."

Washington DNR has conducted some of its own on-the-ground e-bike research, too. A pilot project granted class 1 eMTB access to new, technical downhill mountain bike trails in Darrington, Washington, which it built in partnership with EMBA on North Mountain.

“The purpose of that [pilot project] wasn’t to capture broad public input,” said Sam Hensold, a recreation grants manager at DNR. Instead, he says, it was meant to provide insight into questions such as “What types of experiences do users have when you open up to e-bikes? What are their perceptions about e-bikes out there? Who comes? Are they shuttling or pedaling to the top?”

Of the 300 responses, 32 percent said they rode at North Mountain specifically because of e-bike access and 78 percent said they supported eMTBs on trails there. Hensold notes that this finding represents a much more positive lean in favor of the technology than the answers to a question DNR asked the public about broad eMTB access in its statewide report. Those responses were evenly split for and against: 41 percent indicated that e-bikes should not be allowed on DNR and WDFW nonmotorized natural surface trails, while 40 percent indicated that they should. The remaining 20 percent responded that a case-by-case basis would be appropriate. In total, 7,270 responses were recorded.

The DNR report also highlighted top concerns most often brought up by those who oppose nonmotorized trail access for eMTBs. In order of most-cited potential issues on the report: Trail safety and the speed at which e-bikes can go, potential impacts to trail conditions, and potential environmental impacts. Those most familiar with the nuances of riding class 1 eMTBs versus similarly spec’d traditional mountain bikes say differences in speed are negligible during fast descents, moderate (as in a few miles per hour) on flat terrain, and most pronounced on non-technical, easier-graded climbs.

In Washington, local Indigenous tribes have, in recent years, weighed in on broader environmental impacts of outdoor recreation, a segment of which encompasses increasing eMTB and MTB use. In January 2022, the Snoqualmie Tribe, whose ancestral home includes the North Bend area, released a report titled “Recreation Impacts on Snoqualmie Tribe Ancestral Lands,” that, in one section, outlines concern about strain on elk populations caused by increased hiking and mountain biking at Raging River and Tiger Mountain. The report cites a 2009 study from a different area of the state and calls for a more robust effort to collect pertinent data. It doesn’t mention potential impacts on wildlife from commercial activities that occur in the same area such as logging.

“We need to fully understand our impact before we can move forward together,” a website that houses the report reads. “Otherwise these lands that we love will not thrive, and neither will we.”

The DNR also collected input from local tribes in its statewide report. The coalition was comprised of 37 individuals hailing from 19 tribes, and all expressed concern about e-bike use, mostly in how the technology could theoretically lead to environmental decline, including harm to wildlife and vegetation, because of how the technology allows riders to travel farther into remote spaces. To mitigate this potential issue, Hensold foresees a future in which eMTBs are only granted access to DNR-managed recreation areas that don’t connect to deep backcountry and are instead reserved for self-contained trail networks.

Kraus believes much of the onus for successful integration of class 1 eMTBs on existing mountain bike trails falls squarely on the individual—that is, being respectful of other trail users, controlling speed appropriately, and only riding where it is legal.

“It’s not so much the technology, even though there’s concerns with that,” she said during her talk at the trail conference in Everett. “It’s very much how the user chooses to use that technology."

EMBA’s membership, which is currently approaching 10,000, is becoming more accepting toward eMTBs with each passing year. In 2019, the first year a question about eMTBs was included in its annual member survey, the results indicated 50 percent support of the nonprofit spending time and resources to introduce class 1 eMTBs, 34 percent preferring they did not, and 16 percent with no opinion. Their most recent surveys indicate a support level at around 60 percent. An eMTB-specific survey the organization conducted found 75 percent of those who participated fell somewhere between feeling neutral about allowing class 1 eMTBs on trails and strongly supporting their inclusion.

“We can argue about whether it’s right or wrong to have an electrically driven motor on a nonmotorized trail—that’s really the only way to look at it black and white,” Kraus said. “But when it comes right down to it, the implementation really hasn’t led to any more conflict. And that’s what we need to look at, whether we like it or not.”

Kraus, at EMBA’s annual member meeting held virtually on December 6, 2022, announced that the organization was adjusting its stance on e-bikes to encourage land managers to take an “open unless signed closed” approach to adopting class 1 eMTBs on trails already open to mountain bikes. The move is a reversal of its previous “closed unless signed open” recommendation and comes after years of collecting input from hikers, equestrians, mountain bikers, land managers, and other members of Washington’s outdoor recreation community.

Beyond the world of committees, stakeholders, conferences, Zoom calls, and other formalities, those who have already incorporated eMTBs into their regular riding routines are often hard to pigeonhole. Some want to ride farther in less time, and some just want to take the edge off of difficult climbs, but others are integrating the technology into their lives in ways that would have been hard to imagine a few years ago.

Davey Simon, a pilot with Alaska Airlines, is enjoying his new Pole Voima, which, he says, allows him to self-shuttle without a car at downhill areas during odd hours amid his sporadic work schedule. CJ Johnson, an engineer, found “a form of meditation” during the pandemic by tinkering with different motors in his garage to learn about the technology. He now hopes e-bike manufacturers will get serious about adopting a “right to repair” design mentality so consumers can more easily care for their own equipment. Kerstin Holster, a technical rep at Specialized, uses her eMTB to get out for fresh air and exercise when a connective tissue disorder she suffers from makes traditional cycling too painful. She had an epiphany on her first eMTB ride: “I remember riding up a hill and thinking, ‘Holy shit, this changes everything.’”

Sol Wertkin believes an e-bike saved his life.

“I was suicidal,” said Wertkin, a 44-year-old father of two who lives with his family in Leavenworth, Washington. “I have no idea how I would’ve got through that time without my e-bike.”

That troubling time began in the winter of 2020, when he noticed he was constantly feeling rundown and, mysteriously, losing weight. He shook it off at first. After all, Wertkin thought, most everyone he knew—especially his colleagues in nursing—was experiencing some level of burnout during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Gritting through pain and discomfort was familiar territory too. Most of his adult life has been dedicated to pushing his limits in the mountains. Wertkin pioneered a number of climbing routes in the North Cascades, including a particularly hairy first ascent of a new, 8-pitch route on Mount Stuart dubbed “King Kong.”

So, it came as a shock when a softball-sized tumor was discovered in his right lung. A month later, he underwent a 7-hour surgery, conducted by five surgeons, to remove the growth which left him with a fraction of his original lung capacity. The procedure also severed his phrenic nerve, causing his diaphragm to atrophy to the point of smashing his already compromised lungs. The ensuing months were hellish. Just walking to the bathroom left him keeled over, panting for air. Sleep was fitful, at best. When it did come, he’d awaken in a fog of carbon dioxide that his body hadn’t properly expelled. His mental health deteriorated.

Seeking a lifeline, Wertkin’s wife, Ginnie Jo, drove to Seattle and purchased two Rad Power e-bikes. Anything to get them outside together, she thought. Anything to bring him even a few moments of relief. It worked.

Wertkin was soon riding the fat-tire rig all over gravel roads in central Washington, sometimes with an extra battery stowed away in his pack. He quickly noticed that the position the bike put him in—seated, with his hands and arms supporting his torso—mimicked the “tripod position” that the human body reverts to for relieving respiratory distress.

“For those first seven months, the only relief I got was on my bike,” Wertkin said.

His condition slowly improved. Then came an upgrade—a Specialized Turbo Levo class 1 eMTB capable of handling real trails. But as Wertkin fell in love with mountain biking, his body fell apart. Even “turbo mode” on his new bike was becoming too difficult to handle. Complications led to the need for more risky surgeries to try and tighten down his ailing diaphragm. In December 2021, Wertkin was released from a New York hospital after a 23-day stint that left him completely ravaged, but alive. During the ordeal, doctors had at one point estimated a 20-percent chance of survival.

For Wertkin, 2022 was a year of reawakening. He’s now slowly easing back into work and continuing to build his strength. He’s savoring time with Ginnie Jo and their daughters. Last summer, he bought a traditional mountain bike to see how a lighter, more agile ride would feel. He logged five “analog” rides before the snow hit.

“I was euphoric on those rides,” he said.

His introduction to mountain biking hasn’t always been smooth sailing. He’s had riders yell at him—“e-bikes are for lazy people,” he was once told—even on trails that allow class 1 eMTBs with his ADA placard. Other times, Wertkin has noticed some mountain bikers will completely ignore him, as if pretending he’s not even there. As a result, he mostly rides alone.

“I understand the trepidation from old-school mountain bikers, and I get it, I mean I usually do double the miles,” Wertkin said. “But I try to be the absolute best bike citizen I can be.”

“I understand the trepidation from old-school mountain bikers, and I get it, I mean I usually do double the miles. But I try to be the absolute best bike citizen I can be.” — Sol Wertkin

In late November, Wertkin took off for a road trip to check out Utah and Arizona. As his local trails sat under a few feet of snow, he was antsy to keep pedaling. Cruising south in his ’91 Ford Okanagan camper van, he felt a tinge of nervousness. How would he be received on trails in a region unfamiliar to him?

Large governmental agencies are beginning to take notice of the uptick in new eMTB riders such as Wertkin. In December 2022, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) released findings from its own e-bike research study that aimed to catalog existing opportunities and challenges related to e-bikes. The study is the first to take a broad look at the available literature surrounding implications of e-bike recreation on public lands on a national scale in the U.S. It unearthed many questions with no available research: Are there differences in natural surface impacts between classes and types of e-bikes (Class 1, 2, or 3)? No research found. What factors do public land managers need to consider regarding the use of e-bikes on public lands while ensuring historical and cultural resource protection? No research found. How can existing trail infrastructure be adapted to accommodate a higher volume of users, and should it? No research found.

“New technology, features, formats, and marketing have contributed to an explosion in the popularity of e-bikes over the last several years,” the DOT report concluded. “E-bikes are here to stay.”

Wertkin is noticing hints of broader overall acceptance. Still, he pondered before his trip to the desert how he could avoid the negative interactions with other riders that he’d grown accustomed to. Ultimately, he arrived at a solution any mountain biker could be proud of.

“I’m going to bring both bikes, I think,” Wertkin said. “I have to make the best of the time I have.”

Read more about mountain biking's rise in popularity: