When it comes to Idaho’s White Cloud Mountains, biking tends to involve hiking.

Back in 2014, we were midway through the Gem State’s renowned Castle Divide route, which begins near the town of Stanley and traverses through the heart of the Boulder and White Cloud mountain ranges. We weren’t riding. Rather, we were pushing our bikes toward the ridgeline far above.

In the White Clouds, however, the way down is always worth the climb. As we dropped through the 5,000-foot descent, we passed through every variety of Idaho mountain biking, from high alpine singletrack to dark trees, chundery stream crossings, open meadows and dusty sagebrush. We finished at the headwaters of the East Fork of the Salmon River, prime habitat for endangered bull trout and a great cool-off spot in the mid-summer heat...

Words: Tom Fynn | Photos: Leslie Kehmeier

Mountain bike racing is a hard, expensive and generally pointless endeavor.

It takes someone who is at least a little bit off to spend all their time, money and energy losing races that the vast majority of the population could not care less about.

As is the case with shared, unnecessary misery, racers tend to form uniquely tight bonds. All season, we pre-ride courses together, travel together between events, explore new towns and trails, and develop our own language of inside jokes in the process. We call each other “summer friends,” and once the season ends we return to our respective homes and jobs and keep a running dialogue via text message emojis and Instagram comments...

Words: Brian Haffner | Photos: Will Cadham

The line spills out onto the sidewalk from the old Victorian house, where the crowd’s excited conversations mesh into one jubilant, undecipherable hum.

It’s another Thursday evening in July, and a stack of bikes fill up the yard like skittle-colored dominos. The queue inches forward into the living room, where several dozen people mix mojitos before heading back outside. From a distance, it looks like as if a piece of Whistler invaded an idyllic small town from 1950s America.

But it isn’t the ‘50s, and we’re hundreds of miles from Whistler. The house sits on Second Street, in the British Columbian town of Revelstoke—population 7,200—and the crowd is made up of local mountain bikers. At the center is Brent Strand, a spry, silver-goateed man whose raspy tenor tells people to “drink up” as he counts attendees. The official total is 69, a new record including almost as many men as women. As the founder and organizer of the get-together, Strand is visibly thrilled...

Words: Matt Cote | Photos: Paris Gore

Brice Minnigh has a stamp collection. That’s how he ended up at a marionette show with Muhammed Ali, in the capital of North Korea.

It’s the kind of story that would be a highlight of most people’s lives. For Minnigh, it takes two hours of interview before he remembers a press trip he took to the country, while he was working for a government newspaper in Beijing.

“For a while I collected North Korean stamps, which have all this wild propaganda art on them,” Minnigh says. “There was a stamp shop in the hotel where we were staying, and as I walked in I saw Muhammed Ali in the foyer. I admire Muhammed Ali in a big way, and I stopped in my tracks and was like, ‘Champ!’ We talked, and next thing I was sitting next to Muhammed Ali at a North Korean puppet show.”

When you have as many stories as Minnigh, veteran journalist and longtime editor of BIKE Magazine, it’s not surprising you’ll forget a few...

Words: Sakeus Bankson

Māori legend has it that the demi-god Maui pulled a fish so big from the South Pacific Ocean it could feed his family for days.

It was so large, in fact, that the fish became more than a meal. It became the North Island of New Zealand.

But such a large catch caught the attention of both the gods and Maui’s greedy siblings. When Maui set off to placate the gods, his brothers dug in, carving the peaks and valleys that now cover the island. For his brothers, it was a display of selfish nature. But for the mountain bikers to come, it was an act of disobedience for which they would be eternally grateful.

Now the offenses of Maui’s brothers are marvels of nature, attracting tourists from around the world for their lonely beauty and vibrant greenery. Over the last three decades, they’ve also attracted multiple waves of mountain bikers, who would stay to make their own impacts on the land and culture...

Words: Jeff Carter | Photos: Sven Martin

The city of Roanoke’s water manager, Kit Kizer, had a trail named after him, and that was not a compliment.

He didn’t even like mountain bikers. Yet, on a summer day in 1997, he sat in a 4x4 beside two trail-poaching riders, taking a tour of the forest surrounding Virginia’s Carvins Cove.

The path to the 4x4 ride had been building for years. It started when Kizer opened the Cove’s reservoir to motorboats, but publicly denied mountain bike access. Feeling unjustifiably pushed out of the area, renegade riders snuck into the Cove throughout the 1990s to build trails with names like “Kit and Caboodle.” All the while, the Roanoke riders passed around hand drawn maps, relishing in the obscurity of their rides while also keeping lookout for Kizer’s enforcement crew.

Wes Best was one of the riders in the 4x4 with Kizer; he was also one of the renegades. That morning Best had swapped his Grateful Dead shirt for a bike jersey, preparing for the nervous drive with his adversary...

Words Kristian Jackson | Photos: Sam Dean

At first glance, they were just a bunch of punk kids from Vancouver, wearing bandanas, drinking 40s and riding mountain bikes around the city.

They caled themselves the Bicycle Rockers, and dropped into skate parks on their downhill rigs, built dirt jumps and sent huge stair sets. With their “we-don’t-take-shit-from-nobody” attitude and BMX tricks, the small crew was doing more than just pissing off the neighbors. They were introducing a punk mentality into the young and confined sport.

At the same time, in the early 2000s, the North Shore mountain bike scene was just starting to blow up. I was 10 or 12 years old, and every time my mom and I would visit the grocery store I’d beg her to buy the latest BIKE Magazine or that year’s North Shore Odyssey calendar. Then I’d go home and cut out my favorite shots, pasting them on the walls of my bedroom.

As the imagery spread onto my ceiling, I began to discover the different photographers and riders of the era. The sport was new, people were just starting to explore what was rideable, and I absorbed every bit of that progression as I possibly could. I was interested in photography myself, and I carefully noted the styles, subjects and locations favored by each shooter. And at the bottom of so many of those incredible photos was a small, scribbled signature: “Harookz”...

Words: Dylan Dunkerton | Photos: Haruki "Harookz" Noguchi

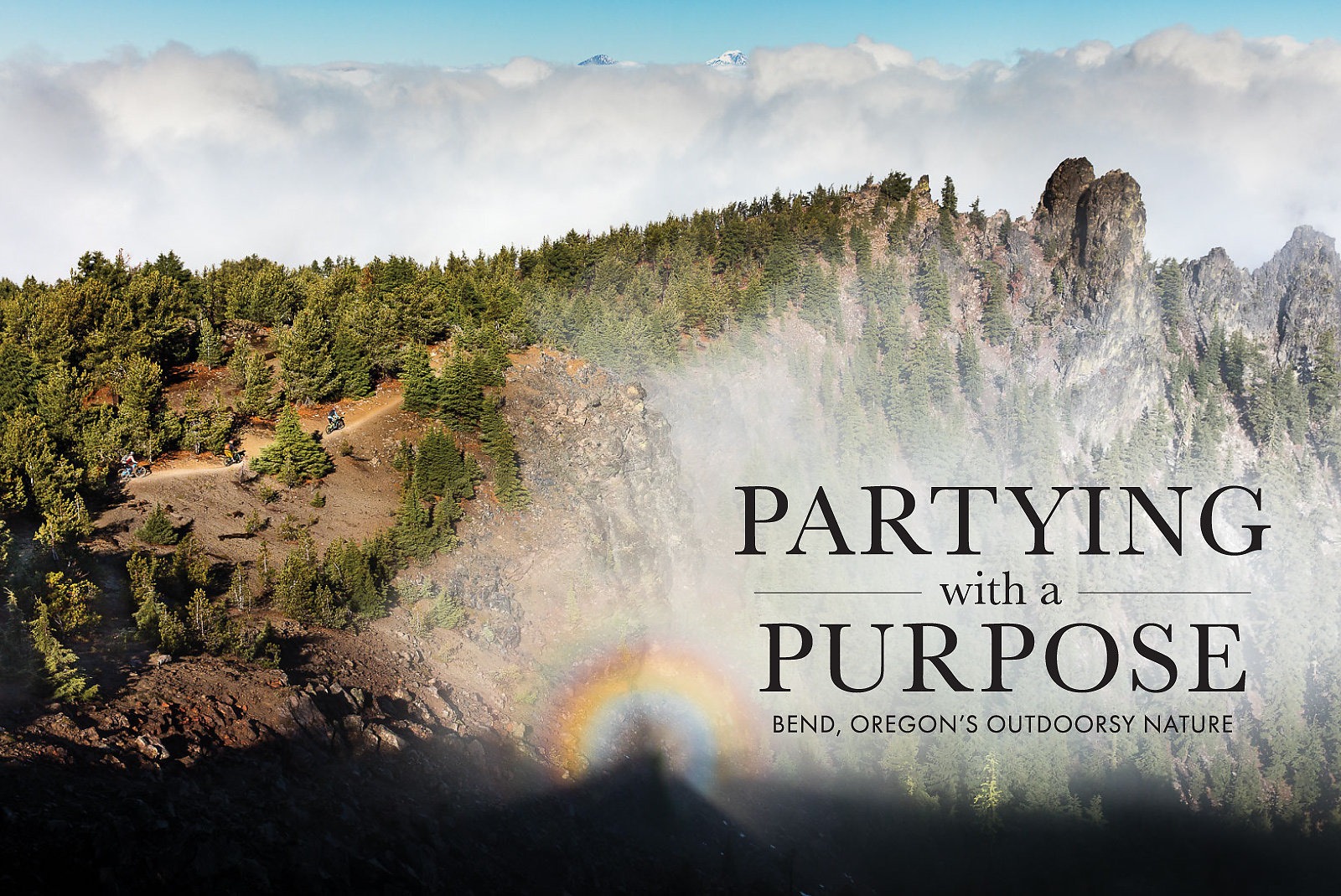

On the west side of Bend, a town of 80,000 people located in central Oregon, there is a neighborhood dubbed “Klister Corner.”

The name comes from a very messy XC ski wax, which for decades has been the subject of fiery and nerdy debates among area residents—and the glue holding the community together.

Then, in 1979, rumors of Marin’s off-road bicycling boom began arriving on the Corner. Like typical Bendites, the area residents were active and outdoorsy, and the fledgling sport found fertile cultural ground. Instead of paraffin, the resulting summer discussions soon centered around the value of V-brakes, or steel frames versus aluminum.

The debates were just as fiery and just as nerdy as in winter, and the participants’ dedication was just as passionate. Over the summer, a little fleet of klunker bikes began to appear in the Corner. The area had another advantage: a nearby prominence called Awbrey Butte was laced with old logging roads and game trails, and a small group began to assemble at the base for regular rides...

Words: Bob Woodward | Photos: Tyler Roemer

Cover photographer: Tyler Roemer