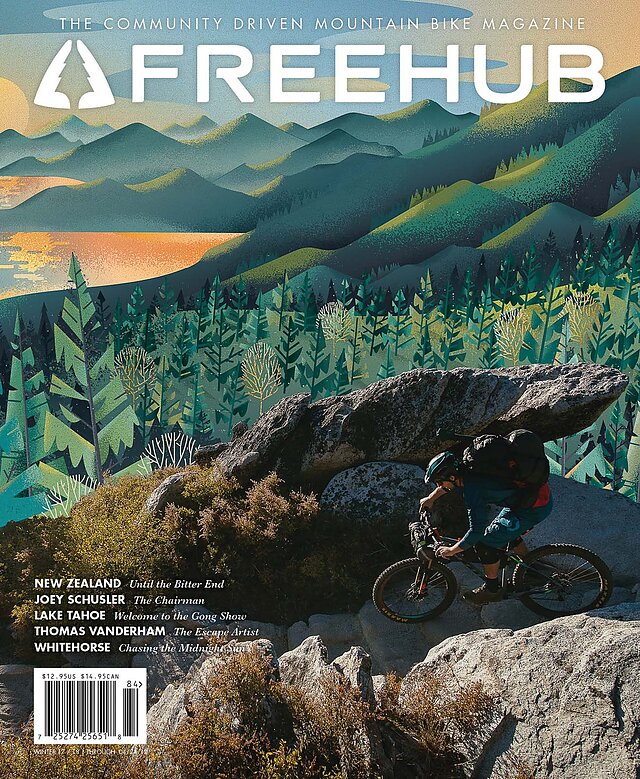

Welcome to Issue 8.4

True adventures always seem to start when plans go awry. In Issue 8.4, this means continually bump-starting a van in New Zealand, a quick visit to South Lake Tahoe’s Emergency Room, and in Canada’s Yukon, not knowing (or caring) what time of day it is. Adventure filmmaker Joey Schulser seeks new experiences on the far sides of the globe, while Thomas Vanderham reflects on where bikes have taken him, beyond geographical locations. Through everything, bikes serve as the impetus and provide a common denominator that transcends all languages and borders.

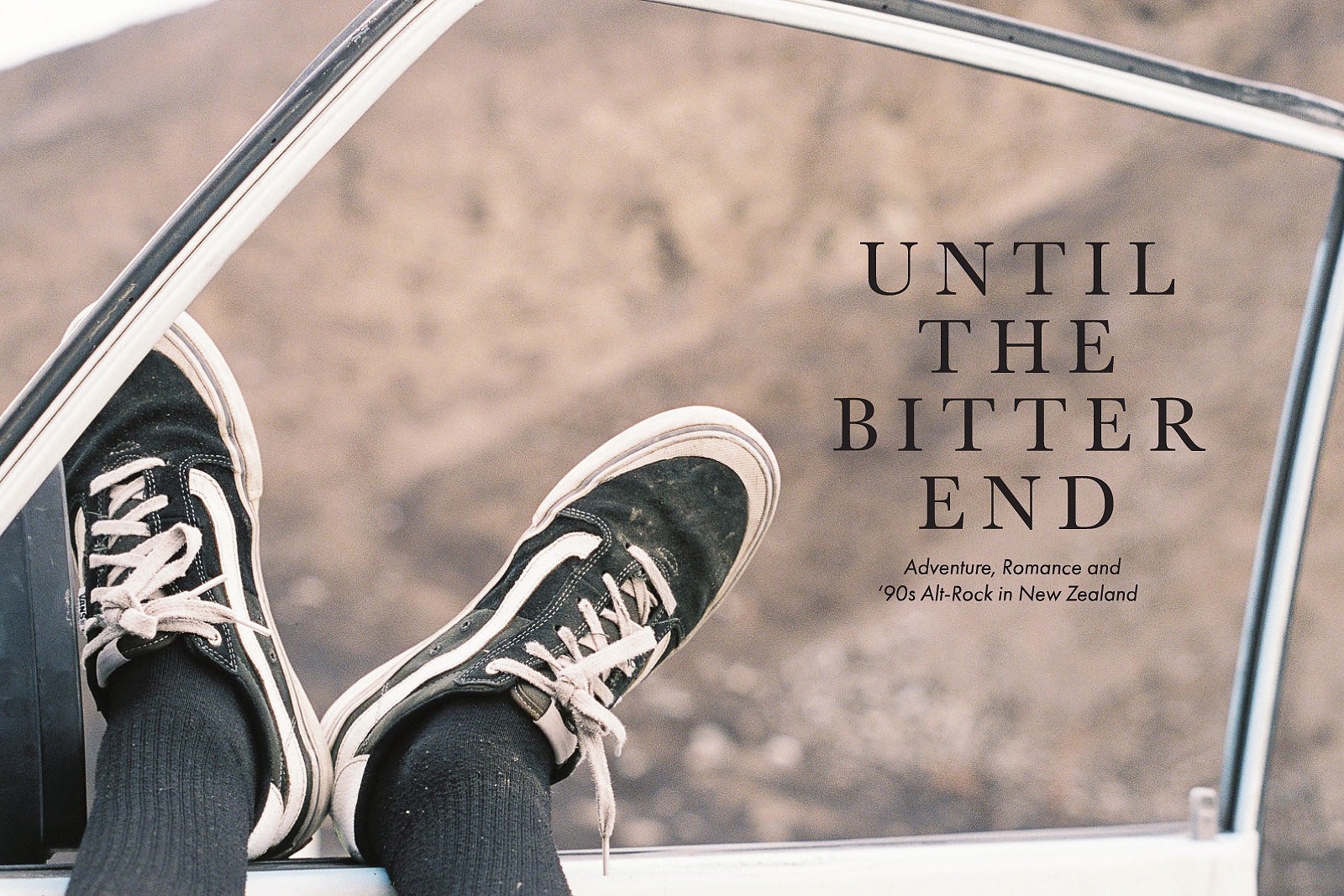

It’s an early April morning, and a touch of autumn is in the air as the two-liter, four-cylinder engine sputters to life.

The 1994 Ford Econovan, dubbed “Black Mamba,” pulls out of Christchurch, New Zealand, headed south along the coast toward the town of Dunedin. Like most vans in the country, the Mamba backfires as she makes her way down the two-lane highway, her rust-eaten chassis shaking with the potholes.

Inside are four smelly tourists, all on three-month visitor’s visas. Mark Taylor is at the wheel, talking Tinder and snacks, while Will Cadham gives him incorrect directions. Simon McLaine heckles both from a makeshift plywood bench in the back, while trying not to cough from a mix of exhaust fumes and dirty chamois odor.

I’m crammed in the middle, pointing my long-obsolete Super 8 camera out the Mamba’s equally abused windshield to capture, well, whatever we find ahead. Considering the past few weeks, that could include nearly anything.

This journey began at the end of January, when we left North America with intentions of racing in New Zealand for the 2017 winter season. To save money, the four of us decided to share expenses, buy a used van and make a documentary about privateer racing. But those plans began to unravel just a few days after arriving in Christchurch, when we learned there was a computer issue with the online lottery system. This meant if we wanted to compete in any of our scheduled races beyond the first two, we’d have to re-enter our names and hope we’d be selected by chance. We should have been anxious—those races were our reason for being in the country.

Words by Brian Haffner

Joey Schusler might be best known for making mountain bike adventure films, but his motion-picture career actually began with a saucer sled and a VHS camcorder when he was only 7 years old.

He and his longest-standing friend, Mason Lacy—whom he met on his first day of kindergarten—would while away winter afternoons in his Boulder, CO backyard, building snow ramps and sending it into the sunset.

At first it was just boys being boys, playing outside and conjuring up creative ways to raise the excitement level. But it didn’t take long for them to start documenting their antics, and by the third grade they’d already founded their own DIY operation, aptly named Complete Insanity Films.

“When we started, it was more about giving my dad the camcorder and doing stupid, ill-advisable stunts on sleds and bikes,” Schusler says. “We were pretty much just dicking around with it, and honestly it was less about the art of it and more about the stupidity of what we were doing.

“Then my parents got me this MiniDV camcorder and we upped our production game and started putting the Complete Insanity videos on YouTube. At one point, one of them got upward of 1.4 million views and we landed a sponsorship with a sled company. We couldn’t believe it. It got the wheels turning for what was possible.”

Words by Brice Minnigh

The face-plant comes out of nowhere.

Perhaps because I can barely see my front wheel over my handlebar bag, or maybe because gravity takes a quicker-than-usual pull on my unwisely heavy backpack. Either way, the ground seems to rush toward my face with unusual speed. I only have time to hope I don’t lose teeth before slamming into the dusty singletrack.

This bloody tumble may be particularly brutal, but we’ve been plagued by chaos since we started riding yesterday—45 minutes into our trip, to be exact, when Kevin’s derailleur exploded.

Despite its frustrating persistence, this logistical mess didn’t arise from lack of planning. Enduro racer and good friend Stan Jorgensen had been trying to put together a bike-packing and fly-fishing trip for the better part of a year. After thorough deliberation, several relocations and a late-summer shoulder blowout for Stan, we settled on a three-day adventure on California’s Tahoe Rim Trail in early October.

In its entirety, the Rim Trail completely circumnavigates Lake Tahoe, but a majority of the western portion is closed to bikes. We’d decided to ride the section connecting Mt. Rose Ski Area to Freel Peak, from which we’d drop into the small town of South Lake Tahoe. Along the way, we’d make stops at Marlette, Spooner and Star lakes, all with fish but only the latter two legally in season, ideally augmenting our other bare-bones rations with trout delicacies.

Words by Jann Eberharter | Photos by Margus Riga

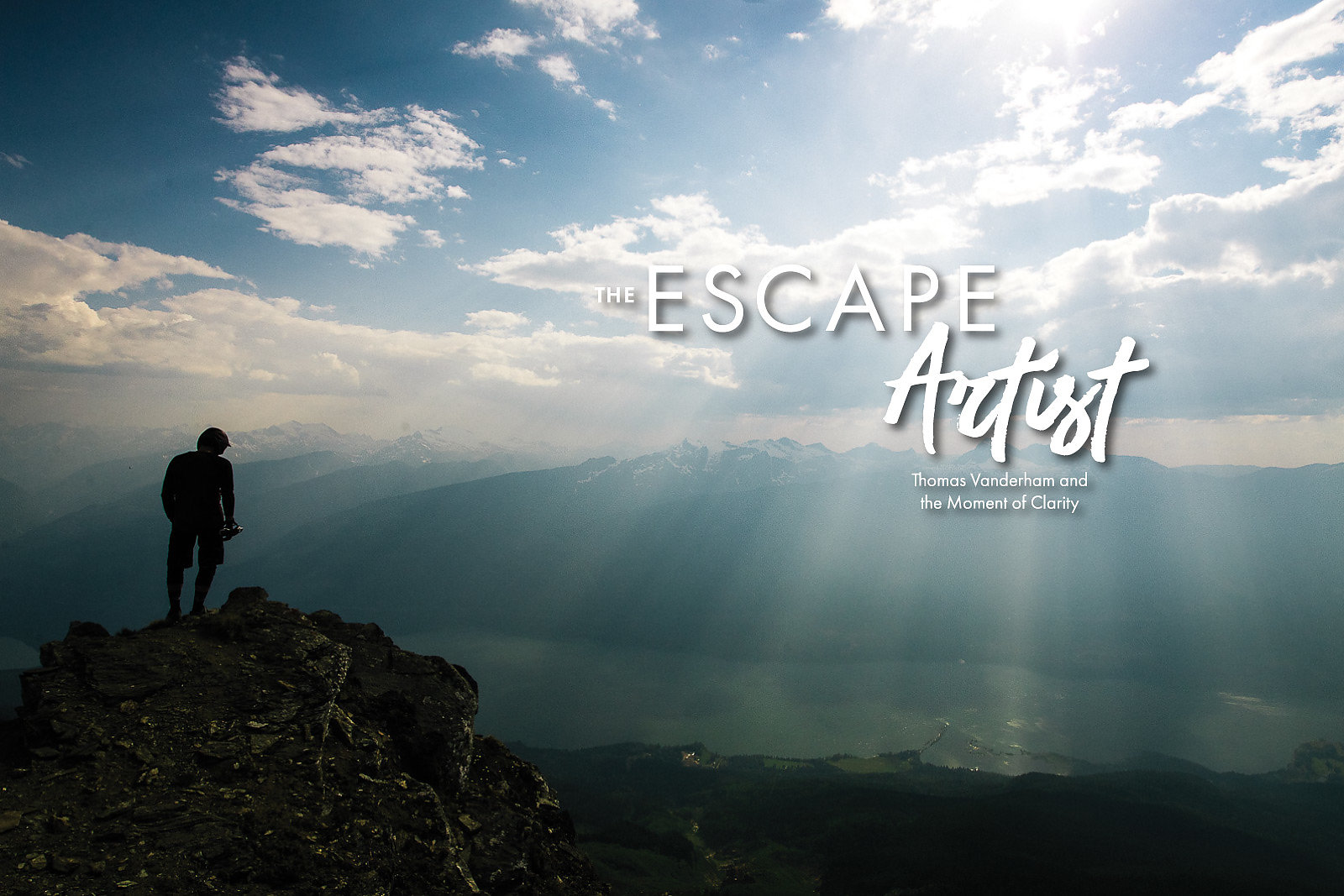

It can be tough to explain to a friend who doesn’t ride that mountain biking has healing properties.

I’ve tried. Most recently, it happened after returning home from a particularly memorable trip to Revelstoke, BC, when a buddy asked me how I could see something so painful as being therapeutic. Thinking about the high-alpine singletrack for which Revy is famous, it was obvious to me. I just couldn’t make it obvious to him. He laughed at my attempts, pointing out my scars, recalling my surgeries, and reminding me about all the dental work and trips to the emergency room.

The irony is not lost on me. Mountain biking has put my body through the wringer. But as I rode Revelstoke classics the previous week, my injuries never once entered my mind. In fact, over the years they have been powerful motivators to get back on my bike. It’s an existential concept that is hard to translate, but I’m always trying. The best way I’ve found is to tell a story, and that story starts with a feeling.

For some people, the feeling may have struck when they hit their first jump; for others, it may have started as early as the first ride without training wheels. Maybe it was overcoming a particularly brutal climb, or a post-shred beverage shared with good company. It is different for everybody, but I’m convinced that once we’ve felt it, we are constantly seeking to re-create it.

Words by Thomas Vanderham | Photos by Paris Gore

It’s stated on our tickets, but when the plane’s wheels touch down, there’s no way to tell what time it is.

It could be 7 a.m. Or it could be 7 p.m. That’s because during summer in Whitehorse, the capital of the Yukon, it’s sunny for 19 hours a day.

Located at 60 degrees north of the equator, summer light in the Yukon is nearly inescapable, especially during the solstice, which is just a few days off. This means seemingly endless sunsets and riding at any hour, but it also means time is irrelevant—at least as us southerners know it. And as Claire Buchar, Jaime Hill, Chris Grundberg and myself step off the plane to meet Dylan Sherrard, we’re still trying to figure out if that’s a good thing.

It’s not just a shocker for us. It’s also a homecoming for Whitehorse native Sherrard, who flew in a few days ago, and after years away he’s readapting to the strange, uniquely northerner schedule. He’s ready to show us the people and places of his youth, the unofficial training ground of trails, dirt jumps and gravel pits that would eventually earn him the nickname “Shred-Hard Sherrard.” But much has changed during his absence from the former Gold Rush supply town, so it’s also a chance for him to reconnect with—and rediscover—his hometown.

As the legendary writer of the North, Jack London, put it: “The proper function of man is to live, not exist. I shall not waste my days in trying to prolong them. I shall use my time.” In the land of the never-ending sun, where the days are already infinite, we’ll soon learn it’s almost impossible to do anything else.

Words and Photos Danielle Baker

It comes from my right, an explosion in the trail-side bushes that puts my heart into my throat.

I jump aside, and my surprise fades as a ruffled grouse, one of the many bird species native to the area, flutters off into safer foliage. I know the area’s only natural predator is a 10-pound wild cat, but when you’re someplace that feels this remote, it’s impossible for the imagination not to wander.

While the fauna isn’t dangerous, I’ve been well-warned that the weather is. I’m 15 minutes into my first ride in the Central Cairngorm Mountains, just five miles as the crow flies from the nearest village, and there’s no sign of civilization besides this narrow thread of singletrack, barely visible as it disappears into the scabrous, heather-clad mountains ahead.

My husband and I arrived in Scotland less than 24 hours before, on a self-guided mission to explore the network of trails outside the small town of Braemar. Home to just under 1,000 people and multiple castles, Braemar is located along the River Dee, in the craggy mountains of the Scottish Highlands. The peaks aren’t dramatic, but they are the tallest—and coldest—in Scotland, an area of stunning views with an ever-present frontier feel.

Words and Photos Leslie Kehmeier