A Conscious Choice

There are two big disappointments in Adrian Marcoux’s world: how much electricity a toaster uses and the lack of a window over his sink.

Whether there is enough power for the appliance or warm water in the sink can depend on a number of things. It could be the temperature—at minus 4 degrees [Celcius] the water pipe feeding his miniature hydropower plant and house faucets will freeze, meaning no electricity and no running water. It could be leaves obscuring the intake spout on Skookum Creek. Or it could be the placement of a Troy Lee jersey stretched over a collection barrel as a silt deflector.

It seems that, as one of the best mountain bike photographers in the game, the hardest part of Adrian’s day would be creating stunning images for one of the most well-known bike brands in the world. Instead, for half of the year it’s keeping the water running and the lights on.

Adrian has been shooting with SRAM for more than a decade, and his images have become synonymous with the brand and its athletes—although you may not know that, as his self-promotion is as humble as his off-the-grid home outside of Squamish, BC. He spends most of his year on the road shooting and so has decided that time at home means slowing down the pace—although it doesn’t mean easing up on the hard work.

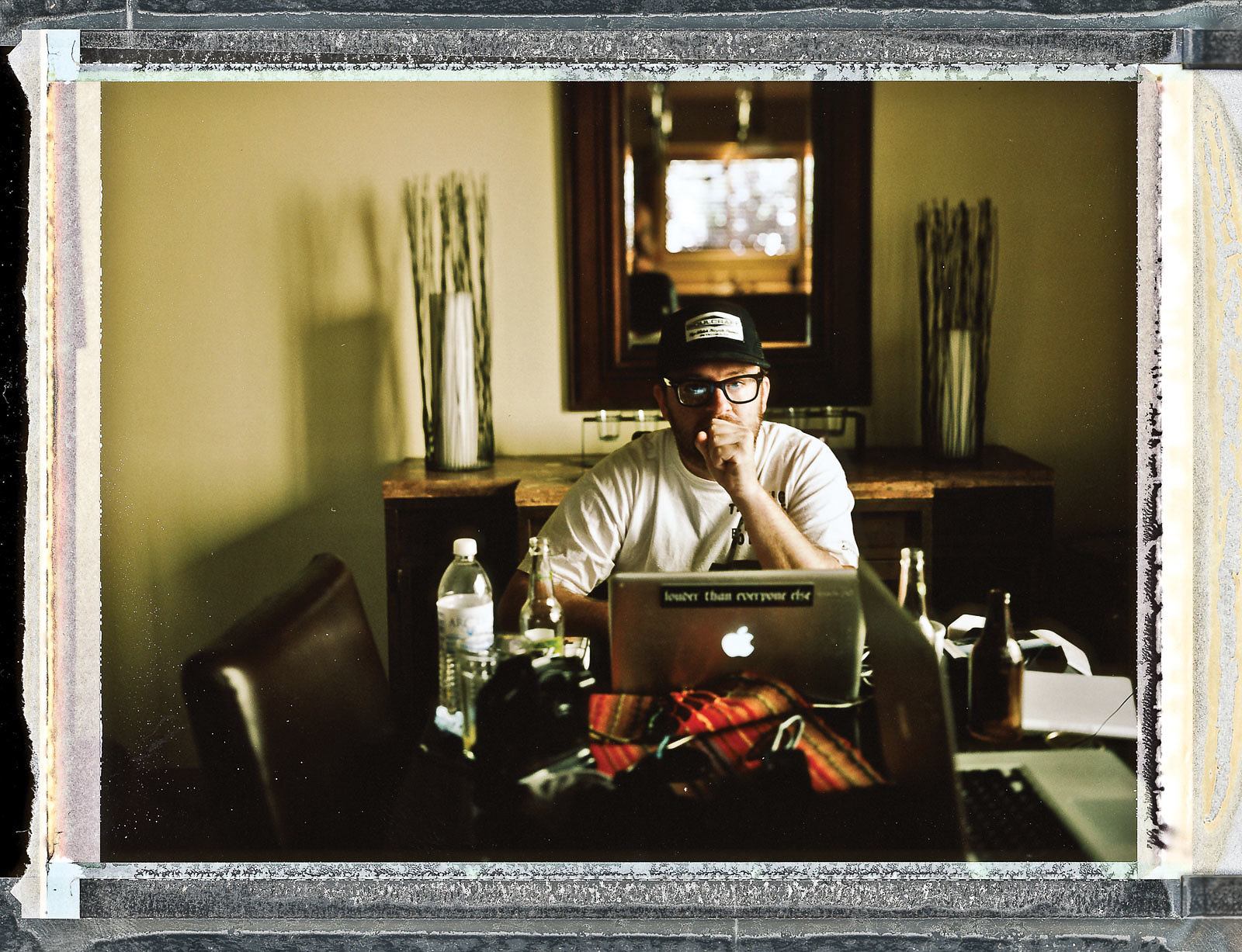

Right: The original caption for this image was printed in one of Adrian’s personal projects a few years back. Part of it read, “Everything I see, manifests itself into an initial gut impression and usually results in an image, one that I urge you, to take from it what you need.” Words of wisdom that have served Adrian well. Photo: Adrian Marcoux

Five years after buying his personal site of solitude, Adrian must still walk along Skookum Creek, which runs behind the house, to clear leaves, realign the intake spout, fix broken pipes and replace filters. As he does this, he shares his journey from rock-climbing tree planter to self-sufficient master documentarian with an authenticity rare in a world of sugarcoated social media and “Camp Vibes” marketing. He lacks the abrasive bravado of someone perpetuating a trend and instead speaks freely (sighing exhaustedly at times) about the trials and errors, successes and failures, of the life he has chosen.

And what a life it is.

“Anting around—that’s what my mom calls it,” Adrian explains while checking his water line up Skookum Creek.

It’s a term he uses to describe the constant motion of the daily chores and projects that keep his household running. Very few people, even the most avid outdoor enthusiasts, would choose a day of hard labor for enough power to cook a Pop Tart and hot water to wash the dishes. For Adrian, the choice is about balance, but it’s not one he arrived at entirely on purpose.

Adrian’s decision to pick up a camera was inspired by his father, who made a determined effort to document the family’s lives as they grew up. His journey into mountain biking was also an organic one. And while he rode bikes in his younger years, Adrian first started shooting climbing, a sport that “swallowed him up” and spit him out when he blew his knee.

After that Adrian drifted away from climbing, working on a tree-planting crew during the summers. It was an unlikely place to gain artistic inspiration, but one of his coworkers convinced him to start shooting again. Adrian planted long enough to save some money for college tuition. Then he headed to Victoria, BC, where he earned a degree in photography.

With his new credentials under his belt, Adrian set out to find home. He hit the road on a tour of small British Columbian mountain towns. “I just kept driving and stopped in Golden,” he says. “I ended up being there for 10 years.”

During the next few years, Adrian made ends meet by working in the northern oil fields, running a portable saw mill and wrenching on sleds in a shop. All the while he continued to hone his photography skills, shooting weddings and his friends hucking bikes off cliffs and jumps. His break came while he was shooting the infamous Mount 7 Psychosis downhill race in Golden, where he met SRAM Marketing Manager Tyler Morland. The two struck up a friendship, which led him to working with the company. Ten years later, if you see a SRAM brochure, ad or print project, most likely the photos were shot by Adrian.

Adrian may specialize in mountain biking, but his style seems more suited to documenting wars and revolutions. He constantly has his camera in hand, whether it’s in day-to-day life or at events like Rampage. The resulting photos have the feel of watching history in the making—not just flashy mountain bike images, but actual moments upon which the sport’s culture is built.

“I can’t set up a photo in a studio setting very well,” he says. “I can light it properly, but it’s not something I’m wired to do. I’m so much more into hanging out behind the scenes and documenting a moment as it happens. That’s what keeps me going.”

Despite his obvious talent, Adrian isn’t one to take credit loudly. Rather, he has maintained an obscurity that at times has left him with less recognition than he deserves. But that’s okay with Adrian; first and foremost he expresses his gratitude for his career, the depth of SRAM’s marketing campaigns, and their presentation of his photographs. According to Adrian, he just happens to be in the right place and around the right people.

“I managed to do it all from the shadows in a way,” he says. “I never really set things up. I just document things as they happened.”

“I managed to do it all from the shadows in a way,” he says. “I never really set things up. I just document things as they happened. So in reality, it would be those [athletes] who basically shaped the brand.”

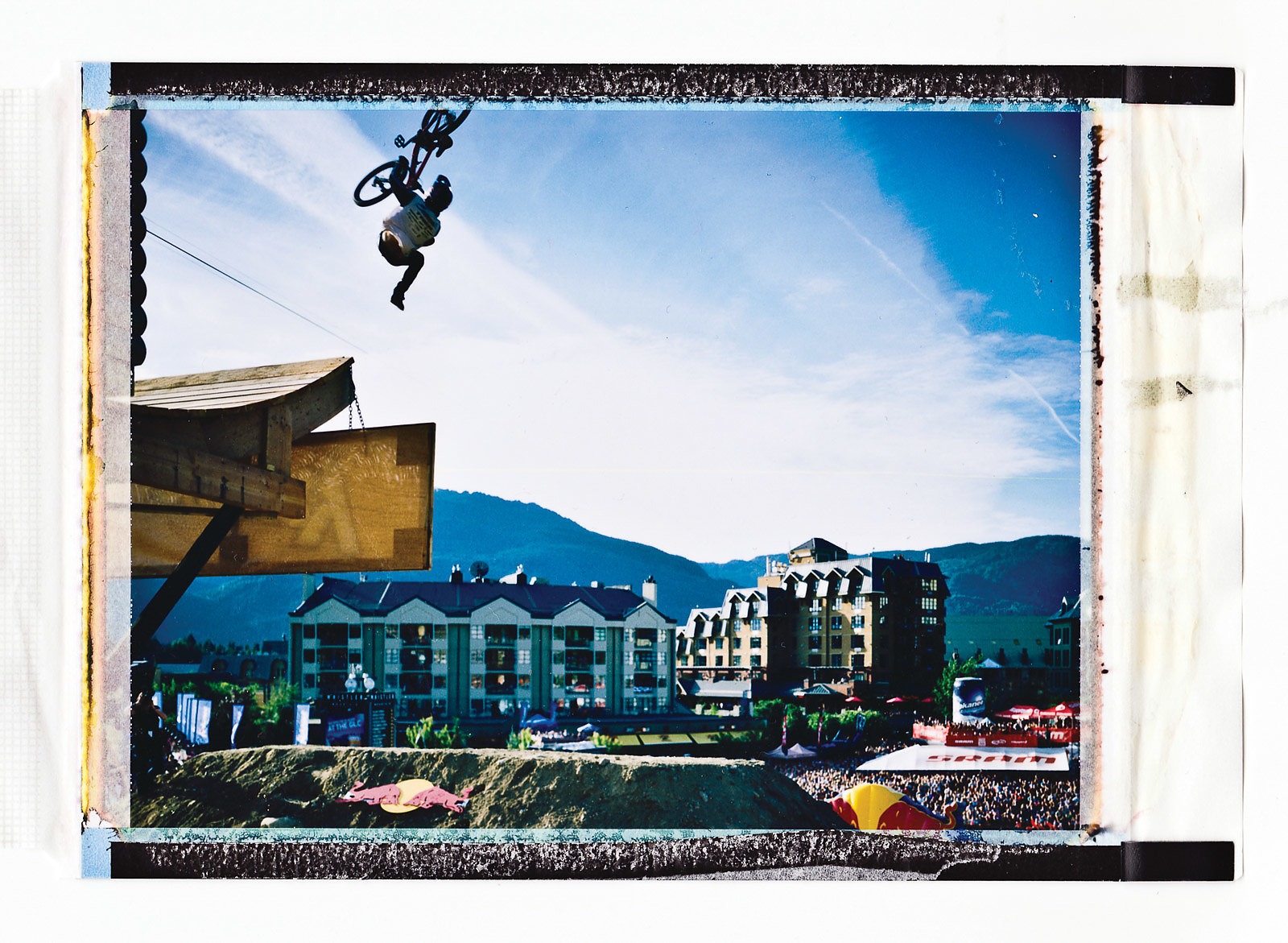

Three years ago at Crankworx, Adrian decided—despite vehement doubt from other photographers—to shoot Brandon Semenuk’s final Joyride run on a 4x5 camera with instant Fuji film. Such a setup requires a tripod and a whole different level of focus adjustments, light metering and exposure setting. And then once the single sheet of film is loaded, you’re shooting blind, meaning Adrian would get one shot and one shot only of SRAM’s top rider. The run ended up earning Semenuk another Joyride victory, and the resulting image ran as a celebratory double-page SRAM ad. “Those riders risk it, why can’t we sometimes?” he says.

Tucked up a logging road near Squamish, the back of Adrian’s property buts against a National Park and the front is lined by a thick barrier of trees. Considering his house is essentially hidden from even his like-minded neighbors, it’s ironic that Adrian’s move to the Squamish backwoods was intended to make the rest of the world more accessible.

In Golden, the closest international airport is three-and-a-half hours away, along roads that are often impassable due to winter storms. For a professional photographer whose work requires significant international travel, this is not the best situation. So five years ago Adrian decided to resettle along the Sea-to-Sky Highway, where year-round flights to anywhere are only two hours down the highway.

While his plan from the beginning was to live remotely and without support from municipal utilities, Adrian describes moving into his new home as a “rude awakening.” During the initial inspection, he was impressed by the marble floors and granite countertops in the kitchen, and was led to believe it had a working micro-hydro system sufficient to handle other “basic conveniences,” as stated in the real estate papers.

Upon arrival, he discovered the hydro setup actually only produced a trickle of power, and the previous owners had depended a great deal on a gasoline generator. Despite the flashy countertops and flooring, this equaled an unanticipated cost of roughly $300 a month. Along with no cell service, internet or cable TV, it was a rude awakening indeed.

“I was green and not afraid of figuring things out, but was definitely fooled by what the house looked like,” Adrian says. In addition to battling the elements for basic necessities, “it was fucking straight isolation.”

Still, this was his new home and he moved in during that first fall. It was sink or swim, and to get through the winter months he invested plenty of hard work and money to make the house liveable.

“I was green and not afraid of figuring things out, but was definitely fooled by what the house looked like.”

Now, half a decade after surviving that first winter, he still must walk the water line along Skookum Creek whenever he suspects problems with the micro hydro setup. It’s been a continual learning process. Over the first few winters, Adrian lost a number of intake systems while he was still getting to know the nature of the creek; they broke from the force of the water or simply washed away.

A short distance downstream is the open-topped collection barrel with the old Troy Lee jersey. The best solutions aren’t always the prettiest, and while it may seem MacGyvered, it’s the most efficient way he’s found to protect the expensive, easily damaged screens from silt. Inside his house is his tankless, in-line Paloma water heater, a finicky device that saves energy by providing water on demand, but whose trigger can also be easily fooled by sediment.

Cold winter temperatures, however, have become Adrian’s biggest adversary. The water pipe splits near the house with one section providing water to a tank on the hill behind it and the other running to the micro-hydro system. This means frozen pipes cut off the water to the house as well as the electricity.

“I’ve learned that the drinking water line freezes at minus 4 [Celsius],” Adrian says, “and so as soon as I see it’s going to reach minus 4, I make sure the tank is full. Then we’re good to go.”

He’s figured out a way to handle the temps on the plumbing line, using a low-voltage heating cable between the water tank and the house. The power line is a different battle. Being much longer than the plumbing, the heating cable doesn’t work and Adrian is left without power for the coldest weeks each winter. His current mission is finding a way to keep water from the creek flowing continuously downhill in order to avoid freezing points along the way.

And how does this constant list of domestic chores affect his riding? While on the road Adrian is always busy and surrounded by the bustling bike scene, and so when he returns to the woods, his solitary existence provides some balance to the madness.

“I ride by myself when I come home,” he says, “basically because I don’t want to ride with anyone else. I don’t want to chase people. I chase people for a living.”

If the demands on Adrian’s time from his career and keeping his home maintained aren’t enough, he creates extracurricular projects for himself as well. The most recent is his modded-out 1967 Land Rover Series IIA, which he spent two years building and has dubbed the “Grizzly Hunter.” It was a project of patience, and completing it forced him to give up his usual stubborn independence. He sought help from a local Squamish mechanic, and in the process “learned a lot about the rig and myself.”

Adrian can spend eight hours solving a small problem in the systems and trekking through the woods to remove leaves so he can flush the toilet that night. And that would be considered a big win. He comes home to a freezing-cold house and has to start a fire, not knowing if he’ll have hot water. He might have to turn the generator on or off, or haul gas if it’s run out.

It’s a tough existence, but one he’s consciously chosen and about which he has no complaints. As he describes each struggle, it may be in a tone of frustration or exhaustion, but there is also the pride and excitement about achievements and successes. He may have to tend his hot tub’s firebox for six hours, but the resulting soak with friends is even more enjoyable because of the effort. And when your biggest concern is the power your toaster requires, you must be doing something right.

“I’ve got a pretty good life,” Adrian says. “I don’t get bored because there’s always a shit ton to do. It’s not always meant to be an escape, but it’s quiet and nice to have people come share it—use the tub, ride some trails, get all fucking shitty and muddy and wash bikes, have a fire at night, and good food. That’s what it’s about.”